What did he doe with her brest-bone? He made him a violl to play thereupon.

What did he doe with her fingers so small?

He made him pegs to his violl withal!.

What did he doe with her nose-ridge?

Unto his violl he made him a bridge.

“The Twa Sisters,” a British Traditional Ballad.

A technological society defines most inventions, most devices, in terms of their supposed primary function as tools. Thus, a car is seen consciously mainly as a useful device for transporting us across the town or the country; its product, we believe, is transportation; and we have the greatest difficulty in understanding its other symbolic, psychological, and historical roots and functions. And yet, obviously, the automobile, in its design, appearance, wastefulness, illusory power, and indulgence of our restlessness lays bare the very heart of our society—its fantasies, its hidden preoccupation, its dreams.

Similarly, a musical to us is a tool made to produce musical sound, and the “better” the sound quality, the more highly we rate the instrument. We admire workmanship and “decoration,” of course, and we readily admit that the rich woods and complex shapes of instruments are beautiful, but our conscious thoughts, shaped by the bias of technology and functionalism, dwell but little on the form of an instrument. It was not always so; it is not everywhere so; indeed, it is not so in the deepest sense even for us.

All over the world—in legend, in shape, in lore, in nomenclature—there is evidence that musical instruments are not only (or even primarily) technological devices that are made only—mainly—for sound-production. Indeed it may be the other way round: a society, using whatever natural materials and constructional techniques are available, shapes instruments after its own symbolic preoccupations. The sound quality is but a result of this process. Instruments, and indeed the very music that they make, touch deep, strong roots in humankind. We need not look far to find stories describing the magical origin of music—and we need not look for these only in societies separated from us by thousands of years or thousands of miles. This theme occurs often in Irish and Scottish tradition, as is demonstrable in the following tale:

In the course of a banquet given at Dun-vegan Castle in Scotland, the Lord suggested a competition in which all pipers present would participate. Piper after piper took his turn, but when at last it came the turn of the local resident piper, MacCrimmon, it turned out that he was drunk—hopelessly drunk. Thereupon the chief insisted that a young and unskilled boy take MacCrimmon’s place. In despair, the lad rushed out and flung himself on a hillside, weeping bitterly. Suddenly a fairy appeared and handed the youth a silver pipe chanter. When the boy played upon it, music more beautiful than ever before heard floated through the glen. It is hardly necessary to point out that the boy won the contest without difficulty.

Thus, it is the instrument itself that possesses the magical property; and this idea, of course, is reminiscent of the magical swords and ships of medieval legend, which of themselves possessed miraculous powers. Similar ideas about music are prevalent in Morocco: a person there who wishes to learn to play a musical instrument goes to the tomb of a certain saint, leaves an offering, and invokes the aid of the holy man’s spirit. The following day he awakes with an ability to play a musical instrument. Here again, this ability is specifically connected to magic.

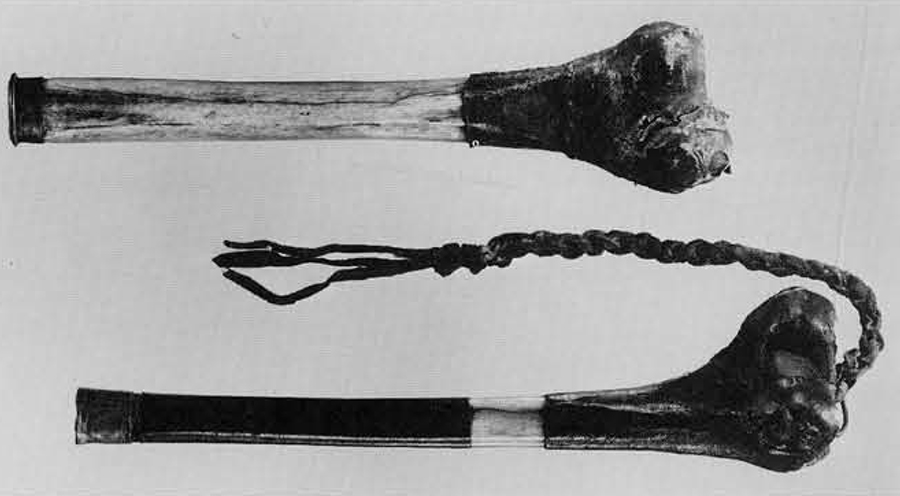

We very often find a specific legendary or physical connection between the human body and a musical instrument. This anthropomorphism is evident on such European instruments as the viola d’amore, which is generally surmounted with a carved human head. It is quite obvious in Sweden, where the player of the keyed fiddle known as nyckelharpa “regarded his instrument as a living thing and gave it a woman’s name. Its eyes were the sound holes and the instrument had to be hung with these the right way up. … Instruction by a water spirit who charmed souls with his playing is a persistent feature and the powers of darkness in the form of black hounds or the like are also said to have helped players become skillful musicians.” Far to the east of Sweden, the Mongols make the bridge of their fiddle khil-khuur from the lower jawbone of a human being. In Tibet, the ritual trumpet made from a human thigh-bone —often the player’s father’s—plays an important part in religious ceremony.

One of the most striking references to this anthropomorphic view of musical instruments is found, of all places, amongst the Arabs, who are forbidden by the Islamic religion from overt anthropomorphism. This tale was first written down in the ninth century by Ibn Salama; it might be summarized as follows:

The first man to make and play the Arab lute, al-ud (from which Europe gets both the name, lute, and the instrument itself) was Lamk (the Biblical Lamech). Though he had long been married, and though he had fifty wives and two hundred concubines, he had no sons, but at last, when he was an old man, a son was born to him, and he rejoiced. But the son died at the age of five, and his father was so grieved that he took the body, hung it on a tree, and said that he would never lose sight of his son’s body. But the body decayed until only the thigh, the leg, the foot, and the toes remained. So the father took a piece of wood, and following the shape of his son’s body, formed a neck to represent the leg, a peg-box the same size as the foot, and pegs like the toes; to this he added strings like his son’s sinews. Then he began to play on it; to weep, to lament, until he became blind.

There is no space here to probe into the meaning of the father’s act in hanging the body in a tree, though it seems clear that there may be an analogy to the Christian crucifixion and even to the agony of the Norse god Odin, whose suffering as he hung for nine nights on a wind-swept tree led to his learning the Nine Magic Songs. As with these acts, the body of the Arab boy hung in a tree became the subject of a kind of rebirth—in this case as a musical instrument. At the outset, we quoted a Scottish version of the Ballad of the “Twa Sisters.” The tale, in outline, tells us of two maidens who both love the same young man; he, however, prefers the younger. The older sister drowns the younger, whose body, when fished out of the sea, is made into a fiddle or a harp. In some versions, the story goes on to relate that when the newly-made instrument is played, it tells the sorry and grisly tale of the maiden’s death. Thus, though the girl is killed, her voice is heard again as an instrument.

Central to both the story of the lute and that of the “Twa Sisters” is the idea of a kind of symbolic resurrection in the form of a musical instrument which, however little it may look like its human model, is nevertheless founded upon it and sings with its voice. From this insight, it is but a step to a re-examination of the Orpheus legend, which has had a long and continuing influence far beyond the boundaries of its native Greece. As an example we might refer to another Scottish ballad, “The Twa Brothers,” where a bereaved maiden, weeping over the grave of her slain lover, is said to have put the small pipes to her mouth, And she harped both far and near, Till she harped the small birds off the briers, And her true love out of his grave.

In this, and all other versions of the Orpheus story, it is the power of song and instrumental performance that lifts the lover, however briefly, out of the realms of death. There are two closely related ideas here: in the first place, certain instruments are modelled after human beings and, thus in a way, are sounding statues. At the same time, the sound of an instrument can be sufficiently powerful to charm the dead out of their graves. Moreover, this principle operates in yet a third way. The flute, for example, is associated in most parts of the world with resurrection and the closely associated concept of fertility. The Babylonian god, Tammuz, was able to revive the dead when he played on his sacred flute; similar examples could be given from many cultures.

Freudians believe that it is the phallic shape of the flute that gives it its strong power, and this idea is supported by the fact that the flute is taboo to women in many societies (e.g., in parts of New Guinea). However, in the many societies where flutes are used in pairs, they are generally known as male and female; again, flutes are most frequently manufactured from cane or bamboo, and these materials, with their capacity for extremely rapid growth, have a fertility significance all their own. Thus, though the Freudian hypothesis may be true in certain places, there is no reason to assume that every society uses such symbolism.

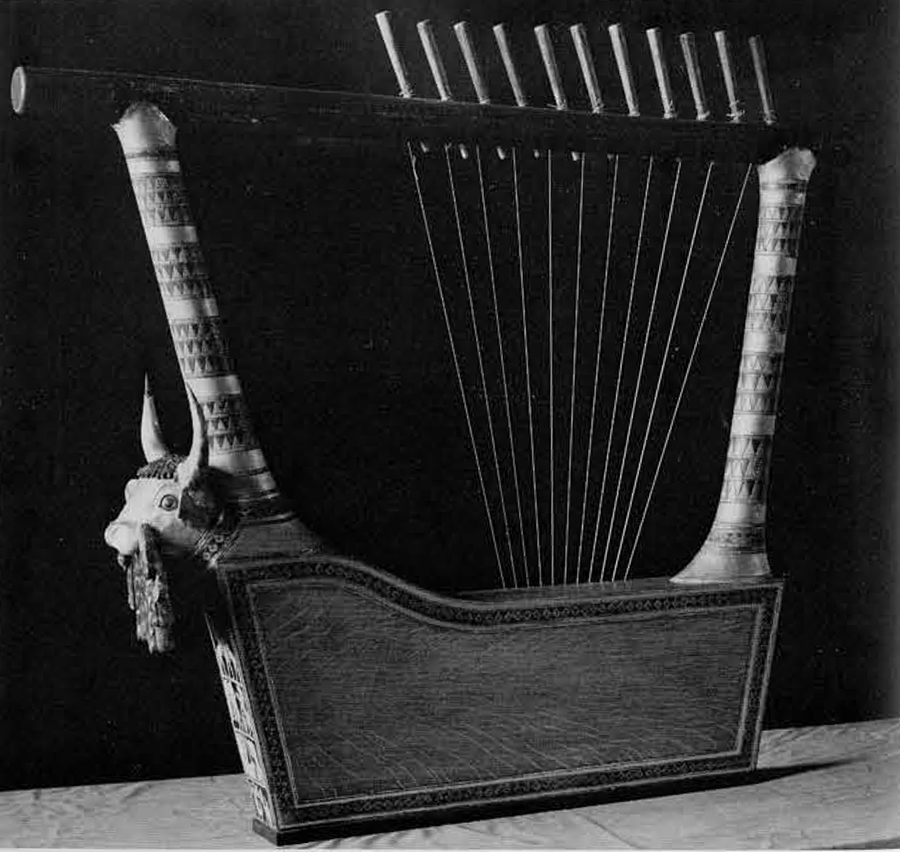

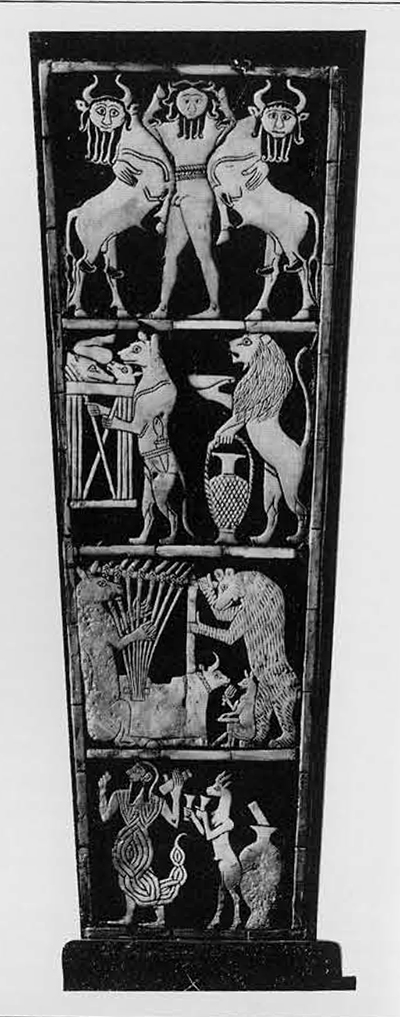

In many parts of the world, musical instruments are associated in shape or legend with powerful and significant animals, whose power is conserved in the instruments after the death of the animal itself. In Akkad, during the third millennium B.C., the head for the ritual kettledrum, known as lilissu, was made as follows:

A perfect black bull is selected and brought to the Temple; offerings are made, and the animal is singed; twelve images of the gods are placed near the beast; the body of the drum is set in place. Incantations are whispered to the animal through a reed; a hymn is chanted; the animal is slain. The skin is removed and treated, the twelve images are placed within the bowl; the skin is fastened to the drum. The bull, now personified in the drum, is taken finally into the presence of the gods of the temple.

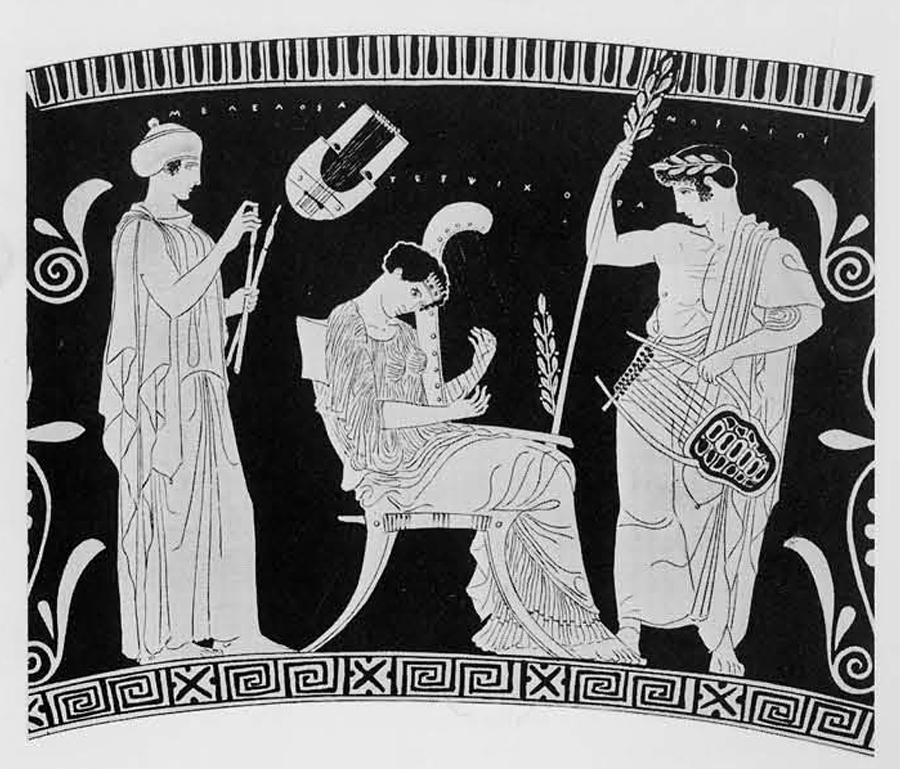

In this account it is quite clear that the essence and even the spirit of the slain bull would somehow survive in the material and sound of the drum. The bull, of course, had—and still has—a powerful significance in Western Asia and the Mediterranean; the term, “Bull-God,” is common in Mesopotamia; the sacred bull, Apis, was of great importance in dynastic Egypt; the Minotaur was a central figure in Cretan cult. Nowhere, however, was the bull more important than in Mesopotamia, and we might expect, therefore, to find considerable further evidence of this in the symbolism of musical instruments. And indeed, many lyres are surmounted with carved bulls’ heads, or in some cases the sound-chamber of the lyre is made in the form of a bull’s body. These bull-lyres were used both within and without the temples. Since the city-god of Ur was known as “Lord Wild Bull,” it is not inappropriate that a number of surviving instruments and representations of instruments should have been recovered there. Again, the connection between the lyre and the bull extends even to Greek myth—though in a less specific form. Myth reveals that Hermes, having stolen Apollo’s cattle, was deeply troubled, since he had been called into Zeus’ presence to explain his misdeed—though Hermes was at the time a new-born babe. On his way to the presence of this majestic god, he by accident kicked an empty tortoise shell, with the sinews still clinging to the inside. He picked it up in the realization that this new invention, presented to Zeus and Apollo, might well help atone for his transgression, And so it was: Hermes, having improved the instrument by the addition of seven oxhide strings, played it for Apollo, and then, seeing that the god was charmed by it, gave it to him. Tortoise-shell was in fact used by the ancient Greeks as the resonator of their lyres; and indeed, it is used today occasionally in those few places (mostly in East African cattle cultures] where the lyre is still played.

The theft of Zeus’ heifers was atoned for by the invention and gift of the lyre, itself certainly a cattle symbol. A lyre, seen from the front, with its two crosspieces resembling horns and its skin-covered oval resonating chamber (often with two holes resembling eyes], can be seen to resemble the bovine head—but perhaps this beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

In any case, the symbolic and magical associations of musical instruments extend far into the past and deep into the unconscious of their creators, players, and beholders.

In Europe, too, zoomorphic instruments are common; a clear example is the pastoral bagpipe, with its obvious symbolism of the herd of sheep or goats. Irish and Scottish harpers were of great and central importance to their culture; and to this day, the image of the Irish harp is stamped on the coinage of the country. The few surviving Celtic harps are normally elaborately carved; they in many cases exhibit the same tumultuous zoomorphism as do many other Celtic artifacts. One harp is surmounted with the figure of a woman, but the instrument is also provided with carved images of a number of animals issuing from the mouth of what appears to be a wolf. On another part of this harp is carved a pair of creatures with heads, wings, two legs, and long tails. The wolf, in Celtic tradition, seems to have had a special significance, and the gods of pre-Christian Ireland sometimes manifested themselves in this form. This exuberant piling of motifs on one another is entirely characteristic of the Celtic decorative arts.

In Celtic legend much is made of the role of bones washed up from the sea as the raw material from which musical instruments are made. We are told, in one tale, that Canola fled from her husband until she came finally to the seashore. There she heard the musical murmur of the wind as it played through the sinews clinging to the skeleton of a beached whale. Listening to this sound, she fell asleep, and when her husband came upon her and understood that the sound of this Aeolian music had calmed her, he made a framework of wood for the sinews. (In the Ireland of old, there were three categories of music, and one of these, suantrai, was music that caused the hearer to fall asleep.) In a Scottish version of the ballad, “Lady Isabel and the Elf-Knight,” the wicked knight performs similar magic:

He’s taen a harp into his hand,

He’s harped them all asleep,

Except it was the king’s daughter, Who one wink couldna get.

But what interests us mainly in the story of Canola is the use of the remains of a dead creature as the inspiration—and indeed the material—for the creation of a musical instrument.

A similar story is told in the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala. In this tale, the great hero of the cycle of stories, Wainamoienen, is sailing under a waterfall in a small boat when the vessel becomes stuck on the back of an enormous pike. Though others make the attempt, only Wainamoienen himself is able to slay the huge fish. After it is cooked and eaten, the hero, seeing the bones scattered, attempts to get the blacksmith, Ilmarinen, to make of them a musical instrument. But the smith refuses, and Wainamoienen himself takes on the task.

And he made a harp of pikebones, Fit to give unending pleasure,

Out of what did he construct it?

Chiefly from the great pike’s jawbones.

Whence obtained he pegs to suit it?

Of the teeth of pike he made them.

Out of what were harp strings fashioned?

From the hairs of Hiisi’s gelding.

No one, however, was able to draw music

from the instrument; so discordant was it,

that people listening to it gave it as their

opinion that it should be cast back into the

waters from whence it came. But the instrument itself answered:

No, I will not sink in water,

Nor will rest beneath the billows, But will play for a musician,

Play for him who toiled to make me.

So Wainamoienen himself begins to play on the instrument, which is known as the kantele, and all creatures—men, birds, wolves, bears, and even fish—assemble to hear the marvelous music played by this “joyous and primeval minstrel.” In another part of the Kalevala, the glorious instrument it lost at sea in a magically induced storm, but Wainamoienen, nothing daunted, eventually constructs another. At first, however, he wanders disconsolate through the countryside mourning the lost kantele; in a thick woods he listens to a birch tree lamenting its fate. It has been stripped by children and girdled by herdsmen, and it is on the verge of death. Wainamoienen, realizing that this tree can provide him with the material out of which to construct a new kantele, tells the tree that,

“New and charming joys await thee, Soon shalt thou with joy be weeping, Shortly shalt thou sing for pleasure.”

He then constructs the pegs from gold and silver that flow from the mouths of birds; he makes the strings from the hair of a maiden, and when the composite kantele, made from birch-wood, bird-song, and maiden-hair, was complete, Wainamoienen played the glorious instrument:

Sang the sapling green full loudly Loudly called the golden cuckoo, And rejoice the hair of maiden. The birch tree, of course, is a highly significant component of the folklore of northern Europe, and the body of the kantele is of course made of wood. But the significance of the story is greater than this alone. In the famous and deeply poetic passage from The Thousand and One Nights known as the “Song of the Lute,” the instrument, mourning its former verdancy, sings:

A tree while ere I was, the bulbul’s home, To whom for love I bowed my grass-green head;

They moaned on me, and I their moaning learnt,

And in that moan my secret all men read; The woodman felled me without offense, And slender lute of me (as view me)

made; But when the fingers smite my strings,

they tell How man despite my patience did me

dead.

The felled tree lives on as an instrument, and we begin to see deeper meaning behind the juxtaposition of the human body and the tree from which it was hung in the tale given by Ibn Salama.

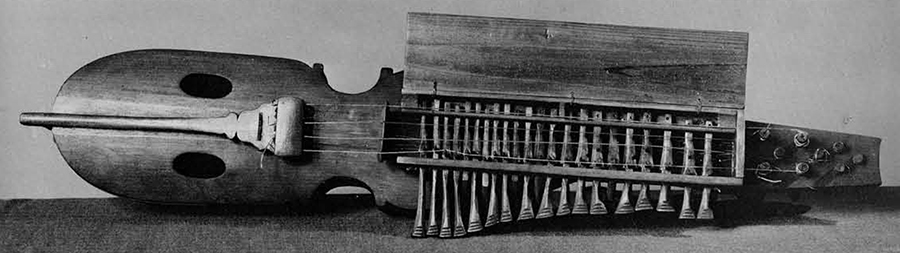

We have seen that Wainamoienen made the strings of his first kantele from horsehair, and of course this material is of fundamental importance to music, since it forms the bow-hair of nearly all fiddles—as well as the strings of a number of instruments. No creature in Eurasian belief is of greater or more fundamental importance than the horse, and thus we might expect that it would find its way into the lore of instruments as well as furnishing so prominent a constructional material. This indeed is so, and from Japan to Norway there is clear evidence that many stringed instruments have a symbolic relationship to the horse. Amongst the Mongols, the fiddle is provided with a carved horse’s head and, in this culture, which is so dependent on the horse as to have been dubbed a “horse culture” by anthropologists, this can hardly be simply an insignificant “decoration.” Indeed, a Mongol tale relates that the winged horse of the star-prince, exhausted and wounded, sank to the earth and died. The weeping prince caressed the body of his beloved steed, and while he did this, a miracle took place: the body of the horse was transformed into the first khil khuur (the Mongol horse-headed fiddle). The tuning pegs of the instrument are called chikhe (“ears”) and this seems to indicate in another way that the Mongols consider the instrument to be modelled after an animate creature.

Thus, it is interesting that in Japan the bridge of the shamisen is called by the word koma (“colt”), in China, the bridge of several stringed instruments are called ma (“horse”). The bridge of the North Indian bin is the kudirai—again, “horse.” Moving farther to the west, we find that the bridge of the Persian lute, tar, and the North African fiddle, rabab, are called by words that mean “donkey.” In many European languages, the same thing is true: the bridge of an instrument is frequently called by a name meaning “horse,” or “foal.” As far west as Norway, we find that the bridge of a Hardanger fiddle is called hest (“horse”). At the same time, this latter instrument is nearly always surmounted with a carving of a dragon— a symbol of deep and abiding significance in Norse mythology. (One thinks of the dragon, Fafnir, or of the dragonprowed ship built by King Harold Fairhair in 868.) The horse itself occupied an important position in the pre-Christian beliefs of the Norse: horse sacrifice was common, and, more significantly, horse fights were held in Norway in the spring to ensure good crops. The horse is connected, all across Eurasia, with fertility and fecundity. In view of all this, it can hardly be coincidence that the European violin itself has technical names for its parts that include, not only “belly,” “back,” “neck,” and so on, but more significantly, “saddle” and “tail-piece.” This bridge nomenclature would seem to be convincing evidence that the fiddle indeed did originate amongst the horse-cultures of Central Asia.

What does all this mean? Reviewing our evidence, we note that in case after case the instrument is connected with rebirth or fertility; with the symbols that are of deep and abiding significance to various cultures. In China, for example, the symbolic Phoenix bird—which is reborn from its ashes—is associated with a number of instruments: the bridge of the zither, ch’in, is a Phoenix forehead while the sides are Phoenix wings. Thus, all across Eurasia (and in the Americas and Africa as well, though we have not touched on these in this article) the meaning is the same—rebirth. If sometimes the symbolism is diffused, or if the same instrument has two apparently conflicting meanings, this only indicates the way in which for millennia musical instruments and their players have crossed and recrossed the continents, adapting and piling sometimes only dimly understood symbols on top of one another. At the same time, the passage of time itself has its effect on intermixing constantly shifting and blending symbols.

Animal symbolism is not especially appropriate to our age, for instance, and such once evocative terms as “iron horse” are almost entirely incomprehensible at present. Yet, what can be more symbolic of the industrial age than the symphony orchestra, with its uniformed functionaries, its managing director, its almost military precision? What, again, can be more redolent of the electronic age that follows than the rock and roll ensemble? Here every member of the group is linked by wires to the electronic heart of the ensemble; to complex electrical circuits—in fact, to more wires. If the modern electric guitar and drum set betray their ancient origins in their shapes, they equally betray, in their glittering plastic and electronic linkage, the new age growing, in an orderly—if not serene—way out of the old.

- Japanese moon guitar (left) European lyre guitar (right)

- West African anthropomorphic harp

- Greek fiddle, lyra

- Greek bagpipe, tsabouna, played by Mr. Tsamouris of Tarpon Springs, Florida

- Lyre from Uganda