It is a common anthropological fallacy to think that people who forage for their subsistence are living remnants of simpler ways of life, resembling how our ancestors once lived. Even people who rely mostly on wild foods and make most of their own tools are well aware of many aspects of the modern world. Humans have always interacted with each other, borrowed useful new tools or practices, and maintained keen awareness of the changing natural and social world. This point was brought home to me during my first fieldwork with the Pumé Indians of Venezuela. In the initial month among them, I occasionally made “cowboy coffee” by throwing coffee grounds directly into hot water. The Pumé, having observed how the local Venezuelan ranchers (criollos) make coffee, were appalled. One morning, the oldest woman in camp marched over and showed me how to make drip coffee using a filter she made from a pair of my old shorts. Although the Pumé never made coffee during the first 24 months I lived with them, they knew how to do so. This illustrated one of the most rewarding aspects of ethnographic research—the delightful surprise when a simple gift, such as a coffee filter, expanded my scientific perspective of anthropological questions.

Ethnoarchaeology

In the early 1990s I took my interests in how foraging peoples use their technology to Venezuela and began an ethnoarchaeological study of material culture and behavior with the Pumé Indians. In the last 30 years ethnoarchaeology has become an important component of archaeological research. Ethnoarchaeology is ethnographic research among modern people that emphasizes observations about their technology to improve our understanding of artifacts found in archaeological sites. By observing the living adaptations, technology, social organization, and subsistence practices of traditional peoples, ethnoarchaeology provides clues about how to investigate ancient behaviors from the material remains of past cultures.

To do this, some ethnoarchaeologists try to find modern examples of traditional peoples that most closely resemble the archaeological cultures they study. This sometimes means studying their modern-day descendents. For example, archaeologists in the American Southwest often rely on behavioral reconstructions based on analogies with living Pueblo peoples to interpret the archaeological remains of their ancestors who inhabited the same area and used similar architecture and gardening practices.

However, such direct connections between modern peoples and ancient cultures, often is impossible. Today’s foraging societies exist only in certain environments and do not represent the full range of past practices found in the great time depth and geographic extent of the archaeological record. Ethnoarchaeology is not limited by these differences. We can study modern people who share particular activities in common with archaeological subjects, such as comparable subsistence practices, technologies, or natural environments. Creative opportunities to learn can even come from events with no direct archaeological analog. The Pumé coffee filter taught me a lesson pertinent to questions about past trade, cultural interaction, and innovation.

The analytic utility of ethnoarchaeology is powerful if we broaden our studies to include many different modern cultures. For example, productive ethnoarchaeology can address specific behaviors of archaeological interest, such as bow and arrow hunting or root collection, independently from modern adaptations, such as the use of clothing and metal tools. This does not mean that we ignore modern behaviors. Ethnoarchaeology also tries to understand why some aspects of traditional subsistence and technology persist into the 21st century and why others change.

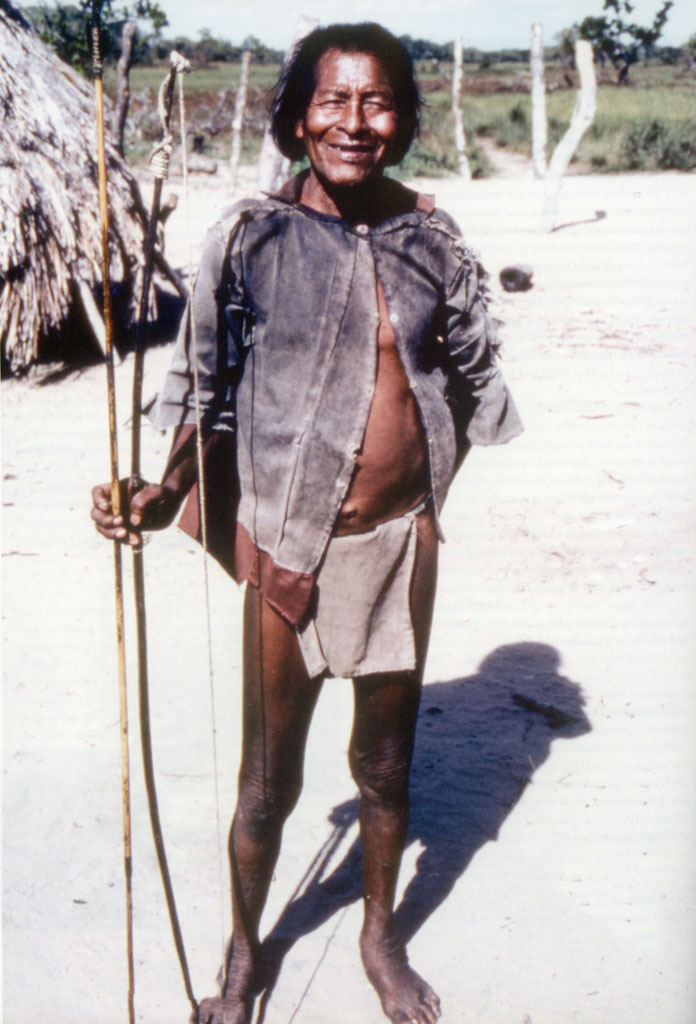

Pumé Foragers Of Venezuela

Vincenzo Petrullo undertook the first ethnographic description of the Pumé Indians in 1933–34 while working for the Penn Museum to establish research relationships in Venezuela.

The Pumé are a group of foraging and horticultural people who live in the savannas of southwestern Venezuela and follow two general patterns of subsistence and settlement. Communities living close to major rivers are generally larger, and some are more acculturated to the wider Venezuelan society. Although they still practice some hunting and wild plant collection, they are primarily reliant on the fish, manioc, plantains, and market foods they purchase with wages earned by working for local Venezuelan cattle ranchers. These “River Pumé” live in mostly permanent villages, although they sometimes occupy temporary fishing camps during the dry season.

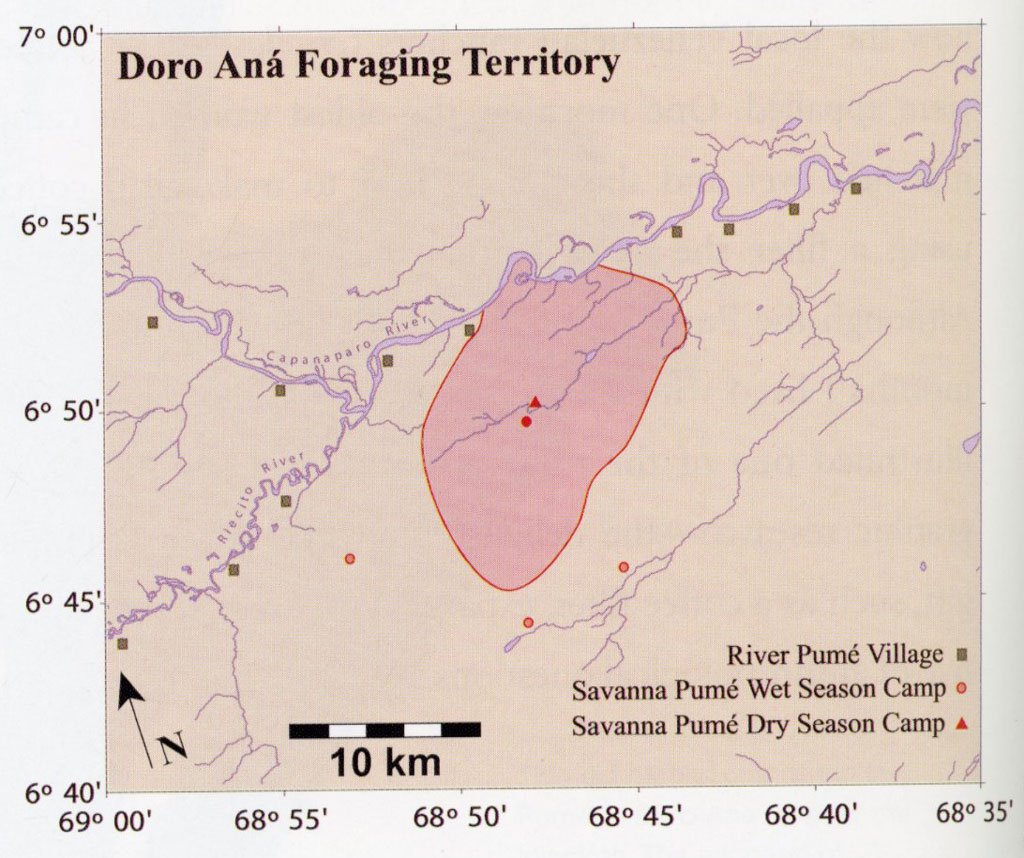

In contrast, the “Savanna Pumé” live in the more open grasslands between the Capanaparo and Cinaruco Rivers and rely more on foraging for wild game, fish, wild roots, and mangos for most of their subsistence. The Savanna Pumé are quite mobile and move camps extensively throughout the year. In 2005, we documented six different main base camps that were occupied during the previous 12-month period.

The savannas, or llanos, where the Pumé live are vast flat grasslands broken only by sand dunes, stands of moriche palms, and low forests along the major water drainages. These savannas are subject to extreme climatic variation, evenly divided between six months of dry season and six months of wet season when 80% of the rainfall occurs. This seasonal change has dramatic effects on vegetation, water levels, and the distribution of fish and animals.

In the wet season, fish are dispersed throughout shallow waters covering the llanos. While they can still be caught in the main rivers, the Savanna Pumé cannot effectively fish at this time of year because the fish are too widely distributed across the landscape. Instead, men hunt primarily armadillos and tegu lizards during the rainy season, and occasionally get larger game, such as deer, anteaters, capybara, or caimans. During this time, women collect significant quantities of wild roots and both men and women engage in garden work to produce relatively small harvests of manioc—a starchy root familiar in the U.S. primarily as the source of tapioca flour.

During the dry season, fishing can be highly productive since fish are concentrated in rivers, streams, and isolated pools. Mangos ripen in this season and form an important part of the diet. For the Pumé, this is the time of relative plenty, while the wet season is associated with weight loss and higher susceptibility to disease.

The stark contrasts in this environment and the changing availability of protein-rich foods, plant foods, and water makes this an ideal location to study how humans solve problems of subsistence through their knowledge of ecological variation and technological tactics.

Tool Use Among the Pumé

Most of what archaeologists know about tool use comes from what we can glean from the design of artifacts and the contexts in which they were discarded. In contrast, ethnoarchaeological

observations provide a much richer view of the production requirements and subsistence demands that shaped the patterning of material remains in archaeological sites. In particular, ethnoarchaeology allows us to see how tools are actually used and how technology can be related to other types of archaeological data. For example, a very productive framework for looking at tool use is in relation to peoples’ subsistence behaviors. By studying how modern people use tools to acquire food we can develop models that help us interpret tools in relation to animal bones and plant remains at archaeological sites—the residue of past food acquisition.

Museum Object Number(s): 96-1-1002

My ethnoarchaeological study of Pumé technological behavior had two goals—an understanding of foragers’ subsistence practices and improved methods for archaeological research on technology. I began my research on Pumé subsistence practices by reviewing the ethnographic literature. This was heavily focused on men’s hunting practices—a common bias found in ethnographic reports that tend to emphasize men’s labor over women’s activities.

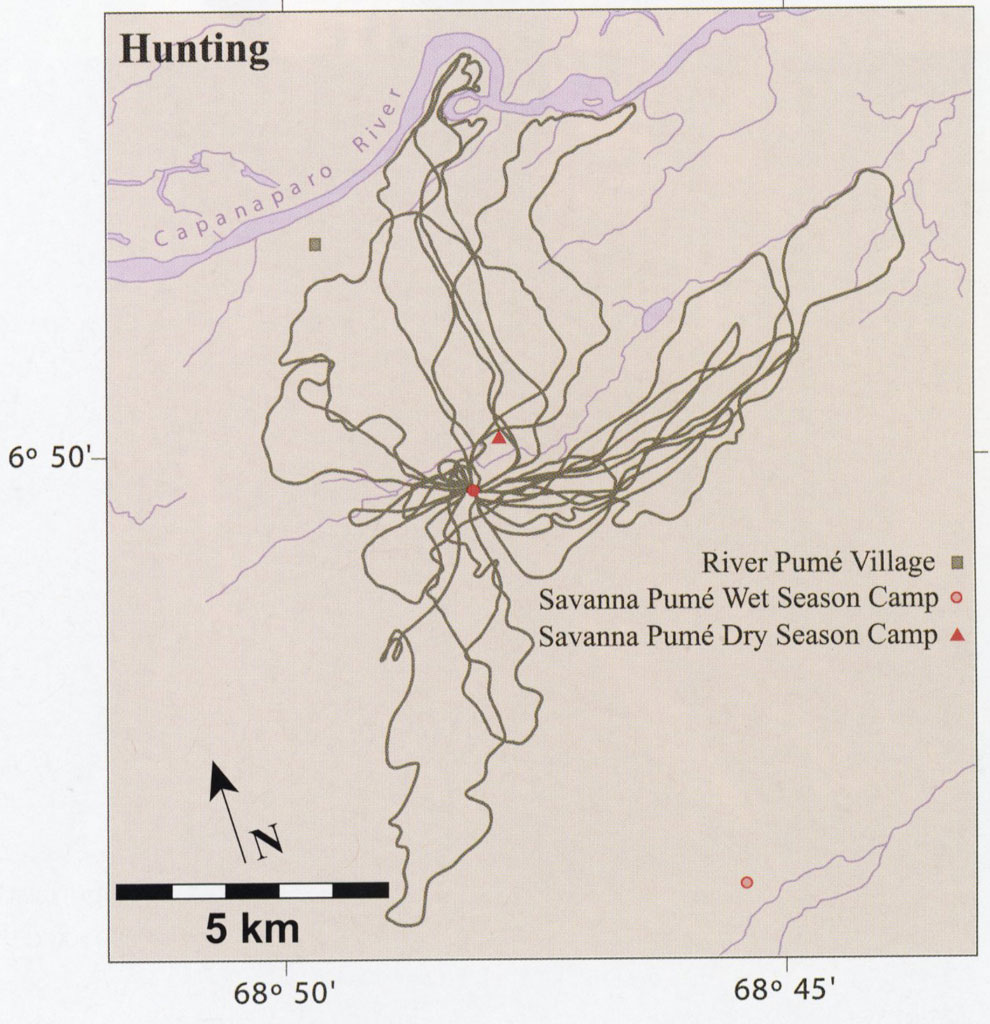

Based on ethnographic accounts about hunting across many foraging societies, I predicted that different kinds of search activities during hunting, fishing, or root collection would determine tool use strategies. To assess this prediction I contrasted foraging trips of various distances. My expectation was that longer trips would encounter more foods and other resources (e.g. raw materials or medicines), and as a result, foragers might take more tools with them on longer trips. More importantly, because there is a limit to what can be carried, I expected the implements used on longer trips would each perform more tasks than on short trips. I made the same predictions for hunting, fishing, and root collecting trips. What I found when I compared these different foraging behaviors was both interesting and often unexpected.

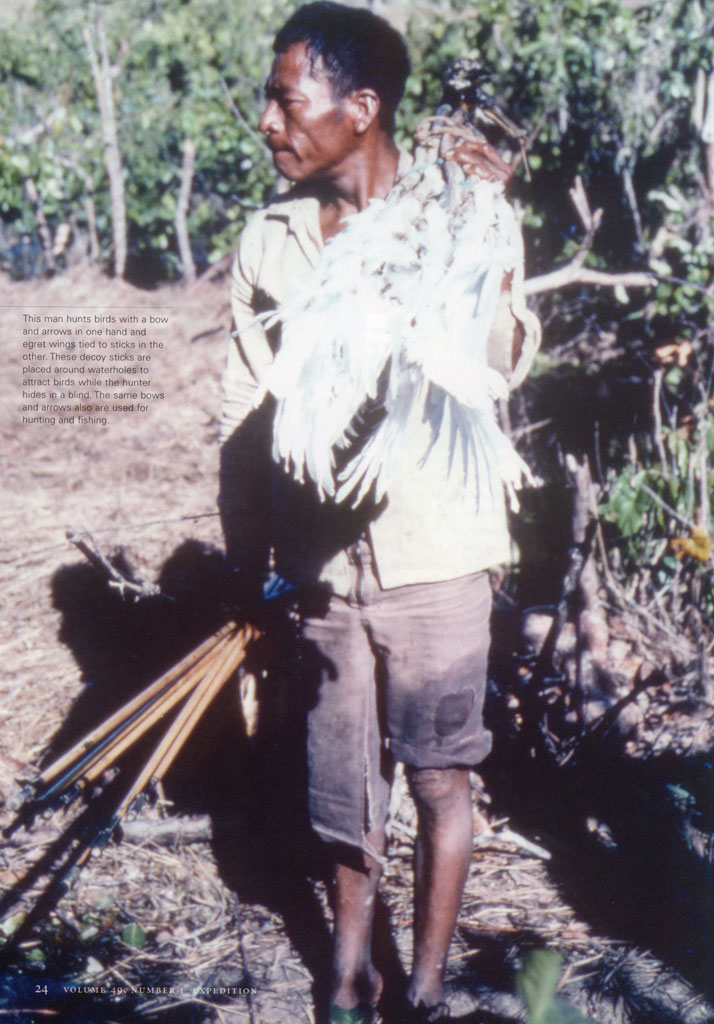

For hunting, the length of men’s trips was strongly correlated to the number of resources encountered. Similarly, the number of functions a tool fulfilled increased with the distance traveled and resources encountered. What was most interesting, however, was how my expectations were not met. During hunting, men did not take more tools on longer trips. Instead, they used their basic kit (bow, arrows, knife, and machete) more flexibly. This was particularly true for bows and arrows. Although designed to shoot game, they are actually used more frequently as field knives, carrying poles, probes, digging sticks, and clubs. Ironically, knives and machetes— designed to be multifunctional—were employed for far fewer uses on hunting trips.

During fishing trips, Pumé men and boys check creeks, pools, and lagoons near their camps to see if rainfall upstream has brought new fish downstream. If they find fish, they stop and fish there. If nothing is biting, they move on to another location until they do find fish, since there is no predictable gain to simply staying at a particular pool. As a result, the distance traveled is not directly correlated with the amount of aquatic resources caught. Longer fishing trips did not encounter more fish than shorter trips. Furthermore, since almost all the resources pursued during fishing are aquatic, there are few differences in how fishing tools are used to catch them. The same tools that are used flexibly in hunting (bows and arrows) perform fewer kinds of tasks during fishing trips. Because of how men search and catch fish, none of my predictions about tool use were borne out during fishing.

What about women’s root-collecting trips? Unlike hunting and fishing, women can monitor the condition of wild roots prior to harvesting them. Women know precisely where to search and have a good idea of the density and quality of root patches and when to exploit them. This produces high yields of roots, and no trips came back without food. In contrast to fishing, even when fewer roots are present than expected, women can stay in a root patch longer and harvest an amount of food proportional to the time they work. As a result, like fishing, the distance traveled to a patch did not correlate with the amount of resources encountered, nor did tool use change during longer trips. Digging sticks and baskets are all that is needed. Again, my foraging expectations were not met.

The deviations from my research expectations are valuable lessons about the search for food, labor differences between hunting, fishing, and root collecting, and how technology serves these strategic behaviors. This is how science works. I used ethnographic literature to develop behavioral models and expectations and tested them against carefully recorded ethnoarchaeological data. This understanding of Pumé foraging can be compared with research on subsistence and technology in other modern groups. Linking my observations of tool use with the kinds of foods the Pumé pursue expands archaeological methods for studying stone tools in relation to detailed research on animal bones and plant remains.

Adding To The Museum’s Collection

As part of my research I acquired a comprehensive collection of Pumé material culture during my long-term ethnoarchaeological study. For each item I recorded detailed information about its use in various activities, and each is related to the observations I made about technology. Most of the items in the collection come from the Savanna Pumé community of Doro Aná where my research has focused. The collection contains multiple examples of most types of implements, showing the variety of tools available and not just the average or “best” example. Many of the tools have been used, and some are almost worn out, showing the effects of the various activities I recorded.

In 1996, I donated this collection of 1,311 artifacts to the Penn Museum. It presently contains material from my 24 months of research in 1990 and 1992–93. In the future I will be adding artifacts from my recent collaborative work with Karen Kramer of Stony Brook University on Pumé subsistence, demography, and health issues.

I am currently engaged in a comparative study of my collection with one collected by Vincenzo Petrullo in 1933 and two others made by Anthony Leeds in 1958 during research on the Pumé. These collections offer exciting views into the changing material culture of one of the few remaining foraging peoples on Earth, and provide clues about how to interpret the archaeological evidence of subsistence strategies.

Leeds, Anthony. “The Yaruro Incipient Tropical Forest Horticulture: Possibilities and Limits.” In The Evolution of Horticultural Systems in Native South America: Causes and Consequences, edited by Johannes Wilbert, pp. 13-46. Antropológica Supplement No 2. Caracas, Venezuela: Editorial Sucre, 1961.

Petrullo, Vincenzo. The Yaruros of the Capanaparo River, Venezuela. Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Anthropological Papers No. 11. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1939.

Wilbert, Johannes, and Karin Simoneau. Folk Literature of the Yaruro Indians. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Latin American Center Publications, 1990.

Yu, Pei-Lin. Hungry Lightning: Notes of a Woman Anthropologist in Venezuela. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1997.

Museum Object Number(s): 96-1-453