Of all the brilliant minds that have lit up the firmament of ancient Maya studies, there is none that arouses as much admiration, inspiration, and outright devotion as Tatiana Proskouriakoff (1909-1985). After seminal studies on the architecture and sculpture of the Maya, Proskouriakoff made her greatest contribution by going against the current and discovering the true literary and historical nature of Maya hieroglyphic writing, which, apart from numbers and the calendar, had been previously deemed impossible to decipher. She thus paved the way for the renaissance of Maya studies that continues to this day.

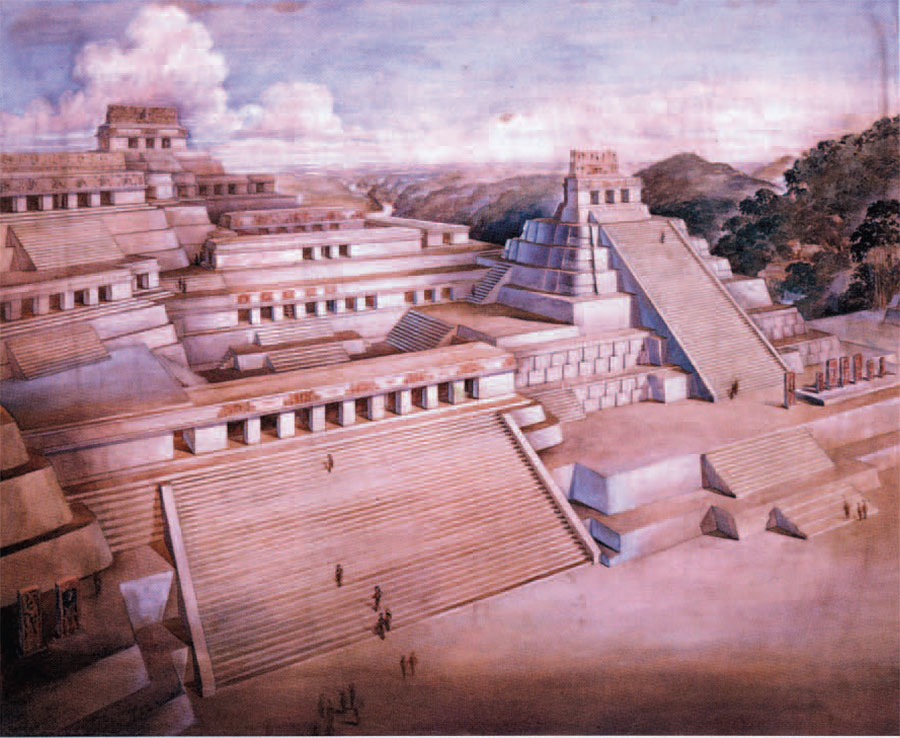

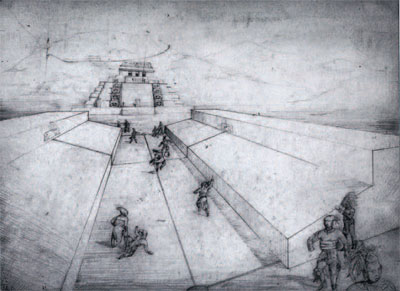

Fate played a crucial role in Proskouriakoff career choice. Born in Tomsk, Siberia, she came to the United States with her family in 19I6, when her father, an engineer, was sent here on a government mission. The Russian revolution made their stay a permanent one. In 1930, Tatiana obtained a B.S. degree in Architecture from Pennsylvania State University. The Great Depression made finding a job hard, so she enrolled in graduate studies in anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania, and volunteered at the University Museum where she prepared archaeological illustrations. The common lore is that after working with Linton Satterthwaite, Assistant Curator of the American Section, Proskouriakoff was invited to join the Museum’s excavations at the Maya site of Piedras Negras, Guatemala, in 1936. Her ability and her dedication to Maya studies eventually secured her positions at the Carnegie Institution in Washington, DC, and Harvard University. despite the fact that she never obtained a degree in the field.

However, a recently discovered news clipping from the Philadelphia Ledger dated December 9, 1930, reveals that Proskouriakoff’s archaeological career could have taken a very different path. When she learned that the Museum was outfitting an archaeological expedition to Persia (modern Iran), she applied for the position of architect on the project. Thirty other students applied for the job. but she was the only woman. The article states that “Men only will accompany the expedition, a fact which barred the participation of the one woman contestant, Tatiana Proskouriakoff,…who, though well qualified for the work, could not be accepted.” In addition, the story noted that “the successful contestant must be one-third architect, one-third surveyor, and one-third red-blooded American.” Her Russian heritage became another factor that kept her from the job.

If Proskouriakoff had obtained the position on the Museum’s Persian Expedition (the first archaeological excavation by Americans in Iran), she might have continued in that field and contributed as much to it as she did to the study of the ancient Maya. In any event, Mayanists are lucky that the prejudices of one group of archaeologists became a blessing for them.

Alex Pezzati

Interim Senior Archivist