An evaluation based on discussions with William Fagg, Deputy Keeper of Ethnography in the British Museum.

The art of Benin is the most widely known of all forms of “primitive” art, yet it is also the least typical. It is, moreover, the most highly valued, and indeed, as to a great part of its output, the most over-valued, perhaps because its special characteristics, which are the chief source of its interest for the study of art history, have not yet been fully understood. For, while a study of auction and other prices might suggest a certain evenness of quality, with prices often varying roughly in proportion to size, the story of Bini sculpture is, in fact, one of more or less continuous degeneration from the highest artistic standards in the fifteenth century to something approaching the lowest in the nineteenth.

Benin art, in the forms in which it has become famous in the past six decades, belongs to tribal art only in the sense that the Bini, among whom and by whom it was produced, are a tribe; but so far from being in any full sens the art of the tribe as a whole, it was virtually confined by law within the mud walls of the palace compound at Benin City.

The Bronze Founders, a closed guild occupying their own street hard by the palace under their own Chief Ine, were on pain of death permitted to work only for the Oba, and only he could, and in rare cases did, grant to a lesser chief, for some great service rendered, the right to own a bronze altarpiece or other major work of the guild.

The early history of Benin is not yet known with any certainty, but the internal evidence of the Benin and Ife antiquities accords well with the old Benin tradition that the early Oba Oguola–supposed to have reigned about A.D. 1280–applied to his spiritual overlord, the Oni of Ife, for the services of a bronze founder o teach his people to make the memorial bronzes formerly imported from Ife, that they might be made in Benin. The memory of that great craftsman, Igue-Igha, sent from Ife to teach that Bini is still venerated at his shrine at the house of Chief Ine in the Street of Brass Casters.

The Ife aesthetic, a refined and idealized naturalism, seems to have been for a time successfully transplanted to Benin. The earliest Benin works known to us, the thinly cast, nearly life-sized heads, which date from about A.D. 2500, are almost as realistic as those of Ife, although some features have been markedly stylized. Moreover, perhaps under Ife stimulus, the Bini artists at this time had a special contribution of their own to make, which places certain works of the early period, such as three fine heads in our own collections (one is shown on the cover), on a level of original artistic achievement probably equal to that of the best Ife works themselves.

Throughout what we know as the early period, probably coterminous with the sixteenth century, the subtle Ife model remains dominant in the Benin bronzes, although a strong impression remains that it was merely copied rather than fully understood by Igue-Igha’s Bini pupils. It is still very evident in the fine Queen Mother head in our Museum (1), which may be considered transitional between the early and middle periods. But by the middle period itself, subtlety and individuality have been sacrificed to the setting up of the conformist canon which we know so well from the great series of wall plaques (2), from the imposing round sculptures in the same style (3), and from the simpler of the thick-necked heads. In these, a remarkable stylistic equilibrium has been achieved, and even if high competence is more conspicuous in them than originality, they have their parallels in equally stolid though highly esteemed arts such as those of Assyria, Egypt, and Imperial Rome. Occasionally a talented artist might produce notable works in spite of his time, just as decadent Greece produced the Melian Aphrodite and the Nike of Samothrace. Mr. Sturgis Ingersoll’s well-known Hornblower and the beautiful pendant mask, collected by the late Admiral Sir George Egerton on the Benin Expedition in 1897 and now in the Plass Collection, both of which have been exhibited at the University Museum, are magnificent sculptures of the middle period.

Because the Benin court style was by origin an alien importation without roots in an indigenous tribal art, the prolific middle period does not seem to have lasted more than about a century and a half–roughly from 1600 to 175o–before giving way to a long decadence, which became more and more flamboyant and empty of feeling (4), as the Benin empire waned and the debacle of 1897 approached.

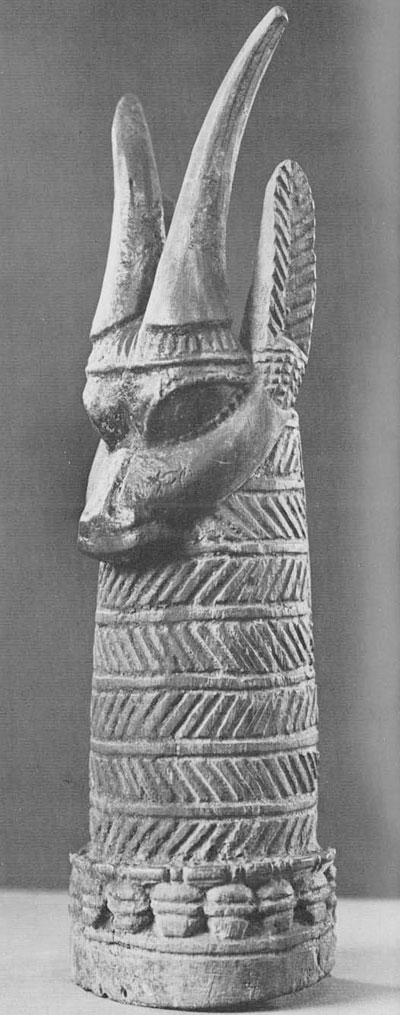

The long process of Benin art history then is one of “primitivization,” a relapse from the high culture of Ife, which is all the more interesting because, without the sustaining religious faith which informs the true tribal sculpture of Africa, it remained artistically negative, entirely lacking in the imaginative dynamism found in the true tribal style of Benin, still almost completely unknown. This tribal style is found mostly in villages at some distance from the capital city, and consists of large figures modelled in the clay of the village earth and of wooden sculptures made for the altars of the local chiefs and for the domestic altars of the villagers. Only a month ago, a finely stylized head of an antelope, similar to the one in our Museum (5), was found in Usen, a Bini village forty miles to the northwest of Benin, and another, at Ugboko, far to the southeast of the capital. According to our records, our head was found at Benin, and this is quite likely, as in the days of its greatest power, the empire of the Oba of Benin was the dominant power of the Guinea Coast, with its influence extending over peoples of many languages and cultures, most of whom paid tribute to the Oba and sent gifts for his royal altars.

Photographs by: Reuben Goldberg