Or ever the silver cord be loosed, or the golden bowl be broken,

or the pitcher be broken at the fountian,

or the wheel broken at the cistern.

Then shall the dust return to the earth as it was:

and the spirit shall return unto God who gave it.

Vanity of vanities, saith the preacher;

all is vanity.

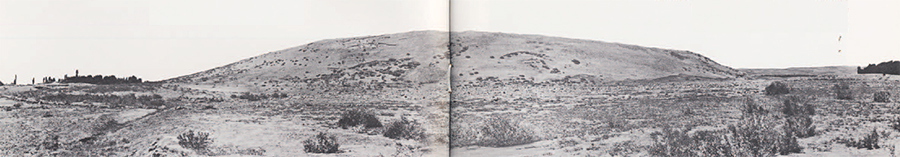

The plains and mountain valleys of northwestern Iran are littered with the skeletons of ancient cities. They lie, great mounds of deserted earth, like sleeping turtles upon the landscape. Each contains the secret of its own life and death. Collectively, they constitute a monument to the pride and energy of their builders–a testament to their fate.

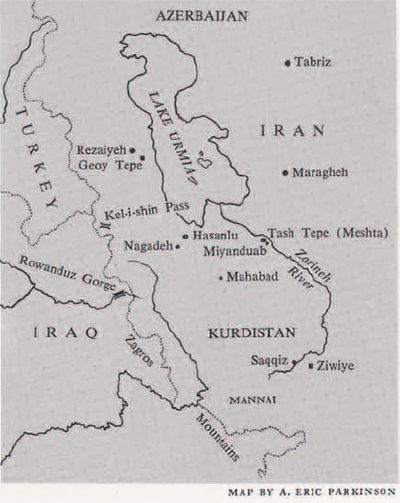

In the early Iron Age, many of these inert masses were thriving cities occupied by warriors, artisans, and farmers. The annals of Sargon II, “the great king, the mighty king, king of the universe, king of Assyria,” describe how he marched into western Iran in the eighth century B.C. and sacked “countless cities without number.” These cities, which were also periodically attacked by Urartians from eastern Turkey, were differentiated as “fortified, walled cities” and “small nearby towns.” The latter were simply looted and burned when captured; the former were also looted and burned, but in addition had their walls torn down. Those inhabitants who had not fled or been killed in battle were executed or marched off into slavery.

During the ninth century B.C. the present-day mound of Hasanlu, which dominates the northern Solduz Valley to the south of Lake Urmia, was crowned by just such a fortified citadel. With three or four sister fortresses in the area, it protected the western approach to the kingdom of Mannai which occupied the country south of the Lake. These fortress cities replaced earlier scattered villages and formed the centers of resistance to encroachments from Assyria and Urartu during the early first millennium B.C. These towns–a few private houses and a fortified citadel or castle–were the most advanced settlements in the area. They were in no way comparable to the huge metropolitan centers of the Mesopotamian plain but were, nonetheless, an important stage in the urban development of later historic Iran.

Hasanlu was one of these early towns in this development and is being excavated by a joint expedition of the University Museum and the Archaeological Service of Iran with the additional support of the Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City.

The excavations show that the entire group of structures of the Citadel belonging to the ninth century complex were laid out and built largely as a unit on a pre-existing mound of ruins. The slopes of the mound were much steeper than at present and the upper surface uneven. For the construction of the foundations, large slabs of limestone, sandstone, or metamorphic rock were hauled by wagon fifteen or twenty miles from the distant hills. Some of the slabs were over six feet in length and must have been very difficult to handle. The base of the fortification wall was leveled and, where the contours of the mound required it, stepped to follow the general mound surface. Within the walled area the regular plan of the major building so far excavated indicates that the buildings too were carefully laid out on a cleared area before construction.

Above the uncut stone foundations (which were free-standing) rose a superstructure of sun-dried mud brick set in a mud mortar. The bricks were large and square like those used in the later buildings of the Achaemenian Persians at Pasargadae, Persepolis, and Ecbatana. The dimensions indicate the stability of brick size over a period of perhaps four hundred years–a point of practical value to the archaeologist faced with the problem of dating newly found remains.

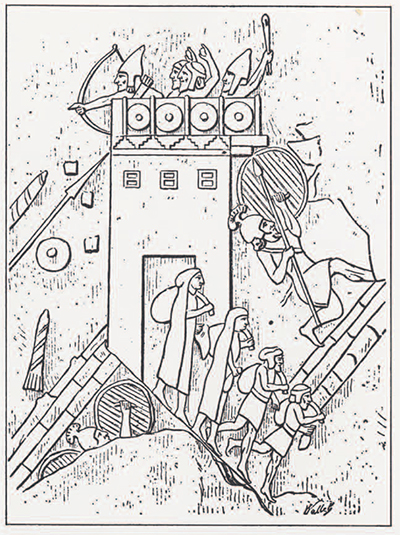

Attacks on fortified citadels of this type involved a major onset by archers against the ramparts while sappers tried to undermine the walls. Assaults by foot soldiers with ladders were also attempted. It is easy to see why people, endangered by such tactics and attacks, chose to live on the tops of old mounds and hills in the valley rather than down on the plain as they did in earlier and presumable less rapacious times.

Brickwork: Ancient and Modern

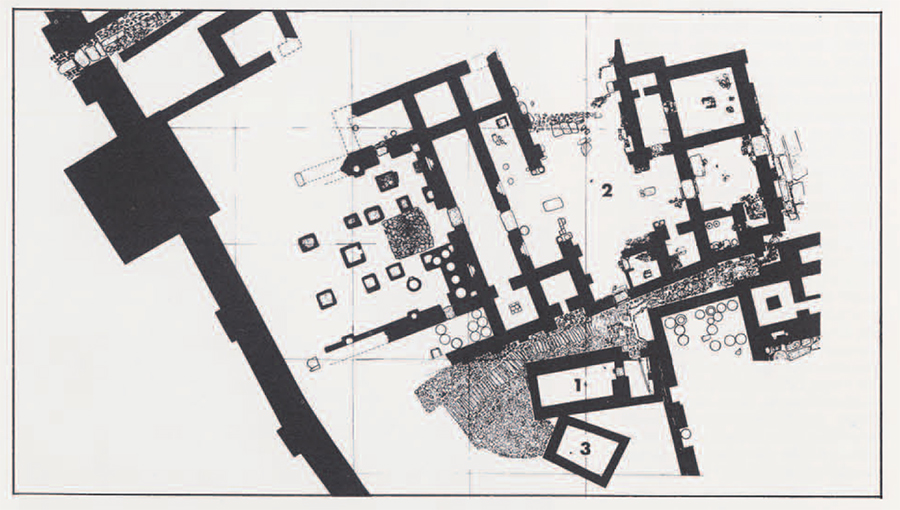

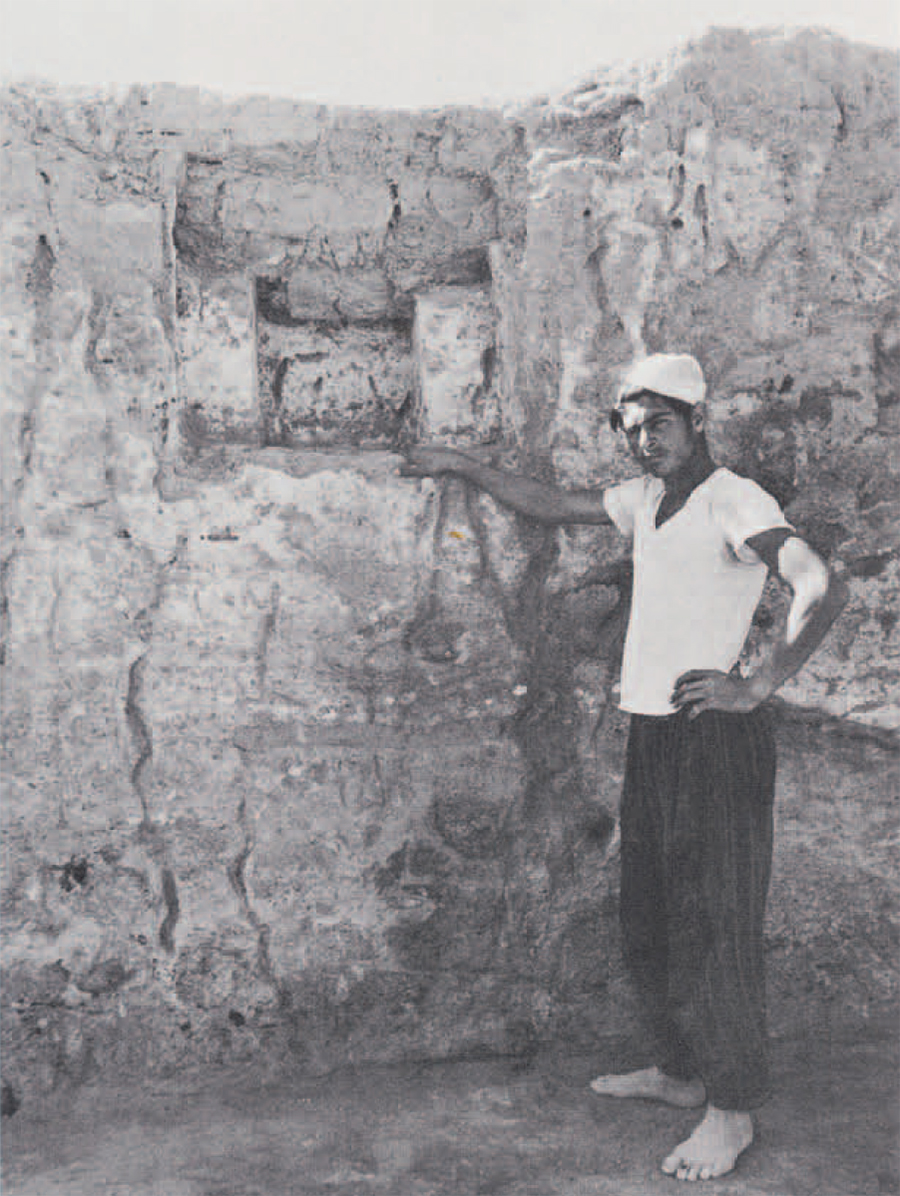

In some areas the ninth century level at Hasanlu lies beneath the remains of buildings of the historic period. In others (above) it lies virtually at the surface. The volume of collapsed brick (which preserved the lower walls) indicates a two-story structure. The wall with the stepped niche (foreground) has been exposed to half its height. The lower picture shows the palace area looking north, with walls cleared to the floor level. The two-roomed “Bead House” occupies the foreground (1) facing “South Street” which runs diagonally from left to right. Beyond lies Burned Building I consisting of a Central Court (2) with East and West Wings. Building II lies right.

Stepped niches (above) were used in some instances as decorative elements flanking doorways. In Mesopotamia such niches were often associated with religious buildings. In modern village houses, on the other hand, they are still used to house lamps. The niche and other high walls were preserved by the accidental firing which baked the brick at the time of the destruction of the fortress at the end of the period.

Village building methods reflect ancient traditions as seen above in the construction of a new room for the Expedition house. A rock foundation set in a trench (thus not free-standing) supports a wall of sun-dried brick set in mud mortar which is sometimes mixed with a little lime. The bricks are made in a wooden frame, the mud often containing ancient potshreds as well as chopped straw. Mason’s tools include string, plumbob, and trowel.

Dwellings

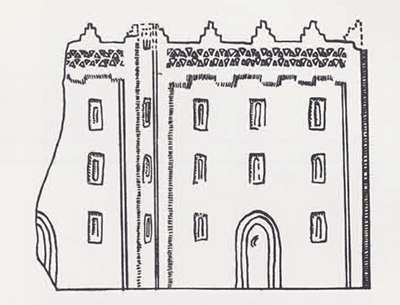

Houses of the ninth century rose to two or even three stories in height, as shown by stone reliefs (cover) and by a bronze house model from Urartu (left). The framed windows and arched doorway are typical features. Curiously, the doorways at Hasanlu contain no stones with pivot holes such as are found in Assyrian houses. Rather, as in the case of some Urartian doorways at Karmir Blur in Soviet Armenia, the doorways were provided with wooden frames. No indication of hinges has been found at Hasanlu and the method of hanging the doors is, therefore, still unknown. Nor have any remains of windows been preserved although they must have been used. Framed windows of the type seen in the model, set similarly in a recessed wall under a crenelated eave, are found in the much later Fire-temple at Naqsh-i-Rustam, burial place of the Achaemenian kings of the sixth and fifth centuries B.C. in southern Iran.

The possibility that some of the Hasanlu roofs may have been pitched rather than flat is raised by the known use of such roofs on the temple of Haldi in nearby Musasir, west of Hasanlu, and in the stone tomb of Cyrus (d. 529 B.C.) at Pasargadae.

For the adornment of inside walls at Hasanlu, Assyrian style glazed wall tiles were employed. Such tiles apparently were used sparingly, however, as only a few have been found. Simple geometric patterns in black, yellow, and white imitate more elaborate tiles in the palaces at Ashur and Nimrud. A hollow knob in the center of the tile provided a means of attachment to a wooden peg set in the wall. Rarely, this know was given human or animal form. The human head (left) is one of these and recalls with its beard and horned cap the third chariot god on the Hasanlu Bowl (Expedition 1,3, page 19), who wears a similar costume.

Defense

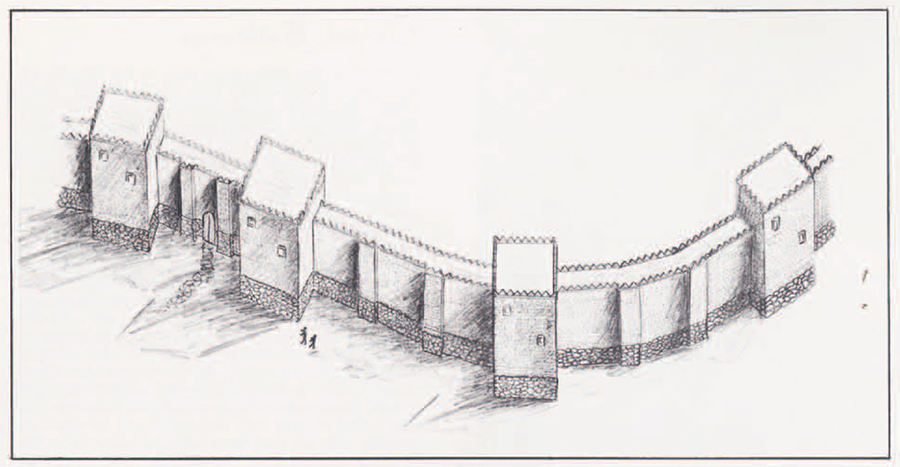

A powerful mud brick wall set on stone foundations defended the Citadel at Hasanlu. It was strengthened at intervals by stone piers set between projecting towers. The hypothetical reconstruction (above) is drawn to scale from the plan, using Assyrian reliefs of the period as a guide and basing the height of the brickwork on proportions given in the annals of Sargon of Assyria regarding walls in northwestern Iran. The full preserved height of the stone base is about eight feet, while the thickness is over nine. The probably total height would have been about thirty feet.

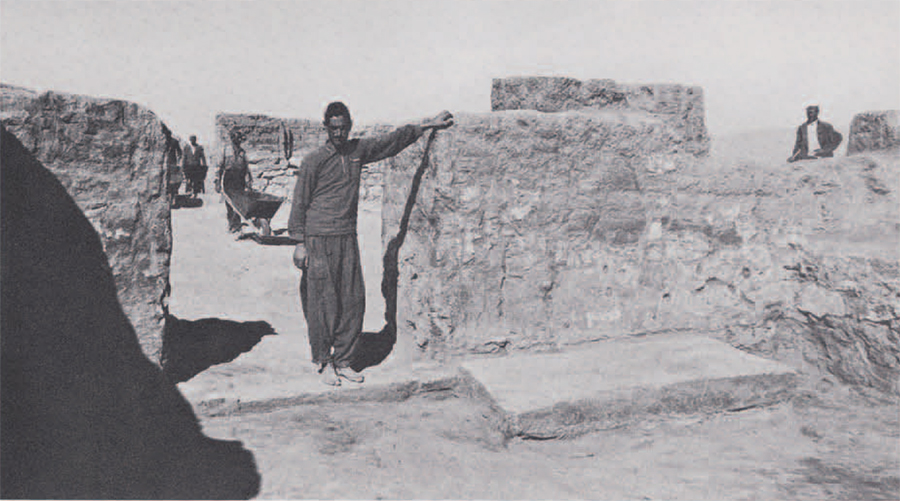

Inside the West Gate, which was paved with three large slabs (one of which has been pried up in the picture to the right), a paved street led into the central area of the Citadel. Under the street runs a stone-lined drain which passes through the gate and on down the slope of the mound. The row of trees marks the edge of the Outer Town area which lies below. The gate faces in the direction of the Zagros mountains which separate the valley from Assyria.

Citadel Buildings

Although the entire inner area of the Citadel was occupied by buildings, only those of the southwestern quadrant are at present known from excavation. The plan (below) reveals a large palace-like structure, Burned Building I (2), separated from a second partially excavated building by a paved street which appears once to have widened into a courtyard behind a tower in the fortification wall. Next to this South Street court area stood two small buildings of the single story height–the two-room Bead House (1) and the one-room South House (3). The latter contained many bowls with pointed bases while the former held many beads, broken bone “handles,” and stone bowl fragments. Next to these two buildings, which were built late in the period, stands the large storage room of another palace building running into the unexcavated area to the right. A view from that unexcavated area looking diagonally across the ruins toward the northwest is shown in the picture on the left. Large storage jars line the floor. In some instances, one jar had been stacked above another. In the background may be seen the western portico and stepped niches of Burned Building I.

The architecture, as do some of the objects, reflects the geographical position of Hasanlu at a crossroads. The use of spaced towers and intermittent piers on the Citadel wall parallels similar features at the Urartian site of Karmir Blur. The rectangular balanced plan of the main building recalls the Bit-hilani palaces of northern Syria.

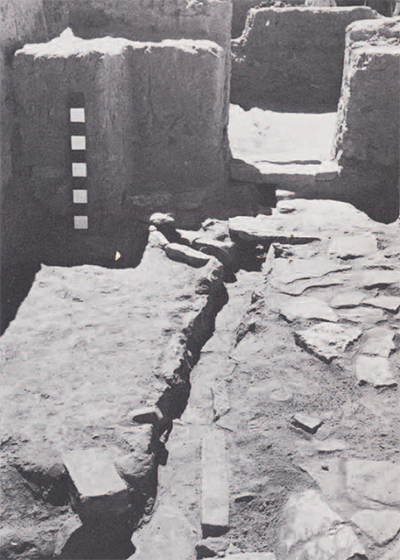

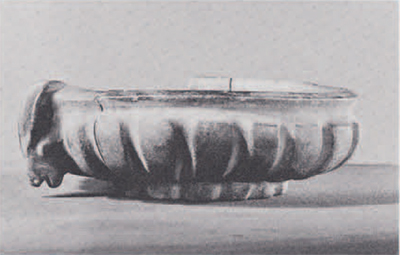

Fragments of broken stone bowls like the one shown were found in and around the Bead House, the entrance to which is seen at the right. Under the entry room of the house ran a stone-lined drain connecting the courtyard area behind the house with the street in front. The paving stones in the street have been removed to show this underlying channel. The small auxiliary channel to the left probably drained the area between the walls of the Bead House and an adjoining building.

Across the street, the main room in the east wing of Burned Building I contained an enormous slab of limestone set against the wall next to the door opening onto the portico of the Central Court. Such a stone slab may have been used as a base for a piece of furniture in the fashion of an Assyrian throne room; but as no remains of charred furniture were found in the room, its function must remain hypothetical. The doorway was framed by wood as shown by impressions in the plaster. The wall was first covered with mud plaster and then coated with white lime. Remains of such plaster and a small stepped niche may be seen on the southern wall of the room (right). No evidence of wall painting has yet come to light but there is no reason to think that such paintings did not exist.

Attack

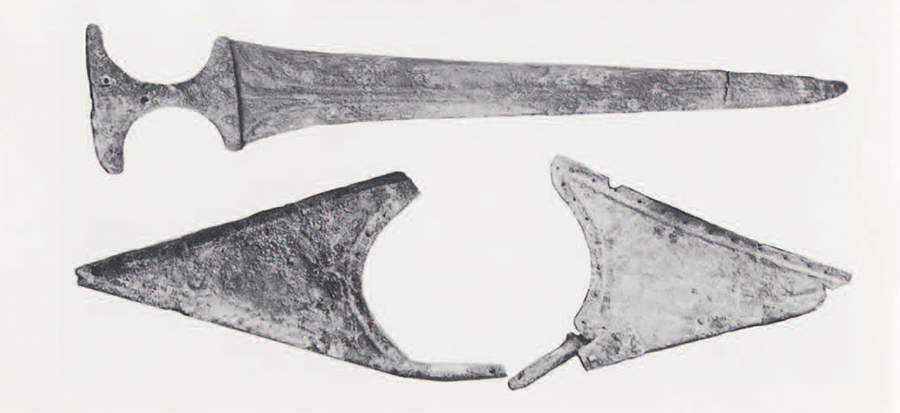

Like many cities of the early first millennium B.C. in northwestern Iran, Hasanlu was suddenly attacked and burned. During the attack and looting many objects were dropped or left in the flaming buildings. Among these were many bronze daggers and the handsome sword shown below. With it is shown what appears to be a piece of shoulder armor with a hole for the neck and perforations along the edges for the attachment of leather or heavy cloth. Such cloth may have been covered with small bronze buttons, many of which have been found loose in the soil. Wide belts with copper plaques were also worn. Warriors carried daggers, spears, and maceheads made of bronze or iron or both.

The plundering activities of Assyrian times are known from many stone reliefs (left) and texts of the period. Objects taken ran into the thousands and were of many kinds. In 714 B.C. Sargon lists among his spoils at Musasir (west of Hasanlu) weapons of bronze, gold, and silver; ivory staffs; bronze shields; silver basins, vases, and braziers; perfume burners; ivory furniture and gold door fittings. Scenes of Iran at Khorsabad (cover) and on the palace of Nineveh (left) suggest the violence of these attacks. When the smoke cleared away from the vanquished city it usually lay, a sprawling burned-out ruin, its walls pulled down, its dead entombed within its fallen palaces (as below) or hanging decapitated from nearby posts, abandoned like the town to the wind and rain. Some such scene caused by Assyrian or Urartian, filled the Iranian sundown the day that ninth century Hasanlu died.