“Cursed be those that disturb the rest of Pharaoh. They that shall break the seal of this tomb shall meet death by a disease which no doctor can diagnose.” (Inscription reported to have been carved on an Egyptian royal tomb)

Throughout the centuries, ancient Egypt and its civilization have often been referred to in terms of the dark and mysterious. Encounters with its strange customs have frequently led people, both ancient and modern, to have misconceptions about this land. The Greeks acknowledged that much ancient wisdom, such as the basics of mathematics, architecture, art, science, medicine, and even philosophy, ultimately derived from the Egyptians; but they still had some difficulty in understanding, accepting, or even dealing with the alien and unfamiliar aspects of the religion. Greek historians often wrote about the mysterious ways in which the Egyptians worshipped their deities, such as this note by Herodotus: “There are not a great many wild animals in Egypt…Such as there are—both wild and tame—are without exception held to be sacred” (II, 65). He also wrote a disclaimer: “I am not anxious to repeat what I was told about the Egyptian religion. . . for I do not think that any one nation knows much more about such things than any other” (II, 4). Of course he then goes on to state: “[The Egyptians] are religious to excess” (II, 35-39).

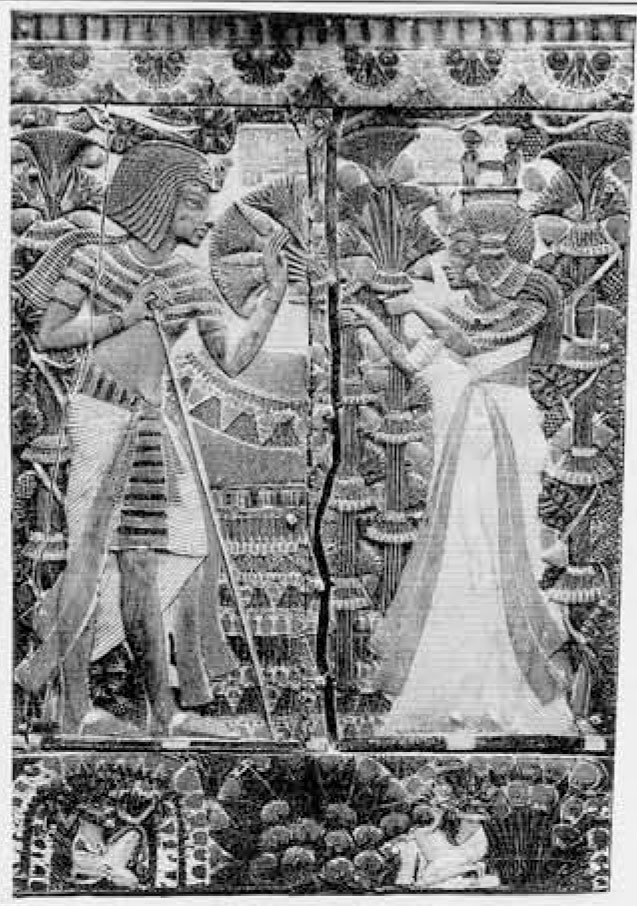

Egypt was different from much of the rest of the ancient world, with its pantheon of fantastic deities, part animal, part human; its rulers who were understood to be gods on earth; its bizarre funerary practices that paid unheard of attention to the preparations for an afterlife; and its enigmatic script that was written with recognizable pictures, but remained unreadable and therefore mysterious to the uninitiated. As a result, Egypt managed to inspire both awe and fear in the foreigner who came into contact with its culture.

Today, the products of Egyptian civilization that have survived the passage of more than 3000 years provide a visible monument to its advanced state. Such accomplishments, however, often evoke suspicion rather than respect. Thus there are people who prefer to believe that Egyptian building techniques, literature, art, and mathematics derived from an alien culture from outer space, rather than to accept the documented evidence of their earthly origin. This and other equally inaccurate theories are espoused by people fondly referred to by Egyptologists as “pyramidiots.” But while some modern ideas about ancient Egypt are based on a mixture of misguided awe and respect, others appear to have originated under less innocent circumstances. One of the most persistent examples of the latter type is the so-called curse of the pharaohs.

An Egyptologist Cursed

During the last hundred years or so, the phrase “curse of the pharaohs” has been used to describe the cause of a large assortment of ills. These range from natural disasters to a mild stomach disorder that often plagues tourists to Egypt (also known as “pharaoh’s revenge,” or “gippy tummy”—derived from “Egyptian tummy”). I became personally involved with this curse (I mean that supposedly written by or for the pharaohs), when I became Project Egyptologist for the Treasures of Tutankhamun Exhibit that traveled across the United States from 1976 to 1979.

Charged with writing the text that appeared in the exhibit, I conducted research on all aspects of the discovery, excavation, and recording of Tutankhamun’s tomb and its contents. Naturally, I came across several references to the famous “curse of King Tut.” But before I had begun to deal with that matter on more than a superficial level, I came into contact with the “curse of the curse of King Tut.” My first published newspaper interview consisted of a few descriptive paragraphs about the exhibition that carried this headline: “Beware the beat of the bandaged feet, as the ancient Egyptian saying goes.” Of course there was no such saying in ancient Egypt. I vowed that the next time that I met with a reporter I would be more careful: I had to be assured that the tone of the column would be as professional as possible and the content totally accurate.

Within a matter of weeks I was interviewed again, when the crate containing Tutankhamun’s funerary mask was opened. I was circumspect, cautious, and at my scholarly best. Moreover, the entire discussion was taped; this way, I thought, I would be sure that the real facts behind the curse of King Tut were included, and any misunderstandings avoided. Afterward I waited expectantly for the newspaper to appear. The front page was as accurate as I could have hoped, but on the follow-up, the headline read: “Egyptologist admits there was a curse.” In fact, this line did bear some relationship to what I had said. In discussing the deaths of those associated with the tomb of King Tut I had remarked: “It is true that everyone who enters the tomb will die, just as it is true that everyone who crosses Woodlawn Avenue (a main thoroughfare on the University of Chicago campus) will eventually die.” I never expected to have my remark edited in such a creative way and taken out of context.

While this kind of misinformation may seem innocuous enough, there were several other articles that gratuitously included unsubstantiated “facts”, such as that which appeared in the Washington Post (March 16, 1977): ” ‘Cursed be those that disturb the rest of the pharaoh’ read an inscription on his tomb.” There was in fact no curse on either the walls of the tomb or on any object found inside it. So, you may well ask, If there was no curse, how is it that there are so many of them attributed to the tomb and its owner? In the case of the articles written during the latest King Tut exhibit, I venture to say that most if not all references to the curse derived from ignorance and a desire for a catchy headline—not necessarily in that order.

The Troubles of Carter and Carnarvon

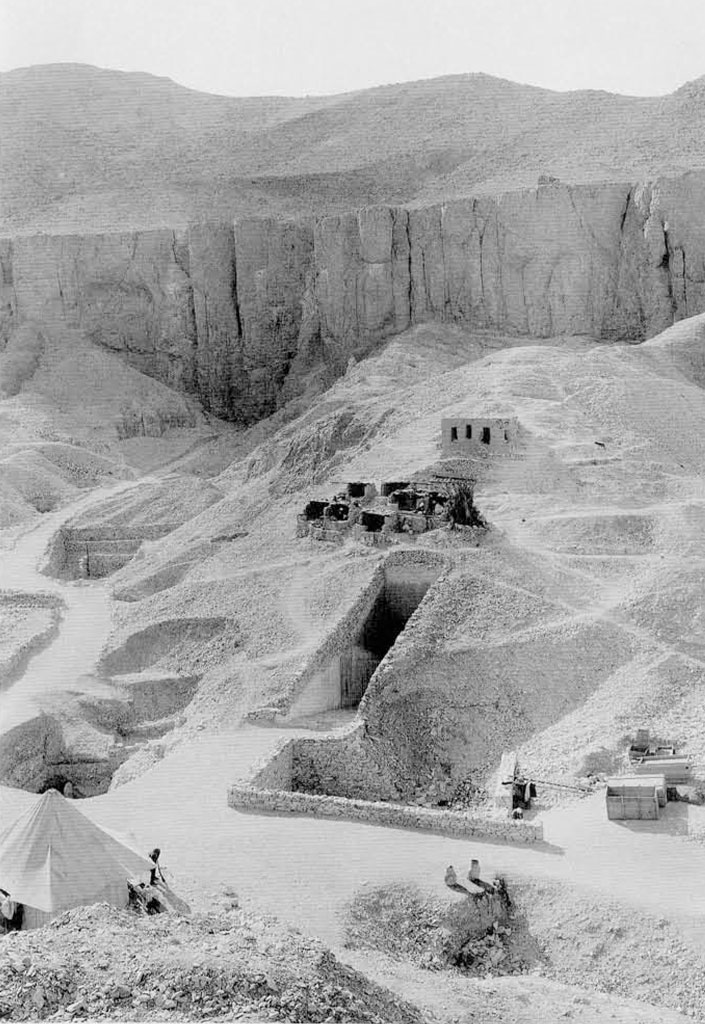

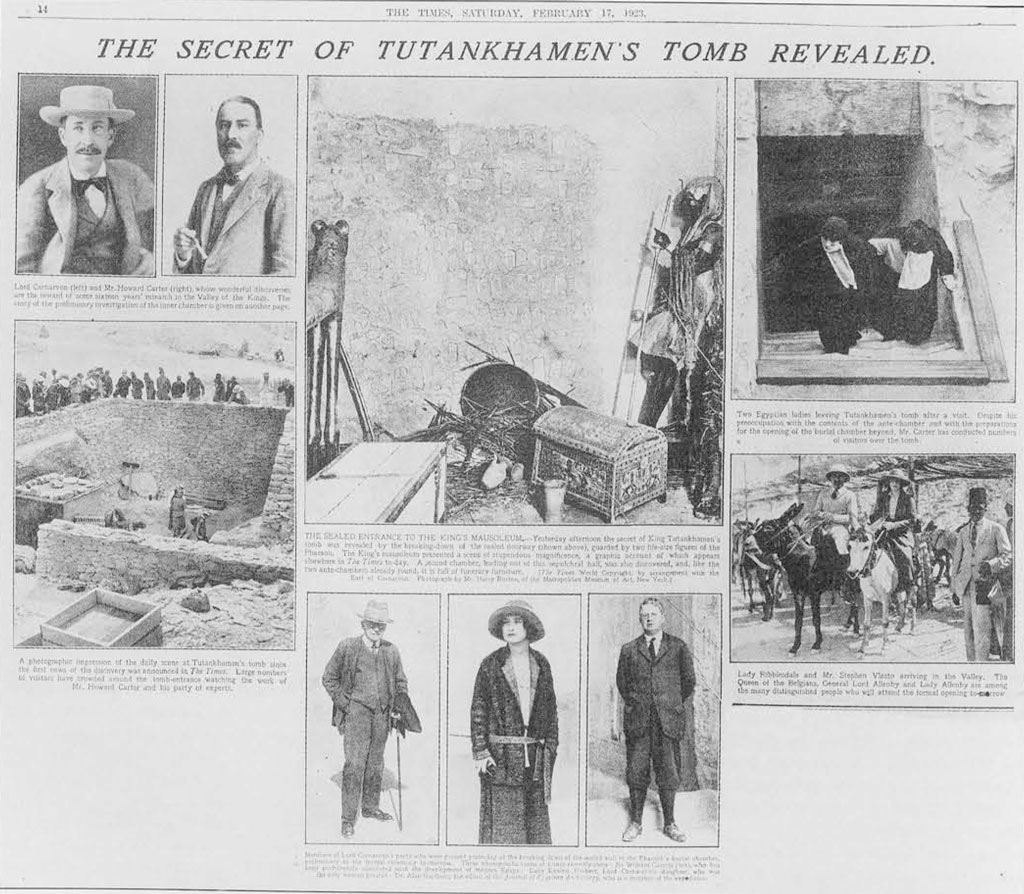

From the time of the discovery of the young pharaoh’s tomb in 1922 it was surrounded by controversy. The original concession granted to the excavators by the Egyptian government called for some division of the finds between the host country and the excavator, as had been the custom in the past.

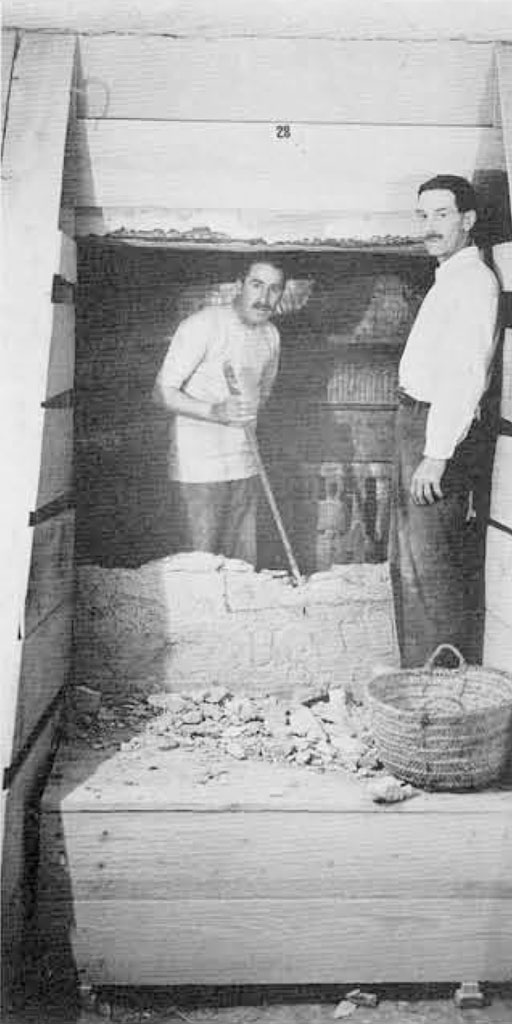

In the end, such a division was precluded, primarily because of the desirability of keeping together the contents of a nearly intact tomb that was such an important part of the heritage of the country, not to mention the magnitude of the discovery, its impact on the world, and its effect on our knowledge of the past. While Lord Carnarvon, the sponsor of the expedition, hardly needed nor indeed expected vast remuneration for his archaeological efforts, there was the question of the cost of six years of field work conducted for Carnarvon by Howard Carter before the tomb was discovered. Moreover, there were six and one-half more years of work ahead in order to clear the tomb, and then four years of work to be completed in the laboratory before the last of the artifacts would leave the Valley of the Kings for the Cairo Museum.

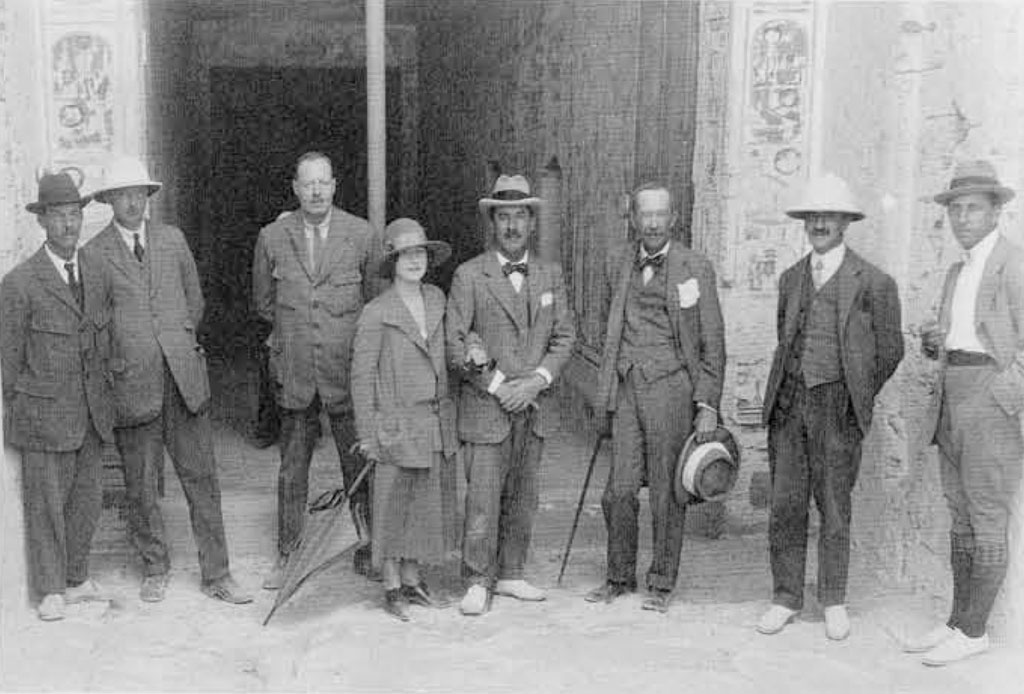

In a stunning move that was calculated to deal with all of his problems (not the least of which was the overwhelming demand for information from the press), Lord Carnarvon sold the exclusive rights to publish anything about the tomb to the Times of London. By this action, Carnarvon was able not only to offset the costs of previous and future work at the site, but also to avoid constant interruptions by the press. In the past, members of the expedition had been badgered to utter distraction by reporters hungry for stories about an event that had aroused the interest of the public; now, reporters no longer had direct access to such sources. This is not to say that the Times withheld all information: it did give out stories—but only after they appeared in the Times, with the result that all other newspapers were always at least a day behind the Times with any news about the boy king.

This situation angered the press, but they were not the only ones who were disgruntled. In an effort to keep tourists from interrupting those who were trying to record and clear the tomb, Carter and Carnarvon had barred virtually all but a select few from the excavation. Some officials of the Antiquities Service, other Egyptologists, and political figures from Egypt and around the world could not gain access to the tomb easily. Such secrecy caused rumors to flourish, the most malicious of which referred to the planned theft of some objects. Unfortunately, there may well have been a bit of truth to these stories, and some authors claim that a few artifacts now in the collections of museums outside Egypt may have originated in Tut’s tomb!

Conversely, one of the objects that remained in the collection and is now on exhibit in the Cairo Museum may not have come from its designated find spot. A head of Tutankhamun portrayed as the god Nefertem emerging from a lotus depicts one of the ancient creation myths. According to Carter’s later published reports, it was found in the corridor to Tut’s tomb; this location, however, really did not make much sense, since all similar objects were found in the Treasury. Carter did not include any real information about the head in his original field reports, nor did he note it in the first volumes of his book. In fact, the figure was “discovered” in a neighboring tomb (used for storage) when a committee of officials visited the site during Carter’s absence. It was carefully wrapped, and stored in a crate with labels from a European provision shop. Despite these irregularities, no scandal emerged, and the apparently hastily devised version of its origin has become the official story: it was found in debris in the corridor, where it had been left by (ancient) thieves.

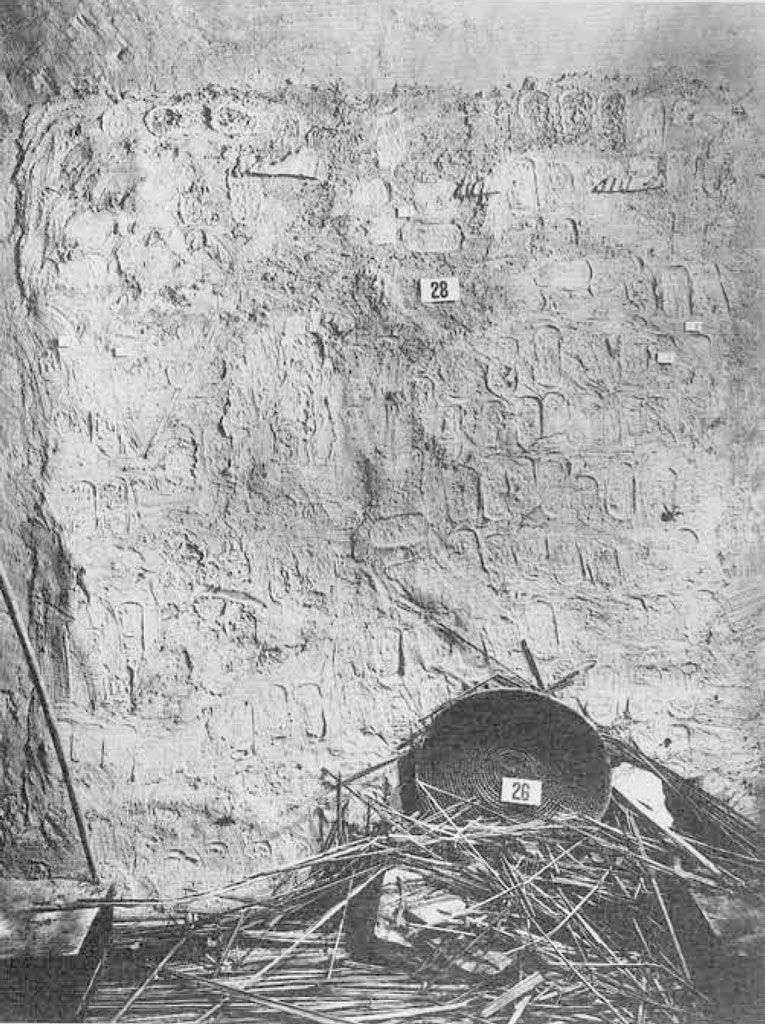

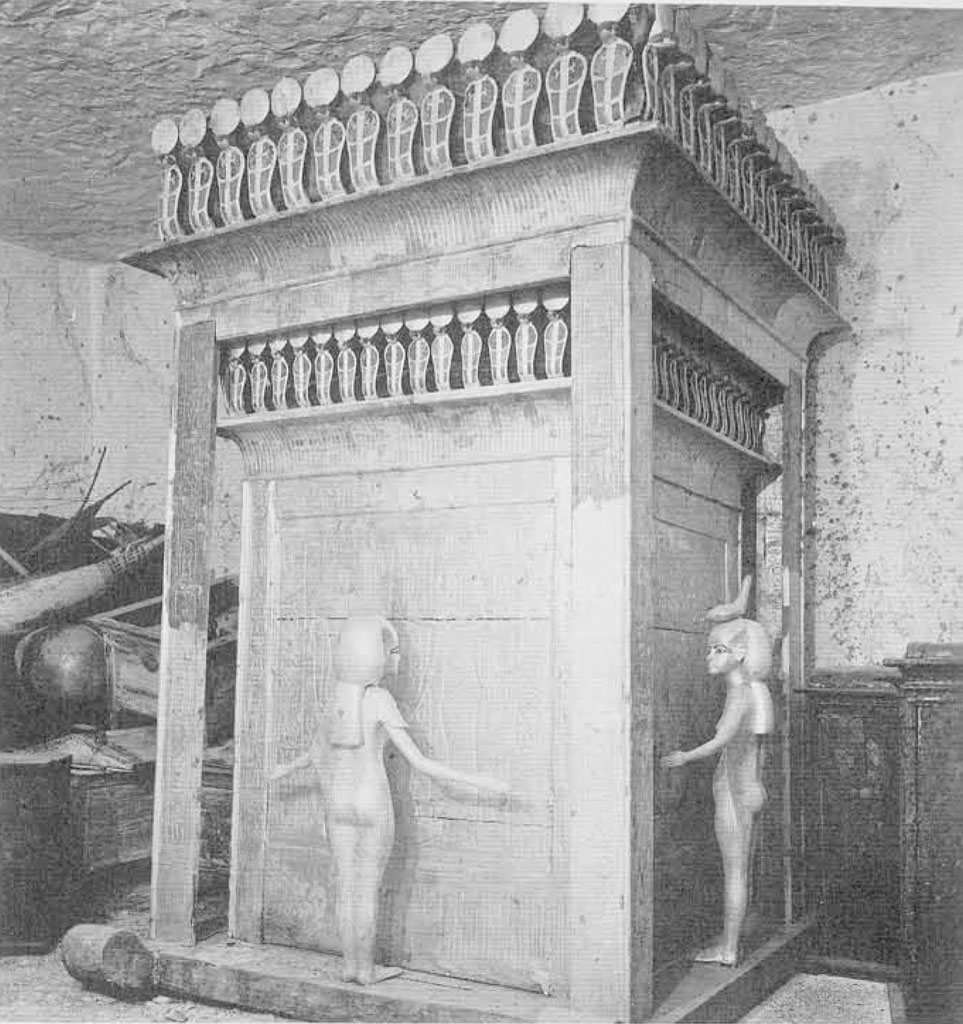

While the media missed out on this particular episode, they did have a field day when Lord Carnarvon died on May 6, 1923—less than a year after the discovery of the tomb. There were all sorts of versions of the specific “curse” to which Carnarvon’s death could be attributed, but most tried to relate it to an inscription of warning in the tomb. Some of the reporters had the aid of disgruntled Egyptologists, who had not only been denied access to the tomb, but also any information about it. Since there was no love lost between Carter and Carnarvon and some of their scholarly colleagues, there was always someone who was willing to provide information about certain objects or inscriptions in the tomb, based solely on published photographs. In this manner, many inscriptions could be construed as curses by the public, especially after a “re-translation” by the press. For example, an innocuous text inscribed on mud plaster before the Anubis shrine in the Treasury stated: “I am the one who prevents the sand from blocking the secret chamber,” In the newspaper, it metamorphized into: “…I will kill all of those who cross this threshold into the sacred precincts of the royal king who lives forever.”

Such misrepresentation proliferated, and soon curses were being found in all of the inscriptions. Since few people could read the texts and thereby check the original, the reporters were safe. They could (and did) publish a photograph of the large golden shrine in the Burial Chamber, together with a “translation” of the accompanying inscription: “They who enter this sacred tomb shall swift be visited by wings of death.” The carved figure of a winged goddess that accompanied the shrine would no doubt reinforce the “translated” threat. In reality, the texts on this shrine come from The Book of the Dead—a collection of spells intended to ensure eternal life, not to shorten it!

Poor Lord Carnarvon. His death, rather than promoting the peace and quiet that he wished for himself and his colleague Howard Carter, resulted in more interest in, and scandal and intrigue about, the discoverers of King Tut. Every newspaper around the world carried a story about Lord Carnarvon’s death from the mysterious and ominous forces unleashed from the tomb that he was responsible for opening. All sorts of related phenomena were also attributed to the action of the curse upon the defiler of the tomb. For example, all the lights in Cairo were reported to have gone out at the precise moment of Lord Carnarvon’s death. The loss of electricity in Cairo; however, was not an uncommon occurrence, and is an experience that most tourists to Egypt have encountered several times.

Carnarvon’s son, Lord Porchester, added to the mystery by recounting that his father’s dog, at home at the family castle Highclere, let out a pitiful cry at the moment of its master’s death, and then it too died. It appears, however, that Lord Porchester was in India at the time of his father’s death, so the story of the dog’s demise must have been related to him, not actually seen by him. It is pertinent to note that the estate of the deceased Lord Carnarvon continued to reap the benefits of the arrangement made with the Times of London, receiving a percentage of the profits realized from the sale of stories. Keeping the interest of the public at fever pitch was a lucrative business for both the Times and Carnavon’s estate. During the Chicago portion of the recent exhibition (April 15-August 15, 1977), Lord Carnarvon’s heir stated that although he did not know if there was a curse, he wouldn’t take one million pounds to enter the tomb. The real story behind the death of Carnarvon is not quite so dramatic, if no less tragic. It appears that he died of an infection that caused blood poisoning, and that the origin of this infection was a mosquito bite on the cheek, cut open by a razor during shaving.

Corroboration for Tutankhamun’s curse mounted as people died who could be associated in some way with Carnavon or with the tomb. More rational explanations of these deaths were overlooked by the reporters, who could finally get a scoop and not have to wait for the Times to present their facts. Throughout the world, the story of the death of Carnarvon was recounted in detail, though not necessarily with accuracy. The press began to have a field day after the death of Carter’s conservator (A.C. Mace of the Metropolitan Museum of Art); the fact that Mace had had pleurisy for a long time did not appear to affect the storytellers. So another man fell to the curse. A friend of Carnarvon’s who was infirm and elderly was the next to succumb. Then the Egyptologist, archaeologist, and writer Weigall (whom Carter and Carnarvon had attempted to keep out of the tomb under any circumstances) died too, supposedly from the curse. An Egyptian prince was murdered in London by his jealous French wife–another victim! Soon the papers carried stories of curators and workmen from museums all over the world, who had neither visited the tomb nor come into close contact with any of its contents, but had nevertheless been struck down. Nervous people began cleaning out their basements and attics and sending their Egyptian relics to museums in order to avoid being the next victim.

Times have not changed. About 15 years ago, the Director General of the Egyptian Antiquities Department (Dr. Gamal Mehrez) died; he had been chronically ill, but his death was attributed to the movement of King Tut’s treasures for an exhibition in England. Even more recently, I had to testify for the prosecution at the trial of a man who had murdered his wife because (the defense claimed) he had been cursed by an Egyptian object that had come into the couple’s possession.

Carter, it should be noted, died in bed of natural causes at the age of 67 (March 2, 1939), more than 17 years after he discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun.

Some Real Egyptian Curses

All of the fabrications and exaggerations described above neglect two points. The first is that there may well have been some natural phenomena in Tut’s tomb (or any tomb, for that matter) that could cause disease, for example, molds or spores. It is a fact that paleopathologists and microbiologists now suggest that mummies be examined by people wearing gloves and masks to prevent the spread of any infection. Indeed, the Philadelphia Inquirer recently ran an article on this topic, entitled “Thesis: Fungi, not a curse, killed the finders of King Tut’s Tomb” (July 30, 1985). Of course, this theory does not account for Carter’s remarkable resistance to the micro-organisms, not to mention the workers and scientists attached to the project, officials, and tourists who also survived.

The second point is that the ancient Egyptians did in fact use curses. Most of them are couched in the form of threats, and they occur mainly on the monuments of private citizens rather than on those of royalty (see box). This interesting observation may indicate that royalty had protection against its enemies through other sources. In fact, most of the curses come from inscriptions on the walls of private tombs of the Old Kingdom, during a time when the royal tombs (pyramids) were decorated with a set of spells called Pyramid Texts that were meant as aids, advice, and directions for the king. Because of their size, prominence, and the existence of a large group of priests attached to the funerary complex, the royal funerary monuments obviously had the protection they needed.

Royal curses, when they do occur, are directed more toward this life than the next. There is an address at Deir el Bahri by Thutmose I to the court of his daughter, the reigning pharaoh Hatshepsut: “He who will adore her, he will live; he who will speak evil in a curse against her majesty, he will die” (Sethe 1906:15 ff). Somewhat distinct are the “execration texts” that occur on pottery bowls and figurines from the end of the 12th-13th Dynasty. These are curses against foreign states or peoples that might act or had already acted against Egypt. At appropriate times, the objects with their curses were ritually smashed.

Amenhotep, son of Hapu, was a remarkable figure from the 18th Dynasty, who was later deified (in the 21st Dynasty). A mortuary temple which was built in his honor was protected by a rather lengthy and detailed curse:

“As for [anyone] who will come after me and who will find the foundation of the funerary tomb in destruction…

as for anyone who will take the personnel from among my people…

as for all others who will turn them astray…

I will not allow them to perform their scribal function…

I will put them in the furnace of the king…

His uraeus will vomit flame upon the top of their heads, demolishing their flesh and devouring their bones.

hey will become Apophis [a divine serpent who is vanquished] on the morning of the day of the year.

They will capsize in the sea which will devour their bodies.

They will not receive honors received by virtuous people. They will not be able to swallow offerings of the dead.

One will not pour for them water in libation…

Their sons will not occupy their places, their women will be violated before their eyes.

Their great ones will be so lost in their houses that they will be upon the floor…

They will not understand the words of the king at the time when he is in joy.

They will be doomed to the knife on the day of massacre…

Their bodies will decay because they will starve and will not have sustenance and their bones will perish” (British Museum Stele 138; Varille 1968).

Important decrees could also be protected by threats, especially in regard to specific individuals already proclaimed guilty, as this indictment shows:

“As to any king and powerful person who will forgive him, he will not receive the white crown, he will not raise up the red crown, he will not dwell upon the throne of Horus of the living. As for any commander or mayor who will petition my lord to pardon him, his property and his fields will be put as offerings for my father Min of Coptos” (Sethe 1959:98, 16ff).

It is clear that while the Egyptians rarely made the kind of curses that you find in the headlines, they did understand the power of negative thinking and saying. Their curses are hardly a mystery, hardly an enigma. Their suggestive remarks and threats were meant to dissuade those who might act against them. The means by which this was accomplished was the written word, so important in all aspects of Egyptian culture. The curse would survive as long as the monument on which it was written.

Edel, Elmar

1944

“Untersuchungen zur Phraseologie der agyptischen Inschriften.” Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archaologischen Instituts, Abteilung (Koko) 13:1-90.

Gardiner, Alan

1940

“Adoption Extraordinary.”,Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 26:23.

Gardiner, Alan H., and Kurt Sethe

1928

Egyptian Letters to the Dead. London: Egypt Exploration Society.

Griffith, F.L.

1898

Hieratic Papyri from Kahun and Gurob. London: Bernard Quaritch.

Helck, Wolfgang

1975

“Flush.” Lexikon der Agyptologie 2, Lieferung 2. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

Herodotus

1954

The Histories. Tr. Aubrey de Selincourt. Reprint. Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1965.

Hoving, Thomas 1979

Tutankhamen, the Untold Story. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Sethe, Kurt

1906

Urkunden der 18. Dynastie. Urkunden des agyptischen Altertums IV. Leipzig: J. Hinrichs.

1959

Agyptische Lesestticke. Hildesheim: Georg Olms.

Spiegelberg, W.

1903

“Die Tefnachthosstele des Museums von Athen.”Recueil des Travaux 25:191-192,

Vandenberg, Phillipp

1975

The Curse of the Pharaohs. Tr. Thomas Weyr. Philadelphia: J. Lippincott.

Varille, Alexandre

1968

Inscriptions concernant farchitecte Amenhotep fits de Hapu. Bibliotheque d’Etudes 44. Cairo: Institut Francais d’Archeologie Orientale.