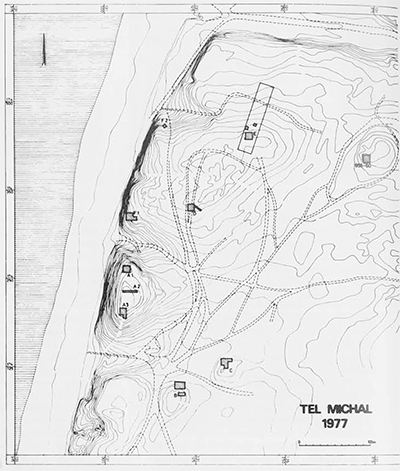

Tel Michal (Makmish) is situated on a kurkar (sandstone) ridge covered with sand dunes in the southern environs of the modern city of Herzliya at a distance of 6.5 km. north of the Yarkon estuary and 4 km. south of ancient Arsuf-Apollonia. It is an extraordinary site, with archaeological remains dispersed over five hills: a high tel overlooking the Mediterranean, a slightly lower hill lying north of this tel, and three low-lying hillocks towards the east.

This is the site selected for excavation in the summer of 1977 as the first phase of a regional project aiming at the exploration of the southern Sharon and northern Philistine coast. The project is a joint endeavor, initiated by the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University, in which several overseas institutions are participating, including Brigham Young University of Utah, the University of Minnesota, the University of Pennsylvania and Macquarie University of Australia. Directed by Prof. James D. Muhly of the University of Pennsylvania, the project is focused on studying the history of the western Yarkon basin in an attempt to reach a complete settlement picture of this region, the eastern part of which is being explored by the Aphek-Antipatris expedition. Prof. George Rapp of the University of Minnesota and Nathan Bakler of the Geological Institute of Israel are conducting a geological survey of the kurkar ridges of the Central Sharon, while Dr. Ram Gophna of Tel Aviv University and Dr. Bruce Warren of Brigham Young University are carrying out an archaeological survey of the Sharon plains from the Yarkon River in the south to the Poleg River in the north. Prof. Aharon Horovitz of Tel Aviv University is attempting to trace the possible existence of a boat jetty whose remains may lie under the sea at the foot of Tel Michal.

Site Description and History of Exploration

The high tel, rising to an overall height of 30 meters above sea level, is elliptical in shape, measuring about 85 meters from north to south and 50 meters from east to west. It is cut off from the rest of the kurkar range at its north and south by two deep ravines running into the sea. Its eastern slope is covered by thick deposits of wind-borne sand, but the harsh southwestern winds have completely denuded the southern slopes, not only of the accumulated sand but of any traces of occupation later than the Hellenistic period. The western side of the tel is a veritable cliff jutting abruptly from the narrow beach below; open to the winter storms coming from the west, it is also badly eroded. The damage being wrought by these erosional forces—not to mention the depredations of modern antiquities robbers—was one of the factors determining our choice of this site for an urgent salvage operation.

Beyond the northern ravine, the “lower city” is located on a rectangular-shaped hill, measuring approximately 250 meters from north to south and 175 meters from east to west, and about five meters lower than the high tel.

The three low mounds at the east were apparently independent architectural units, since they are separated from the high tel and the “lower city” by sand dunes in which no archaeological remains could be traced. The largest one, approximately 2500 square meters in size, is about 400 meters northeast of the high tel. It was partially excavated by a previous expedition directed by Prof. Nachman Avigad. The findings were of a ritualistic character, represented in strati-graphic sequence by an open courtyard (a High Place ?) dating to the 10th century B.C.; a Phoenician temple yielding quantities of stone and pottery figurines and miniature incense altars of the 5th century B.C., and a small altar standing inside a temple court dated by Ptolemaic coins to the 3rd century B.C.

The second mound (Area B), about 150 meters southeast of the high tel, rises only five meters above its immediate surroundings the third mound (Area C), of similar height, is about 80 meters east of the former.

The site was first discovered in 1922 by J. Ory, archaeologist of the British Mandatory Government, who located its principal components but was under the impression that they made up a contiguous settlement of some 800 x 500 square meters; he also thought that its existence was limited to the Persian and Hellenistic periods, whereas subsequent surveys have established that the site was occupied also in the Middle Bronze, Late Bronze and Iron Ages, although not without some intervals of desertion. Noting that the area surrounding the tel appears on the maps of the Survey of Western Palestine as “Dharat Makmish,” Ory explained the origin of the name as follows: “Makmish is obviously derived from Mekal. The name Makmish was derived from Maklish by the usual interchange of the succeeding letters L and M of the Arabic alphabet in the local vernacular, and in its turn, Maklish was derived from Amyklaios, the Apollo-Amyklaios of the Greek inscriptions from Cyprus.” On the basis of this interpretation, the Israel governmental names committee decided in 1959 on the name Tel Mikhal, and so it appears on the maps of today, although there are no data as yet to establish the ancient name of the site. However, we follow the Biblical spelling of the personal name of Michal, daughter of King Saul.

The Excavations

The first season of excavation was carried out for four weeks in the month of July 1977; its goals were to determine the limits of the site, to check the stratigraphic sequence in the upper tel and the mounds, to search for a “lower city” on the northern hill and to locate the industrial districts and burial grounds of the settlement. Eight areas were opened up: three on the upper tel and five in the surrounding areas. Because of the great distances between these areas and the lack of any architectural connection, no attempt was made to correlate the strata by means of a comprehensive numbering system.

The upper tel: Three areas were opened, designated as Al, A2 and A3 from north to south. At the northern end of the tel, the area (A1) was covered by sand dunes more than two meters deep at some points, which had to be removed before digging could commence. First the northeastern corner of a large Hellenistic building, exhibiting two architectural phases, was uncovered, but since its western half was badly eroded and the rest of its remains disturbed by antiquities robbers, it was difficult to determine its floor plan; it was mainly the eastern stone foundation wall, about 70 cm. wide, that was preserved. Two Seleucid coins of Antiochus II and Demetrius II date these Hellenistic levels to the mid-3rd to mid-1st centuries B.C. Underneath these remains parts of flooring from the Persian period were found. There was also a brick wall 1.40 meters thick, such thickness indicating that it belonged to a public building.

The area at the center of the upper tel (A2), also covered by sand dunes, was opened in order to study the stratigraphy of the later stages of the settlement, which are missing elsewhere at the site. In the upper building level a 1.10-meter wall was uncovered, which ends in a square buttress, unfortunately ransacked in antiquity, leaving only its foundation. From the white lime floor extending onto this buttress, sherds of Khirbet Mafjer (Early Arabic) type were collected; fragments of plaster with relief decoration, found in the robbers’ trench, probably decorated the upper parts of this wall. Under the buttress and wall was discovered another wall, similarly oriented, with a plastered entrance 1.10 m. wide, and three parallel walls perpendicular to it, but no corresponding floors were found. However, in the adjacent filling, the latest pottery found dated to the Roman period; this dating is confirmed by a coin found in the robbers’ trench belonging to the Julio-Claudian dynasty and minted in Antioch. This Roman building seems to stretch at least 19 meters from east to west; it was most likely a fort built at the top of the tel to guard both the land and the sea approaches.

Underneath the Roman remains, two walls were uncovered at the eastern edge of the area, and part of a floor at the western edge. Here a small treasure of seven coins was discovered: five Macedonian coins struck by Cassander, one of Alexander the Great and one Ptolemaic coin. Together with the ceramic material, these coins give a date at the end of the 4th to the beginning of the 3rd centuries B.C. for this Hellenistic level. Sherds of the Persian period and even some of Iron Age II were found in this area, but our excavations have not yet reached these levels.

Due to the severe wind erosion at the southwestern edge of the tel (Area A3), no remains later than the Hellenistic period were found. Three levels of the Persian period were excavated, but the two uppermost were not well preserved. In the lowest Persian level, we uncovered a rectangular room (3.50 x 4.25 m.), belonging to a large building which has not yet been completely uncovered. Its walls, preserved to a height of 1.5 m., are built of medium-size sandstones, between which beach-rocks were laid intermittently. The average thickness of the walls is about 1 meter. Built against the southwestern corner of the room was a silo containing two complete storage jars and several fragmentary jars; in fact, the floor of the room was completely covered with such jar sherds, indicating that this was a storage room. The eastern wall of the building adjoined a 3-meter thick retaining wall intended to support the buildings here, but much of it has fallen down the slopes.

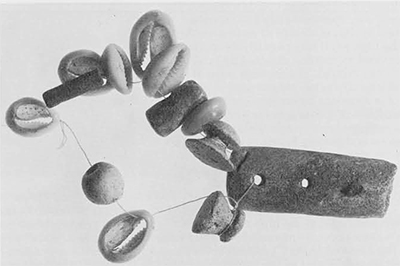

The Persian strata were separated from the underlying Iron Age level by a dirt-andash layer; in the Iron Age debris were found an iron knife or sickle blade and a 10th century B.C. jug decorated with black bands; inside the jug was a necklace with alternating faience beads, shells and worked bone pieces. A small probe was dug under the Persian retaining wall revealing sloping layers of ash and terra rose, the upper layer containing a storage jar and irregularly red-burnished sherds of the 10th century B.C.; underneath there was a layer of stone debris covering an ash layer which contained Late Bronze Age sherds, including fragments of bichrome ware and Cypriote “milk bowls.”

The lower mounds: The upper stratum of the southernmost mound (Area B) is dated to the Persian period. Two rectangular structures belonging to this period were found at the east and west of the mound, both built of small sandstones, their walls about 50 cm. thick. South of these buildings there was apparently a large, open courtyard. The two buildings were erected on older foundations dating to the Iron Age; in one of them a black juglet of the 10th-9th centuries B.C. was found. A probe was dug to a depth of about two meters under the Iron Age remains, but only sterile sand was found.

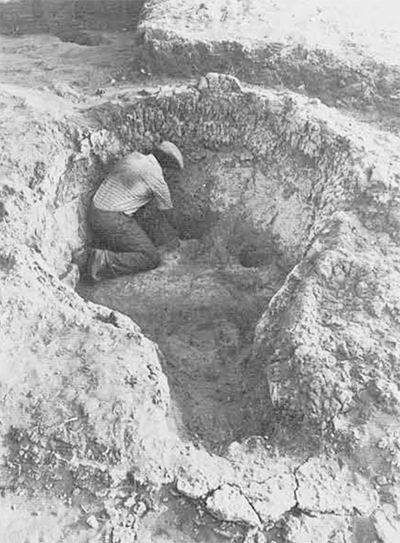

In the southeastern mound (Area C) five strata were in evidence, yielding a range of occupation from the Arabic period to the 10th century B.C. In the Hellenistic level—due to its close proximity to the surface—only an oval silo was discovered; it was built of several layers of clay, fired repeatedly to make it less permeable. About three meters north of this silo, a broken juglet was found containing a cache of 47 silver tetradrachms. It seems that this juglet was originally hidden under the floor, which had been washed away and later covered by the shifting sands. The coins were identified by Arieh Kindler, Director of the Kadman Numismatic Museum of Tel Aviv, as dating to the reigns of Ptolemy I-III, the majority (30 specimens) belonging to Ptolemy II (304-285 B.C.), while there were only 10 coins of his predecessor Ptolemy I and 7 of his successor Ptolemy III. The range of the coins in this hoard is from about 304 to 242 B.C., according to Kindler, and the percentage of coins issued by each of the three rulers points to a date of about 240 B.C. for burying the hoard, i.e. close to the last dated coin of Ptolemy III (Ptolemais, year 5 =242 B.C.). Ten of the coins were struck in either Egypt or Cyrenaica, but the majority come from the Ptolemaic mints of Phoenicia and Palestine; Sidon, Tyre, Joppe and Gaza; several are from Cyprus and one bears a monogram and a bee, pointing clearly to the city of Ephesus as its mint.

From the Persian stratum a plastered wall and installation were uncovered and at its southwest two narrow plastered and tiled drainage channels. Underneath were remains of stone foundations of a building partly paved with flat stones; a few Iron Age sherds found around the building date this stratum to the 8th century B.C. In the northern part of the area under the Persian remains, complete pottery vessels, including several chalices, were found “floating” in the sand at two levels, having no connection with any floor. The pottery dates to the 10th century B.C. Similar vessels found by Avigad in the northern mound were considered by him to be evidence of an open “High Place”.

The industrial district: On the southwestern slopes of the northern hill, we noted even prior to the excavations numerous lumps of burnt clay resembling slag. Upon clearing the area (F), we uncovered two clay kilns from which these vitrified pieces had broken off. Although we assume they were pottery kilns, they were not sufficiently well preserved to determine their operating process. Nothing was found inside them but ashes mixed with a few Persian sherds. In a trial dig through a thick ash layer further north, we found a conical seal depicting a griffin in neoBabylonian style.

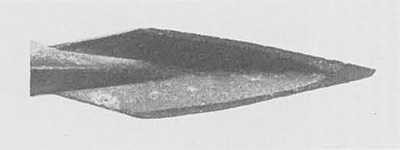

The cemetery: Located on the northeast part of the northern hill (Area E), the cemetery contained several types of burials of the Persian period: tombs lined with well-cut kurkar, tombs of softer sandstone, a pithos child-burial, clay tombs and simple inhumations. Burial offerings included a beautiful bronze bowl, bronze bracelets, Scythian-type arrowheads and a Persian amphora with a figurine impressed on its handle. In order to determine the lodation of the rest of the cemetery, a D.C. resistivity measurement survey was undertaken by Prof. A. Ginzburg of the Department of Geophysics and Planetary Sciences.

The “lower city”: On the east side of the northern hill, a section was cut (Area D), revealing a Persian occupation level; however, the major discovery here was a terra pisé rampart covered with a stone glacis. From the aerial photograph it is possible to trace the contours of these fortifications enclosing what we have chosen to call—at this stage at least—the “lower city,” an area of some 10,000 square meters. A few sherds of Middle Bronze Age IIB may indicate the date of the glacis. An Egyptian seal impression picked up on the surface of the tel bears the prenomen of the 12th dynasty ruler Amenemhet III; this seal impression could be evidence for the dating of the earliest settlement at Tel Michel as early as the 19th century B.C., but since the name of this ruler—in particular—was used on amulets and talismans sometimes even centuries after his death, we shall have to wait for the results of further excavations before attempting to date the beginning of the first settlement here.

- Neo-Babylonian style seal bearing winged sphinx

- Child burial in a jar. Persian period cemetery

- Aerial photograph of Area D, the “lower city, ” showing possible course of fortification wall

- (Left to right): Ze’ev Herzog, Ora Negbi, Anson F. Rainey, Shmuel Moshkowitz