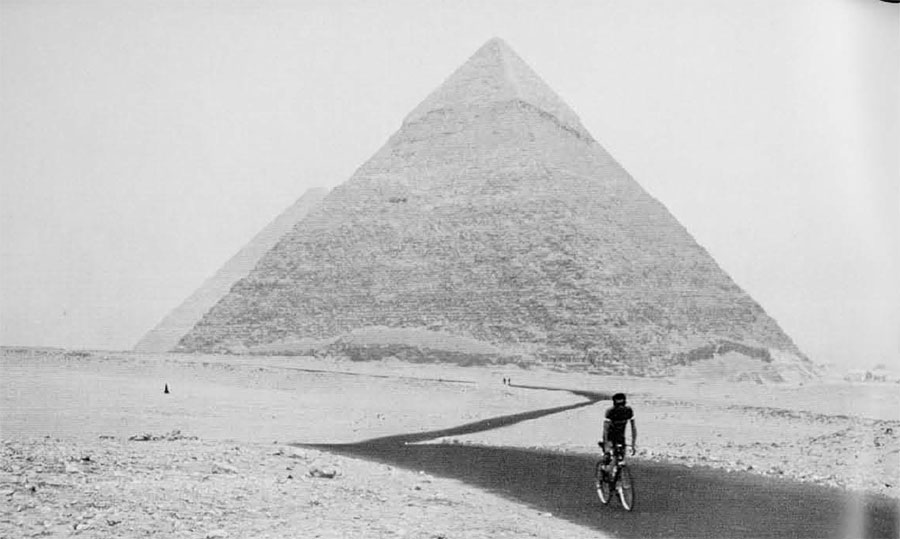

A recent issue of Courier published by UNESCO, makes the point that archaeological monuments and museums spark tomorrow’s tourist explosion in many parts of the world. Jets and the affluent society in Europe and America now make possible the massive movement of people right around the world to regions and countries which were little known to Westerners a generation ago. And in a great many of these regions, now being discovered by the jet tourist, the chief attraction is history, graphically represented by ancient monuments, sites, and museums of antiquities.

Tourism has become a very big business indeed (57 billion dollars in national and international tourism for the world as a whole in 1965). For many countries today, it is a major, even critical “export,” producing the essential foreign currency in a new kind of technical-industrial world. Many governments, well aware of the relation between history and tourism, are going all-out with capital investments in the development of archaeological sites, monuments, and museums. For example, the Mexican Government has invested millions in the excavation and restoration of Teotihuacan hear Mexico City and in a brilliant new museum of anthropology; Jordan, which receives about one quarter of its foreign currency earnings from visitors to its historic sites, now has an expensive seven year plan for developing these sites. The Iraqi Government also opened, in November 1966, a multi-million dollar museum of antiquities, which sets a new standard for its predecessors in Europe, and now encourages many foreign archaeological expeditions to work in Iraq, realizing that this also encourages tourism. There are scores of such examples of the relation between archaeology, tourism, and national policies to develop a booming industry.

What does all this mean to the professional study of archaeology? The current rise in archaeological tourism, and the predicted explosion, probably are both a cause and a result of a general increase in the popular study of the past in all countries—a development which may be due simply to the steady increase in the level of education or more probably to a current awareness of the significance of world history. With the present network of international communications, and the rapid diffusion of western ideas and technology, the educated began to see the history of human affairs as all of one piece. What happened in Thailand two thousand years ago, and what is now happening there are parts of an interrelated world pattern and a pattern which hopefully we can learn to understand. Such a view of history has been peculiar to the students of anthropology and archaeology for two or three generations. Now it becomes the accepted view of historians and the educated public as a whole.

In any case, whatever the causes, the results of the rising interest in the past on an international scale, which is reflected in archaeological tourism, do have a remarkable effect upon professional studies in archaeology. One way of illustrating this is to describe what has happened to the University Museum in the last decade.

Originating in the Victorian period as the result of a conversation between a banker and a divinity school professor, one afternoon at a camp in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, it has remained in many ways a nique institution. From our point of view today, the Victorians thought in terms of black and white with no intermediate shades. They were determined to collect all the facts and draw absolute conclusions in an orderly and systematic way. They had a self-assurance and certainty which today we may secretly admire but not emulate. At that time, our banker and professor decided to find the facts about the history of the Old Testament and so launched the first American excavation in Mesopotamia. They set the basic tradition of the Museum—to dig and find out.

But as the world view in archaeology and anthropology developed in Europe and America, excavations of ancient sites and the study of living primitive people by professionals on the Museum staff expanded into all continents, and far beyond the study of Western society alone. Nevertheless, work in the field the accumulation of original data, and the ordering of conclusions so that they are clear to layman and professional alike, have been guiding policies ever since that Victorian beginning. The customs of our generation which call for extreme specialization, and often a smoke screen of esoteric jargon to impress the layman, to a certain extent run counter to these policies. But we still believe that if you are going to study mankind, then men in general should understand what you conclude.

With this kind of tradition the University Museum naturally has been caught up in the current popular enthusiasm for knowledge about other people, other places, and past ages, and as a result has grown at a remarkable pace.

Ten years ago, the Museum sent out six exhibitions to seven countries; this past year, 1966, it has had 18 expeditions in 14 countries. In the same period its professional staff has increased from 11 to more than 30. This means that the supporting staff in the Museum and in the field has also increased from an estimated 110 to 225. During the same period, University graduate students in archaeology and anthropology, trained by the Museum staff, have increased from 32 to 144. General visitors to the Museum (which exhibits exclusively anthropological and archaeological materials, or ancient and primitive art) have doubled in the same ten year period.

But these are only the gross figures reflecting what appears to us a very sudden and rapidly increasing interest in the past. There are many other subtle and more complex results of this development. For example, a task force of senators and representatives set up by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, recommended that the University Museum spread its knowledge of the past throughout the State, and special State funds were appropriated for thuis purpose. The Museum now is inaugurating a State-wide educational program; today, members of the Museum staff appear on five television and radio programs, both educational and commercial channels, which reach out to many millions of people; the Museum itself is utilized for conferences and other special functions (187 in 1956, 424 in 1966) not only because it is a convenient building but because doctors, engineers, chemists, government representatives, and businessmen wish to return year after year to meetings where they can visit collections of objects out of the past.

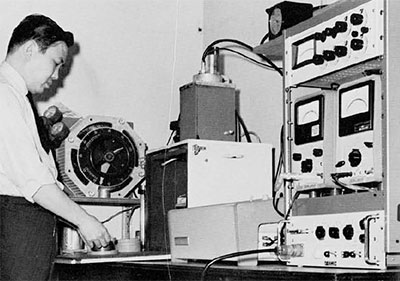

Another curious development of the past decade, reflecting broadly based interest in the past, is the growing collaboration between the Museum’s staff and researchers in other fields. Botanists, biologists, zoologists, ecologists, geologists, oceanographers, as well as physicists, chemists, and engineers, not only aid the archaeologist in reconstructing past events, but rely upon Museum personnel for data to solve some of their own problems. Hence, laboratories of various kinds are now added to the libraries as needed equipment for studies in the humanities. This collaboration between many research disciplines in studying the past, which indicates a basic change in the methods of archaeology and anthropology, probably would not have developed without a popular knowledge and interest in the subject.

Yet another phenomenon, which directly affects the University Museum and relates more specifically to archaeological tourists, is the current interest in the restoration of national monuments. Williamsburg, Independence Hall, and to some extent Society Hill, some of the most popular tourist centers in this country, are examples of the trend in America. Those who travel in Europe are equally familiar with the open-air museums in Scandinavia, innumerable restored and preserved historic buildings in all countries, and even entire museum cities like Bruges. But this enthusiasm for restoring and preserving national treasures is at present spreading to Latin America, Africa, and Asia, where the developing countries have just begun to recognize the economic and political advantages in restoring monuments which become at once an important source of foreign exchange and a means of consolidating national pride and national stability.

In Guatemala, the University Museum during the past ten years, spent almost one million dollars excavating and restring the Maya city of Tikal. Today, the Museum continues on the same scale with funds supplied by the Guatemalan Government. In Turkey, the Government has gone to considerable expense to preserve the tomb of Gordius, excavated by the Museum at Gordion; and also has established a museum at Bodrum to house antiquities excavated by our undersea expeditions off the coast, there. In Libya, the Government has proposed that the Museum staff direct continued excavation and restoration at Leptis Magna with all local costs supplied by Libya. In Egypt, University Museum expeditions worked in Nubia as part of the international effort to save the monuments before they were flooded by the high dam, and at present one of our groups is working at Luxor attempting to recover the historic records carved on the blocks from a destroyed temple of Pharaoh Akhenaten.

Although the University Museum’s primary concern is excavation and research, it is inevitably caught up in the current international concern about restoration and conservation of archaeological sites, and thus will be increasingly involved in the predicted burst in archaeological tourism around the world.

Largely because of popularization in archaeology and anthropology, the University Museum has rapidly become a major center for advanced University training in these subjects and the nerve center for a network of international operations which are primarily research expeditions, but which also include large-scale restoration and conservation projects, the establishment of local museums (in Turkey and Guatemala), experiments in new archaeological techniques, such as undersea excavations and aerial surveys with new remote sensors, and anthropological studies having to do with contemporary social and political problems.

With such an expansion during the past decade, the University Museum is now forced to add a four-million dollar wing to its present building, which we hope will be financed and completed by 1970. The Courier article is just one more warning of a current phenomenon that will inevitably increase the demands upon the teaching and research staff and upon the Museum itself. However, those scholars who proclaim the world view of history should be gratified that the masses of people are now discovering the rest of the world and its past as students, educated readers, or as tourists. We expect that the Museum will play a still greater role in the interaction of ideas among all these people.