Just over a century ago white men in sailing ships began to carry off young Solomon Islanders from the coasts of the island of Malaita, to work in the sugar plantations of Australia and Fiji. Many never returned. For fifty years after that, no white man was safe ashore along the Malaitan coast without armed guard, though British government and missionaries found a few precarious footholds. The most feared Malaitans were the Kwaio of the central mountains: they had attacked two recruiting ships in the 1880’s, massacring their crews to avenge relatives lost in Queensland; they had killed a missionary in 1911; and as late as 1927, when the government tried to impose the Pax Britannica and taxation, the Kwaio wiped out two British officers and their party.

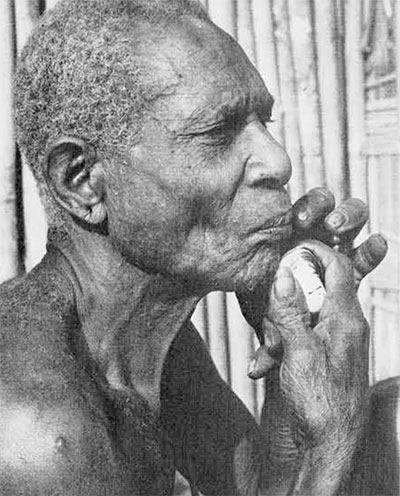

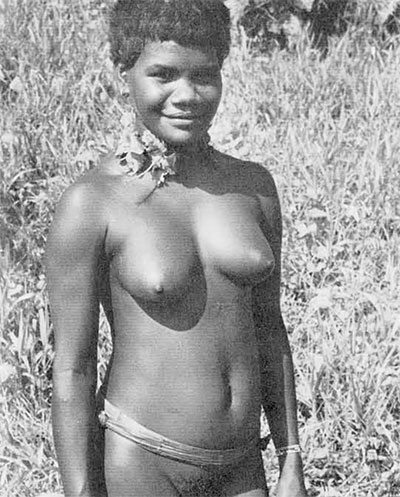

When I first penetrated the jungle-clad mountains of Kwaio territory in 1962, I found that Kwaio life had remained surprisingly unchanged in the intervening decades, despite sixty years of mission and government efforts, and despite the impact of World War II on the Solomons. Pagan priests sacrificed pigs to their ancestors, girls and women were nude in customary fashion, the high points of social life were elaborate mortuary feasts using strung shell beads as valuables. and subsistence still depended on shifting cultivation of taro and yams. Steel knives and axes, and the ubiquitous pipes, were the only striking signs of change. Kwaio remained committed, proudly and even defiantly, to the ways of their forefathers—though almost all Kwaio men had seen, during their terms as plantation laborers, glimpses of a modern world which they chose to reject. Even the British-imposed domestic peace has been somewhat tenuous: sporadic killings still take place, and in 1965 a Seventh Day Adventist missionary was speared to death by an unknown Kwaio assailant.

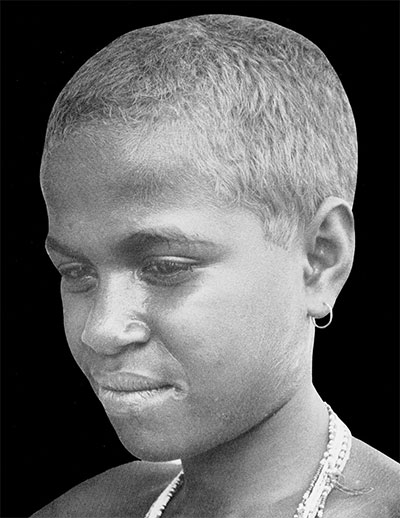

(the sister of #5 on this page).

My Kwaio research has been shaped by the anachronism of these tribesmen, surrounded by a world of airplanes. cars and transistor radios, yet still sacrificing pigs to their ancestors. Like the anthropologists of earlier decades, I faced in my isolated jungle base the staggeringly presumptuous task of learning and analyzing singlehandedly the whole of a way of life radically different from my own—of studying with technical competence everything from art, botany, cosmology, demography and ecology on to zoology. But in the 1960’s, with an increasingly specialized and sophisticated anthropology and with the technology of modern tape recorders, jet mail service and computers, I could try to record and analyze an old kind of anthropological scene in new and more systematic ways.

A year and a half of field work yielded detailed records of social life in this jungle setting. including voluminous genealogies, residential histories and documentation of the intricate patterns of investment in feasting and bridewealth payments; and it brought fluency in the Kwaio language. These made possible the usual kind of modern anthropological analysis, here of a social system of unusual interest. But how could I penetrate deeper into this way of life to see it from the “inside”—in terms of the categories and models of the Kwaio themselves—rather than from the outside? And how could I see the processes and continuities and cycles of Kwaio social life from a narrow time slice” of less than two years?

A rare stroke of fortune was a collaboration that developed with Jonathan a Christian Kwaio tribesman who had worked with American troops during the war and had led his people in a pro-American, anti-government political movement after the war. On his own initiative, during my absence for a break in Australia, Fifi’i began in 1963 to record events and transactions among Kwaio pagans. Since then, for eight years, he has continued to compile a record of Kwaio social life almost unparalleled in anthropological richness: almost 3000 pages to date, documenting in his own language the feasts. quarrels. sacrifices, rituals and other events in the lives of his fellow tribesmen.

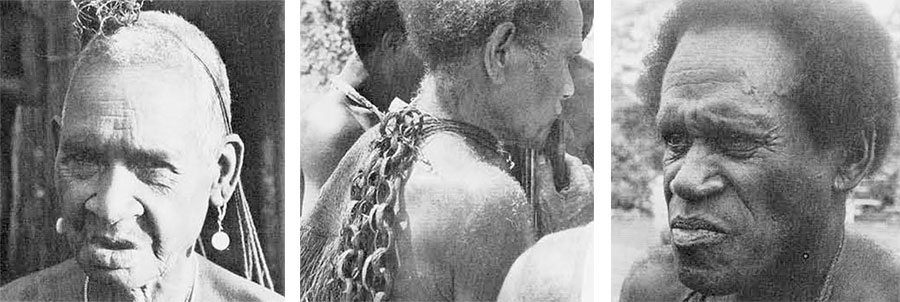

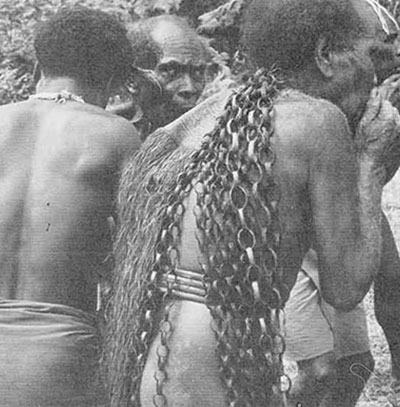

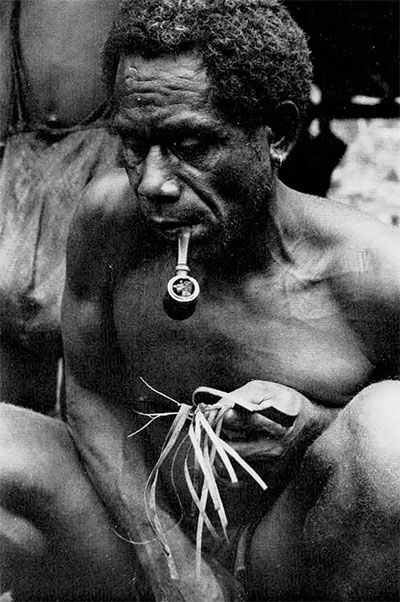

(Center) An old Kwaio warrior plays panpipes in a sacred dance.

This man took a prominent part in the 1927 massacre an spent many years in jail.

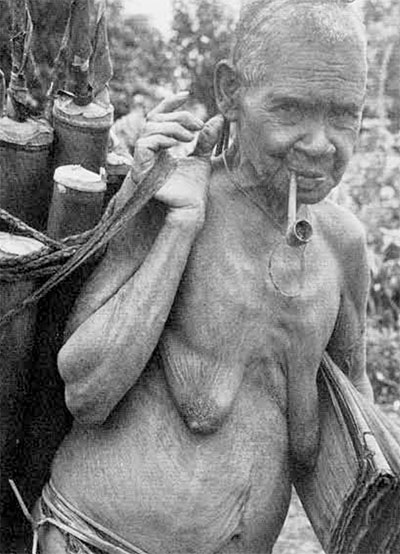

(Right) A Kwaio priest. This man’s whole family was wiped out by the punitive expedition following the massacre of a government party.

Our collaboration has now produced a continuous record of almost a decade of life among the Kwaio. The record of the continuities of social process extends further back as well: remembered details of hundreds of feasts given over several decades and a reconstruction of a household-by-household census as of October 4, 1927 —the day the District Officers were massacred. What usually appear in anthropological field work as isolated events and fragments now emerge as stages or episodes in unfolding cycles and processes: the transactions of a 1967 marriage reciprocate contributions to the bride’s father’s marriage thirty years earlier; a dispute about sacrifice in 1970 is simply the latest round in a quarrel between two men that began with a pig theft I recorded seven years earlier: a boy I first knew as a shiftless teenager has become a husband and father and has succeeded his father as a priest.

These continuities were further documented, and the mysteries of Kwaio symbolism and cosmology further explored, when my wife and I returned to Kwaio in 1969-70, this time accompanied by our own three young children. This, added to a short visit in 1966, brought the time spent with the Kwaio to three full years.

The richness of this ethnographic record has turned out to be a mixed blessing. How to avoid being deluged with data? How to pull together related events from thousands of pages of notes? How to analyze the tens of thousands of transactions in the complex webs of investment so as to find out how they are intertwined?

Here the electronic age—with the generous support of the National Science Foundation and the University of California—has enabled solutions anthropologists of the 1920’s and ’30’s could scarcely have dreamt of. Using a high-speed computer. genealogical relationships between any of some 5000 individuals, living and dead. can be traced: marriage and feasting transactions can be analyzed and the strands of their interrelationships can be unravelled. A Kwaio dictionary of some 15.000 words has been computerized. In 1970, in search of rare and unrecorded words, my student colleague, Nathan Smith. printed out by computer and sent to me in the field some 8000 new sequences of sounds that might conceivably be Kwaio word bases but had not been recorded —the ultimate “non-book.” About 400 of them turned out to be rare or archaic Kwaio words.

But the thousands of pages of field notes—describing ritual sequences, litigation, observations of daily life, and so on—could not be indexed and analyzed economically by computer. Much of this record is written in Kwaio; and in dealing with running text, even in English, the crucial problem is one of indexing—of finding what you want so you can read and analyze it. Here our solution has been the Kodak Miracode System. Documents are coded by subject, then microfilmed; the identifying code for each document is electronically imprinted on the film. Using a keyboard console, one can almost instantly hunt out and visually examine documents dealing with some desired combination of subjects.

It will take several years to dig out the evidence on tribal social life that can be gleaned from these rich Kwaio data. But fascinating perspectives have emerged already. Though these points of view are not revolutionarily new, the nature of Kwaio social organization and the depth of our data make them particularly compelling.

2. A priest talks to the ancestors in a shrine.

3. A Kwaio housewife empties the day’s garden produce for the evening meal.

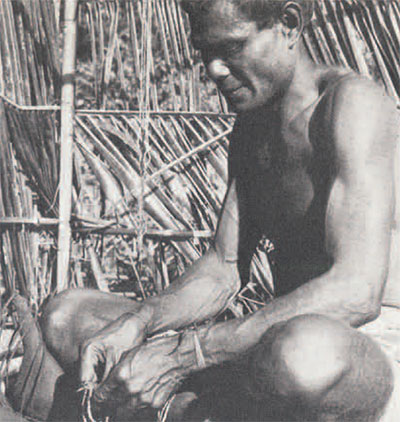

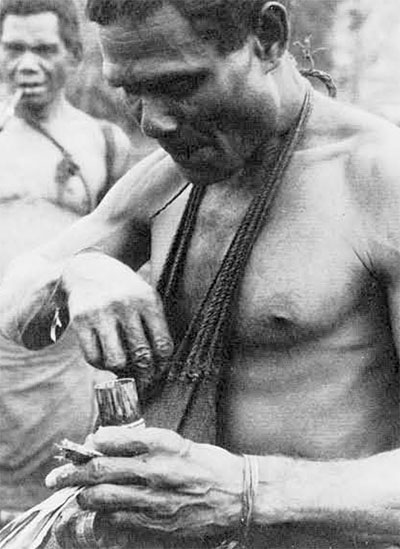

4. A feastgiver supervises the carving of pork portions for his guests, using strips torn on a leaf to keep track of the portions.

First, the variability and flux of Kwaio social groupings, with tiny settlements constantly moving and changing in membership, make many usual modes of anthropological description conspicuously inadequate. There is simply too much variation, and too much change, for us to describe an idealized or “typical” household or settlement or descent group. Nor are statistical summaries of who-lives-where-with-whom adequate to the task. Rather, I have had to seek out the implicit “rules of the game” whereby Kwaio make decisions and pursue strategies of social life. However varied Kwaio social groupings are, they represent the cumulative outcomes of strategies and choices. Though Kwaio cannot always tell me the “rules” for making appropriate choices, they emerge through long and careful probing and observation. One striking example will illustrate. Though most Kwaio households include a married couple and their children, I recorded one settlement of 14 people, living in five households, that included not one married couple—only a cluster of adult bachelors and spinsters and the children of deceased close relatives they were fostering. Yet this odd residence pattern represented the cumulative result of appropriate decisions made in the face of adversity. Uncovering the unstated, implicit rules for playing the games of social life promises to give increased powers of anthropological understanding—though we are still pioneering and experimenting with ways of discovering and describing these rules.

regular meal of the day.

Anthropologists often describe tribal societies as if they were, in effect, composed of a set of interlocking “pieces.” Each piece is a legal corporation, with membership determined by descent: a person belongs to the corporation of one of his parents (in most societies, that of his father). The corporations are then fitted together into a larger design by ties of marriage and webs of kinship. But such a mode of description, which seems superficially to fit Kwaio social organization, fits less and less well as one looks carefully through the voluminous records of real people doing things together. What is supposed to be a single group, one “piece” in the puzzle, turns out on closer inspection to include different people on different occasions in different settings. Rather than seeing Kwaio society as composed of a set of groups, it seems more revealing and realistic to think about individuals moving through the varying situations of social life—and, according to the particular context and the rules of the game appropriate to it, periodically crystallizing together into social groups. Again, looking at the rules of the game reveals more than looking at the varying outcomes of the game.

In fact, even talking about “rules of the game” introduces a convenient but dangerous simplification—for not all individuals play by the same rules. The difficulties of making generalizations that do not do violence to the Kwaio data, in all its depth, raise a disturbing doubt about what an anthropologist writes about another people’s ways of life: is it possible only because of his limited evidence and relative ignorance of how complicated and variable things really are? The anthropologist who can confidently write about “the lineage” in an African tribe would be hard-pressed to write in a similar vein about the department” in his university—because he knows too much.

The anthropologist who is fortunate enough to be able to spend three or four years in another society eventually finds that things seldom surprise him any more, that his intuitions mesh with those of his subjects, that he can live comfortably in another people’s world, with its tastes and smells and sounds, and its codes of language, gesture and etiquette. But then he discovers another problem. For he can write articles about their kinship system or residence rules or cosmology; but he cannot express in scholarly descriptions the more subtle elements of their culture he has absorbed by long immersion, by participation and empathetic involvement. As a human being he can learn what as a scientist he cannot describe.

The Kwaio, simply but proudly following the ways of their ancestors in a world that has passed them by, provide a rare chance to bring modern technology to bear on old anthropological problems. By sharing their world with an anthropologist and pouring out to him their vast store of experience, lore, and mental bookkeeping, they have opened important insights on tribal social life. But this joint venture of theirs and mine has not only helped to chart possible paths for anthropology. It has also illuminated what social scientists cannot do, cannot understand. and cannot write about—and hence illuminates the continuing mystery that is man.