Many of the myths that plague archaeologists come from outside the profession, the product of overly imaginative minds untrained in the scientific study of the past and unfamiliar with the archaeological evidence. There are, however, a few very popular and widely believed myths about the past that come out of the discipline of archaeology itself and that are based on evidence collected and interpreted by professionals.

It is a part of the process of science that ideas arise, are later recognized as mistaken, and are dropped. However, when an idea is so spectacular or so romantic that it escapes from the dry pages of scientific journals and catches the public imagination; when it becomes firmly entrenched there; and when it continues to color people’s ideas about the past long after it has been proven groundless—then it begins to take on the aspect of other legends like those of Atlantis or of the peopling of the Americas by the Lost Tribes of Israel.

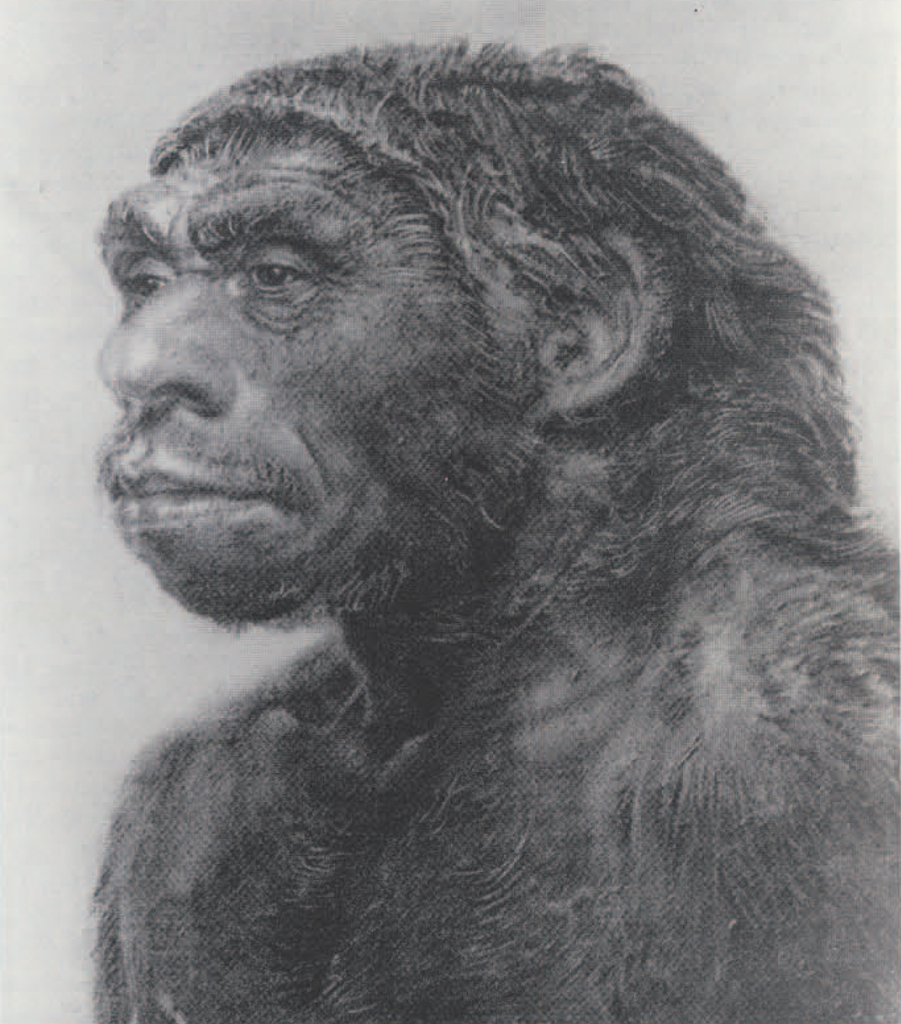

The Cult of the Cave Bear is such a myth. The idea that Neanderthals (Fig. 1), the predecessors of modern humans in Europe, were engaging regularly in religious rituals involving the sacrifice or the worship of the now extinct cave bear appears to have been suggested separately by at least two excavators of cave bear dens early in the I920s. By 1975, a detailed analysis debunking all the evidence for such a cult had appeared in print. Yet since that time, best-selling novels, major Hollywood movies, and even college textbooks have portrayed the Cult of the Cave Bear as not only to have been found. Why the evidence is no longer to be taken as proving the existence of such a cult can be understood by examining the same evidence in the light of new methods and knowledge. Why the notion continues to be popular is harder to understand.

The Dragon’s Cave

In the years between 1917 and 1921, in a deep cave high above the Tamina Valley in Switzerland, Dr. Emil Bächler uncovered a series of spectacular finds. The sediments that filled the cave of Drachenloch (“Dragon’s Cave”) had been laid down during the Ice Ages, when both cave bears and Neanderthals flourished in Europe. What he found led Bächler to conclude that relationships between the two species had been more than casual.

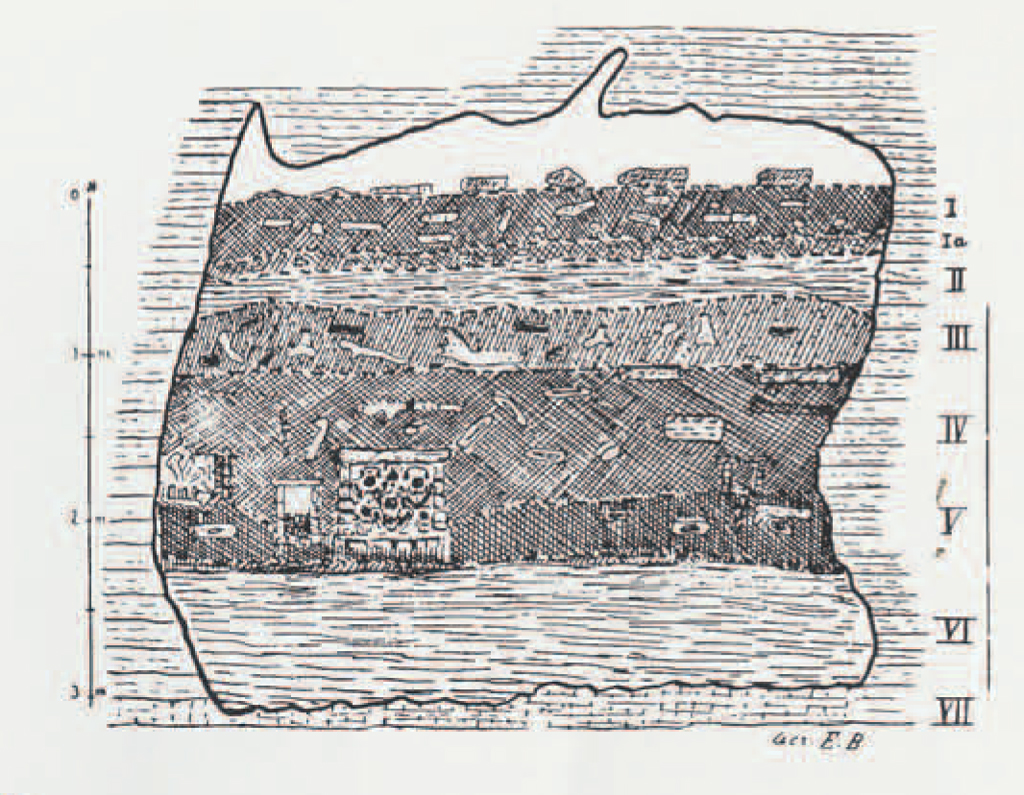

The dirt and rock debris that filled the cave was full of bear bones. This in itself was not surprising, since cave bears used caves for hibernation (hence the scientific name Ursus spelaeus or “cave bear”) and, over centuries of such occupation, died in large enough numbers to leave abundant bones to be found by future excavators. But some of the deposits of bear bones found by Bächler’s workmen appeared to be far from natural. In two of the interior chambers were low mortarless stone walls, up to about 10 inches high, located 15 to 25 inches from the bedrock walls of the cave. Such constructions were in themselves remarkable, for elsewhere the only stone structures attributable to Neanderthals are extremely crude, consisting of irregular circles of rocks that were probably used to weight the bases of tents or windbreaks. In Drachenloch, however, not only were there walls, but behind these walls were found accumulations of bear bones — the long bones of the legs and more or less complete skulls. The pattern was very consistent. Where such walls were present, bones were present. Where they were absent, bones were rare along the cave walls.

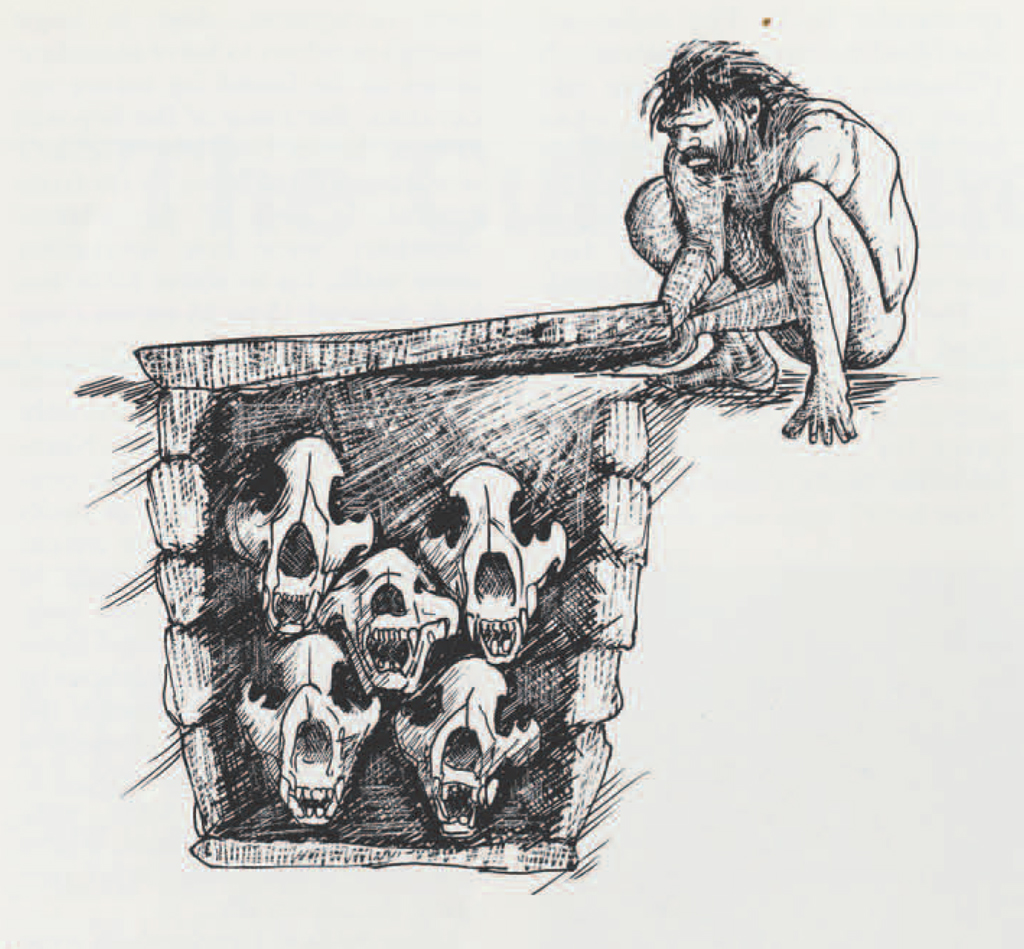

Other finds at Drachenloch were even more spectacular. Bächler found “about six” carefully made dry masonry chests, or cists, full of bear bones. One of these in particular has become famous. It was about three feet high and covered with a large limestone slab. Inside it were a group of cave bear skulls, all carefully aligned in the same direction. While workmen destroyed the chest before it could be photographed, Bächler published a sketch of it, drawn in cross-section some time after the excavation (Fig. 3). Many of the bones in these satisfyingly romantic but true as well.

How the myth came into being can easily be understood if we look at the most famous of the sites where ritual remains were thought cists exhibited the toothmarks of large carnivores, indicating that they had little or no meat on them at the time they were deposited. For this reason, it is unlikely that they represented caches of meat made by Neanderthal hunters. At the same time, the construction of the cists and their protection by stone slabs made it seem unlikely that the bones were deposited naturally.

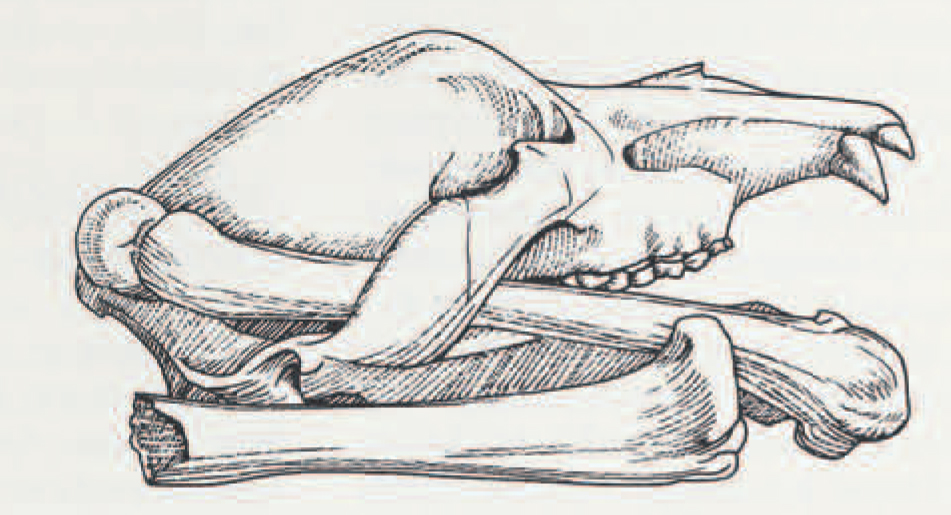

Bächler also found a bear skull in another part of the cave, lying upright between two shinbones, with the thighbone of a bear thrust through the gap between the cheekbone and the skull (Fig. 4). Because the thighbone had to be twisted ninety degrees to get it through the opening, it seemed unlikely that it got there by accident. Elsewhere were other skulls, in niches between rocks, covered by slabs, sometimes vertical, sometimes horizontal, all of them apparently put in place by Neanderthals.

Because these cave bear deposits seemed to have no practical function, and because of their rather spectacular nature, they were taken by Bächler to be ritual deposits. The idea of cave bears as the objects of ancient Neanderthal rituals immediately became a part of the scientific view of Neanerthals (Fig. 5). And the notion of the Cult of the Cave Bear found support at other sites, where similar, although usually less spectacular, finds were excavated both in the same decade and in the decades since.

Archaeological Problems

The idea of a cave bear cult had its detractors, however, from the beginning. One such was the French prehistorian Dr. F. E. Koby, whose objections were quite clearly voiced. In fact, one reason his arguments were not more widely accepted may well have been that they were so strongly stated. Of a scientific group that had reported evidence of cavebear worship at a site in Austria, Koby wrote:

One may hope that they will acquire some experience and an ounce of common sense. The article in Natur and Technik is of some interest from the psychological point of view, allowing one to infer a certain collective suggestibility and constituting an interesting contribution [to our knowledge) concerning the formation of legends. (1951:9)

While such eminent prehistorians as the Frenchman Andre Leroi-Gourhan argued against the existence of the cave bear cult, it was not until a young paleontologist and archaeologist named Jean-Pierre Jéquier made a detailed case-by-case study of all the reported evidence that it became clear that in no case was the evidence sufficient to prove the existence of such a cult. Basically, Jéquier pointed out that there were two problems with the arguments and evidence presented in favor of the cult. The first had to do with the way in which the data were collected and reported. The second had to do with what people had learned since Bächler’s time about the way in which caves are filled, and the effects that these processes have on materials in the caves. A look at Drachenloch and one or two other cases will show how what Koby called legends” can arise from within the field of scientific research.

Archaeological Methods and Reporting

At the time Bächler was excavating, archaeology and paleontology were far different disciplines than they are today. While excavators were aware of the general principle that finds are of use to science only to the extent that their context is known, context was generally studied and reported on a much grosser scale than it is today. Today digging is done by trained excavators or students, and detailed, carefully measured drawings and photographs of even run-of-the-mill matters—not to mention spectacular finds such as those reported by Bächler —are part of the routine documentation of any excavation (see box).

Drachenloch, however, was excavated by workmen. Although the excavations were conducted under his overall direction, Bächler was not at the site continuously; he simply visited it at various times during the work. In fact, he was absent when the skull with the thighbone through the cheekbone was found. While Bächler kept track of the gross changes in the layering of the cave fill and of the general shape of the cavity of the cave, he did not make measured drawings of the dry masonry walls, cists, or bone deposits — or, for that matter, of anything.

Had Bächler followed modern practices, we would today have careful records of exactly what each find looked like. There would have been photographs and measured drawings showing the exact shape and position of each stone in the walls and cists, and of the exact position of each bone in the deposits. The reader of the report would be able to see for himself what these looked like. In fact, however, all we have are Bächler’s descriptions based on his interpretations of the finds. We must accept that the cists were carefully constructed because Bächler says they were. We must accept that the low walls were made by humans because they looked that way to Bächler. We must, that is, accept Bächler’s judgment, since he has left us no way to judge for ourselves. As Jéquier expressed it (speaking not only of Bächler but of most of the evidence for cave bear rituals):

The facts are not recorded in the “raw state”, but already partially interpreted, already masked by a varnish that it is impossible to remove after the fact. The terms used are very significant: one author writes of a “dry-stone wall” instead of a pile of stones; another, of plaques forming a pedestal instead of a flat stone on which the skull was resting. The nuance is real, which is not to say that it is not justified here or there; to convince us, a more detailed explanation would nevertheless be more effective than the simple affirmations that we are given. (1975:47-48)

Is there, however, any evidence that Bächler’s descriptions are not accurate? While no one would suggest that Bächler was in any way intentionally distorting the evidence, there is indeed reason to think that his interpretations clouded his descriptions.

Some of this evidence can be taken from Bächler’s own reports. The sketch he made of the cist full of cave bear skulls in 1923 (Fig. 3) differs drastically from one he published in 1940 (Fig. 6). The cross-section of the limestone cavity and the order and numbering of the layers of fill are similar, but the cist and its contents are not. In the earlier drawing, the orientation of the skulls is different, as is the number of skulls shown. The size of the cist with long bones immediately adjacent to it differs greatly in the two drawings. Perhaps even more damning is the fact that the method of construction differs in the two drawings, from horizontal slabs in 1923 to vertical ones in 1940. Moreover, by 1940 a wall has appeared to the south (left) of the cists, containing more bones. As Koby pointed out, the later drawing not only differs from the earlier, but the ways in which it differs indicate that Bächler’s memory was being affected by his interpretation. The cists were better built, there were more of them, there were more skulls and bones in the structures. Koby perhaps carried his argument too far—he suggested that the new orientation of the skulls to the east rather than the south may have been because Bächler felt this was a more orthodox direction. Nevertheless, it is clear that Bächler was relying upon his memory, and that, at least to some extent, his memory was being affected by his interpretations of what he saw.

That this may have been the case in his 1923 report can be seen from the field notes kept by T. Nigg, the man who actually conducted the excavations. By contrast to Bächler, Nigg, whose notes have never been published, was at the site continuously. While Nigg shared Bächler’s ideas about the cave bear deposits, his notes (read in detail and cited by Jéquier) provide a rather different perspective upon the finds. Where Bächler spoke of walls, Nigg’s notes mention only two places where stones were piled vertically. Neither of them, according to Jéquier, was associated with any particular collections of bones. Moreover, while Bächler had emphasized that even the workmen were able to recognize the walls as human handiwork, Nigg made it quite clear that he could not decide whether they were intentional structures or merely accidental accumulations of rocks that had fallen from the cave roof.

Nor did Nigg ever write of stone chests. Rather, he spoke of cavities or holes filled with bones (“Knochengruben”) covered by large limestone slabs. In this regard, Jéquier points out a rather interesting feature of Mohler’s description. While he describes the cists as carefully constructed rectangular structures, he reported “about six” of these chests. If the structures were as carefully made as Bächler describes, they should have been readily identifiable. In this case, since they were of such importance, Bächler should have known how many there were. The inescapable conclusion is that they were not as easy to recognize, and therefore not as carefully constructed, as his descriptions would suggest.

Nevertheless, there do appear to have been cavities filled with bones and often covered with large flat rocks, and there is no reason to disbelieve the report of a bear skull with a thighbone thrust through the cheekbone. Even if Bächler’s interpretations of what he saw led him to exaggerate the quality of Neanderthal workmanship, the fact remains that he, at least, was convinced by what he saw. But if there were patterned deposits of cave bear bones found in the cave, and they were not the result of deliberate human activities, how can they be explained?

The Nature of Cave Deposits

Uchler’s interpretations of the animal bones from Drachenloch were entirely reasonable given what was known about the mechanics of cave filling at the time. In fact, other scholars have reached the same conclusions based on similar observations at other sites. The fact is, however, that we now know enough about how material is deposited in caves so that we can find natural explanations for what Bächler and Nigg saw.

Caves like Drachenloch are formed when the limestone bedrock is dissolved by water. Once the cave is open, however, other factors come into play, so that caves are often filled with materials ranging from large blocks of rock to very fine silts and clays. In caves dating to the Ice Ages, much of this fill consists of rocks, varying in size from ones an inch or two across to ones weighing tons, that were pried from the cave walls and roof by frost action. Many of these are rather flat in cross-section. Moreover, once large blocks had fallen they were often further attacked by frost action. Nigg described one mass of flat rocks piled one upon another that he interpreted as a wall. Further work, however, led him to realize that this was simply a large block that had been split into leaf-like layers by natural weathering, and that the leaf-like fragments had remained approximately in place, giving the impression of a very carefully constructed dry masonry wall.

When cave bears entered a cave to hibernate, they began by scratching nests into the cave fill. In the process, bones and small rocks were pushed aside, often falling into crevices among the fallen blocks. This had two effects. First, it helped to build up accumulations of bones in natural cavities among rocks or among piles of rocks. Second, it protected the bones that did enter such interstices from further trampling and, if they were buried there, from weathering and decay. It is perfectly natural, therefore, that modern excavators should find concentrations of bones in cavities surrounded by rock. Moreover, because further weathering of the cave roof naturally produced subsequent roof fall, it is perfectly normal that such cavities would be covered by slabs of greater or lesser size.

Because accumulations of rock are not necessarily random, the patterns of rocks and bones can often be striking. Leroi-Gourhan has described how he was fooled into reporting a circle of cave bear skulls at the site of Les Furtins in France:

It was a small chamber with sloping walls, approximately circular and about three meters [ten feet] in diameter. The bears… had dug out their lair, forming, with the complicity of the sloping walls, the most beautiful trap for prehistorians one could imagine. When the overlying material had been removed, the little chamber was surrounded by a circle of bear skulls, oriented in all directions, but for the most part horizontal and lying in place…. The work of the bears and the unconscious elimination of all the little bones had sufficed to produce a structure such that one could hardly doubt the intervention of man. (1964:34)

The walls and cists of Drachenloch, if they were indeed as Bächler described them, could not be explained by such natural processes. But we have seen that Bächler ‘s descriptions reflect interpretation, not the “raw” facts. As described by Nigg, they can indeed be explained by natural causes.

Even the thighbone thrust through the cheekbone has its parallels in nature. Koby described similar cases where, in deposits of bones dating to long before man’s entry into Europe, bones had been interlaced in highly improbable ways. One must remember that many cave bear sites such as Drachenloch are filled by thousands of bones. With such large numbers of bones being moved about by hundreds of bears, and given the laws of probability, it is almost inevitable that improbable juxtapositions will occur on occasion. Thus, it is not surprising that one should find, as a paleontologist did at the site of Salzofenhöhle, a cave bear skull with a pebble in the nostril, lying near two bones that happened to be parallel. This find was again taken to be proof of human ritual (Ehrenberg 1953). It is clear from published photographs that pebbles and bone fragments were plentiful in the area surrounding the skull. Yet the excavator ignored this larger context, and interpreted those pebbles actually in contact with the skull as evidence of ritual activities.

Jéquier evaluated not only the material from Drachenloch but virtually all the reported evidence for the cave bear cult. In every case, he made it clear either that the descriptions (like those of Bächler) reported what the excavator believed rather than what he had seen, or else that the phenomena observed had perfectly matter-of-fact natural explanations. In spite of this, the Cult of the Cave Bear remains firmly entrenched, not only in the public’s mind and in popular literature, but in textbooks as well. Why this is so is in itself an interesting phenomenon. One can understand the attitude of those who found Koby’s objections suspect on the grounds that they were overly strenuous, but neither Jéquier nor Leroi-Gourhan wrote in a manner that would imply bias. Jéquier’s study appeared in a publication that is not widely read by Ice Age prehistorians, but the same is not true of Leroi-Gourhan’s discussion.

The idea of a cave bear cult may have flourished in part because it is consonant with other ideas about Neanderthals held by many Ice Age experts. Archaeologists have found other, well-documented phenomena (such as intentional burials of Neanderthals and certain decorative or unusual objects) that have been interpreted as evidence of symbolism and religion. Moreover, many physical anthropologists are convinced that the biological differences between Neanderthals and modern humans are no greater than the differences among modern human populations. They have therefore concluded that Neanderthal lifeways were essentially modem, and probably included spiritual beliefs and ritual behavior. While there are many scholars who disagree with these conclusions, archaeologists not specializing in Ice Age Europe (including writers of textbooks) have had little reason to be surprised or skeptical about the cave bear cult. It is perhaps the specialists in Neanderthal archaeology who are most responsible for the fact that so few people realize how thin the evidence for such a cult really is.

Disciplines like archaeology are of little use if they do not provide society as a whole with information about past times, information in which the public has some interest. The idea of the cave bear rituals was based on observations by trained scientists working according to the methods current at the time, and interpreting the data in terms of the knowledge available to them. Subsequent research has shown that their conclusions were not as soundly based as they thought, but that is the way of science. Although the cult of the cave bear has caught the imagination of both archaeologists and the general public, it seems likely that just as the process of science has undercut its scholarly foundations, so the spread of scientific information will eventually remove it from textbooks and best sellers alike.

1960

Prehistoric Man. London: Paul Hamlyn.

Bächler, Emil

1923

Das Drachenloch ob Vättis im Taminatale 2445m ü. M. St. Gallen: Zollikofer und Cie.

1940

Das alpine Paläolithikum der Schweiz. Basel.

Ehrenberg, Kurt

1953

“Die paläontologische, prähistorische und paläo-ethnologische Bedeutung der Salzofenhöhle im Lichte der letzten Forschungen.” Quartär (1):19-51.

Jéquier, Jean-Pierre

1975

Le Moustérien Alpin: Révision Critique. Eburodunum II. Yverdon: Institut d’Archéologie Yverdonnois.

Koby, F. E.

1951

“Grottes autrichiennes avec culte de l’ours?” Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française 48: 8-9.

Kurtén, Bjorn

1976

The Cave Bear Story: Life and Death of a Vanished Animal. New York: Columbia University Press.

Leroi-Gourhan, André

1964

Les Religions de la Préhistaire (Paléolithique). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.