Guatemala, when thought of archaeologically, usually recalls rainforests and the ruined temples and palaces of a Piedras Negras or a Tikal. For the most part we think of the lowlands of the great Department of El Peten, well to the north of Guatemala City, and of the fabulous ruins that cover so much of the low limestone plateau of that region. Yet the volcanic highland region, in which the capital city is located, is one of equally extraordinary prehistory. With the exception of the suite of Zaculeu in Huehuetenango (restored by the United Fruit Company), few ruins are ever seen by visitors, much less trumpeted by tourist bureaus and the like. Travelers in the Guatemala Highlands see the fountains and the other Colonial splendors of Antigua, the Sunday markets of Chichicastenango, and, of course, Lake Atitlan—and then leave to fly to Tikal, or to Copan in Honduras, without ever realizing what is archaeologically accessible in Guatemala City.

Iximche, the ancient fortress capital of the Highland Maya-speaking Cakchiquel people, is but an hour and a half drive from Guatemala City. Located in the Department of Chimaltenango, the site is about one and a half miles south of Tecpan Guatemala, itself a few minutes off the Pan American Highway. At an altitude of 7,000 feet, Iximche is spread out over a high plateau surrounded by ravines and pine-forested hills that dominate this part of Guatemala.

The name of the country, Guatemala., derives from Tecpan Cuauhtemallan, the pre-Conquest Mexican name for the site of Iximche. At the time of the Conquest, Iximche became the site of the first City of Santiago as capital of the country. (The old name survives in the nearby town of Tecpan Guatemala, which lives quietly today, and which was founded shortly after the final pacification of the Highlands.) Iximche itself was soon abandoned because of war; the new capital of Santiago —la muy noble y muy leal Ciudad de Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala—was founded in the Valley of Almolonga in 1527, by Jorge Alvarado, close to what is now known as Ciudad Vieja. An earthquake and eruption of the Volcano of Agua in 1541 forced another move to what is now Antigua Guatemala. The earthquake of 1773 caused the final move to the present modern City of Guatemala (the fourth location of the capital), less than three hours by jet south of New Orleans.

Iximche, now partially excavated and restored, offers us a rarely equalled opportunity to study conditions of Maya Highland life just prior to the Spanish Conquest and to link Maya archaeology directly to Spanish historical description. Iximche was what is called a “contact site,” and it was brought to an end by the Conquistadores, led there by Pedro de Alvarado as Captain General of Hernan Cortes, in the name of Charles V.

What We Know From Written Records

The mounds of Iximche have long been known. In 1840, the site was visited by John Lloyd Stephens, the pioneer Maya explorer. Later it was rapidly mapped by Alfred P. Maudslay. But what the site and its people once had been is best recorded in The Annals of the Cakchiquels. Written by the descendants of the Iximche nobles in their Cakchiquel-Maya language, this manuscript dates from the 16th century and was found in Solola near Lake Atitlan. Various published translations exist today. The manuscript was acquired by Daniel G. Brinton of West Chester, Pennsylvania in 1884 and eventually came to the University Museum in his important library of Americana. The document records the historical background of the large, militant Cakchiquel nation of which there are today some 300,000 descendants. Other native documents bearing on Iximche and these people also exist. Colonial records, for example the letters of Alvarado to his superior, Cortes, and from Cortes to Charles V, offer us further, though regrettably brief information. The first historian of the 16th century to visit the site was Bernal Diaz del Castillo. Fuentes y Guzman in about 1690 saw the then ruined Iximche and has left us an excellent description of its extent and composition. What do all these documents tell us?

Pedro Alvarado, who, after burning and razing Utatlan, the capital of the neighboring Quiche people, arrived with his army at Iximche in April 1524, left us the following account.

“I have left the city of Ublatan [i.e. Utatlan and I have come in two days to this city of Guatemala [i.e. Iximche] where I have been very well received by its lords. It could have been no better in the house of our parents [for] we were so well provided of the necessities that we missed nothing…”

This was on April 14, 1524, the equivalent of 1 Hunahpu in the 260-daySacred Round, a ceremonial cycle common to most Mesoamerican peoples. The Annals record that “In truth, they [the Spaniards] inspired fear when they arrived. Their faces were strange. The lords took them for gods.” Alvarado was addressed by the nobles of Iximche as Tunatiuh, or sun, a Mexican appellative which Alvarado had been given because of his light complexion and which had preceded him from Mexico.

At that time the dual kings of Iximche were Belehe Qat and Cahi Imox. The latter was described as arriving to meet Alvarado “in his litter decorated with quetzal feathers and gold jewels, followed by the principals of his court. Alvarado dismounted [from his horse] to greet him with many tokens of courtesy.”

Two militaristic cultures, one New World, the other Old World, were meeting in Iximche, a confrontation with the same elements of wariness and courtly form shown by Cortes and Moctezuma II in their epochal fateful meeting in 1519 far away in the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, now Mexico City. Alvarado and the dual rulers of Iximche had their own political and strategic designs that could appear to be identical up to a point, but they were bound to conflict, and soon.

Among other things, in 1524, Alvarado insisted that the conciliatory Cakchiquel kings deliver to him one thousand gold leaves of fifteen pesos each. (Alvarado later denied in part the charge in the Spanish proceedings against him of being an excessive Conquistador.) Terrible persecutions by the Spanish against the rebellious Cakchiquels were common up to 1530 when they submitted to the Spanish tax. But there was still discontent. In 1540, just sixteen years after their first meeting, Cahi Imox was hanged by Alvarado in the belief that he was plotting new uprisings against the Spaniards. The Spaniards, too, had not always agreed among themselves. In 1526, a rebellious band had even fone so far as to set fire to Iximche.

From the Annals we know that Iximche had a most brief but violent history. It was founded around 1470 by the then dual rulers, Huntoh and Vukubatz. Prior to this the Cakchiquel people and the neighboring Quiche Maya were cooperative and peaceful, at least insofar as Highland political conditions permitted. Chiavar, which some speculate may have been ancient Chichicastenango, was the first capital of the Cakchiquels. It is recorded that the Quiche ruler, Qikab was dethroned by his sons. Qikab advised the Cakchiquels to leave Chiavar for their own safety. They then moved southeast to a mountain called Ratzamut. Here, they started to build their new capital, Iximche, and organized their defense. (The name Iximche, is the Cakchiquel term for the ramon tree, Brosimium alicastrum which is found in the area.) From then on, until the arrival of the incredibly efficient and confident Spaniards, war was endemic between the Quiches and the Cakchiquels, apparently to the advantage of the latter. Alvarado, like his superior in Mexico, Cortes, knew brilliantly how to take advantage of indigenous enmities.

Other Sources of Information

If documents help to clarify Iximche and the Cakchiquels of pre-contact times, so do the descendants of those people. Today the Cakchiquels occupy a territory approximately equal to that at the time of the Conquest. Many cultural items survive from the past. The Maya language, as a distinct dialect, is still used, though partly modified by Spanish infusion. The Sacred Round, or 260-day ceremonial cycle, persists and is used today by shamans and curers. This was the calendric cycle that gave the Cakchiquel kings their names, according to the numbered and named day on which they were born within the cycle

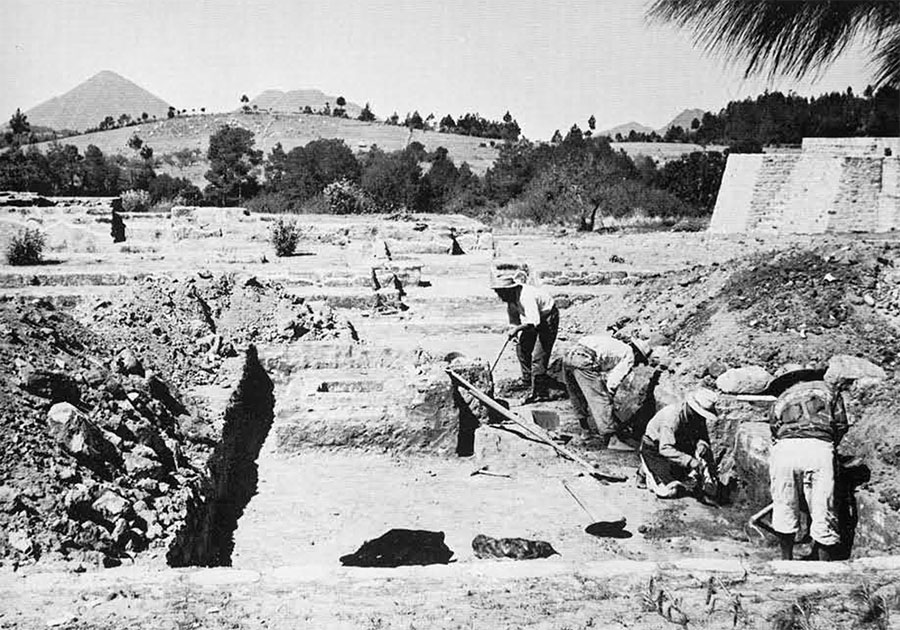

The modern study of the ruins of Iximche started with the work of Janos de Szecsy, an historian, who, with the backing of the Government of Guatemala, undertook excavations in January of 1956. Unfortunately his life ended that year in an air crash and work was suspended. After preliminary reconnaissance and mapping in 1958, I resumed the Iximche field work in September 1959. The excavations went on by seasons, with temporary interruptions. The Guatemalan Committee for Reconstruction of National Monuments underwrote the costs of field work until July 1961. As of 1963, excavations were sustained by a generous grant from the Swiss National Foundation for Scientific Research. The Iximche Project has continually benefitted from the collaboration and contact with the Institute of Anthropology and History of Guatemala; the never failing support of Lic. David Vela has been vital throughout.

Iximche as Described By Early Visitors

Turning specifically to the site of Iximche, the visit by Fuentes y Guzman about 1690 provides us with important data. Recinos has summarized his words as followed:

“…the city covered a plain three miles long from north to south and two miles from east to west, which could be entered only through a very narrow causeway which was closed off by two doors of obsidian stone. The ground was covered by a thick layer of mortar. At one end could be seen the ruins of a magnificent building [possibly Structure 2], perfectly square, each side one hundred paces long, made of well-cut stone masonry. In front of this building extended a large square, on the sides of which might be seen traces of a sumptuous palace. Old fountains of houses could be seen surrounding the ceremonial center.

The city was divided by a moat three yards deep, which ran from north to south and had battlements of rough stone and mortar more than a yard high. On the eastern side of the moat were the houses of the nobles and on the western side those of the common people. The streets were wide and straight. To the west could be seen a little hill which dominated the city, and on its summit might be observed the remains of a round building like the curbstone of a well…This was the place where judges tried civil and criminal cases…”

The moat observed by Fuentes y Guzman and later commented on by John Lloyd Stephens, is still visible but practically filled. Recent excavation has shown that its original depth was about 25 feet. It appears to have been intentionally filled soon after the Conquest in order to obliterate the city’s defenses. While the breastworks, or battlements, were still standing in 1840 on Stephens’ visit, today only a portion of the core remains. Its original height must have been over ten feet. The bridge noted by Fuentes y Guzman (and Juarros) figures dramatically in a revolt at Iximche in 1493 described in the native Annals:

“Then the attack on the city began at the end of the bridge, the place Chucuybatzin [a Tukuche general] had chosen for the battle and to lead the Tukuche [a branch of the Cakchiquels] to the revolt. Four women had armed themselves with cotton cloaks and with bows, disguised for the battle as four young warriors. The arrows launched by these fighters pierced the very mat [a symbol of authority] of Chucuybatzin. It was horrible, the great revolution of the lords of old.”

The description continues and is detailed enough to permit the reconstruction of action on the terrain of today.

As Bernal Diaz del Castillo came through Iximche in August 1526, he had to battle his way into the city, as Cakchiquel squadrons, hiding in the “ravine,” fought to keep the Spaniards from entering. This famed historian slept in the city and leaves us this description:

“The rooms and houses were as fine, and the buildings as luxurious as those indeed of chiefs who ruled all the neighboring provinces.”

This brief evaluation, from four centuries ago, is flattering insomuch as Bernal Diaz, the sophisticated observer had already been thoroughly awed by the splendors of Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital. Excavation has shown his impressions of Iximche to have been justified.

Iximche As Seen Today

Many structures are known to have been decorated with elaborate polychrome paintings, sometimes on stucco, sometimes on a fine clay facing applied to the adobe walls. The architecture of Iximche was indeed impressive, particularly in the generously spaced settings. The principal part of Iximche consists of four large plazas and two smaller ones. They occupy the highest part of the deliberately leveled plateau. The terrain here has been so heavily modified by ancient terracing, leveling, and construction that no natural surface survives. The ceremonial plazas are well marked and, although interdependent, they can be considered as forming separate groups. Plaza levels, groupings and, particularly, orientation differ markedly, yet these discrepancies appear to be responses to the variable terrain. Each plaza group has from one to three temple-style structures and a number of residential structures of palaces. Two groups have a ballcourt. Many small structures, of ceremonial use, cluster in these plazas. There are eleven of them in Plaza A alone. These large paved areas were drained by a light slope in the plaza floors. Cement-lined gutters were built at certain spots along their peripheries. By and large, the center of Iximche consists of the substructures of temples and the platforms of houses. The construction cores of these substructures comprise, for the most part, rough stones in a clay matrix. The outer faces of these structures were made of solid stone blocks laid in mortar and covered with a lime cement facing. The buildings that rested on these substructures were made of adobe. The adobe walls and columns carried roofs of pole-and-thatch. A major fire is recorded in the Annals on a day equivalent to January 1, 1514. And, as noted, the Spaniards burned the city once again in 1526.

The Excavation of Iximche

Excavation has shown Plaza A, the larges, to contain a ballcourt (Structure 8), two temple-type buildings (Structures 2 and 3) and ten palace-type platforms, five of which contact each other. One of the best preserved palaces at the site, Structure 22, consists of a long raised rectangular building with interior benches along three sides of the single room, with circular fireplaces sunk into the room floor, and with five adjacent doorways separated by piers.

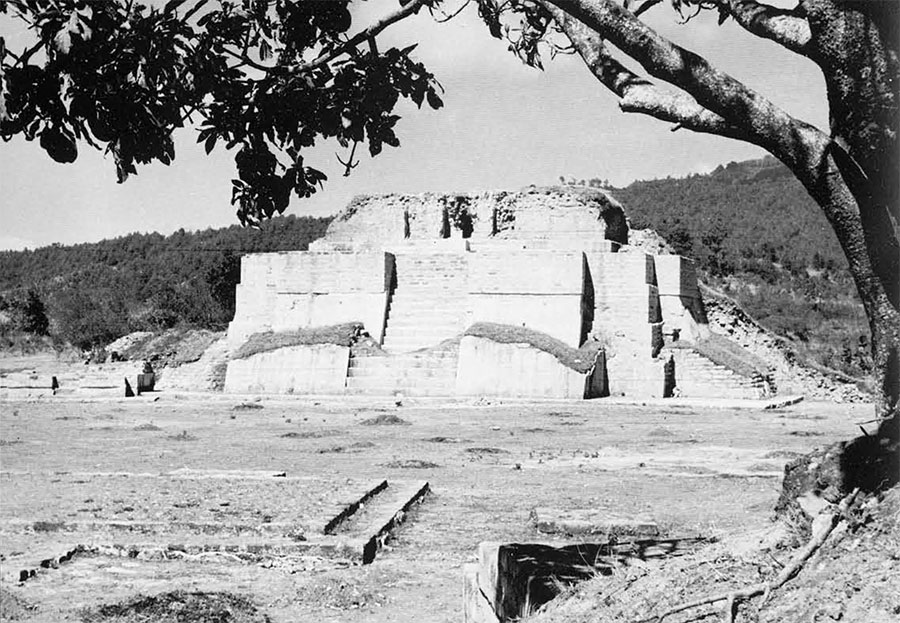

The great temple, Structure 2, dominates Plaza A. It is on the west side of the plaza, across from its probable twin, Structure 3. Excavation, particularly by tunneling, has shown Structure 2 to consist of three superimposed temple-type constructions. The earliest temple is barely known beyond the fact that it was almost obliterated in preparation for building the intermediate structure. Erosion of the final temple exposed some of the intact masonry of the intermediate structure. The final construction suffered greatly from the extraction and transportation of its cut stone masonry which was re-used at nearby Tecpan. This final temple was the one in use at the time of Alvarado’s ultimately disastrous visit. A steep stairway ascends the terraced substructure. Close to the edge of the top of the pyramid, at the head of the stairway, is a small masonry altar provided with a slightly concave block of plastered stone, which was most certainly used for human sacrifice. The three doorways of the temple itself enter on a large room. Two room floors occur in the final phase, an original one and a later resurfacing. Cut into the earlier floor was a pit, apparently intended for a burial; but something intervened and the pit was refilled and the floor resurfaced. This perplexing feature may reflect the recorded epidemic of 1521. The Annals woefully tell us: “Great was the stench of the dead. After our fathers and grandfathers succumbed, half of the people fled on the fields. The dogs and vultures devoured the bodies. The mortality was terrible.” Cached just in front of the building were the remains of a turtle, another interpretative puzzle!

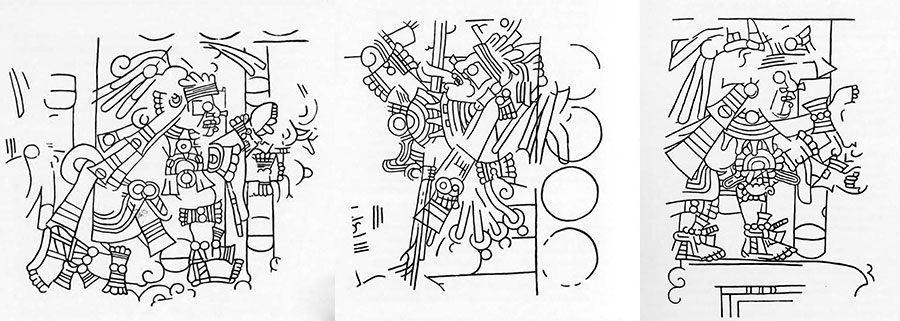

The walls and doorway piers of Structure 2 show vestiges of once splendid polychromed paintings. These were blocked out by a pointed object on a clay base. Red, yellow, and blue were employed. There are ten related paintings, surely the work of a specialized artist. Repeated in varying attitudes is a human figure. In one case he performs a blood sacrifice involving his tongue. The style employed suggests a relationship with Mixtecan pictorial expression known from Mexico in the few centuries preceding the Conquest. Regrettably the condition of these paintings is poor, due to leaching and root action; therefore, only a small portion of them could be properly removed and preserved.

The interior of the temple has benches on three sides and a circular, sunken fireplace in the center of the room. The rear wall is broken by a central doorway leading into a small shrine-like room. The total height of the final structure must have been close to fifty feet.

Structure 3, the temple across from Plaza A from Structure 2, produced in excavation a large quantity of fragments of large cylindrical incense burners. These were found scattered over a plaza floor about the structure. Surely as many as a dozen censers were in use in the temple above. The modeled appliqued figures on them were different from any seen before. One design, repeated on several censers, is conceivably the sun disc suspended from a sky-band (the whole reminiscent of the Mexican ollin symbol). Curiously, widely scattered about the temple base were fragments of a vase of plumbate ware. This ware is highly distinctive and the type found is a hallmark of the early Post-Classic period throughout much of Mesoamerica, that is, A.D. 900-1200. Since Iximche was not founded until 1470, we can only conclude that this vase was a relic kept in a temple sanctuary, possibly that of Structure 3. Conceivably this piece of plumbate was looted from Zaculeu, the religious center of the Mam people to the northwest, which flourished during plumbate times (burials with plumbate vessels have been found there). The Cakchiquels, with their pre-Iximche military partners, the Quiches, are known to have successfully warred against the Mam at Zaculeu; the two Cakchiquel leaders who fought at Zaculeu are precisely those who founded Iximche.

The luxuriousness of elite residence at Iximche is exemplified in the “Great Palace,” a huge residential compound that grew by accretion on the northeast side of Plaza B. This compound was found to comprise various stages of rebuilding. The earliest stage surely dates back to the foundation of Iximche. It consists of four residences facing onto a quadrangular patio with a masonry altar-platform in its center. The interiors of these elaborate houses have built-in benches along the walls and, additionally, fireplaces sunk into the room floors. The doorways, as in Structure 22, are separated by adobe piers. The adobe walls were originally painted and decorated, but practically all traces are now gone since the walls were almost obliterated prior to rebuilding the compound. The plan of these buildings indicates that they were in fact houses. This is confirmed by the presence in the associated rubble of grinding stones, obsidian knives, griddles for baking tortillas, kitchen vessels, and other utilitarian items. The central altar, however, indicates the extent to which religion entered the lives of those living about the patio. Moreover, many fragments of ladle incense burners were recovered from about the altar. From an original size of some five hundred square yards, this compound rapidly grew in the following decades, outwards, and upwards as well, with the addition of new residential units with enclosed patios. The final stage of construction of the Great Palace may fairly safely be attributed to the dual reign of Hunig and Lahuh Noh, that is, 1508-1521. By this time the multi-structured palace occupied an area of over four thousand square yards. Everything indicates that Iximche architecturally mushroomed to its final extent in some fifty years.

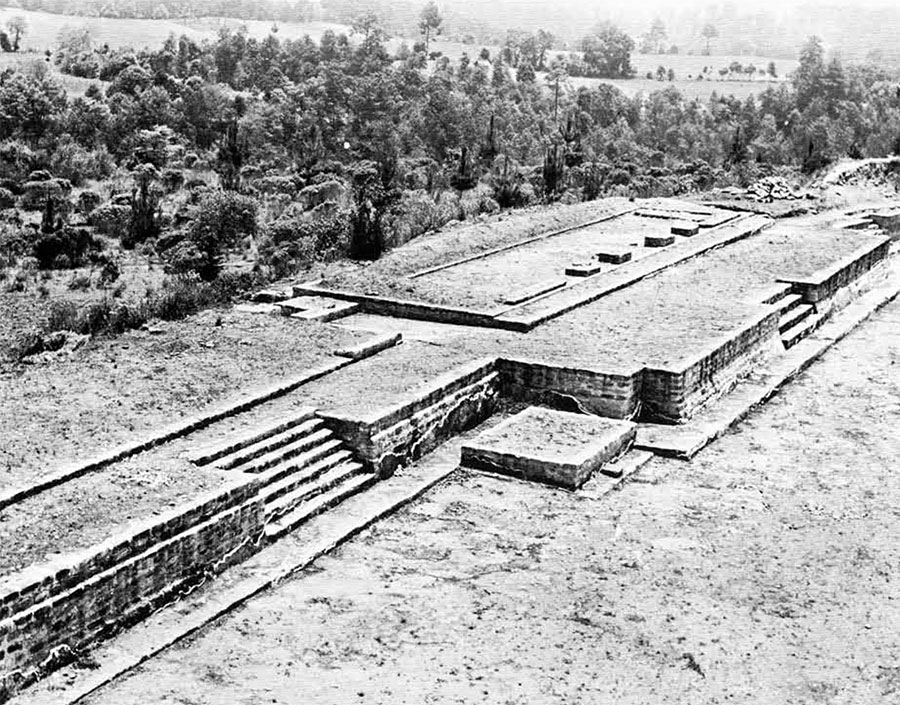

One of the two ballcourts, Structure 8, has been excavated and stabilized (as have been all major excavated structures). This court features enclosed masonry ends, or end zones. The playing area is about 100 feet long and, between the high parallel benches, is 23 feet wide. The total length of the construction is 130 feet. Two coats of plaster have been found in the court, suggesting that it was constructed in the middle of the local sequence, possibly about A.D. 1500. The other ballcourt, Structure 7, may be somewhat older; in any case it is difficult to imagine the lords of Iximche doing without the deep-rooted institution of the ball game. No stone markers were found in either the court or up on the high benches in Structure 8. But two tenoned zoomorphic stone sculptures had been abandoned close to a nearby structure in modern times. These may have been markers or goals on the benches and perhaps the same that Stephens describes from his 1840 visit as very much weathered. To me they appear to have been crudely carved rather than severely eroded jaguar heads which were finished off by finely modeled stucco, since destroyed.

The Plaza C group is unique in being isolated from the adjacent Plaza B group by 3-foot thick stone walls which impede direct communication between the two. The purpose of this obstacle eludes us. The whole northeast side of Plaza C is occupied by Structure 38, a 200-foot long platform sustaining three houses, each provided with its own stair. Ceramics found within these houses are predominantly domestic. Associated ceremonial pottery includes a broken effigy censer representing Tlaloc, the widely revered Mexican rain deity. Temple Structure 5 was partly excavated and shows at least two construction phases. Although the substructure, or pyramid, has a single central stair, the final access to the actual temple consists of a double stair. The southwest portion of Plaza C has been discovered to be bordered by house structures that faced not onto the plaza but away onto a previously unmapped court. This adjacent court is surrounded by six house platforms as well as temple Structure 6. Three exterior sides of the nearby ballcourt, Structure 7, have been exposed to date. Projecting stairs occur at both enclosed ends while there is an additional stair at te southeast corner of the east part of this ballcourt, the second one known at Iximche. A marker in the form of a human head with a tenon was found elsewhere in Plaza C but may pertain to the ballcourt.

Human Burial And Sacrifice

A remarkable find occurred immediately west of Structure 4. Close to ten square yards here had been paved with human skulls. The presence of cervical vertebrae indicated decapitation. These skulls may represent a ritual offering since most of the forty-eight skulls were accompanied by obsidian blades. A number of the skulls had been buried in small lots but the remainder had been set individually in pits cut into the plaza floor.

Further evidence for human sacrifice is also found at Iximche. The altar and stone block on Structure 2, already cited, indicate that a common way of performing human sacrifice was heart removal; a notched flint knife suitable for use in human sacrifice has also been recovered. An offering of two severed skulls was found southeast of Temple 2, cached along with obsidian knives. Human bones were used to make musical instruments, here a pentatonic flute and a multiply-notched rasper bone. Structure 14, a circular masonry altar in Plaza B, with a diameter of twelve feet, is similar to altars used by the Aztecs in the “gladiator sacrifice.” Secondary individuals in an important burial also point to human immolation.

The burials discovered to date at Iximche had been intruded beneath house or palace platforms. The buried individuals are usually in seated position, with no standard orientation. Usually a broken obsidian point is found with the dead. In one case a woman was found with her smoke-blackened cooking pots. A child was found with a jade bead, while one old man was oddly provided with charcoal.

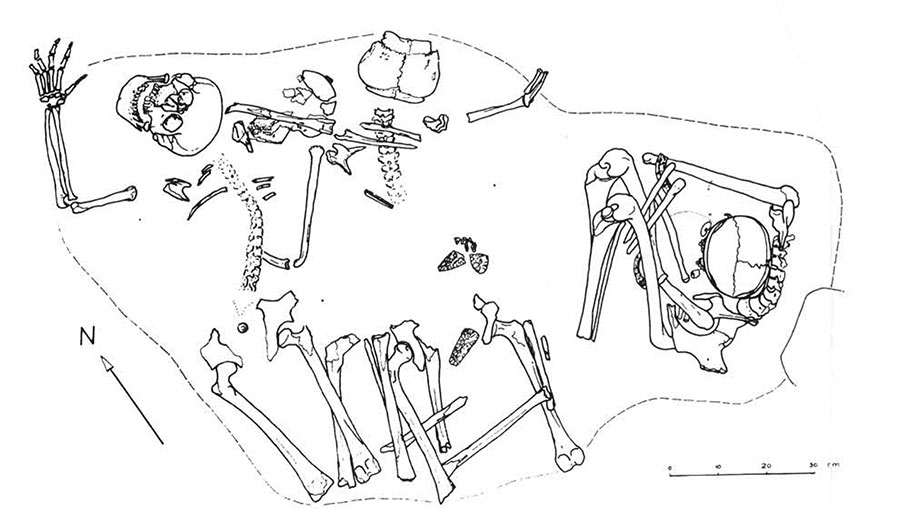

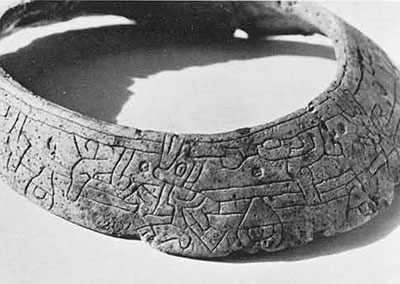

The most elaborate burial yet discovered, in Structure 27, behind Structure 2, consisted of four individuals. The main occupant of this grave (Burial 27-A) wore a headband of gold and a necklace of ten gold jaguar heads as well as forty small gold beads. At the elbows were bracelets carved from a human skull. These bracelets were delicately incised, showing repeated birds and stellar symbols hanging from a “sky band.” A finely carved jade object was found near the jaw. Originally it may have been placed in the mouth, a fairly common feature in funeral ceremonies among many Mesoamerican people. This individual, with evidence of cranial damage, surely a mortal would, was accompanied by three others, the group of four having been crammed into an area little more than two square yards. In the absence of proof, my own feeling is that the principal of this burial may have been one of the sons of King Vukubatz who was one of the two founders of Iximche, both of whom were killed in battle while trying to expand the Cakchiquel province. At Iximche there is every incentive to try to relate interments and construction directly to individuals since their reigns and achievements are recorded, however briefly and enigmatically, in the Annals of the Cakchiquels.

Can Buildings Be Identified With Historical Personnages?

With this in mind I would like to point out certain possibilities. For instance, as many as three successive superimposed plaster floors comprise the plazas so far investigated, a fact which incidentally confirms the observation of lime-mortar flooring by Fuentes y Guzman around 1690. The historian, Martin Alfonso Tovilla, writing early in the 17th century, visited the neighboring Quiche capital of Utatlan, then abandoned. Tovilla on this trip was accompanied by a grandson of the native ruler of the Quiche province, who informed him that, anciently, “When a king died, lime [plaster] was applied to all the streets and to the inside and outside of palaces and new histories were painted.” Given the close relationship (alternately amicable and warlike) of the Quiches and the Cakchiquels, this practice of renovation and rebuilding ought to apply equally to Iximche. Both Utatlan and Iximche have written records indicating successions to power which closely parallel the number of plaster coatings found in floors and buildings. Further study in this matter should be rewarding.

Moreover, the Annals make clear that four dual kingships span the occupation of Iximche. Huntoh and Vukubatz founded Iximche. These two rulers were succeeded on their deaths by, respectively, their eldest sons, Lahuh Ah and Oxlahuh Tzii. Lahuh Ah was the first to die ad was succeeded by his oldest son, Cablahuh Tihax, who co-ruled with Oxlahuh Tzii. The latter died in 1508 and his rule passed to his eldest son, Hunyg, while Cablahuh Tihax died a year later, in 1509; his successor was his eldest son, Lahuh Noh, who thus became a joint ruler with Hunyg. Both Lahuh Noh and Hunyg died in 1521. Direct father-to-son dynastic inheritance of rulership was at that time evidently subordinated to a council decision, for we read that in 1521 the successors, Cahi Imox and Belehe Qat, were elected or confirmed. It may be assumed that the Iximche temples and related structures were the property of the joint rulers, whose titles were “Ahpoxahil” and “Ahpozotzil.” These titles carried equal weight, and each simply reflects descent from one of two groups with a common root.

No archaeologist could work at Iximche without wondering whether, say, Plaza A pertained to Vukubatz and his descendants or to Huntoh and his lineage. Obviously the first step is to search for further evidence of coordinating rebuilding within a plaza without necessary rebuilding in an adjoining plaza. A second step would be to discover more tombs of important individuals who might be shown, on analysis, to relate to the dynasties outlined in the Annals. Close attention to skeletal material might aid in this study.

If excavations to date have failed to resurrect the famed kings and lordly sons of Iximche, neither have they shown that the Spanish conquered it. The striking fact is that were it not for the cited documents, the only evidence that Europeans were once present at the site is a few wrought-iron cross-bow darts found on or close to the surface!

More Questions

The significance of this site blooming so late within the complex turbulent times of Highland Guatemala just prior to the Conquest is easily inferred from the feudal ways of life described in still little-known Quiche and Cakchiquel documents and Colonial chronicles. But while many problems of Iximche history can be readily solved through the analysis of native documents, there are other questions that only further excavation can answer. Iximche has been constantly referred to as a city, and a fortified one; biut was it really a city or actually only a ceremonial center? Did its social and economic makeup really qualify it as a city as defined by William A. Haviland in his discussion of Tikal in the Spring of 1964 number of Expedition? Were there markets? Was anything manufactured? Who live in Iximche—just priestly families and their retinues, or also farmers, potters, tradesmen, soldiers? What was the social organization? What was the population density? Archaeological work so far indicates that Iximche really was a city, but much excavation and study are needed before we can attempt to answer all of the questions posed.