For the past year one of the projects of the University Museum has been the renovation and remodeling of the South Pacific and African storerooms. with more efficient storage units, better lighting, and the installation of air filters which will prevent the accumulation of dust, it has been possible to give the collections, which are some of the best in the United States, the care they deserve, and at the same time, to provide pleasant work areas in the storerooms for the use of visiting scholars as well as the museum staff and students.

Image Number: 250

To facilitate the use and study of the objects, the collections are separated into geographic and/or cultural groups. In the Pacific storerooms all the pieces from a particular island or group of islands are stored together, except where size or material makes special arrangements necessary. It was while separating them and checking their identification against the catalog cards that I became interested in how some of the Pacific islands got– and kept– their names. This is of some significance in working with the collections.

Islands and island groups have shown a disarming tendency to change their names from time to time in the past, and this process is by no means over. It seems that every time an island group has its allegiance to a world power changed, the new possessor is liable at worst to bestow a whole set of new names on the individual islands and geographic features, or, at best, only to change the spelling of the previous names. Thus, when Germany acquired in 1884 what is sometimes called North-east New Guinea or German New Guinea they named it “Kaiser Wilhelm’s Land”; it remained a German colony until World War I; in 1920 the area was awarded to Australia by the League of Nations and called the Mandated Territory of New Guinea. After World War II it became the Territory of New Guinea, under a trusteeship to Australia from the United Nations, until 1949 when it was amalgamated officially with the Territory of Papua (that is, with the southeastern portion of New Guinea, formerly called British New Guinea) and both parts are now known as the Territory of Papua and New Guinea. For several reasons, this is a rather simple example: the name New Guinea was preserved in most of the titles; New Guinea is a rather large chunk of land and consequently not easy to lose; it was of some importance economically and therefore received considerable attention from the outside world; and the name-shifting occurred in the days of good facilities for widespread communication.

However, if one can’t lose this large portion of New Guinea, one can get rather confused over New Guinea’s largest river, the Sepik. Many different tribes live along this meandering, 700-mile long river, and some of them produce quite distinctive and pleasing carvings. In the Museum’s collection of these carvings, some are reported as coming from the Kaiserin Augusta River which they did at the time they were collected, for this is what the Germans call Sepik (or Sepic, as it is sometimes spelled).

For many of the smaller Pacific islands, the reasons and history of their name-changing are not quite so easy to trace. Very often, in the early days of European exploration of the Pacific, islands were “discovered” several times and each discoverer gave the island a new name. Even if Captain A knew of Captain B’s discovery he wasn’t always sure it was the same island since accurate positions were hard to fix in those days. He had two choices: he could assume the island had been discovered by B and could call it by the same name, but if it wasn’t the same, and if A’s position was not the same as B’s, which was quite likely, then the same name had been recorded for two different islands in two different positions; or he could assume that he had discovered a new island and give it a new name, and if it happened to be the same island, it then had been reported, probably in two different positions, with two different names. To illustrate how this process of confusion works, let’s follow several early European navigators through the Marquesas Islands.

Museum Object Number: 55-33-1

Image Number: 61947

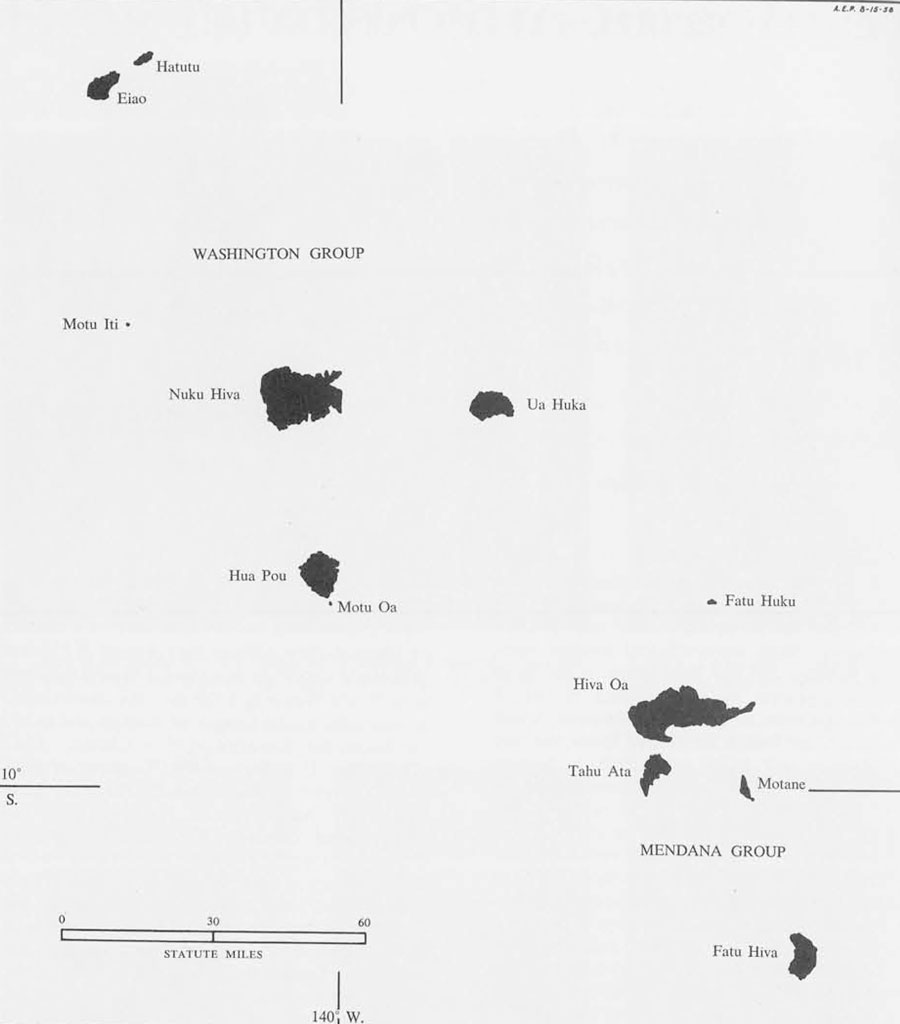

The Marquesas are a group in eastern French Oceania more than 700 miles northeast of Tahiti, lying between 7 TK 50′ and 10 TK 33′ South latitude and between 138 TK 26″ and 140 TK 44′ West longitude. They consist of ten fairly high islands and several small islets and isolated rocks. The high islands today are usually known by their native names* and are, from north to south: Hatutu, Eiao, Nuku Hiva, Ua Huka, Hua Pou, Fatu Huku, Hiva Oa, Tahu Ata, Motane, and Fatu Hiva.

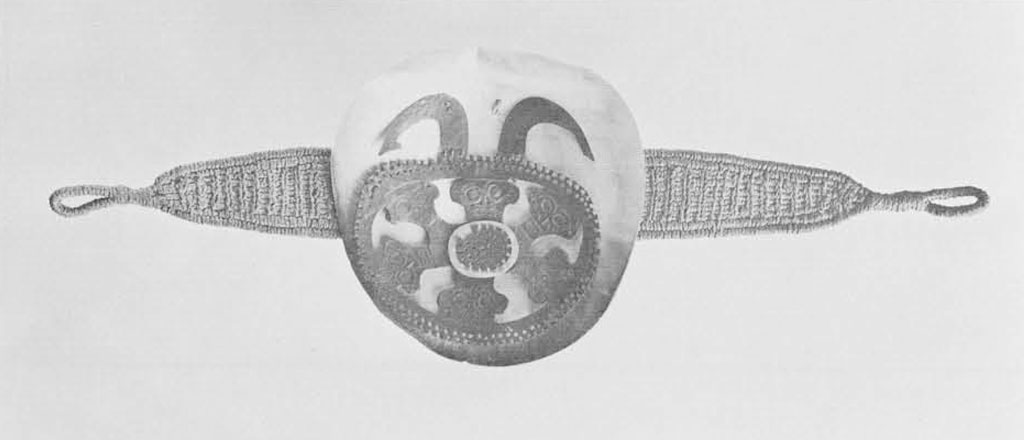

On modern maps the double names are sometimes joined together in a single word, as in Tahuata and Nukuhiva; on French charts the names are usually spelled with an o proceeding every u, as in Ouahouka. This latter island, Ua Huka, is also sometimes listed by another native name– Huahuna. The Marquesans are Polynesians who were quite skilled carvers of stone, wood, bone, and ivory. The beauty of their islands — and of themselves– was made famous in the Western World by such writers as Robert Louis Stevenson and Herman Melville, and by the French painter Paul Gauguin who lived, died, and is buried on the island of Hiva Oa.

The Marquesas Islands have the distinction of being the first Polynesian islands of any significance to be discovered. On his second voyage in the Pacific the Spanish navigator Alvaro Mendana de Neyra, sailing from the port of Callao with four ships, discovered, on July 21, 1595, the southernmost island, Fatu Hiva, and named it “Santa Magdalena.” He went on to discover three more of the southern islands, naming them “Santa Christina” (Tahu Ata), “La Dominica” (Hiva Oa), and “San Pedro” (Motane). To the group he gave the name of “Las Islas de Marquesas de Mendoza” in tribute to Don Garcia Hurtado de Mendoza, Marques de Canete, Viceroy of Peru at that time and patron of the voyage. One source claims that the group was named for the Viceroy’s wofe, which might be more correct grammatically. These islands, together with Fatu Huku, are now referred to collectively as the Mendana or Southeast Group, while part of Mendana’s title– Marquesas– is applied to the whole group.

It is interesting to note that Mendana got European-Marquesan relation off to what history has proved to be a typical start by massacring around two hundred natives on Fatu Hiva. Fate may have extracted some justice for this cruelty, however, for Mendana sailed on across the Pacific in the same latitude and thus managed to miss discovering the other important groups in Polynesia. (This was the second time he had done this: on his first voyage, in 1567, he accomplished the remarkable feat of sailing across the south Pacific without discovering a single island in Polynesia proper!) Anyway, Mendana did reach the island of Santa Cruz, or Ndeni in the Santa Cruz group, where he attempted to establish a colony. The attempt failed after Mendana and forty-seven of his men died (probably from malaria); the survivors were under the nominal command of Mendana’s widow, but his pilot, Pedro Fernandez de Quiros, took charge and managed to get them to Manila. There the widow married the Governor of the Philippines, ten more men died, and four others entered monastic orders perhaps to ensure, as Peter Buck in Explorers of the Pacific put it, “a future less troubled than their past.”

Quiros himself escaped both death and religion, guided the remnants of Mendana’s expedition back to Acapulco in 1596, and lived to sail Pacific waters again in 1605 with his own expedition, and discovered several important islands in the New Hebrides group. (Just to continue the story, the commander of Quiros’ second ship was Luis Vaez de Torres who, after getting separated from Quiros when they left the New Hebrides, went on to discover the strait between Australia and New Guinea which now bears his name.)

Image Number: 62795

However, to return to the Marquesas Islands: Mendana may have left bad memories behind him but time had an opportunity to ameliorate them, for it was almost two hundred years before another explorer found the group. This explorer was the most famous of all Pacific navigators, Captain James Cook. On his second voyage Cook, attempting to locate Mendana’s discoveries, found first the only island in the Southeastern Group which Mendana had missed– the small island of Fatu Huku which Cook named Hood’s Island after the midshipman who first sighted it. This was in April, 1774, and after locating all of Mendana’s islands except Fatu Hiva, and obtaining refreshments, Cook sailed on to Tahiti.

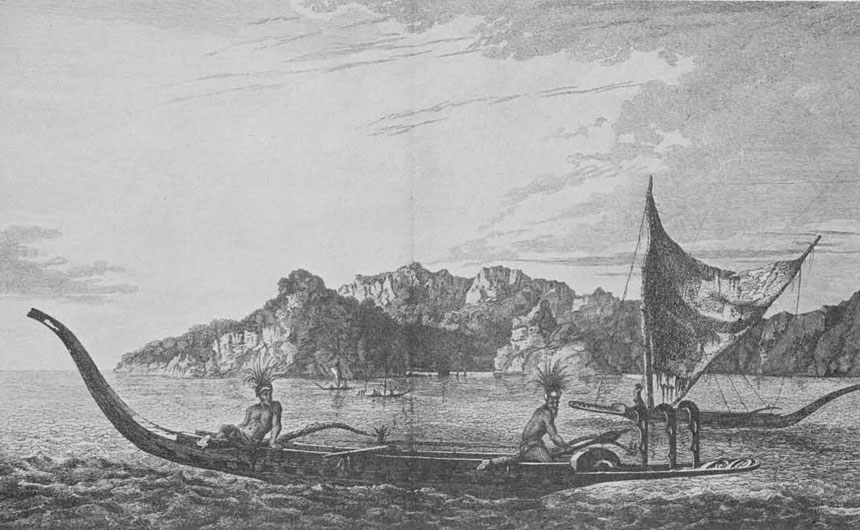

The next navigator to happen on the Marquesas was Joseph Ingraham, master of the brig Hope. The Hope was Boston-owned and had sailed from that port on September 17, 1790, on a trip around the world via Cape Horn, the northwest coast of North America, China, and eventually home around the Cape of Good Hope. In April, 1791, Ingraham sighted the Mendana group. Five days later, on April 19th, he sailed north-northwest from “La Dominica” (Hiva Oa) and the same day sighted two new islands: Ua Huku and Hua Pou. Ingraham must have been a patriotic man for he named Ua Huku “Washington” after the President of the United States and bestowed Vice-president Adams’ name on Hua Pou– the Lincoln was for General Benjamin Lincoln, not Abraham).

When he couldn’t find a favorable place to land, Ingraham assembled his crew and proclaimed United States possession of the newly discovered islands. On April 20th they found Motu Iti (literally, a “little island”) and named it “Franklin” in honor of Benjamin Franklin. Still sailing north and west they next encountered Hatiti which was awarded the name “Hancock” after the Governor of Massachusetts, and then Eiao which was named for General Henry Knox. Today this North-west group is referred to as the Washington group.

Museum Object Number: P3282

Image Number: 21252

Between Mendana, Cook, and Ingraham, all of the large islands and some of the small ones in the Marquesas had been discovered by 1791. The Mendana group had been well verified and were known to mariners under Mendana’s names. However, news of Ingraham’s discoveries didn’t reach other navigators for awhile so these islands were “discovered” several times over in the next two years.

Close after Ingraham– only two months later– came the Frenchman, Captain Etienne Marchand. Marchand had heard of the rich fur trade on the northwest coast of America and persuaded some Marseilles merchants to fit a ship for him. Sailing northwest from the Mendana group he, too, saw Ua Pou– and named it for himself. The small island off Ua Pou– Mota Oa, which Ingraham had called Lincoln– was named “Ile Plate.” When Marchand saw Nuku Hiva he named it “Ile Baux,” after the owners of his ship. Motu Iti (Ingraham’s “Franklin”) was found to be two small islands close together so Marchand dubbed them “Les Deux Freres.” Sailing on, he encountered Eiao and Hatutu which he named “Masse” and “Chanal”, respectively, after his two captains. One can see that Marchand’s system of naming was much more personal than the patriotic Ingraham’s. Because Ingraham’s journal was never published (it is reported to be in the possession of the Literary and Historical Society of New England), for a long time Marchand’s claim of original discovery of the northwestern islands was not questioned.

Museum Object Numbers: 18541A / 18541B

Image Number: 56183

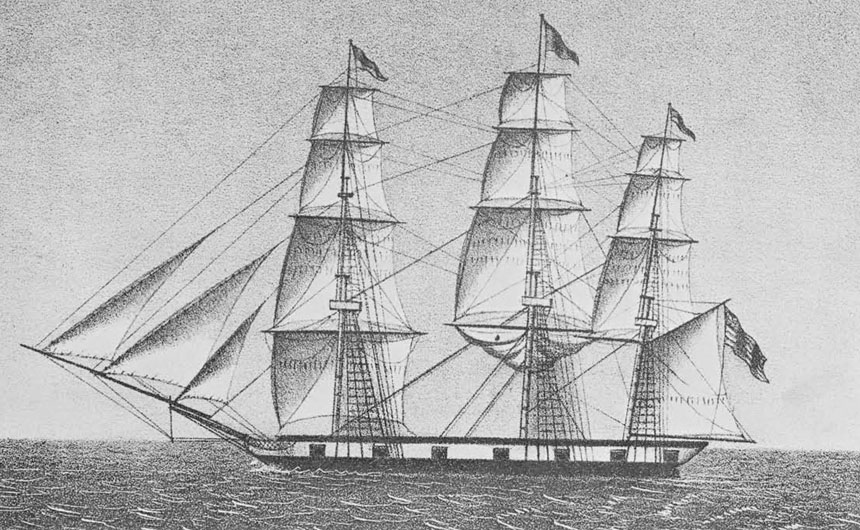

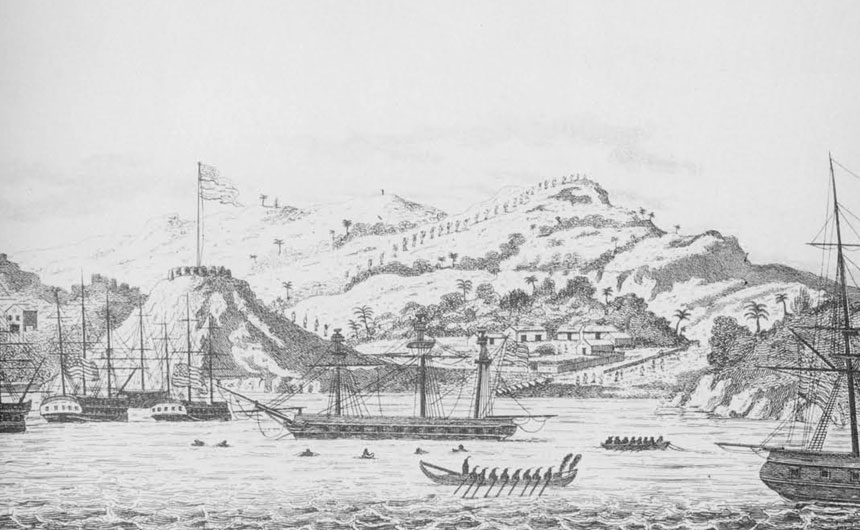

Less than a year after Marchand had been in these waters, England was again represented in Marquesan discovery in the person of Lieutenant Richard Hergest in the Daedalus. Like the Spaniard Mendana, the English Cook, and the American Ingraham, Hergest’s voyage was primarily in South Pacific affairs but rather in North American, for his was the store ship on Captain George Vancouver’s expedition to survey the northwest American coast. Vancouver’s Discovery, and his second ship, the Chatham, commanded by Lieutenant W. R. Broughton, sailed before the Daedalus and went via the Cape of Good Hope, New Holland (Australia), and New Zealand.

The Daedalus had sailed around Cape Horn and, according to schedule, rendezvoused with the other two at Monterey. When Vancouver met the Daedalus there he found it under the command of the Master, and learned that Hergest, his astronomer, and a sailor had been killed on Oahu in the Hawaiian Islands. From Hergest’s papers Vancouver learned that on March 30, 1792, he had sighted three islands: Ua Hoku, which he named “Rious,” Hua Pou, which he named “Sir Henry Martin’s Island.” Later he named the rocky islets of Motu Iti “Hergests Rocks,” after himself, and the two islands of Eiao and Hatutu he called “Roberts Islands.” Vancouver, like Hergest, knew nothing of Ingraham’s and Marchand’s visits the previous year, and supposed the islands to be new discoveries; he named the whole group “Hergests Islands.”

Museum Object Number: 18016A

Image Number: 73

The next voyage was of a commercial nature, and like his recent predecessors, Josiah Roberts in the Jefferson from Boston, did not know of the previous discoveries. Roberts was heading for the northwest coast, too, and he carried in his ship the materials to build a schooner in the Marquesas. He arrived at Tahu Ata (Mendana’s “Santa Christina”) in November, 1792, and stayed more than three months in Resolution Bay while building his schooner. Roberts became well acquainted with the natives and from them learned of the existence of the islands to the northwest. When his new ship was ready, Roberts sailed for Hua Pou which he named “Jefferson” after his own ship, and the small island off Hua Pou (Motu Oa) he named “Resolution” after his new schooner which had been given the name of the bay in which it had been built (and the bay had been named for Cook’s ship, the Resolution). Nuku Hiva he labeled “Adams” (remember that Ingraham had given this name to Hua Pou); Ua Huka was designates “Massachusetts” while Motu Iti was named “Blake Island.” While sailing among these islands Roberts had a native of Nuku Hiva with him, and this old man gave Roberts the native names of the islands for the first time.

This man was left on Nuku Hiva, and Roberts sailed on north and found Eiao and Hatutu on March 3, 1793, and called them “Freeman” (one source says “Freemantle”) and “Langdon”, respectively. To the whole group of northwestern islands, Roberts gave the term Washington Islands.

The next voyage was also an American one: that of Captain Edmund Fanning in the Betsey, owned by Mr. Elias Nexsen of New York, and sailing from Stonington, Connecticut. Fanning was after fur seals, which he found in abundance at Masafuero Island (in the Juan Fernandez Islands). After loading his ship he sailed for the Marquesas for refreshments. At Tahu Ata he found the missionary William Crook who had been left there the year before (1797) by the missionary ship Duff. Crook had found the Marquesans rather unfriendly and beseeched Fanning to take him off the island.

Image Number: 62796

He told Fanning of the four large islands to the north which had been named Washington Islands (by Roberts). Fanning sailed to this group in the hopes of getting more fresh food. He succeeded at Nuku Hiva with Crook’s help; apparently the latter thought these natives more hospitable since he left the Betsey and remained there. Fanning sailed on north and, after he had found the four islands by Crook, and then found two more, he thought they were new discoveries and christened Eiao “New York” and Hatutu “Nexsen” after the owner of his ship.

(Fanning continued sailing north and west and truly discovered two small, uninhabited, isolated islands: Fanning, which he named for himself, and Washington, named for the president of the United States. He also sighted, but did not name, Palmyra Island, which was named in 1802 by Captain Sawle after his ship. Fanning went on across the Pacific, unloaded his fur seal cargo at Macao and acquired one of tea, silk, nakeen, and chinaware which he took back to New York via the Cape of Good Hope. He reached New York on April 26, 1799, and he reported in his account of the voyage that his round the world expedition had a profit of $52,300.)

The last mariner to be involved in this confusion of naming the Marquesas Islands was Captain David Porter, and his story is a rather interesting one too. During the War of 1812 Porter had command of the frigate Essex and his mission was to harass British shipping. After considerable success in the Atlantic he rounded Cape Horn– without orders– continued his harassing and finally made for the Marquesas for fresh supplies with a flotilla of captured ships in tow. Porter must have been flushed with his successes and carried away by the spirit of war. He landed at Nuku Hiva, camped ashore and made friends with the natives. He assisted them in their own little war campaigns with each other, and when native affairs became rather messy he decided to take possession of the island. This he did on November 19, 1813 in a formal declaration, which was published by his biographer, Archibald Douglas Turnbull, in Commodore David Porter 1780-1843. The declaration comences and reads in part:

Image Number: 62797

“It is hereby made known to the world that I David Porter a captain in the navy of the United States of America and now in command of the United States frigate the Essex, have on the part of the said United States taken possession of the island called by natives Nookaheebah, generally known by the name of Sir Henry Martin’s Island, but now called Madison’s Island [for President Madison]. That by the request and assistance of the friendly tribes residing on the mountains, whom we have conquered and rendered tributary to our flag, I have caused the village of Madison to be built consisting of six convenient houses, a rope walk, bakery and other appurtenances, and for the protection of the same, as well as for that of the friendly natives, I have constructed a fort calculated for mounting sixteen guns whereon I have mounted four, and called the same Fort Madison…

…and that the act of taking possession was announced by a salute of seventeen guns from the artillery of Fort Madison, and returned by the shipping in the harbor, which is hereafter to be called Massachusetts Bay. And that our claim to this island may not be hereafter disputed, I have buried in a bottle at the foot of the flagstaff in Fort Madison, a copy of this instrument together with several pieces of money, the coin of the United States.”

The bottle was dug up a year later. Many of the natives gave allegiance to the United States, the island was subdued, and Porter sailed away in search of more glory, leaving three of his prizes and some prisoners in charge of a few of his men. An English resident of the island, who had assisted Porter as an interpreter, didn’t like the new turn of affairs, led the natives in a revolt, and murdered some of the remaining Americans. A few of them escaped and sailed to Hawaii. There, by a twist of irony, they were captured by the same British frigate that a few weeks earlier had caught up with the dashing Porter and helped capture him in the Essex. Even if Porter’s career was sometimes a bit too flamboyant for his superiors’ liking, he served his country well in more ways than one, for in his household were two future admirals of the U.S. Navy, his own son, David Dixon Porter, and an adopted son, David Farragut.

Image Number: 62761

The United States never ratified Porter’s annexation, and the only people who contested France’s annexation of the whole group thirty years later were the natives who resisted so fiercely on the island of Hiva Oa that it acquired the nickname of Bloody Hiva Oa.

So ends the rather complicated story of the early history and naming of the Marquesas Islands. Who bestowed a few other names, like the title “Isle of Barking Dogs” on Motane, or “Gunner’s Quoin” on Motu Oa is not known, and we have not considered the alternate native names, nor alternate spellings. In the following summary of this variety of names, the current names are given first.

North-west or Washington Group: Isles de Revolution, Hergests Islands: Hutu: Fatuuhu, Fetouhouhou, Hancock, Chanal, Langdon, Nexsen.

Eiao: Hiau, Knox, Freeman or Freemantle, Roberts, New York, Masse.

Motu Iti: Motuiti, Franklin, Les Deux Freres or Two Brothers, Hergest Rocks, Blake.