The Egyptian collection of the University Museum came into being during the last decade of the 1800’s. It was then that Dr. William Pepper, Provost of the University, backed by Dr. Charles C. Harrison, Chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, had “conceived the idea of drawing wealthy and prominent Philadelphians who were interested in archaeology but not particularly in the University into an association which would tie them and the institution together. This he did through the formation in 1889 of the University Archaeological Association—the beginning of the University Museum” Percy C. Madeira, Jr., Men in Search of Man).

Prior to that time there had been sporadic gifts of Egyptian objects made to the University, but the creation of the Archaeological Association served as the nucleus of a definite interest in Philadelphia in Egyptology.

In 1890, an Egyptian and Mediterranean Section of the Museum was formed, and naturally Sara Yorke Stevenson became the first curator, a post which she held for fifteen years. Her tenure was a time during which the general direction of policy was set, rules and regulations to which the Egyptian Section specifically and the Museum in general still adhere. In a letter written just before the turn of the century she stated her feelings, shared by her colleagues, that the collection should be available not only to scholars “as a basis for original and comparative study, but also to public school teachers and pupils, as well as the people at large who can enjoy at home some of the benefits derived from foreign travel and a visit to the great state museums of Europe.”

It was a collection which had already, by the later part of the century, outgrown its temporary space in College Hall. When the ‘new’ University Library, in 1890, granted its permission to use one of the rooms therein, the objects quickly took over the available space, and it was clear that something more accommodating had to be provided.

In 1892, Mrs. Stevenson had been elected a member of the Board of the Department of Archaeology and Paleontology. With that honor added to her list of credentials, she campaigned hard for the new museum to be called the “Free Museum of Science and Art”—a name still visible on the front of the present building. A site was selected, plans were drawn up, and pledges were solicited. There were some temporary discouragement with the fund drive which Mrs. Stevenson had to put aright. She even handled the more mundane problems as well, as indicated by her own description of the building site in 1895: “… as the East wind blew—such dense black clouds of smoke swept over the space on which we stood that Mr. Strawbridge and I I. , . begged Dr. Pepper to pause and consider … We therefore notified the architects to devise some plan by which the work could be started on the other end of the lot.” Mrs. Stevenson was describing the ‘pollution’ emanating from the steam-operated trains. Considering our proximity to the tracks, Mrs. Stevenson’s fears were well founded: we are fortunate that trains are now electrically powered.

Eventually, these setbacks proved to be only minor. The problems with money, however, were major, and it was not until the state legislature voted a grant of $150,000 (to be matched) that the building could be begun. The archives contain much material that documents the difficult and time-consuming work done by the backers of the project, of whom Mrs. Stevenson was one, that finally secured the private and public funding necessary for the edifice. Estimates by their very nature being low, the first section alone cost about three-quarters of the original amount named for the whole building. Soon other sections were added, the latest addition, which contains the academic wing, housing offices, teaching departments and laboratories, dedicated in 1971. While the extremely ambitious original design was never completed, the “Free Museum of Science and Art” which, within a few years after its opening was being referred to as the University Museum—a name that would become official in 1913—has provided a good home for the artifacts about which Mrs. Stevenson and her cohorts were so concerned.

Dedicated on December 20, 1899 the first section of the Museum was a landmark in the city. Not only was it a showcase of the creativity of mankind, it was and still is the home of the most comprehensive collection of its kind in the state. The New York Times stated:

“Ten years of energetic effort, liberal support and scientific exploration end today in the opening of the University’s Free Museum of Science and Art … Stored as they have been hitherto . . the Museum has made no such impression on the general public as its character, size and importance deserved.”

The importance of the Egyptian collection was, and still is, that, unlike those of some other institutions which were for the most part acquired through purchase, it is almost entirely excavated. While the early participation of the museum in Egypt was in actuality ‘second hand’ in that the Museum helped to support excavations such as those carried out by the British archaeologist Sir William Flinders Petrie, rather than to organize its own expeditions, some of our earliest association with Egypt was through Mrs. Stevenson, its first Egyptian curator. In 1898 she proceeded to that country as a representative of the American Exploration Society and the city of Philadelphia. Her trip—discussed earlier in this journal (pp. 5, 6)—had many positive effects for this institution, one of which was that the first curator of the section returned with 42 boxes (according to press coverage of her arrival in Philadelphia) of Egyptian material which had been excavated by her agent at Dendereh.

An urgent task was to catalogue these artifacts together with the occasional gifts from local people as well as the fruits of the association with Petrie and the Egypt Exploration Fund. One of Petrie’s pieces from Ballas serves as this museum’s first published object from Egypt, and while we can appreciate the accompanying cogent description of the material, we cannot help but wonder at the proofreaders who allowed the illustration to appear upside-down!

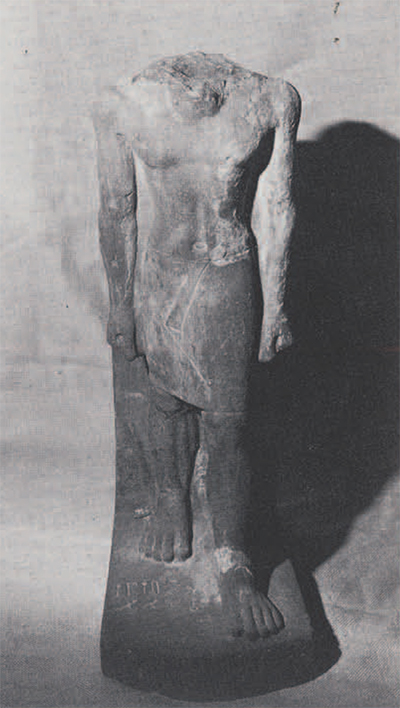

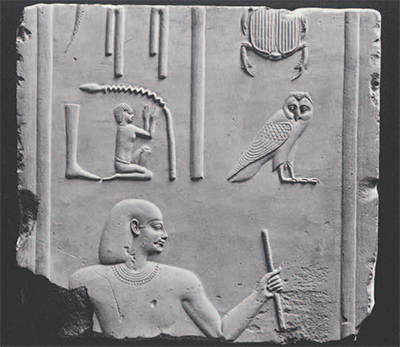

Early scientific excavation set the example for the Museum, and whenever the institution worked in Egypt, directly or indirectly, by our own labors or financial support, the return came in the form of antiquities allotted to us by the Egyptian government. The long-standing interest in Egypt, coupled with the diversity of sites chosen, makes the collection quite representative of the long-lived culture of the ancient Egyptians. Town sites, temple sites, palaces, cemeteries, pyramid sites, and provincial areas, all were part of the itinerary. From the royal and provincial workshops come superb reliefs and statuary, architectural elements, and so forth. Tools, implements, jewelry, medical instruments, textiles, written material, and pottery and stone vessels and even human remains comprise the collection which, according to records just before the turn of the century, ranked only third in popularity after the Babylonian and the American Indian Halls. Needless to say, the attendants’ salaries reflected this difference: $4.00 per week in the Babylonian Hall versus $3.00 per week in the Egyptian Hall. While not one of the best known collections of Egyptian material, the University Museum’s collection is one of the most significant because of the completeness of the scientific record. If the context of an object is known, then the dating and analysis can be easier and more precise. Purchased pieces often owe their stated provenience, date, and authenticity to stylistic comparisons with pieces from recorded sites. Therefore, some of our objects, although of a less aesthetically appealing nature to our modern eye than some beautifully executed object purchased on the art market, often provide the basis for our knowledge of the latter.

While outright purchases were limited, the Museum did acquire a substantial portion of its papyrus collection through purchase. Max Muller, acting on behalf of the Museum shortly after the turn of the century, compiled an impressive array of papyri from the local dealers in Egypt. Combined with material acquired through the Egyptian Exploration Fund and later University Museum excavations, the papyri collection contains documents from Pharaonic through Graeco-Roman Egypt. An article in a previous issue of Expedition (Winter, 1978) provides detailed information regarding written material in the Museum.

Benefactors too have played a substantial role in helping to determine the nature of the collection by their choice of which Museum project to support financially or to which objects offered for purchase to contribute.

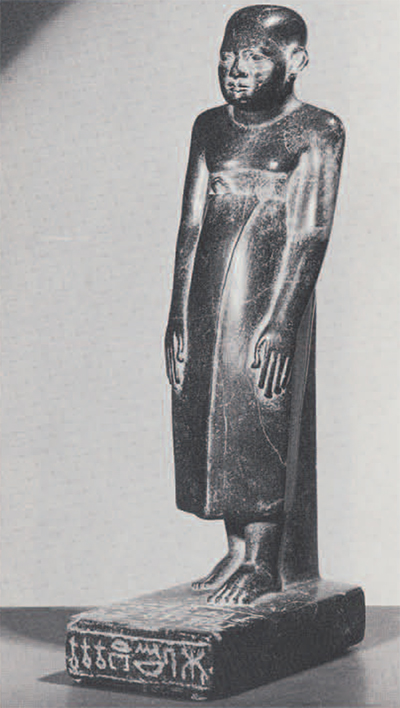

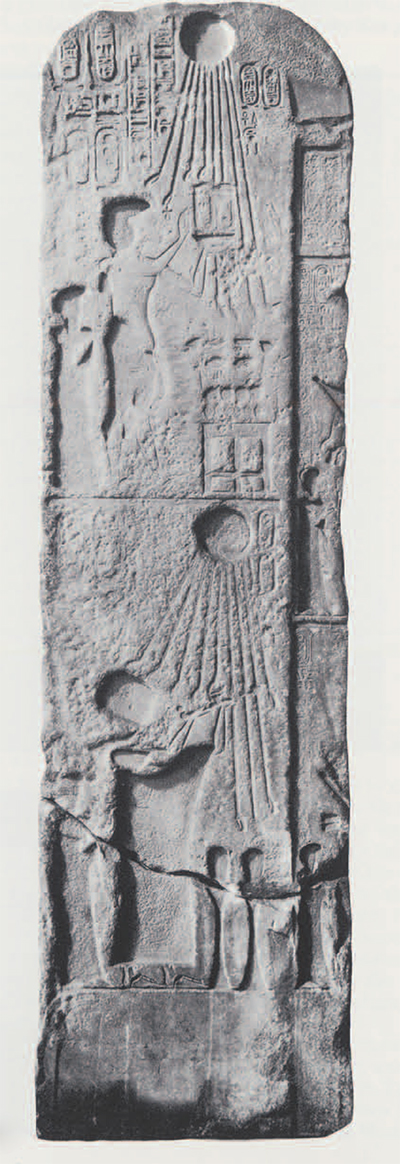

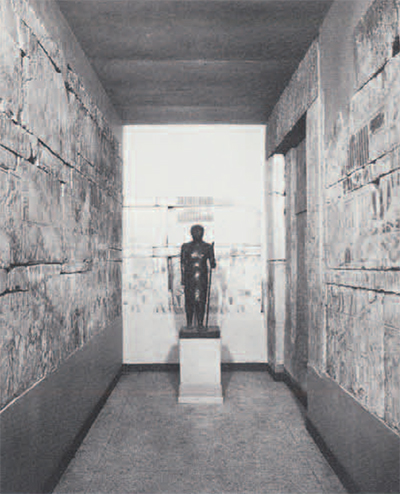

Notable among these early benefactors were Eckley B. Coxe, Jr., John Wanamaker, Dillwyn Parrish, Mrs. John Harrison and Charles C. Harrison. Mrs. Stevenson gave not only of her time but also of her own personal collection of artifacts. In 1904, Mr. Wanamaker purchased the tomb of Kapure, the major section of an Old Kingdom mastaba from Saqqara, which is on display in the lower Egyptian Gallery. He also secured for the Museum a large, red granite sarcophagus and other items of importance which also had been exhibited at the St. Louis World’s Fair. Through Dr. Muller, Mr. John F. Lewis donated much of his Egyptian collection which contained one of the finest Books of the Dead on exhibit in this country. Temporary loans of objects had the habit of becoming permanent, such as the important stela of Akhenaton that came here in 1900 on loan. Thirty-one years later, it became a permanent addition to the collection. The early records show prominently the name Lehman as the source of many fine items originally on loan which later were made permanent acquisitions. If an outside collection came to the attention of those in charge, funds for the purchase were raised by the Board. The majority of the objects in the collection, however, were a product of the Museum’s work in Egypt, and of those acquired in other ways, many were fully documented. Because of the time spanned (almost a hundred years), the method of operation (either its own expedition or by support of an outside expedition) and the variety of field directors, the range of the collection is extremely broad.

The name of Eckley B. Coxe, Jr. turns up often in regard to the Egyptian Section of the Museum, since in addition to the generous and virtually unrestricted support he gave to the Egyptian fieldwork, he arranged for his aid to continue beyond his own lifetime. Through the terms of his will, an endowment was established for the maintenance of the Egyptian Section. The income from this fund has been a valuable asset, representing one of the primary reasons for the success and continuity of Egyptology at Pennsylvania.

Unlike many other museums, where the curator of a section will often base his acquisition policy upon the gaps in the present collection, the University Museum often did not have a resident curator of its Egyptian Section. Although it periodically employed members with curatorial rank, their function in the Museum was minimal, while their function in the field was paramount. Not until Mr. Battiscombe Gunn joined the staff in 1931 has there been a curator interested primarily in the collection. The commitment to the field was made early and was consistent, but the commitment to the collection in terms of display, conservation and publication was not always so carefully directed.

Mrs. Stevenson resigned in 1905 and David Randall MacIver became curator in 1907. His duties, however, were as field director in Egypt. A well known German Egyptologist, Hermann Ranke, came to teach Egyptian for three years until 1905, but he had no curatorial position. W. Max Miller had University affiliation in 1909-10 but no official museum position, despite the fact that his interest and work were in large part responsible for our papyrus collection. In 1920, Henry F. Lutz was a Research Instructor in both Assyrioilogy and Egyptology. Nathaniel Reich, later Professor at Dropsie College, was an assistant from 1922 to 1924, translating some of the Egyptian papyri. During this time Professor George Barton, whose major area was in Semitics and Biblical Studies, occasionally taught Egyptology for the University. It is clear that the Museum was not at a loss for Egyptological talent during these early years. It is odd, however, that full, consistent and continuous advantage of these talents was not taken.

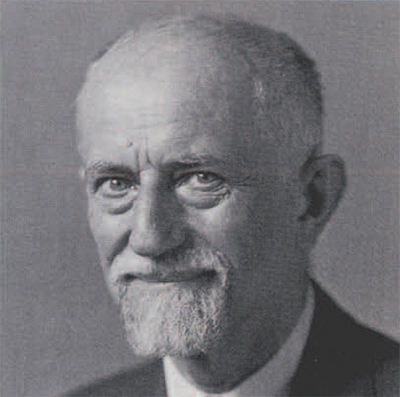

For eleven years (1914-25), Clarence Fisher as curator directed the expeditions in Egypt, while at home little was done with the collection or teaching program. He did, however, have responsibilities with the collection and when at home concerned himself with them. Shortly before leaving the Museum, in a letter to Gordon, dated April 15, 1924, he discussed the installation of Egyptian objects in the new wing and the need for a comprehensive card catalogue. He also mentioned plans for a handbook “giving not a detailed cata-logue of the objects, but written as a connected story of the rise and development of Egyptian art and merely using the exhibits to illustrate it.” Although exhibiting foresight, his suggestions did not meet with immediate acceptance.

The collections were installed in time for the opening of the Coxe Wing in May 1926, but it was not until 1929 that his idea of a comprehensive card catalogue came into fruition. When Horace H. F. Jayne was appointed Director of the Museum in May of that year, one of his first projects was to establish a card catalogue for the entire museum. A registrar was appointed and a number of temporary assistants were engaged, some to copy onto cards the data on catalogued objects written in the large accession books, others to catalogue previously uncatalogued material. The work in the Egyptian Section was begun with the thousands of objects excavated by Fisher between 1914 and 1925 and identified only by their field accession numbers. Dorothy Cross and Margaret Moon had the job of finding each of these objects, giving it a Museum catalogue number and making the catalogue card, using the information in the field catalogue. As to Fisher’s idea of a published catalogue, it was not until more than twenty-five years later that Hermann Ranke published a catalogue of the collection, and now, fifty-five years later, the Museum is mounting an exhibition of ancient Egyptian material where the objects displayed are virtually the illustrations for the story being told. Fisher was succeeded as field director by Alan Rowe, who spent almost all of his time in Egypt (see page 26).

In 1931, Battiscombe Gunn came to Philadelphia as Curator of the Egyptian Section and, according to his obituary, it was here that he made a “new discovery—the secret of successful teaching.” He did some teaching in the Museum but was never appointed to a teaching position in the University. A superb British philologist who had already published a substantial volume on Egyptian grammar, Gunn had previously been Assistant Keeper of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Although he spent only slightly more than three years here, he made a consistent effort to complete the cataloguing of the collection, to organize all the holdings in a consistent manner, and to number all objects. Material that had been donated as a group was now individually catalogued and numbered. As a philologist, his attention was directed 5 also toward the large collection of papyri only incompletely organized by Muller and Reich. Through Gunn’s efforts in conservation, mounting, and identifying the papyri, the scope of the collection was realized. In a short time, Gunn had made the first concerted and sustained attempt to organize the entire collection, and his thoroughness included examination of the collection of amulets and the organization of them by types of stone. To help the researcher unfamiliar with lapidary nomenclature, he included a helpful list of terms with descriptions, such as: “chrysoberyl is not a variety of beryl”; and “carnelian is red chalcedony.” When faced with questions regarding the material we received from our support of the Sedment expedition, Gunn wrote directly to the excavator, Guy Brunton, for the particulars. Gunn did not however, take an active interest in the field during the period that he held the title of Curator of the Egyptian Section. He was assisted in his work by Phillips Miller and Margaret Moon.

A third assistant, Carroll Young, began work shortly before Gunn left Philadelphia to accept the chair of Egyptology at Oxford. She provided the expertise in the Section until a new curator, Hermann Ranke, was appointed in 1938. Ranke, who had been teaching at the University severe decades before, was the first Egyptologist at the University who had official teaching and curatorial responsibilities, and, with his dual appointment, Egyptology at the University was beginning to be treated on a strictly professional level. While attempts by Ranke were being made to publish previously excavated material, little concrete results for this venture were forthcoming during his tenure. Egyptological activity was limited to Philadelphia now until the early ’50’s, when the Museum would again sponsor an expedition to Egypt.

Ranke, however, published several articles on museum objects and produced the guide to the Egyptian exhibition published as volume 15, nos. 2-3 of the 1950 University Museum Bulletin. It was not a handbook as Fisher had visualized but a traditional guide to the Museum’s collection with prefatory essays on chronology, geography, history, and religion; there is no essay on art. Now out of print, it is to this day the only published record of the Egyptian exhibition. Ranke could accomplish only part of his ambitious goals, since his dual appointment made it necessary for him to maintain an Egyptologist teaching program in addition to his curatorial responsibilities. He directed as much of his attention to the galleries and storage areas as possible: he rearranged the exhibition of mummies and took a strong interest in conservation. He frequently queried John Cooney, the Curator of the Brooklyn Museum, regarding problems of conservation, and Mr. Cooney reciprocated by studying advanced stages of Egyptian philology with Dr. Ranke. Ranke’s organ-ization is indicated by one of the monthly Section reports that he prepared:

MONTHLY REPORT ON WORK DONE IN THE EGYPTIAN SECTION

1. Mending of pottery continued.

2. Cataloguing of pottery and negatives continued.

3. Rearrangement of exhibition of alabaster vases and recataloguing of same.

4. Preparatory work for rearrangement of pottery for exhibition, according to periods.

5. Study and recataloguing of scarabs continues.

6. Copying and studying of inscriptions on Sailic statue.

7. Cleaning of Old Kingdom lintels and New Kingdom stela. B. Rearrangement of some objects in Upper Hall.

It is clear that bath Ranks and his predecessor, Gunn, were primarily interested in and devoted their time to the collection. It was the intent of Gunn, who was then followed by Ranke and his assistants, to locate, identify, and record the more than 40,000 objects that then comprised the collection. Ranke was fortunate to have Carroll Young assisting him, and it was she who “held the reins” during the seven years that elapsed, until Ranke returned in 1949 as Visiting Curator For two more years. Miss Young continued the practice of monthly Section reports, documenting her activities. Kenneth D. Matthews [later director of the Educational Department) and Barbara Copp, among others, assisted her in her efforts. The tatter aide, now Barbara Wilson, is still part of the Museum, devoting her valuable time to the maintenance of the Archives, and with-out her help and advice, articles like this one could never be written.

On November 18, 1943, Miss Young stated: “I continue to try to track down missing numbers on the field negatives and to track objects that have lost their numbers back to their original cards, I believe it to be worthwhile and what Professor Gunn had started and wished us to finish.” Her perseverance in regard to the collection took her into all aspects of the work, and her reports documented the variety of her activities: new acquisitions cataloguing the Egyptian objects of Mr. Madeira’s gift” (December 18, 1942); field notes—”Mr. Brickelmajer is now helping me find numberless objects pictured on the negatives. We spend Saturday mornings in the cellar looking for these objects, so that we may type their numbers on the negative bags” [February 17, 1944); storage collection—”The Theban material (we have all of it here) would also make a fascinating volume. We have catalogued 300 Theban field negatives this month and the more I work with them, the more I realize what a shame it is that we can not get an Egyptian Archaeologist like Dr. Ranke to publish them. There are so many human touches in the inscriptions. One broken fragment reads: `. . , which I have passed upon earth as one happy with my wife and all my children …’ A third gentleman is so gallant he even includes his mother-in-law’s name on his tomb wall” (December 21, 1944). Miss Young often dealt with the public, as her records indi-cate: “Mr. Rose … was back again, this time for information on a galabieh.’ I gave him sketches of this Arabic cloak, but Mrs. Henry (Grace Henry, in the Educational Department) gave him the most help . Took three friends of Miss Kraus through the Egyptian Section” (January 18, 1945). “A Mr. Keely from Roxborough also brought in a forged limestone stela which I translated for him and explained my reasons for believing it a forgery. Goodness knows why he was pleased to know he had a forgery, but he was, for he sent me some music he had written as a thanks offering” (April 18, 1945). Miss Young frequently guided tours of school children and other interested parties through the Egyptian collection, and it was she who fielded inquiries from a variety of scholars: “Dr. Stanley Truman Brooks is interested in finding Ramie in Egyptian textiles. So I have sneezed through 124 fragments of linen …” (February 28, 1946). Her interest in the conservation of the collection is well indicated in her Section report of April 18, 1946: “The Dow Flake la dehydrating agent] is melting again and will soon need to be emptied a second time. In this connection, I would like to say that there is really a crying need for a trained chemist in the Museum to treat diseased specimens.”

Her dedication to the collection in all its manifestations can be appreciated in her monthly report for June 1946: “I thoroughly cleaned the Upper and Lower Egyptian Sections, scrubbing dirty woodwork and fingerprints off the outside of Kaipure’s tomb and the pyramid model. Also washed all the stone sarcophagi that could not be harmed by soap and water, i.e. such stones as marble and alabaster; straightened crooked objects in their cases; typed, cut and mounted new labels when they were dirty or even torn and covered all the labels in both halls with clear acetate; made new acetate covers for the offering trays . . .”

While Miss Young’s hopes for a noted Egyptian archaeologist to take over as Curator were fulfilled when Dr. Ranke returned to Philadelphia in 1948; he stayed only two years. In 1950, another noted German Egyptologist, Rudolf Anthes, came to the University Museum as curator. Like his predecessor, he too had a University appointment as Professor. Unlike Ranke, however, he also directed fiield-work in Egypt. Anthes, then, became the first Egyptologist at the University Museum to have an official tripartite appointment, a precedent that would continue with his successors as well. It took more than half a century, but the Egyptian collection of the University Museum was finally receiving professional care on a consistent and continuous basis—the kind of attention its former caretakers had tried to establish. It is not surprising then, that it is about this time that there appears to be a flurry of outside interest in the University Museum’s collection. Among the many congratulatory letters sent to Anthes by Egyptological scholars around the world, there are none which do not comment on the quality of Anthes’ new collection, Professor Edgerton of the Oriental Institute in offering Anthes the hospitality of Chicago stated: “We hope very much that you will soon give us the pleasure of seeing you here in Chicago. We cannot show you a museum comparable to Philadelphia or Boston—but you will find a few antiquities of some slight interest .. .” Almost all of the Egyptologists who wrote added their regrets at not having seen the collection in Philadelphia, and each indicated his intention of visiting soon. The following letter of Cyril Aldred of October 1950 to Anthes at his accession is typical of many letters the new Curator/ Professor received: “I regret that I do not know the Philadelphia Collections at all well—though I believe they contain material worthy of your expert attention.”

It was probably Ranke’s catalogue more than anything else that was responsible for bringing the collection to the attention of the Egyptotogical world. Anthes was constantly being requested to send information regarding particular pieces pictured or mentioned in the catalogue. His own catholic interests caused his answers often to include questions regarding either objects in other collections or opinions on a particular matter. His correspondence grew, therefore, as did his reputation for aiding all scholars in regard to the Egyptian collection, whether neophyte or established. His assistant, Henry Fischer, aided in handling the correspondence, organizing the storage material, and handling curatorial problems. When Anthes went to the field in 1955 and 1956, Fischer accompanied him. Later Alan Schulman assisted in the Section.

Public attention to the Museum in general, and to some extent the Egyptian collection, grew when in 1951, the University Museum launched its critically acclaimed and award-winning television program “What in the World?” Dr. Froelich Rainey, then Director of the Museum, acted as moderator to a panel of experts who would try to identify on the air an unknown object from the collection. John Cooney and Bernard Bothmer of the Brooklyn Museum were frequently guest panelists.

Anthems covered the three aspects of his position admirably. Not only did he take care of the collection and teach, he also managed to provide preliminary reports on his excavations almost immediately after his season and a finished text shortly there after. The Dendereh material from the early Rosher and the later Petrie excavation was brought in to order following early organization by Miss Young, and it formed the basis of Henry Fischer’s dissertation. The archaeological material from the site was later used for the thesis of Ray Slater. These studies provided the direction for publishing the vast quantity of archaeological material that comprises the collection.

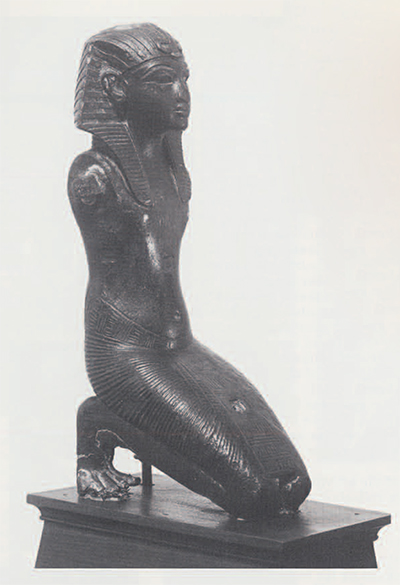

Anthes was interested in making available to all scholars the resources of this institution. Through him, Bernard Bothmer, first at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and later at the Brooklyn Museum, compiled a wealth of information regarding the pieces in Philadelphia. This knowledge served him well, for many objects in his corpus of Late Egyptian Sculpture are from the University Museum. We supplied him with several of these works of art for Brooklyn’s exhibition “Sculpture in the Late Period”; in 1973 Bothmer borrowed from our Amarna collection for his Museum’s exhibition, “Akhenaten and Nefertiti,” and in 1978, a substantial portion of the Brooklyn Museum’s exhibition, “Africa in Antiquity,” is from the Nubian collection of the University Museum.

In 1953 Dr. Elise Baumgartel wrote to Anthes regarding the nature of the pre-historic material:

You may remember my visit to your Museum in 1950, and how impressed I was by the amount of material it possesses from Flinders Petrie’s excavations at Naqada … I am just preparing for the printer the second revised edition of my Cultures of Prehistoric Egypt , . I intend to attach to this second part a catalogue of the contents of the Naqada graves, hut I can hardly do that without the material in your keeping . . . You must have more than a thousand pieces … The Naqada material is still the most important ever excavated from Pre-dynastic Egypt and is still vastly un-known. Petrie published about 50 graves (incomplete out of about 3000 … (October 21, 1953)

A similar story can be found for almost every scholar after he had seen the collection for the first time, and Anthes tried to make as many people familiar with it as possible.

One of the activities that made the Egyptian collection more prominent did not, however, have much to do with Dr. Anthes. Late in the 1950’s, the world had begun to become concerned over the certain destruction of the Nubian monuments to be flooded by the construction of the new Aswan Dam. The University Museum, along with other concerned organizations, mounted expeditions in conjunction with Egypt to save these treasures. To bring attention to this work, including a group of 34 objects from the tomb of Tutankhamun’s lent by the Egyptian government, an American exhibition of Egyptian antiquities was planned. Dr. Rainey, with the help of David Crownover, Museum Secretary, organized this exhibition which opened in the National Gallery of Art in October of 1961 and came next to the University Museum in December. A total of 16 institutions hosted the show, and 73,000 people saw it here for its one-month stay. Needless to say, the Egyptian Section became even more popular. The exhibition was entitled “Tutankhamun’s Treasures.”

By the end of 1962, Dr. Anthes had retired, but it was not until 1964 that the Museum found a replacement, Dr. David O’Connor, an Australian Egyptologist trained at University College, London and Cambridge. Having worked with one of B9 Britain’s most renowned Egyptian archae-ologists, Brian Emery, Dr. O’Connor’s appointment indicated the University Museum’s commitment to working in Egypt at the highest professional level. Like Anthes, O’Connor had duties of tripartite nature. Along with teaching archaeology and history in the Department of Oriental Studies, he has maintained ongoing expeditions in Malkata and Abydos. In addition, he organized in 1971, an exhibition regarding the University Museum’s work in Abydos and was responsible for the reinstallation of the Mummy Room in 1970. Under his curatorial direction, the room depicting the activities of daily life in Ancient Egypt was redesigned and implemented.

Dr. Jaroslav Cerny, who held the chair of Egyptology at Oxford University, was visiting professor during the Fall terms of 1965 through 1968: he taught all phases of the Egyptian language. Dr. Ahmed Fakhry and Dr. William Kelly Simpson were visiting curators for a short time.

After Cerný’s return to England, Lanny Bell assisted O’Connor in the Egyptian Section, eventually becoming Assistant Professor of Egyptology in 1976. Dr. Bell, too, had responsibilities in Egypt and his epigraphic and archaeological expeditions to Dra abu el Naga continued the University Museum’s earlier commitment to the site under Clarence Fisher. Throughout his tenure at the Museum, Bell also assisted O’Connor in all curatorial matters. Dr. James Weinstein and Dr. Ray Slater assisted in the section, working on the research and conservation of stone, pottery, and metal.

Both O’Connor and Bell were well supported by a man whose dedication to the Section cannot be matched, Charles Detweiler, who has voluntarily cared for the storage section for more than a decade, still keeps his protective watch over it.

When Lennie Bell accepted the position of Director of Chicago House in Luxor, Egypt, in 1977, Dr. David Silverman came to Philadelphia from the Oriental Institute and Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago for a one-year appointment. In July 1978 he was officially appointed Assistant Curator of the Egyptian Section and Assistant Professor of Egyptology for the Department of Oriental Studies.

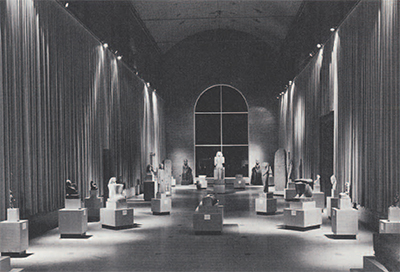

“The Search for Ancient Egypt,” an exhibition of objects detailing the University’s Museum’s work in Egypt for almost 100 years, is the first major project of the present Egyptian Section of O’Connor and Silverman. Opening early in 1979 and consisting of more than 200 pieces, most of which have never been displayed, the exhibition again testifies to the importance and level of quality of the Egyptian collection at the University Museum.