Old and probably ugly, with a nut-cracker profile. That is how Joseph McFarland, M.D., referred to the Soap Lady, one of the Mütter Museum’s most famous and enduring specimens. McFarland, the Curator of the museum from 1937 to 1945, also called her “one of the most revolting objects that can be imagined.” And, while it is true that the Soap Lady is not wholly photogenic, there is much more to her than meets the eye. She is one of the oldest and longest displayed specimens at the Mütter Museum of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, having been on exhibit for most of the 140 years since her arrival at the museum in a hired horse and cart. While we know much about how her body came to be the way it is, we know practically nothing about the woman herself. And to further complicate matters, scientific inquiry has proven false what we thought we knew about her.

Saponification to Mummification

Housed at the Mütter Museum in a wooden and glass case that bears a slight resemblance to the Snow White coffin in the Grimms’ tale, she is lying on her back, mouth agape in a toothless gasp, or scream, depending on your interpretation. Her hands are lightly resting on her legs, her toes slightly pointed. Her body has been blackened from years of Philadelphia pollution and the remnants of her hair form little wisps around her head. Her eyes appear to be both open and closed but are in fact shriveled up and sunken in.

While she is called the Soap Lady, she is not actually made of soap; she is a saponified body. Saponification is an event that occurs after death in which a body undergoes chemical changes that transform body fat into a substance called adipocere. Adipocere is a byproduct of decomposition. It is an organic material, with the consistency of semi-hard cheese and a soapy, waxy texture. It has also been called grave wax or corpse wax. In order for adipocere to form, the body must be in an anaerobic (oxygen deprived) and basic pH environment. Until recently it was thought that a waterlogged, or at least moist, environment was needed, but subsequent research has indicated that the moisture from the body itself can suffice. Specific bacteria are also a necessary ingredient, especially the type found in the intestinal tract of most humans. When a body is exposed to these particular environmental conditions, a chemical reaction occurs in which the fat undergoes a type of hydrolysis, forming fatty acid salts and other materials that make up the adipocere. During the adipocere formation, the water from the soft tissue is extracted, eventually making the body inhospitable to further bacterial decomposition. The adipocere is also not palatable to the types of insects that usually consume decomposing tissue so these bodies are left relatively intact.

People often ask whether the Soap Lady is a mummy. Some argue that saponification is not mummification; it is its own chemical process that alters the body on a molecular level. However, the end product of saponification is a naturally preserved corpse that needs no extraordinary environmental controls and has very low water content, similar to a naturally mummified person. Mummy or not, the Soap Lady is an enigma, and for that we can thank Dr. Joseph Leidy.

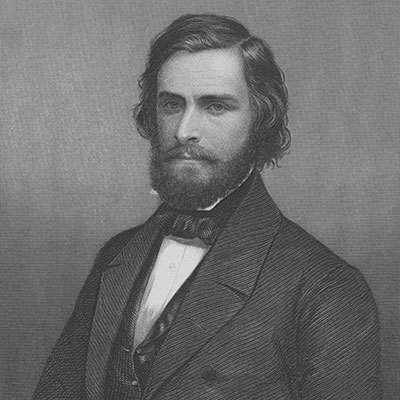

An 1874 Delivery to the Mütter

Dr. Leidy was a 19th-century Renaissance man: a physician, paleontologist, naturalist, and professor. A Fellow of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, he made numerous donations of specimens to the Mütter Museum. In 1874, he delivered to the museum one of two saponified bodies unearthed from a Philadelphia graveyard. The Mütter received the female, the Wistar and Horner Museum (now The Wistar Institute) at the University of Pennsylvania received the male specimen. The original labels for both specimens indicate that Leidy told the museums that the bodies had the surname “Ellenbogen” and that they both died of yellow fever in 1792. Additionally, the Mütter label indicated that the female was buried near Fourth and Race Streets. The staff at the museum accepted this information on the Soap Lady for over 65 years until Joseph McFarland investigated further.

McFarland methodically tracked down information about the Ellenbogens’ life and death in Philadelphia. He first had to contend with the name. While the Soap Lady was simply listed as “The woman named Ellenbogen,” the label of the Soap Man at the Wistar read “Body of Wilhelm von Ellenbogen.” The word “von” when added to a name in German signifies the individual is of noble decent. McFarland decided to look for any mention of either name in death records, church listings, ship logs, and any other records he could find. Not only did McFarland find no Ellenbogens, von or otherwise, in the death records of Philadelphia in 1792, he found no recorded deaths from yellow fever at all. He checked the published lists for the thousands of yellow fever deaths in 1793 and still, no Ellenbogens. In fact, he could find no one with that name in Philadelphia until after 1856.

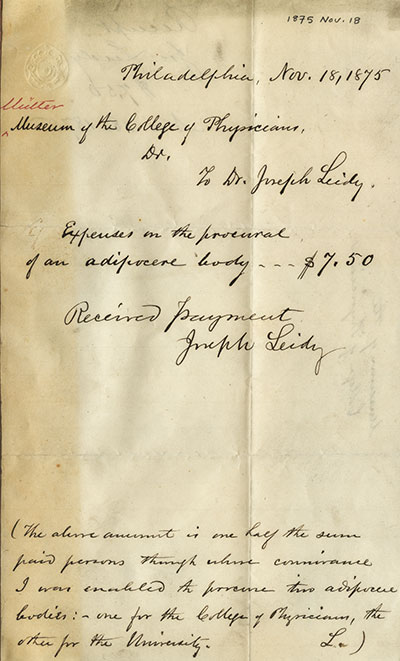

McFarland also researched the alleged location of the cemetery, near Fourth and Race Streets. He determined that while there were three German churches in that area, all of their cemeteries were elsewhere. The curious curator also scoured the archives of the library at The College of Physicians and there he found some interesting evidence that betrayed Leidy’s little lie. A handwritten receipt dated November 18, 1875 indicates that Leidy paid two installments of $7.50 to obtain the bodies from the gravesite. Leidy writes in the receipt that he used “connivance” to get the bodies he so desired.

Solving the Mystery of Mrs. Ellenbogen

Leidy may have been the main instigator in acquiring the saponified bodies but he was by no means the sole perpetrator of nefarious activity. According to the receipt from Leidy, The College reimbursed him for his expenses in obtaining the Soap Lady. But it was not until after Leidy’s death that Dr. William Hunt published a detailed account of how Leidy was able to obtain the two bodies. Hunt was a member of the Mütter Museum Committee from 1865–1895 and was the acting curator at the time of the Soap Lady’s acquisition. In an article published January 16, 1896, in the Philadelphia Public Ledger Hunt states:

The only instance I ever know of Dr. Leidy’s departure from strict truth was, to a medical man’s way of looking at it, a very amusing one. Some years ago he came to my house in quite an enthusiastic mood, and said: ‘Doctor Hunt, do you know that they are moving the bodies from a very old burying ground down town to make way for improvements?’ ‘Yes,’ I said ‘Well’ he went on, ‘two bodies turned into adipocere are there…They have been buried for nearly a hundred years, nobody claims them, and they would be rare and instructive additions to our collections.’ ‘Alright; [said Hunt] I shall be delighted.’

So Leidy went down to secure the prize. When he spoke to the Superintendent, that gentleman put on airs, talked of violating graves, etc.; so the discomfited doctor was about to withdraw. Just then the Superintendent touched him significantly on the elbow and said: ‘I tell you what I do, I give bodies up to the order of relatives.’ The doctor took the hint, went home, hired a furniture wagon, and armed the driver with an order reading: ‘Please deliver to bearer the bodies of my grandfather and grandmother.’ This brought the coveted prizes and the virtuous caretaker was not forgotten.

They were not Leidy’s grandparents, they did not die in 1792, and their name was not Ellenbogen. McFarland may have solved one mystery but he created many more. The Mütter Museum now had the body of an unidentified woman.

In 1987 a team headed by Gerald Conlogue, then at Thomas Jefferson University, conducted a radiographic examination of the Soap Lady. (See Beckett interview in this issue; Conlogue is now Beckett’s research partner.) They brought a portable x-ray unit to the museum and made some interesting discoveries. Even though she was toothless and appeared elderly, her skeleton was healthy, robust, and showed no signs of degeneration due to aging. They estimated her age to be around 40. However, due to the remodeling of the bone in her jaws she probably lost her teeth many years before her death. Her jaw was also broken on both sides but the fracture pattern and lack of healing suggested a probable post mortem trauma. In addition the team also found eight straight pins around her body. The pins were in areas that seemed to indicate they were used to secure a shroud around her body at the time of death. These pins also provide material evidence to support that the 1792 date of death is false, as the pins were made by a machine that was patented in England in 1824.

Conlogue and his team reunited in 2007 to take another series of x-rays, this time using a different, more sensitive machine. The quality of the images was much better, enabling a physical/forensic anthropologist to reassess the age of the Soap Lady. We now think she was in her 30s when she died.

This new information, while interesting, does not answer the main questions surrounding our mysterious Soap Lady: who was she and how did she die? In order to possibly identify her and determine her cause of death we need to conduct further testing. This will not be easy due to the fragile nature of her body. The adipocere has a crumbly texture and will flake off in large chunks if she is mishandled. We are evaluating the DNA potential of some hair follicles and nail samples for sufficient and viable material to conduct an analysis. Her new younger age assessment also raises the question of the nature of her tooth loss. She probably lost all her teeth by her teens or early twenties. While it is possible this tooth loss occurred via general lack of dental hygiene, there may have been an underlying pathological condition. We also plan to test her hair for the presence of heavy metals or other poisons/contaminates that may have exacerbated the tooth loss.

Perhaps after more than 140 years we can finally solve the mystery of the Soap Lady. She has quietly endured much opinion and speculation since her arrival. While we may never be able to put an actual name to her gaping face, we may be able to say, with some degree of certainty, how she died, how old she was at the time of death, and perhaps, how she came to lose all her teeth so early in life.

Anna N. Dhody is the Director of the Mütter Institute and the Curator of the Mütter Museum.