The old chief, seventy-five years old by the calendar of the Europeans, two Sigis and ten years by the calendar of his people, the Dogon, leaned against the sun-warmed rose-pink wall of his house in the village of Sanga, province of Bandiegara, free Republic of Mali. Soon, in five months, would come the celebration of Sigi, the long (three months’ long) festival in honor of the tribal ancestors, held every sixty years, when participants must learn the secret language of Sigi, and the life force of all members of the tribe would be renewed and strengthened by songs and dances and special feasts. He could vaguely remember the Sigi he had known when he was a boy of fifteen, the year of his circumcision. Then, after consultation with many of the Dogon elders in other villages, an uncertain rule of procedure for the celebration had been worked out.

The old chief, seventy-five years old by the calendar of the Europeans, two Sigis and ten years by the calendar of his people, the Dogon, leaned against the sun-warmed rose-pink wall of his house in the village of Sanga, province of Bandiegara, free Republic of Mali. Soon, in five months, would come the celebration of Sigi, the long (three months’ long) festival in honor of the tribal ancestors, held every sixty years, when participants must learn the secret language of Sigi, and the life force of all members of the tribe would be renewed and strengthened by songs and dances and special feasts. He could vaguely remember the Sigi he had known when he was a boy of fifteen, the year of his circumcision. Then, after consultation with many of the Dogon elders in other villages, an uncertain rule of procedure for the celebration had been worked out.

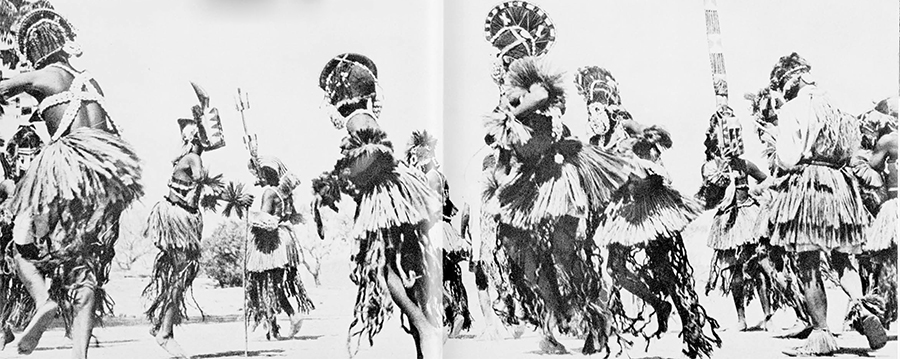

First, there was the secret language in which the chants of Sigi must be sung. The old men, in the past few months, meeting in their sacred shelters, old stone-floored squares, roofed with thick thatch of millet straw, had managed to recall many of the songs and had taught them to the young men and the drummers, so that the dancers of the four age groups — children, circumcised boys, young men, and old men—could rehearse their marches and dances, both as groups and as solo performers. These rehearsals were held in many of the little villages perched on the rocks of the big province and with groups of old men as judges, it had been decided that Ibi village, close to Sanga, should be the site of Sigi of 1969, sixty years after the celebration of the 10th Sigi.

First, there was the secret language in which the chants of Sigi must be sung. The old men, in the past few months, meeting in their sacred shelters, old stone-floored squares, roofed with thick thatch of millet straw, had managed to recall many of the songs and had taught them to the young men and the drummers, so that the dancers of the four age groups — children, circumcised boys, young men, and old men—could rehearse their marches and dances, both as groups and as solo performers. These rehearsals were held in many of the little villages perched on the rocks of the big province and with groups of old men as judges, it had been decided that Ibi village, close to Sanga, should be the site of Sigi of 1969, sixty years after the celebration of the 10th Sigi.

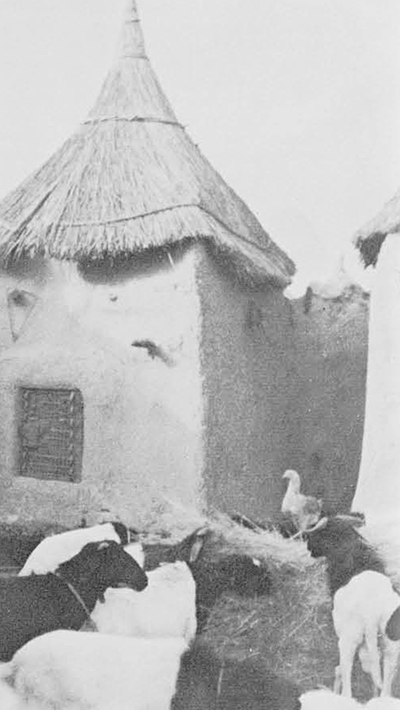

Next in importance after the songs and the dances honoring the Great Mask—it was 18 feet long and hidden safely in a secret sacred cave known only to the great Old Men—came the costumes of the dancers. The old man scratched his grizzled head. It was hard for him to recollect the details of the costumes. He got up off the old stool on which he was sitting, a “royal” stool, carved out of hard black wood by the village blacksmith, the forgeron, who also made the dance staffs, the carved figures for the ancestor shrines and the strange little portable seats, like the Europeans’ shooting sticks, used by the Sigi dancers. He pulled over to him the notched log that served as a ladder to the roof of his house and the granary beside it. Before he climbed up, he admired the carved door of his granary, of the same hard wood as his stool and as the masks. It had a good lock, recalling the tribal ancestors, and rows and rows of small people, a family tree in miniature. On his roof, where he often slept for coolness, he made a nest for himself of the clean soft millet straw. The same straw made the thatched roof of the granary now filled with millet and a little corn and some precious dried onions.

Next in importance after the songs and the dances honoring the Great Mask—it was 18 feet long and hidden safely in a secret sacred cave known only to the great Old Men—came the costumes of the dancers. The old man scratched his grizzled head. It was hard for him to recollect the details of the costumes. He got up off the old stool on which he was sitting, a “royal” stool, carved out of hard black wood by the village blacksmith, the forgeron, who also made the dance staffs, the carved figures for the ancestor shrines and the strange little portable seats, like the Europeans’ shooting sticks, used by the Sigi dancers. He pulled over to him the notched log that served as a ladder to the roof of his house and the granary beside it. Before he climbed up, he admired the carved door of his granary, of the same hard wood as his stool and as the masks. It had a good lock, recalling the tribal ancestors, and rows and rows of small people, a family tree in miniature. On his roof, where he often slept for coolness, he made a nest for himself of the clean soft millet straw. The same straw made the thatched roof of the granary now filled with millet and a little corn and some precious dried onions.

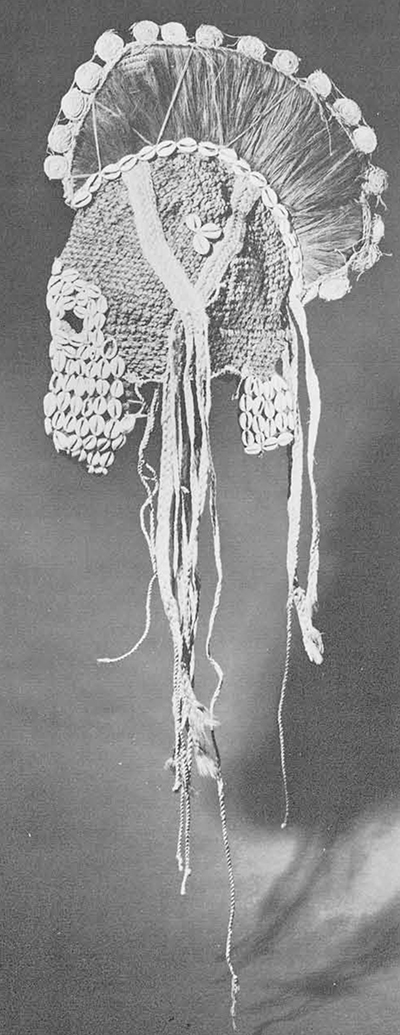

It was comfortable up there on the roof and agreeably breezy. He could see the great escarpment rising behind him, pockmarked with small caves, and plastered with more sunbaked mud granaries, safe from raids of the West African Fulani, who sometimes drove their thin cattle through his valley. And now he remembered, his thin black hands brushing the cobwebs from his old brain. The masks, the old masks of the last Sigi, are buried in that cave by the cemetery, high up on the cliff. The old man knew that little of the cloth and the raffia of the costumes could be left—there had been many springs of hot rain and fogs and many dry cool winters to rot them. But he knew the cowrie shells would be there and some of the wooden masks. The sacred cave was too inaccessible to have been robbed by the anthropologists of many nations who wanted his people’s masks and carvings for their “museums,” whatever they were.

He would buy white muslin in the markets for the women to embroider with cowrie shells and make into suspenders for the dancers. This was a job for the women. Their only function in Sigi was to make the costumes and embroider them with shells and to dress their men. He must get raffia also for the shell trimmed masks and hoods of certain of the dancers. Many skeins of soft raffia would be needed for this and already he had the children of the tribe at work on this material. So many grasses were called raffia, and in this part of the country, it was the millet, the grain of which was made into the meal which was the staple food of the Sudan, boiled into a mush.

To use it for crocheting or knitting, the long stalks were hammered with a mallet, dried and worked with the hands until soft and pliable. The old man descended his ladder, entered his house and reappeared with a calabash of palm wine. Standing in the sun, leaning on the door jamb he refreshed himself. All his problems now were solved, he climbed his ladder and lay down again to sleep in the soft straw and dreamed of Sigi.