Museum Object Number: MS 3428

Some rare evidence for social change in ancient Etruria reposes in the Penn Museum’s Mediterranean Section, in two large ovoid urns inscribed with Etruscan names. Even empty, the vases tell an unusual story about life in Etruria during the Roman takeover (ca. 350-100 BC). The Iron Age tradition of using the family’s water jars for burials was a comforting reminder of the way ancestors had lived. Both pottery shape and the incised lettering on the urns may be traced to 2nd to early 1st century BC Tarquinia, the great maritime city north of Rome. The names on the vases tell us more. The inscriptions read caes∙v∙v∙telmu (“Vel Caes Telmu, freedman of Vel”) and petrui telmus (“Petrui [wife] of Telmu”).

Caes is the Etruscan version of an old Latin name, Gaius, and V. stands for Vel, a favorite Etruscan given name. The formula V.V.—an abbreviation of Vel Velus or “Vel, son of Vel”—is similar to the Roman formula for manumission, or the freeing of one’s slaves. The freed slave took his master’s name and received a business, farm, or other type of investment to sustain himself and his future family. In Roman law (patterned on Etruscan law) the freed person had limited civil rights, but his or her children would be citizens. One hotly disputed right was legal marriage with free-born citizens. In some cities, freed persons could co-habit, but their children could not inherit the family’s hard-earned property. In 264/3 BC, Volsinii (the modern city of Orvieto) was destroyed by a war over these rights.

The former slave Vel Caes imitated the gentry by creating for himself a new family name, “Telmu,” formed from his old Greek slave name. Etruscan language does not use the letter “O,” so the famous Greek name Telamon (father of the strongman Ajax and uncle of Achilles) was changed to Telmu. One may wonder if this was a deliberate choice of name for a brawny slave of Greek origin. If so, Telmu’s hard physical labor clearly paid off in his freedom.

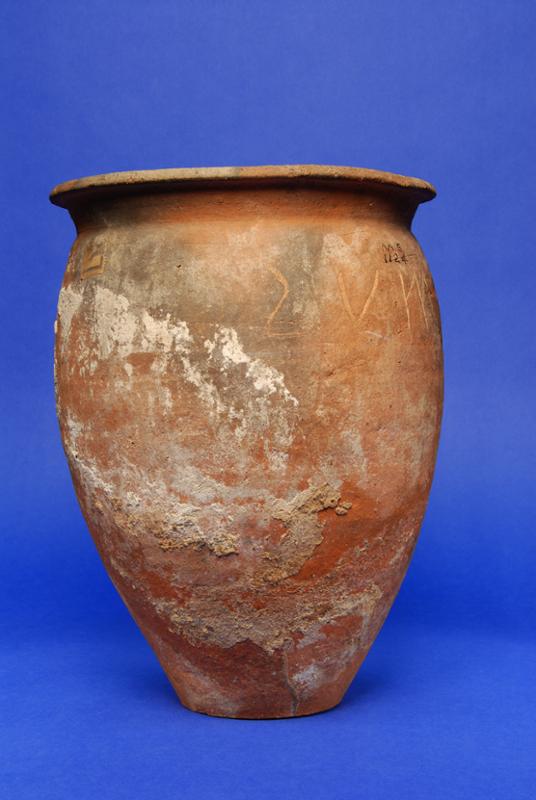

Museum Object Number: MS 1124

Museum Object Number: MS 1124

The second urn has a shorter inscription, an abbreviation completed as Petrui Telmus puia or “Petrui, Telmu’s wife.” This Etruscan woman took her husband’s new surname, at a time when aristocratic women usually added their husband’s name to their maiden name. Presumably Petrui was a commoner who had not used a surname before. If she had been enslaved, we would expect to see her master’s name: “Petrui, freedwoman of X, wife of Y.” There is no record of any slave or freedwoman called Petrui appearing in epitaphs, so our Petrui was likely a freeborn Etruscan woman who married a former slave. The couple’s urns are not the random acquisitions of poor people. Also, the “occupants” of the urns—and the children who buried them—were literate, thus a cut above the ordinary. So we may assume that Telmu and Petrui had succeeded in life and were not embarrassed by Telmu’s original entry into Etruscan society as a slave. After all, with the wars in Italy and Rome’s foreign conquests, thousands of people must have seen their lives change dramatically during this time.

Another curious condition has been preserved: when man and wife were cremated and buried, each vase was wrapped in cloth that was pulled over the rim, then tucked inside and tamped in place with a bowl sealed with a coating of lime. The patterns of the folds and fibers of the cloth are replicated in raised patterns on the surfaces. Only slight discoloration remains on Telmu’s urn, which was scrubbed vigorously by a 19th century dealer. Petrui’s urn bears ample traces of a mineralized textile: a fossil-like deposit that preserves the form of disintegrated cloth, in this case a simple cover or a garment woven of finely spun thread of linen or wool.

During the Iron Age (8th to 7th centuries BC), as Etruscan society grew stratified—with ruling elite, urban common classes, and slaves—citizens were often buried in urns that were “dressed” with helmets, clothing, or jewelry. The family of Telmu and Petrui, the former slave and his freeborn Etruscan wife, seems to have emulated the tradition of their betters in dressing the urns for their final rest.