Frit, the word derived from the Italian “fritta,” (fried), is a chemical compound made up of silicate of lime and copper that when fired in a furnace hardens into a crystalline material resembling faience. Used in numerous ancient civilizations, small frit objects were dispersed over great areas. Frit was probably the outcome of a glaze, and glassy frit glazes are known in Mesopotamia as early as the fourth millennium B.C. Whether by accident or not, the glazes, with attractive polished surfaces, were produced to make beads, inlay, and jewelry.

Elaborate texts in cuneiform have given a clue to ancient methods of manufacture, such as a tablet in the British Museum from the Royal Library at Nineveh, which includes recipes for simple uncolored frit, blue frit, and Egyptian Blue glass or faience. In all cases, the ingredients are mixed in a crucible, put down into a furnace, where a good smokeless fire burns, until the mixture reaches a white heat and is removed and let cool. The result of this is recrushed, put again into a cool furnace, heated until the mixture liquefies and can be poured into moulds. The furnace, fired by logs, produced high heats that rose between the “eyes” of the furnace.

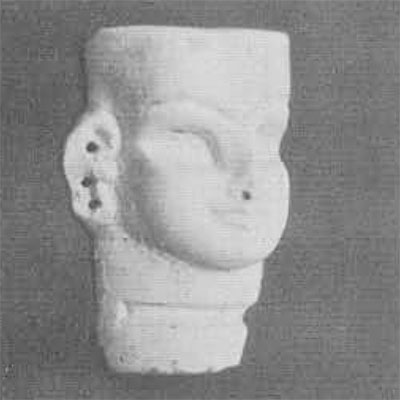

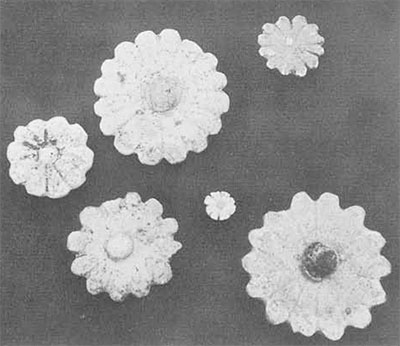

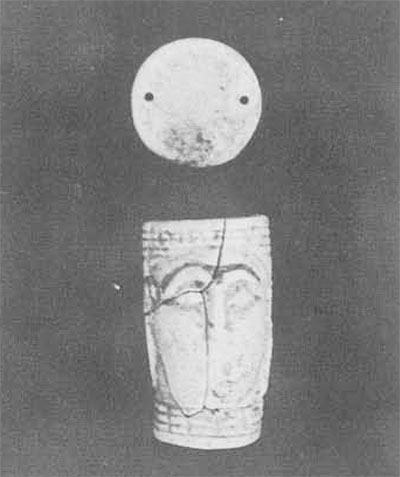

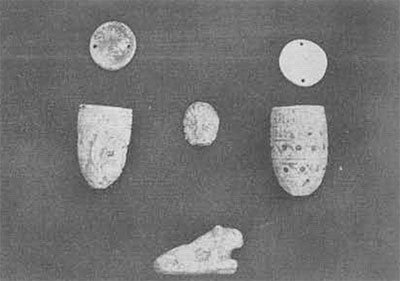

At Tell al-Rimah, in Northern Iraq, a large hoard of frit objects came to light during the first season’s work. Many of these objects, ranging from over a thousand beads of a variety of types, to cylinder seals, to miniature cosmetic capsules, to masks and amulets, were concentrated in the fill in front of the Temple facade and on the floor of a small room on the second level of the Ziggurat mound.

This room, located quite near the front terrace of the latest temple restoration, formed part of a complex of rooms built up on and served by a paved street in the Temple courtyard. In the damaged mud-brick room, the frit and glass objects predominated, having fallen in layers as if from shelves, while shells of various kinds and three or four small bone carvings were mixed in. At the end of the first season’s diggings at Tell al-Rimah, there was no evidence of a furnace being located nearby.

The concentration of the material, the number of beads and amulets and figured objects–faces and female nudes might easily be described as the goddess Ishtar–suggest a souvenir shop. If you go to any religious shrine today, even Chartres or the Vatican itself, a shop retailing religious objects is located within easy access to the basilica or cathedral. If at Tell al-Rimah we have a Temple of Ishtar–and a future season will determine this fact–why may we not have a religious article shop for the use of the visitors to a large religions shrine in the second millennium before Christ?