The popular image of the jungle is one of mystery and romance. Kipling, Conrad, Maugham, and hoses of contemporary and older writers, in creating this common picture, have given the general reader vicarious pleasure of travel and adventure in the fascinating and sometimes menacing jungles of the world.

The towering lowland jungle of Guatemala, lavishly wealthy in flora and fauna, fits perfectly into this popular conception. The elements of romance are there; the mystery of a vanished civilization, ruins of ancient cities, lost temples and ceremonial centers, and buried archaeological treasures–all wrapped in the green gloom of exuberant chlorophyll that has run rampant for almost a thousand years.

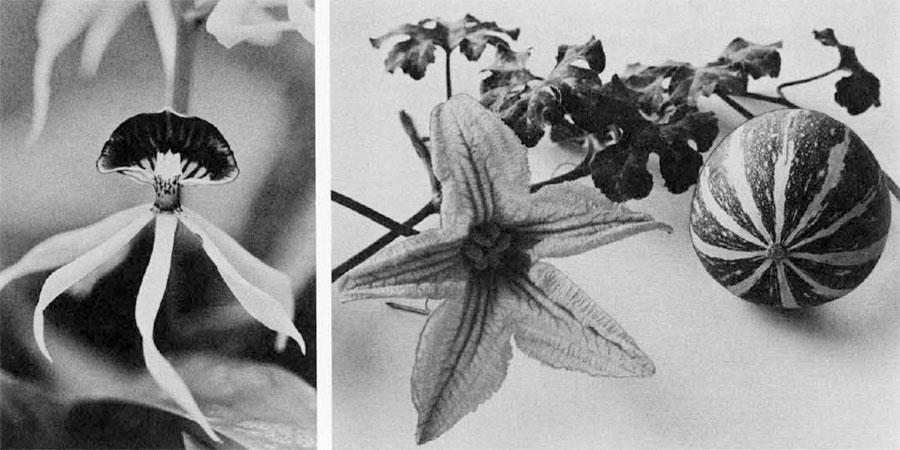

The jungle has its beauty, too. The green gloom is brightened with vivid flashes of color in the plumage of tropical birds and the flowers of exotic plants. Patterns, delicate and exquisite, are common to leaves and in the tracery of fronds and foliage in the shifting mosaics of light and shadow. In all fairness, though, we shall note that the jungle is a trap for the uninitiated and the unwary. The jungle has an arsenal of secret weapons with which it scratches, bites, and usually infects. The jungle humidity is oppressive. And the jungle does have an odor!

There is another image of the Guatemala jungle, one much more realistic than the popular image, but one not nearly so generally held: the image of an important segment of the garden of plant creation of the Western Hemisphere.

With the exception of cereal grains, fruits in general, and a few other crops, our most important vegetables, fiber plants, and corn are native to this hemisphere. Apparently, a majority of these had their origin in the region extending from southern Mexico through northern Central America, a region in which Tikal in the lowlands of the Department of Peten, Guatemala, is centrally located.

Present theories hold that the movement of mankind into this hemisphere was a southward flow from Siberia through the Bering Strait, down the West Coast all the way to Patagonia. The ancient, migrant Mongolians, or their predecessors, found all the essentials of life in southern Mexico and Central America. They settled there, developed an agriculture and, in time, built the Maya civilization, which rested upon the cornerstone of maize.

Cultivated species of the plants that supported their agriculture eventually passed, probably through barter and trade, to all other areas of the hemisphere. Largely, the plants from this garden of plant creation also made possible the rise of two other great civilizations, the Aztec of Mexico and the Inca of Peru. These elementary facts are mentioned to give background significance to the abundant flora of the region. Today the botanist is able to find relicts of ancient Maya agriculture. He also can find, now and then, wild ancestors of the cultivated species.

The living jungle around Tikal has protected and nurtured cotton, sisal, tobacco, beans, squash, pumpkins, sweet potatoes, peppers, avocados, many fruits, nute, ornamental relicts, and other plants of economic importance. Here, indeed, is a laboratory of plant creation, where botanists and other plant scientists still can find primordial germ plasm in abundance.

The importance of this source of germ plasm supply to the highly specialized agriculture of North America cannot be overemphasized. Plant breeders continuously are on the lookout for more hardy strains that they can cross with cultivated forms to increase yields and to strengthen drought tolerance as well as insect and disease resistance.

Population expansion of the world and the growing demands which industry is making upon agriculture have plant scientists searching for species that will meet current and future needs of man, whether for antibiotics, fibers, spices, vegetable oils, better proteins, or ornamentals.

All these economic factors contribute to the importance which the Guatemala jungle holds for our basic industry. The Texas Research Foundation is presently engaged in a survey to determine the extent and the variety of the plant resources of the region and to evaluate the ancient Maya agriculture of the Guatemala lowlands. This survey, centered at Tikal and now in its second year, is being undertaken with the financial assistance of The Rockefeller Foundation of New York. It has the gracious cooperation of the Government of Guatemala.

To date, our plant resources survey has recorded more than two thousand species. Progenitors of cultivated plants are being gathered at Tikal for investigation by plant scientists the world over. That, briefly, is a thumbnail validation of the garden image of the Guatemala jungle.

There is still another image, latent but terrible, lurking in Tikal’s rank undergrowth and in the grotesque roots that now embrace the selfsame altars where ancient Maya priests fostered their people’s faith in their gods of Maize, Sun, Moon, Rain, Earth, and Sky. The image is that of doom–a shattered civilization and the silence of oblivion as the natural and inevitable end for any people, anywhere, who exploit the soil.

That Maya agriculture exploited and exhausted the soil of the region is apparent in giant tree roots writhing and searching for sustenance on the surface of the jungle floor and in the great silt-filled swamps surrounded by low hills which erosion has bared to bedrock. Soil profiles exposed by archaeological excavations show only the thinnest layers of top soil. This is the once fertile land that in the heyday of Tikal a thousand years ago supported possibly two hundred thousand people. Maya agriculture, surely, was far advanced as a practice–but not as a science.

Basically, Maya civilization rested on corn–or maize–and beans, with corn the staple item of diet. As the Maya had no livestock, they depended upon beans to supply the essential proteins which their European contemporaries were obtaining from dairy products and meats.

The Maya cultivated corn and beans through the milpa system of agriculture, a system of temporary farming in jungle clearings, which after two or more years are abandoned. This is the system found everywhere today in tropical lowland forests. In making these clearings, the Maya left those plants and trees that provided food, fruit, building materials, and other needed products. They cut the trees they did not want and piled brush over the fallen trunks and heavy limbs. Later, usually in April, near the end of the dry season which had reduced the piled brush to inflammable material, they fired the heaps. They then planted corn and beans in the clearings by punching holes in the soil with sharp-pointed and fire-tempered sticks.

Crop yields the first and second years in the new clearings usually were good. By the third year, though, weeds and other quick growing tropical plants had returned in sufficient quantities to sap soil nutrients and drive corn and bean yields below the levels of return essential to population support. The Maya then abandoned the infested clearings, selected new milpa sites in the jungle, and repeated the clearing and burning. Subsequently, of course, they were forced to abandon these sites also. In time, often after a period as short as four or five years, the Maya returned to earlier clearings, once more cut the jungle from them, and repeated the burning and planting.

The essential length of time required for the land to renew itself after each abandonment grew longer and longer, even as the population was increasing and demanding more food. In response, the Maya stepped up the tempo of their losing battle with nature by returning to former clearings before the land had renewed itself. Today at nearby Uaxactun, yields of corn in milpas are often so low the second year that the fields are not harvested. That was true in 1960!

In their desperation, the ancient Maya certainly cut all upland forests in ever-widening and overlapping cycles of cultivation. The inevitable result of such frenzied farming should be apparent even to a disinterested observer. Obvious facts point up precisely the chronology of disaster.

The mute and massive widespread ruins with ramifications of viaducts, roads, other public works, and great temples attest to a teeming, virile population. The tremendous amounts of high protein foods which energized such numbers to such physical labors had to come from the soil, for the Maya had no access to extensive marine products. The tragic results of their efforts to grow these foods are still written in the soil, written so indelibly that the flood of the years has not yet washed away the chronicle.

The Maya milpa system with its continuously losing fight against slowly declining crop yields carried within its operation the seed of its own destruction. The practice of using fire to clear the jungle and brush destroyed all surface litter and much of the humus in the soil. During the thousands of years that the Maya followed this practice, they wrought basic physical and chemical changes in the soil. Continuous cropping and erosion surely depleted the vital supply of soil phosphorus. Under the hugh annual rainfall, erosion accelerated in the denuded areas, stripping them of top soil and choking the lowland basins with silt.

This distinctive, shifting agriculture of the Maya also depleted the river plains of the Peten of soil nutrients, particularly phosphorus, and destroyed the physical structure so essential to continued production of deep soils. The level lands, including the deltas, probably degenerated more quickly than the hilly terrain where the limestone substrata from which the soil evolved are much nearer the surface.

The image of this man-wrought destruction in the land of the ancient Maya is a specter that haunts the civilized world today. Here is the tragic story of a people who perished through application of the selfsame force through which they achieved greatness.

The ancestors of the Maya came from the North into literally a furnace of plant creation, where they domesticated useful plants and developed an agriculture which, in turn, enabled them to create a magnificent civilization. But their development of an agriculture skipped the one vital step: the practice of soil and water conservation to maintain soil fertility in perpetuity. How could a people as intelligent and versatile as the Maya obviously were, a people who developed agriculture as far as they did–how could such human beings, creating a highly complex civilization over centuries in time, make such a fatal mistake?

It may be that this mistake provides the answer to the age old riddle, why Tikal and the other great cultural centers of the ancient Maya were abandoned. The faltering of their agricultural economy, basic as it was to Maya civilization, may have coincided with decadence in the social structure, as well as abuses inherent in the narrow dictatorial theocracy which held the culture together. A series of crop failures could have precipitated crises which led to revolution and the final downfall. Although it would not be wise to attribute the disintegration exclusively to a single factor, the failure of Maya agriculture ma well have served as the catalytic agent which led to the ultimate crisis in a tired and degenerating culture. Only thus can we account satisfactorily for the almost simultaneous abandonment of such great centers as Tikal and Piedras Negras with their varied physical environment.

Today the wonderful jungle of Tikal has buried all in a serenity of its own, and it is for man to delve into these mysteries.