The impetus to record a previously unwritten language must be powerful, since it requires adaptation to a new kind of communicative device and thus must reflect and cause alterations in the group that becomes literate. Here I examine the process through which one illiterate society went when it confronted literate ones and the reasons why writing was adopted. The Phrygians, when they settled in central Anatolia in the early first millennium B.C., felt the need to record their language. The script of the Phrygians seems to have been modeled on Creek, so the driving force to write their language may be discerned by investigating similarities of usage between the two.

Phrygian writing is well represented at the site of Gordion, where The University Museum has conducted archaeological research since 1950. The site is located approximately 60 miles southwest of Ankara in modern Turkey (Figs. 1, 2), the ancient Anatolia, on a major east-west transportation route which became part of the Persian Royal Road. Since Gordion was inhabited for nearly three thousand years, it received linguistic influences from many groups—Early Bronze Age settlers (whose language is not known), Hittites. Phrygians, Persians, Creeks, Romans, and Galatians. The Phrygian script, however, derives directly from the Creek.

Bronze Age Writing at Gordion

The earliest writing at Gordion dates to the Late Bronze Age, 14001200 B.C. This phase of the settlement was contemporary with the Hittite Empire, and shared aspects of material culture suggest that Cordion was within the Hittite political and economic sphere. Several Bronze Age seals and seal impressions have been found at Cordion, including a jar handle with the impression of a seal containing Anatolian hieroglyphic characters, as yet undeciphered (Göter-bock, in DeVries 1980:51). This type of writing is usually called Hittite Hieroglyphic, although it actually represents a Luwian sister language of Hittite that was widely spoken in western and southern Anatolia (Hawkins 1986:368).

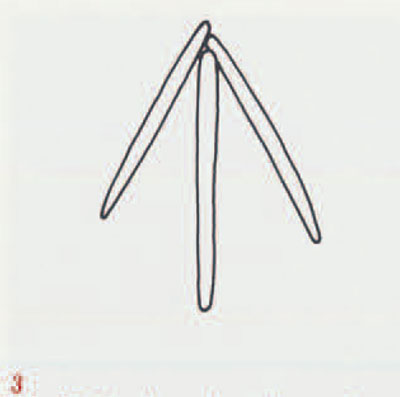

Also found in Bronze Age Gordion were pots bearing signs that had been incised before the vessels were fired. Two different signs occur, the arrow (Fig. 3) and the triangle with central line (Fig. 4), both of them several times. Probably identification marks of some sort, these signs are not a form of actual writing, although one, the triangle with central vertical line, may be a simplified form of the Hittite hieroglyph for king. Such signs on pots are distributed widely throughout the Hittite Empire, for example, at Alaca Huyuk and Tarsus, as well as at the Hittite capital of Hattusha, the modern Bogazkay (Fig. 5).

The evidence for writing at Gordion during the Late Bronze Age is slight. The graphic symbols used were probably simple recording or identifying devices, and Hittite cuneiform texts on tablets comparable to those found in the Hittite capital and some major Hittite cities are absent. Based on present evidence, therefore, Cordion was not literate in the way that, for example, Hattusha was. Nevertheless, hieroglyphic writing was present at Cordion and may be related to scripts used in the Hittite Empire.

Development of Phrygian Script

The centuries immediately following the collapse of the Hittite Empire in Anatolia (ca. 1200 B.C.) are called the Dark Ages, because we lack both written records and archaeological definition for the period. The Phrygians entered central Anatolia and settled at Cordion during this time, having come from Thrace and Macedonia according to the Creek historian Herodotos (7.73). They are recognized as a distinct people in part through their now-extinct language, which has been assigned to a linguistic group called Thraco-Phrygian, possibly related to the Hellenic branch of the Indo-European language family. Phrygian was only distantly related to languages of the same family that were spoken in Bronze Age Anatolia. It is not fully understood, largely because few long texts are available, so we do not know the extent to which it was affected by the languages with which it came in contact in central Anatolia.

Our knowledge of Phrygian script derives from two sources—early texts in Phrygian alphabet and neo-Phrygian inscriptions written in Creek characters. The early Phrygian alphabetic script has close affinities to the Greek alphabet. Since the earliest Phrygian writing does not occur until the 8th century B.C., considerably after the settlement of the Phrygian people in Anatolia, we must ask why these people adopted writing when they did, and why and how they chose an alphabetic script probably based on the Creek system.

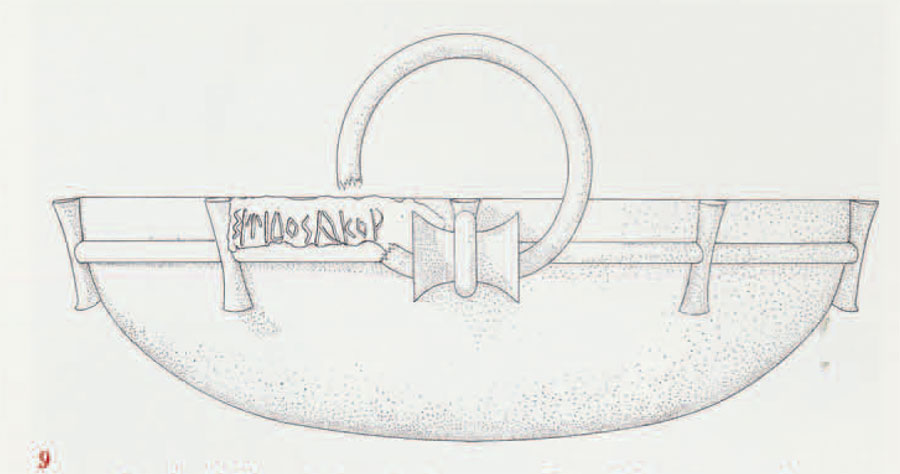

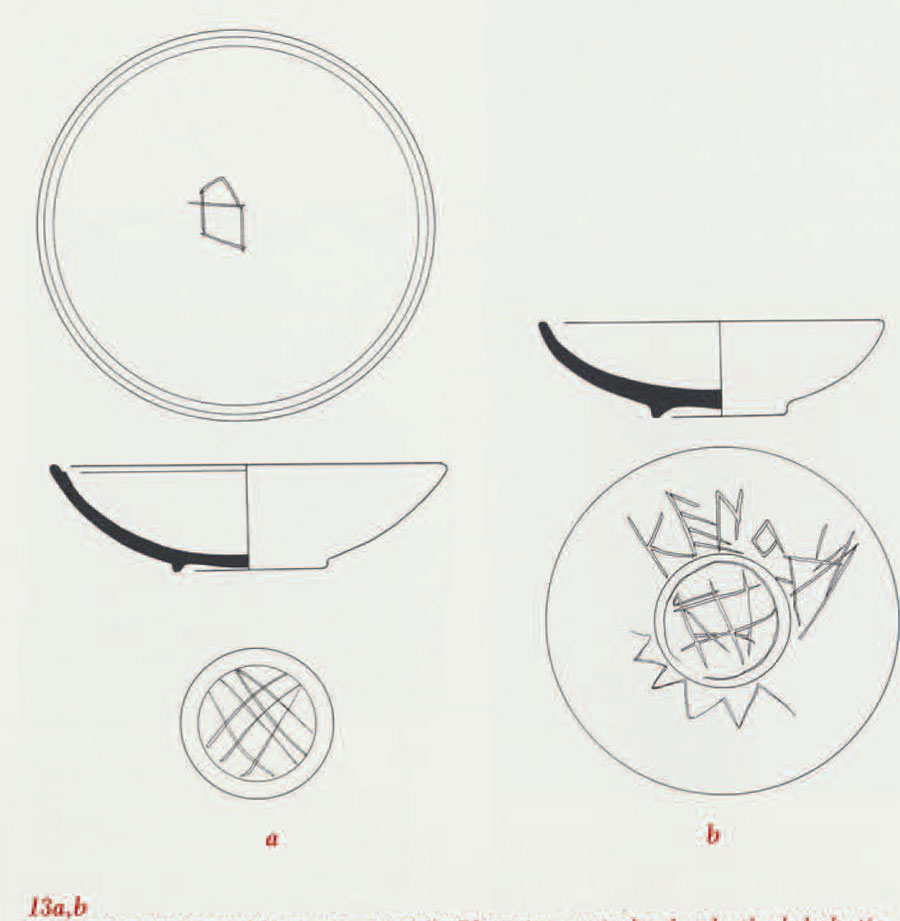

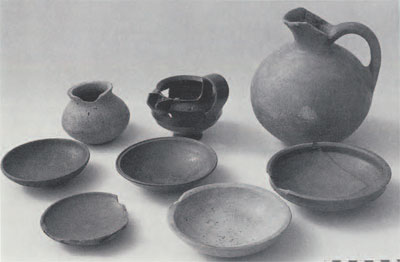

The development of the Greek alphabetic system has been a much debated subject. It seems likely that the Greeks were exposed to writing through contacts with the Phoenicians in the northern Levant, and modified the consonantal script of the Phoenicians to create vowels and other characters which the Greek language required. The transmission, which probably took place no later than the first half of the 8th century B.C., could have been accomplished by Creek merchants living in the Levant who perceived the need for a recording system in order to keep up with their trading partners (Jeffery 1961:1-40). Among the earliest Creek writings are graffiti on pottery—words scratched onto a bowl or jar, usually proper names as forms of identification. But complex texts in Creek are equally betic script. The piece bears a mark incised after firing, a triangle with a central vertical line (Fig. 6). This, as we have noted, is the same mark that appears on several Late Bronze Age sherds at Cordion (e.g., Fig. 4), and is probably a form of the hieroglyph meaning king. Since the Iron Age mark was on a small vessel, it is unlikely to have had any real connection with royalty, but it must have had some meaning in the Phrygian context. A clearer demonstration of the Phrygians’ knowledge of the past occurs on another Late Bronze Age vessel, found in a mixed deposit of 5th and 4th century B.C. material (Fig. 7). This too has the Bronze Age sign, the triangle with the central vertical line, and beneath it is a graffito in Phrygian alphabetic script. The Hittite capital at Boazkoy was devastated around 1200 B.C. and may not have been reoccupied for some time, but Cordion may not have been so totally destroyed. The new Phrygian immigrants might have seen Hittite objects at Gordion, and some parts of the Bronze Age population in that area could have survived. Exposure through random chance (as illustrated by Fig. 7) to the Bronze Age practice of.

From Phrygian to Greek

A second stage of Greek influence on Phrygian writing occurred in the 4th century B.C., four hundred years after the introduction of the alphabet, when Creek letters and Creek orthography appear in graffiti on pottery. At this time, since there was still considerable overlap between the two writing systems, the actual evidence for the shift of script is subtle; the distinctive Phrygian letter forms ^ and 4/ disappear, and several Greek letters not seen before this time, e.g., H, A , 4 , are found. Other Creek practices, such as the use of ligatures, occur for the first time. Eventually Greek script supplanted Phrygian, and Greek spelling was used in writing common Phrygian proper names. Also from the 4th century are the earliest examples of texts with words and phrases in the Creek language, suggesting that the changes in the writing system resulted from the introduction of Greek speech as well as Greek script. By the end of the 4th century, texts in the Phrygian language had become rare, with most being written in Creek. By the 3rd century B.C. all the written documents at Cordian are in Creek language and Creek script (Roller 1987b:107). This linguistic shift is attributable to profound changes in the political organization of Anatolia after the conquests of Alexander and his legendary feat of cutting the “Cordian knot,“ by which he gained possession of Asia. The successor states formed from Alexander’s empire after his death were strongly Hellenized, so Greek passed from being a lingua franca to the mother tongue of many conquered peoples, the inhabitants of Gordion among them.

Conclusions

The Phrygian writing system drew upon two separate script systems—Anatolian hieroglyphs and the Creek alphabet. Each derived from outside Phrygia, but the reasons for their adoption seem to have varied. During the Late Bronze Age at Cordian, the writing system and the use of non-verbal graphic symbols appear to have been limited to recording ownership. Even this function was lost at the end of the Bronze Age, due to population movements which included that of the Phrygians. The desire to write the Phrygian language came several centuries later, as a result of exposure to Creek writing. The Phrygian alphabet seems to have been known to a larger percentage of the population than was Bronze Age writing, although the subject matter of extant Phrygian texts is limited in scope. An indigenous element persisted, as non-verbal symbols were frequently used in conjunction with alphabetic writing. The final shift in the writing system, from the Phrygian to the Creek alphabet, occurred when political changes in Anatolia in the 4th and 3rd centuries B.C. caused Greek to become the dominant language.