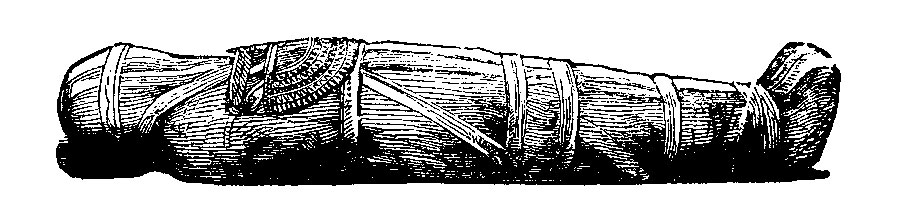

After 2,000 years of repose, 11 mummified human corpses and a few scrolls of papyrus entombed at Thebes became entangled in the interwoven threads of an Egyptian autocrat’s ambitions, the American public’s fascination with displays of the odd and exotic, and the formulation of the United States’ most prominent homegrown religion. Life after death has been far from dull for the only 2 surviving specimens of those 11 mummies, now lying undisturbed in the Penn Museum. The story of the remains that captured the attention of both early America’s most eminent physical anthropologist and the founder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints begins in the late 1810s, with the political machinations of the Egyptian viceroy, Muhammad Ali.

Ali, eager to modernize and militarize his country, ordered an exchange of Egyptian artifacts and mummies for European industrial machines and weaponry. He hired Antonio Lebolo, an Italian policeman and mercenary-archaeologist, to excavate scores of catacombs in the Valley of the Kings near Thebes. Through a series of excavations along the Nile conducted over almost five years, Lebolo and hundreds of Egyptian workers extracted 11 mummies and associated artifacts from a large Ptolemaic period (305–30 BCE) catacomb. Having collected thousands of antiquities for the viceroy’s exchanges across the Mediterranean, Lebolo was granted the Ptolemaic mummies as partial compensation for his service. Although he arranged for the transport of the mummies to Europe for consignment sale, Lebolo died prior to their arrival in 1830, leaving the exquisitely preserved corpses with his antiquities dealer.

From Egypt to the United States

Although no records detailing the transaction have survived, it is believed that Michael Chandler, an Irish-born entrepreneur living in Philadelphia, purchased the mummies directly from Lebolo’s dealer and had them shipped to New York in April 1833. Later, Chandler asserted that he had inherited the mummies from Lebolo, a claimed distant relation, but Lebolo’s will contains no mention of Chandler or the mummies.

Chandler, inspecting his purchase, unsealed the 11 mummies’ coffins to find fragile but intact rolls of papyrus interred with the bodies. Chandler immediately brought the mummies to Philadelphia and exhibited them for “a compensation” of 25 cents. The U.S. Gazette of Philadelphia reported in April of 1833 that “the largest collection of Egyptian Mummies ever exhibited in this city” was now on display in the Masonic Hall at 713–721 Chestnut Street. The announcement noted that the mummies were found “in the vicinity of Thebes, by the celebrated traveler Antonio Lebolo” and included “some writing on Papirus [sic] found with the mummies.” Although the famous Revolutionary-era American portraitist Charles Willson Peale opened one of the country’s first museums in Philadelphia in 1786—capturing attention with the display of a fossil Kentucky mastodon—public museums were still uncommon. Instead, early 19th-century Americans flocked to temporary displays such as Chandler’s, compelled by curiosity, and willing to pay a fee, to glimpse fabled Egyptian mummies. Mummies were a novelty for most Americans, as the first mummies had arrived in the United States, in Boston, only ten years earlier.

Morton Adds to His Collection

In an 1833 Philadelphia Daily Chronicle article, which reappeared verbatim in many other cities in which the mummies were exhibited, the pseudonymous writer “Pythagoras” urged readers to “spare 25 cents to see these fragments of mortality…The pouting lip, the bright and scornful eye, the panting bosom of the present beauty, will probably be more fleeting than the actual remains I now exhort my fellow citizens to contemplate.” Chandler further enticed potential customers with a “Certificate of the Learned” posted outside the exhibition, detailing the unsolicited endorsement of seven physicians “calling the attention of the public to an interesting collection, not sufficiently known in this city.” The May 21, 1833, minutes of the Academy of Natural Sciences report that Dr. Samuel George Morton, among the physicians who signed Chandler’s certificate, commented on “the remarkable development of the cranium in one [of the mummies].”

Following Dr. Morton’s exhortation, a Maryland newspaper noted that 9, not 11, mummies were on display in Philadelphia. This report coincides directly with Morton’s purchase of two of Chandler’s mummies: the founder of American physical anthropology, later renowned for his racist craniometric theories and his anatomical collection of human crania—the “American Golgotha”—listed his new acquisitions in his Catalogue of Skulls as numbers 48 and 60. The former was reported to be the “embalmed head of an Egyptian girl, eight years of age, from the Theban catacombs” and the latter as the “embalmed head of an Egyptian lady about 16 years of age brought from the catacombs of Al Gourna, near Thebes, by the late Antonio Lebolo, from whose heirs I purchased it, together with the entire body.” Only the mummies’ heads were retained by Morton after he dissected their bodies at the Academy on December 10 and 17, 1833.

Joseph Smith Purchases Mummies and Papyri

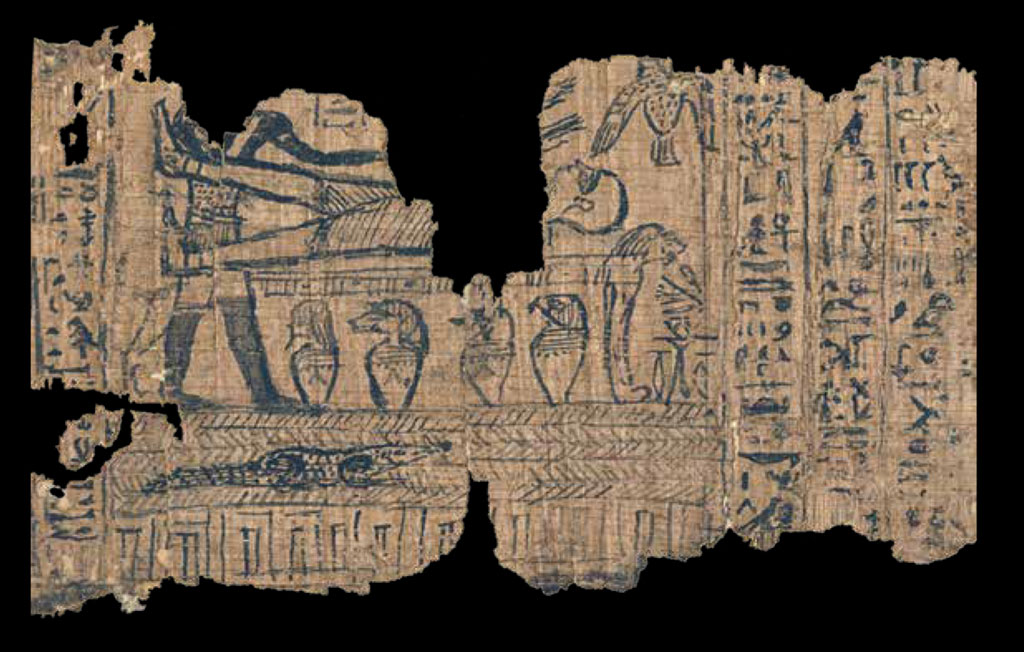

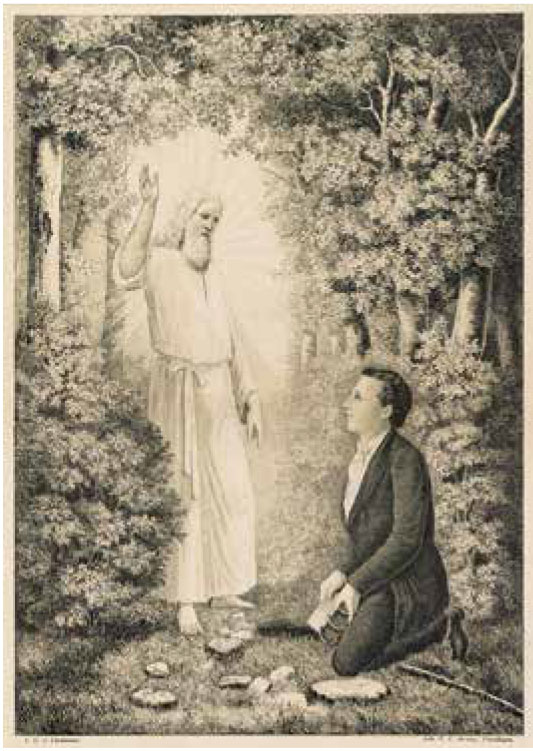

Taking the show on the road, Chandler traveled with the remainder of his mummies along the East Coast and into Appalachia, continuing to exhibit and sell the corpses until he had only four mummies and some articles of papyrus in his possession when arriving in the town of Kirtland, Ohio, on July 3, 1835. This hilly Northeast Ohio town served as the center of the Latter Day Saints (LDS) movement after the prophet Joseph Smith relocated from upstate New York in 1831. Chandler was drawn to the fledging religious community following Smith’s claims of having translated a holy book called the Book of Mormon, allegedly inscribed in an ancient Egyptian language on golden plates found buried in Palmyra, New York. Although Jean-Francois Champollion had deciphered hieroglyphics with the use of the Rosetta Stone in the early 1820s, this scholarship was unavailable to Smith and the American linguists that Chandler consulted concerning the meaning of the inscriptions on the papyrus. On July 6, Smith noted in his diary that the “Saints at Kirtland” purchased the mummies and papyrus for the hefty sum of $2,400, finishing off Chandler’s collection and providing Smith with raw material for another divinely inspired translation of mysterious texts. Chandler retired to more mundane pursuits and settled on a farm.

Over the course of 1835, Joseph Smith claimed to have translated the papyri, stating that they were an account of revelation from the biblical figure Abraham. His translation and facsimiles of the hieroglyphics were published as the Book of Abraham in the Pearl of Great Price, a canonical text in the LDS Church. The four mummies and papyri were kept by Joseph Smith until his death at the hands of a mob in 1844. The collection passed to Smith’s mother and was purchased by Abel Combs in 1856, who retained two of the mummies and some of the papyrus fragments. He sold the other two mummies to the Woods Museum in Chicago, destroyed by fire in 1871. The whereabouts of Comb’s two mummies are unknown, although his papyrus fragments were passed on through his family and sold to the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMA) in 1947. In 1966, a historian researching in the MMA archives recognized the fragments from Smith’s facsimile in the Book of Abraham. An anonymous donation allowed for their acquisition by the LDS Church Archives in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Smith’s translation of the papyri was canonized by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints in 1880. Egyptologists, now able to translate the hieroglyphics, have investigated the surviving papyri fragments and Smith’s facsimiles. All remark that they bear no resemblance to Smith’s translated Book of Abraham, but are common Egyptian funerary texts. Mormon apologists and their critics continue to debate the text, which contains some of the most idiosyncratic doctrines of the LDS church, such as the name of the star, Kolob, which is closest to the throne of God, and the existence of other deities and inhabited worlds. Despite controversy, the text derived from Lebolo’s papyri remains a part of official LDS canon.

Since Chandler did not document the sale of the mummies during his travels and since the location of Comb’s mummies is uncertain, the only known remaining mummies from Lebolo’s collection are those purchased by Samuel Morton in Philadelphia. In the 1960s, the Penn Museum acquired the mummified heads in Morton’s collection of human crania from the Academy of Natural Sciences. In 1979, Mormon scholar H. Dohl Peterson at Brigham Young University (BYU) arranged a four-year loan of mummy 60, resulting in an exhibition at BYU that closed 150 years after the mummies’ arrival in the United States. Today, the Penn Museum’s Physical Anthropology Section provides a secure afterlife for these seasoned travelers, the last known bodily remains of the only cohort of mummified bodies to inspire a major religious text in American history.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Dr. Janet Monge and Dr. Alan Mann for their invaluable advice on this manuscript, and the staff at the American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, for their kind assistance.

Paul Mitchell is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania.

For Further Reading

Gee, J. Guide to the Joseph Smith Papyri. Provo: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2000.

McDonald, M.E. “Rerolling the Joseph Smith Papyri.” The Society for Early Historic Archaeology 146.0 (1981): 1-5.

Morton, S.J. Catalogue of Skulls of Man and the Inferior Animals. Philadelphia: Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 1849.

Peterson, H.D. The Book of Abraham: Mummies, Manuscripts, and Mormonism. Springville, Utah: Cedar Fort, 2008.

Rhodes, M. The Hor Book of Breathings: A Translation and Commentary. Provo: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2002.

Smith, J. History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City: Deseret, 1973.