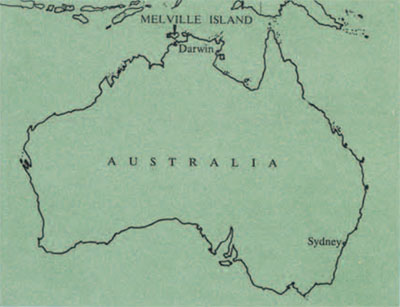

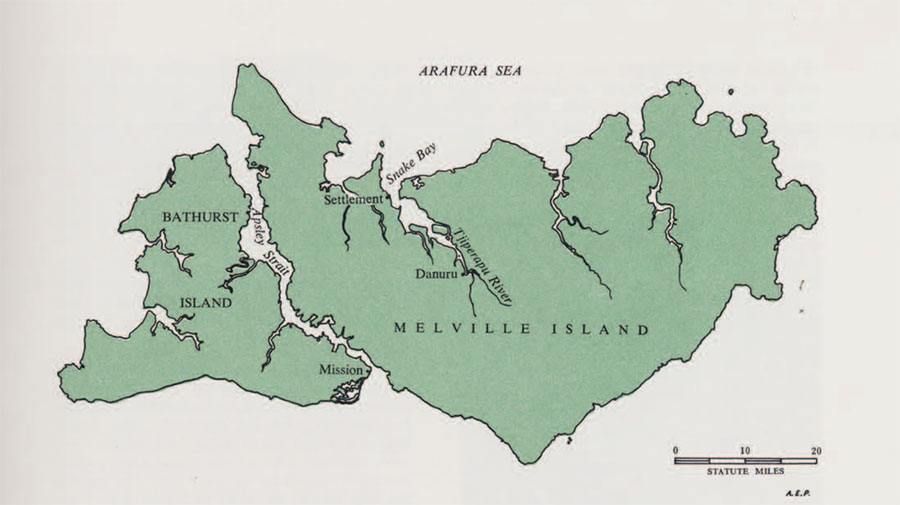

Readers of Miss Goodale’s account of Tiwi funeral ceremonies in the Fall 1959 number of EXPEDITION will remember that the Tiwi are one of the aboriginal tribes of Australia, and that a group of approximately 180 of them are living at the Australian Government Settlement at snake Bay on Melville Island, where they are learning to accept some Western ways while still retaining much of their Stone Age culture.

Miss Goodale lived among them from April to December 1954 and these sketches are based on happenings during those months. She has referred to her Tiwi friends by their English names because those are the names she always used in talking with them, but it should be remembered that while all of the children and some adults have been given English names by their white friends, every Tiwi is ritually given up to eighteen unique native names throughout his or her lifetime. While every native name must be unique, most of the English names are not, and thus distinctions are made in various ways. In the story, Dennis is a girl originally named Denise but never called that. Young Jenny is the youngest of five women of the same name–Long Jeanie, Jennie Green, Hoarse Jenny, Jeanie One and Two. And finally, as many native names are descriptive, so are a few of the English–one of these is Happy.

Dennis and Crissy-Boy

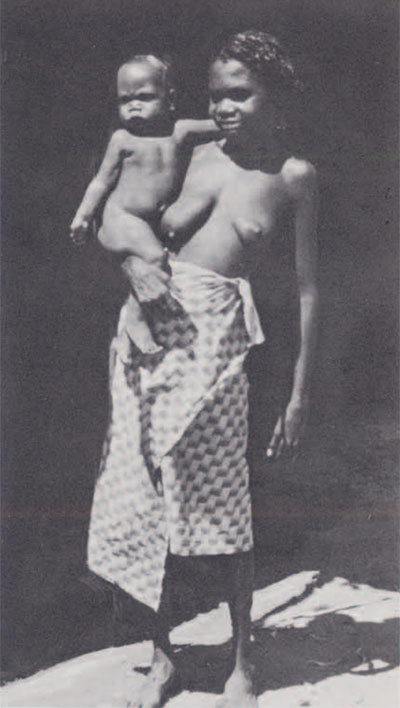

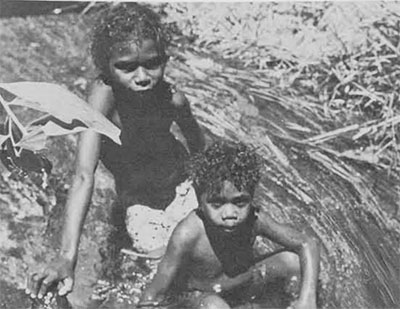

It is already a warm day and the air has a heavy content of moisture for the rainy season is not yet over even though it is mid-April. Fat Alice and her companions walk slowly through the bush, their naked feet treading carefully on the burned-over ground, their eyes constantly alert for the slithery movement of a poisonous snake. Dennis walks beside Fat Alice, her father’s sister. Behind the follow Margaret, Dennis’ mother, and her father’s second wife Filicy, with her small son Crissy-boy sitting on her shoulders, babbling cheerfully in neither Tiwi nor English but in his own childish language.

Each of the women carries a yam stick over her shoulder and a piece of calico or flour bag in one hand. Two of them have soot-blackened billy cans with their wire handles slung over the yam sticks, and as they walk, their movement causes some of the water in the cans to slosh out on the ground.

“We stop here,” announces Alice and places her billy can under the shade of a small macrazamia tree; and the other women put down their burdens and, in a quick movement, readjust their calico skirts by re-wrapping the strip of cloth around their waists. Crissy-Boy, having no clothes, goes skipping around but Dennis as a four-year old carefully imitates her elders and stretches her calico wide between her outstretched arms, then folds it over and tucks in the loose corner over her little hips.

A fire is made and the billy put on to boil for a cup of tea and the three women quickly dig up some small yams and put them in the fire to roast. Dennis and Crissy-Boy hover about the fire and as soon as a yam is cooked they receive it in their little outstretched hands and hungrily gobble the tasty morsel. The women content themselves with tea and shortly return to the main task of digging the yams.

Revived by their repast, the two children invent a game. Closing their eyes, they run about the small area with their arms raised high until one of them with squeals of surprise tumbles into one of the yam holes. Climbing out, they start again, their shrill voices growing louder as the game goes on. The women continue their work without a glance at the two youngsters.

Eventually tiring of this sport, Dennis begins gathering twigs and builds a small fire-pile in a clear spot on the ground. Imitating her, Crissy-Boy contributes two small twigs, then watches as Dennis carefully picks up a burning stick from the yam fire and carries it to her pile, laying it carefully on top of the twigs. Both children now lie flat on their stomachs and from opposite sides blow and blow upon their fire until they lie back coughing for breath, the immediate result of their efforts being an anaemic wisp of smoke struggling upwards. Recovering rapidly, the two children dart about gathering more sticks to place on the smoking pile in an attempt to coax a flame or two, but only succeed in extinguishing what life there was.

Now they are tired and their mothers have gathered many yams and call them to the shade and take them into their laps. Each child munches on a yam, and Crissy-Boy is given his mother’s breast to nurse for a few minutes until his eyes close and he is asleep. Dennis is not far behind and soon only the soft voices of the women break the warm hum of the afternoon.

Playing Grown Up

On the hill near his brush shade where he and his wife had lived until her death a few weeks ago, Jimmy waited for his deceased wife’s relatives to gather before he could begin the evening’s ilanea in her honor. It was a long wait for the goat herders had not yet arrived and these two women would be extremely angry if the dancing began without them. One of them in particular was already angry with the widower Jimmy because he had defied custom by usurping the leadership role in the funeral which rightfully belonged to his wife’s paternal kinsmen, of whom the goat herder was one.

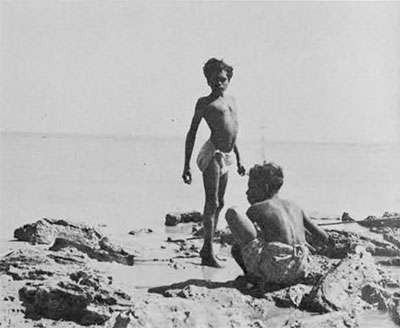

Jimmy was growing angry too, for all was not proceeding as he ordered and murmured criticism from assembled groups was reaching his ears. But before the tension reached a breaking point, the children took over.

Down on the field below the hill, a small group of young boys and girls sat in a circle chatting. Then from behind a clump of bushes another boy appeared and stood quietly. He was joined by an emissary from the “home” group who whispered a name in his ear. The visiting boy returned to the bushes but soon emerged followed by his mob of boys and girls and all of them rushed to the “home” group, and flinging their arms about an opposing child, they wailed and sobbed in the most heartrending manner–for a minute or two. Then breaking away, the groups changed places, the grief changing abruptly to joy and laughter as they reformed, the “home” group inventing a death in their company to whisper to the “visiting” group when they should appear from the bushes, wailing and sobbing when the news was delivered.

The parents and relatives on the hill were amused and entertained by their children’s performance and speculated among themselves as to who might have been chosen for death each time the game began.

After a number of these preliminary rounds, one ten-year-old boy began to clap his hands together and the gang all gathered in a circle, the boys slapping their hands against their thighs in a fast beat. One little boy, not yet six, stamped into the center of the circle with his arms held straight above his head and danced his version of his father’s difficult shark dance, while the girls danced as a shuffling chorus on one side of the circle. Two brothers took over from the small boy and this time they were joined by their young sister and all three circled the ring, stamping the ground in time to the beat,

The children were quite serious now and the only signs of amusement came from their adult audience, who were careful to keep their comments low so they would not be overheard by the children. The “play ilanea” was soon broken up by the lead goat who wandered into their midst; and the shrill cries of the two goat women urging their reluctant charges homeward were the signal for the adults to take over and begin the serious work of the evening dance.

The Pandanus War

In the dusk of the evening, Stewart practiced his aim. He held a long pandanus frond in his hand and carefully crept up to the fire where his sister Blanchy played with a baby wallaby. His sister did not hear him approach and continued to set her newly orphaned pet some distance from her and try to coax it to come back hopping to her lap. But Stewart had a different plan and stood very quietly behind Blanchy. When the little wallaby turned to hop back, the pandanus spear was set quivering and then thrown at point blank range at its small quarry. The flexible missile flopped harmlessly to one side of the little animal who, in one leap, reached safety in the little girl’s arms. Blanchy rose to defend her new playmate and told her older brother in no uncertain terms to go find some other game and leave “joey” alone.

Steward was a nice little ten-year-old and he also knew his sister would give him no further chances for a sneak attack, so he picked up his “spear” and continued his practice with a dead stump for a target. But Stewart was foolhardy and did not keep an eye on his mischievous six-year-old sister. Quietly Blanchy rose and gave her pet to one of the women to keep and took her older sister’s little two-year-old daughter Patricia by the hand, and together they disappeared into the bush. They armed themselves with several pandanus frond spears and then, ever so carefully, they prepared their revenge attack. Approaching Stewart from opposite sides, they took up their positions unnoticed only a yard away from their enemy. Blanchy gave the signal, an ear splitting shriek, and they sent their spears wabbling through the air toward their mark. Completely surprised, Stewart froze momentarily, then ran toward a pandanus bush and gathered his ammunition, and the battle began.

The odds were about even to begin with, for little Patricia added little but vocal and moral support, and although Blanchy’s aim was not as good as her brother’s, she made up for it by being quicker on her feet, and easily dodged his spears. But Stewart was bigger and stronger, and faster at gathering and throwing the pandanus spears, and soon it was apparent that he had the upper hand. At this point, Patrick, Patricia’s father and Blanchy’s husband-to-be, entered the war on the side of his women-folk. Stewart, far from thinking this rather unfair, viewed Patrick as a worthy opponent and a great challenge; and the fighting continued with pandanus flying through the air almost continuously. The two little girls relinquished their aggressive role and became spear retrievers, scuttling underneath the barrage to gather the fallen ammunition and indiscriminately rearming both opponents.

Fortunately for Stewart, darkness enforced an indecisive peace and the young warriors returned to their camp fires quite ready to retire for the night, exhausted but happy. Blanchy curled up on the ground beside her brother and made a nest for the little wallaby in her arms. Before falling asleep, they sang a new school song, to the tune of the Volga Boatmen:

“Row, boys, row. Row, boys, row.

Bend your shoulders; row, boys, row.

Row, boys, row. Row, boys, row.

Bend your shoulders; row, boys, row.

Though the tide is free and fast,

We shall reach our goal at last.

The day is ending; soon night will fall.

Toil and labor, one and all.”

Happy Hunting

As I lie on my soft mattress of paperbark, snug under my mosquito net from the torments of the night, and warmed by the nearness of a small fire, I look over to the right where my three companions of the past days lie asleep–their forms outlined by the flickering light of four surrounding fires, and wonder about Happy.

Happy was one of my first Island friends. Soon after my arrival at Snake Bay, I had given a group of young boys and girls some lengths of string for it was my intention to record Melville Island string games or “cats’ cradles.” With hands quicker than the eye, the children formed a variety of figures and then explained what they represented and went on to tell stories concerning the depicted animal or spirit. Soon however, they stopped and one said to me, “If you really want figures and stories, ask Happy for she knows more than any one of us.” Soon I met Happy, a tall girl with a constant wide smile and merry eyes. As her slender body showed no signs of budding womanhood, I estimated her to be about eleven years old.

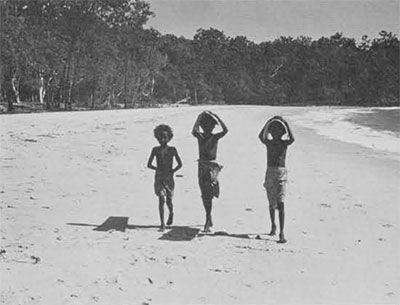

About a month after this, we decided to obtain some examples of the old-style water containers made from the leaf sheaths of the tall cabbage palm known locally as tulini. The nearest stand of these trees was up near the headwaters of the Tjiperapu River, a two-day journey. Happy’s parents, Laury and Nora, were asked to make this journey and to take me along. The first night we camped on the opposite shore of Snake Bay, for we had made too late a start to gain any distance up the mangrove-lined river where camping spots are rare. Laury and Nora were shy with me for I had, up to this time, spoken no more than greetings to them, but with Happy there was no strangeness and she took it upon herself to watch over and entertain me.

That first night after completing our simple meal, Happy and I went down to the water and sat on the beach, and she started to tell me about other trips she had made about the Island. With a stick she drew a map of the entire coastline of Melville Island and then began naming the points of land, the rivers and creeks, and the camping places, as she travelled with her finger over the hundreds of miles of shoreline circumnavigating the large island which was her home. Nora silently joined us and once or twice gave a forgotten name or corrected her daughter, but mistakes were few and the recital took close to an hour, for there were remembered events connected with many of the names.

Early the following morning, we set off in the large dugout canoe. Laury and Nora paddled steadily upriver while, from time to time, Happy dipped her own child-sized ironwood paddle into the water contributing her small power to the whole. At midday, we made landing on a small rocky beach and, without a word, Happy took the axe and began cutting into the tangled roots of the surrounding mangrove, pulling out the slimy mangrove worms and slipping them down her throat, while Nora built the fire and set the billy to boil, and I laid out the lunch of cheese and corned beef, of which we all partook as soon as the thick black tea was hot.

All afternoon we made our way up the quiet river, the banks closing in rapidly as we neared the end, and the light becoming tinged with green as the mangrove trees growing on each bank joined their branches overhead, making a complete archway. Colorful parakeets flitted through the leaves, catching occasional rays of sunlight and thereby gaining brilliance.

Rounding a bend, we made for the landing–a steep dry bank void of any mangroves. This landing had a name, Danuru, meaning “dry landing” for it was the only good landing for miles of river. There was also a camp–a collection of old bark lean-tos resting crookedly on sapling supports. Our belongings unloaded and the canoe secured with a large rock anchor, Happy was given our several billy cans and sent to collect fresh water from a neighboring billabong, while her father, with the axe over one shoulder, disappeared into the bush behind the camp in search of supper. The water chore completed, my young friend set to work on the lean-tos, taking a strip of bark from this one, a support from that one, and working industriously, singing all the while a medley of Tiwi love songs and “The old gray mare, he ain’t what he usta be.”

Finally she sat down beside me and pronounced her “shade” finished. “You sleep there tonight?” I inquired. “Oh no. That just for fun. I sleep outside.”

As the light began to fade, the evening chores began. There was firewood to collect–slow-burning wood for the night sleeping fires, and fast-burning wood for the cook fire. Again, Happy was sent out to collect both varieties and soon returned with all she could carry, which was quite enough for our purposes. The cooking fire was started by Nora and soon Laury appeared with two ‘possums, already gutted, which he handed to his wife, following the custom that “he who catches must not cook” (the first law of food distribution–for the cook gets a certain portion, the hunter another, while the rest is shared by companions). The ‘possums were soon cooked and with some additions from our dull selection of canned food and the inevitable tea, we dined. While there was still some light, Laury took the axe to the billabong and cut a large supply of supple paperbark for our beds, while Nora chased the snakes away from our camp by setting the surrounding bush on fire with a burning stick. The flames roared upwards and sped through the dry grass and dead fronds of pandanus, but soon the evening dew would fall and extinguish the flames;–the snakes presumable would not venture back over the burned ground till daylight.

Early the next morning we set out for the inland stand of tulini palms, hunting and burning the grass as we moved through the bush. Only two stops were made, one for a ‘possum and one for a nest of wild honey, but Laury marked in his mind likely ‘possum trees to be looked into on the journey back. After a few hours, we reached the open grassy area with the tall tulini palms standing majestically silhouetted against the deep blue sky. While Laury and Nora (and I) had a smoke, Happy chopped down a young tulini and cut open the very top of the trunk to reach the heart where the fibers were crisp and tender. It did not take the four of us long to finish this delicacy. Nora chopped the next one down, a larger, full grown tree, and this completed our lunch. We gathered half a dozen of the dry leaf-sheaths and began our journey back.

We were not hunting in earnest. Our progress was slower than usual because Happy was often instructed to climb a tree suspected of harboring a ‘possum; to test this, she inserted a stick into the hole and twisted it to pick up hairs from the quarry’s coat. If the test was successful, Laury took over and chopped or smoked the animal out of its home. It was almost dark when we returned to Danuru with two additional’possums. Again Happy was sent for water and firewood, and Nora prepared our supper while Laury attempted to patch some of the more obvious tears in the calico-and-flour-bag sail, for with the prevailing wind and current behind us, we would sail down the Tjiperapu to Snake Bay in the morning.

Why am I wondering about Happy as I know lie awake at Fanuru? From previous companionship with this eleven-year-old, I had grown to appreciate her knowledge of Tiwi legend which far surpassed that of the other children her age. On this trip I had observed the extent of her knowledge of the country, not only that portion with which she is personally familiar but her awareness of the entire Island, its size and shape, its names and much of its history. And in a more important aspect she had shown me that she knew the products of the country and how to obtain and utilize them to their best advantage. This in itself was not surprising, for had not Western influences come to her country, she would now be a married woman, expected to participate in the daily economic affairs of her husband’s household, and it was the duty of her parents to educate her in these and other aspects of Tiwi culture until she reached approximately eight or ten years of age. Happy’s parents had not given her to her promised husband a few years back when they should have. In this respect they had yielded to Western influence; but they had not stinted on her primary bush education. Tomorrow, however, Happy’s life would take a momentous turn. The supply ship from Darwin had been expected the day we left Snake Bay. On this ship, in addition to the usual cargo, were to be books, desks, chairs, and blackboards to fill the new and shiny but empty schoolhouse, and most important of all, on this boat would be the “Teacher,” an unknown element to be added to the small Settlement society.

I lie here thinking–trying to visualize the impact of this one man and his books on the future of Happy and her generation–I fall asleep.

Young Jenny

By any standards, Jenny was a beautiful young girl. Her slightly wavy, light brown hair with its red highlights framed the smooth-complexioned brown face in which were set twinkling black eyes, well-formed nose, merry mouth which almost never closed to hide her brilliantly white and even teeth. Her body was firm and well shaped, her hands delicater with long, tapering fingers and nails short and clean. Wearing only a naga, she had the appearance of a carefully groomed young lady. Her speech was quiet and modulated and her pleasant personality gained her many friends and often won her the leadership in activities undertaken with her contemporaries.

But of all her age group, Jenny had the most immediate and personal problems, for in 1954 she was caught right in the middle of the old and the new way of life. Jenny grew up in a household dominated by her mother, the second of four children. First came Margaret, now in her late ‘teens, then Jenny herself just entering her ‘teens, and Stewart about ten, and last, Blanch aged six. Their mother, in her thirties, was a firm disciplinarian and adhered strictly to the traditional ways of life. She not only insisted that her family conform to the time-tested customs, but was also consistently vocal in her criticism of others in the Settlement who strayed from the past ways. Many years ago, when she herself became a muringaletta upon reaching puberty, her own father had promised that her first female child would belong to a young man, Patrick, when she should reach the age of eight or ten. And so in due time, Margaret had been born and reared and given to Patrick, then in his thirties, as first wife. Jenny too had been promised to Patrick before she was born and she, in time, joined her older sister as second wife to a man almost thirty years her senior.

Very soon Jenny would reach puberty, and it had been planned to take her then into the bush for five days where she would stay with her parents and siblings, including Margaret, her co-wife. There her father would take a long wooden spear carved with many barbs on two sides and place it between his daughter’s legs, then give it to a man in the Settlement as a promise that Jenny’s first-born daughter would be given to him in exchange for the spear if he fulfilled his obligations to Jenny properly as a son-in-law should from this time on.

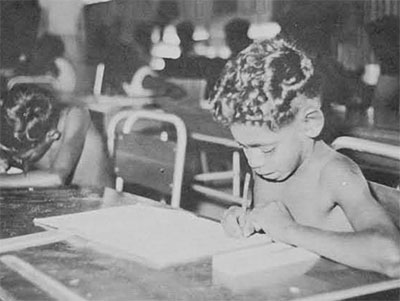

But other plans had been made, plans which might well change this course of events for Jenny and her future daughters. She had been married to a man who was not so unbending to the changing times as his parents-in-law. Patrick quite willingly acquiesced to government authority and sent his school-aged wife to school as soon as it began at the Settlement. Here, in the company of her generation, she passed the day in the happy discovery of new words to be read and written, songs to sing in part harmony, new games to play, and new manners to practice with one’s schoolmates. She owned her own school dress, her own pencil and notebook in which she recorded the events of the day gone by, illustrated in her own fashion. At recess she played soccer with the others or vented her energies with a skip-rope. She ate her lunch with the other children with a knife and fork, sitting at a long table.

However, with the close of the school day, when the other children took off to go swimming, or to wander through the bush in search of food and adventure, Jenny was torn between her desires and her duty. It was her duty to return to her husband’s camp and help her sister who was pregnant by taking care of that bundle of two-year-old energy that was Patricia, Margaret’s first-born. She had also to draw water and gather firewood before it grew dark. Patrick recognized his younger wife’s problems, but he also had his duty to train her to be a good wife and mother. More often than not, he would look the other way when Jenny delayed her return for several hours after school, but Jenny learned that there was a limit to his indulgence if she delayed too often or too long.

Patrick wished to maintain his authority over Jenny for reasons she did not quite understand. If Patrick had given up his young wife fully, she would have returned to her parents’ household, and he did not trust his mother-in-law to help and direct her through this critical period of change from the old pattern of life to the new. Patrick’s plans for Jenny included as much schooling as possible and then a new marriage to a person of her own choice, a form of marriage which her mother did not approve for it lessened the obligations of the son-in-law to her and reduced her sphere of influence. But Patrick was Jenny’s husband and as such had first say in her future and could thus overrule her mother. And so he would not free Jenny, who would remain the youngest wife in the Settlement and the only actually married girl in the school until such time as she would fall in love, when she would gain her freedom from the old ways.