Museum Object Number: MS4028

Preface

Undoubtedly the most controversial portrait surviving from antiquity is one which exists in many copies and which has most often been identified as either Menander or Vergil, although speculation has ranged more widely than that. It may well be that various scholars who have accepted one or the other identification have satisfied themselves on the matter and regard the issue as essentially a closed one. But the complexity of the problem and the very heat with which the controversy has been carried on warn against any complacency.

It is, perhaps, an extreme index of the vagaries of art historical analysis that many copies obviously deriving from one prototype can be grouped together as representing a more or less contemporaneous portrait either of a man who lived in the late fourth century B.C.–Menander–or of a man who lived in the first century B.C.–Vergil. To be sure, there are formidable difficulties in arriving at an exact understanding of the course of artistic development in this span of time, not the least being the scarcity of works of art securely dated by external evidence. In any case, the only unprejudiced conclusion which can be drawn from the present state of the matter is that not enough research has yet been carried out, not enough viewpoints have yet been explored; this applies as well, of course, to other aspects of Hellenistic art than merely the portrait under discussion.

As a background to Dr. Fay’s interesting observations, it was my original intention to prepare an up-to-date summary of the Menander-Vergil controversy. This has, however, been rendered unnecessary by Miss Gisela Richter’s recent publication of a copy of “The Head” (as this portrait is familiarly known) in the Dumbarton Oaks collection. It is all the more unnecessary from a personal point of view, since I share–almost to the finest nuances–Miss Richter’s attitude toward the controversy, namely, that–as matters now stand–the most likely but still hypothetical identification of “The Head” as Menander.

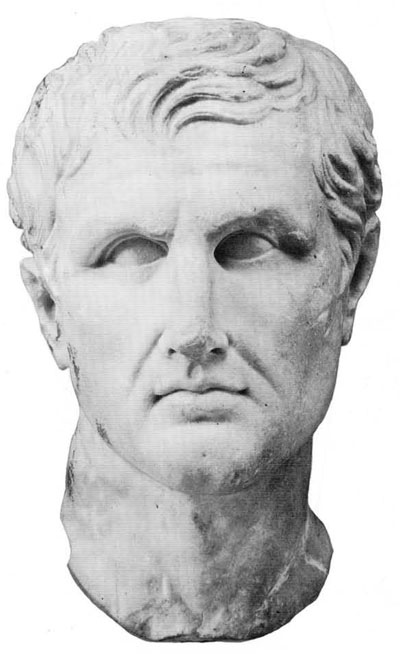

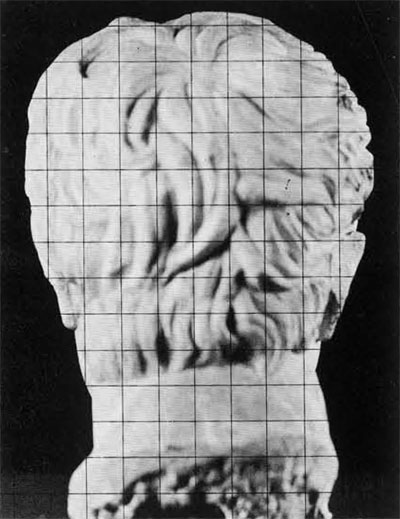

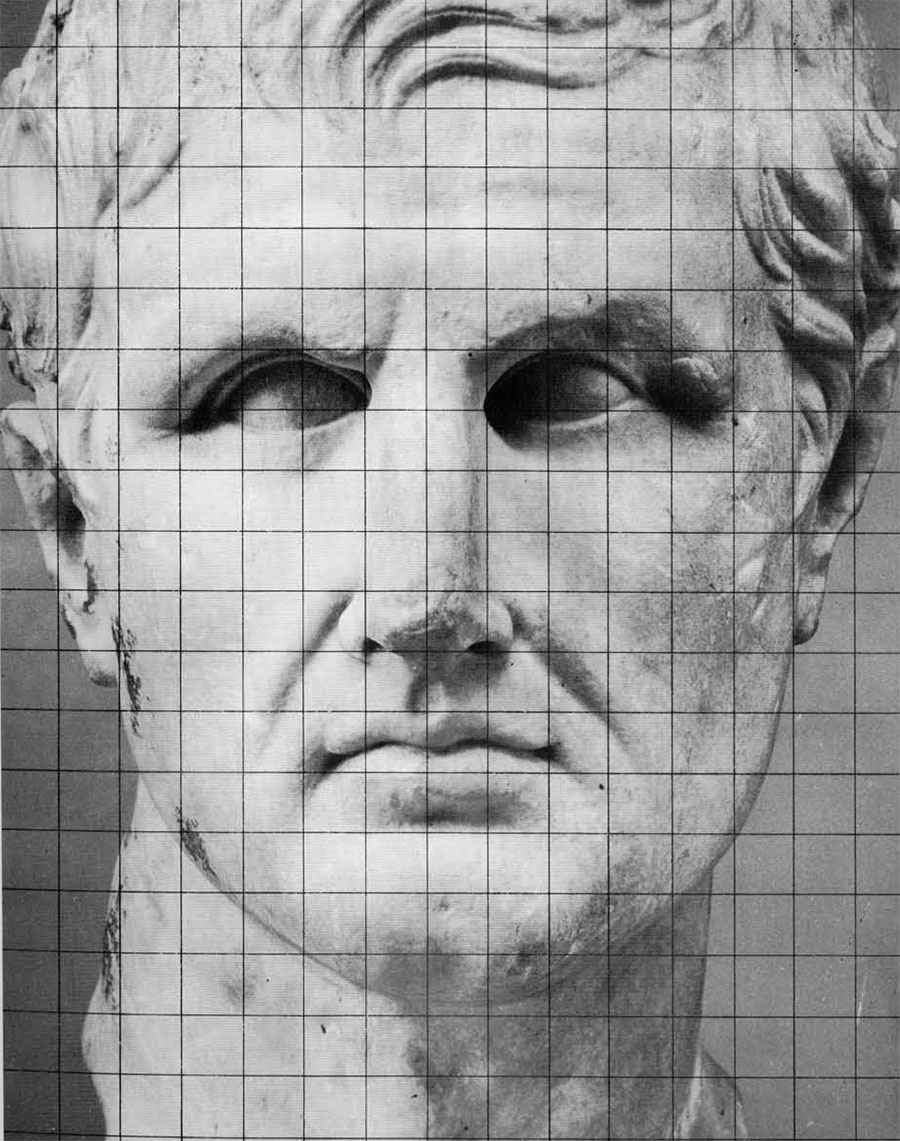

From an art historical point of view, the critical factor in appraising Dr. Fay’s discovery is this: does the Philadelphia head represent an aberration among the copies owing to inferior or inexact workmanship? A final answer to this question could, of course, be established only by an investigation–along the lines of Dr. Fay’s–of many or all of the existing copies. Before such an investigation, which it is not at present in my power to undertake, it is my strong impression that the Philadelphia copy would not prove to be of inferior or inexact workmanship; a general comparison with several easily available published examples such as those in Boston, Venice, Dumbarton Oaks, and the University of Mississippi, reveals at once that all agree in showing the marked underdevelopment of the right side of the face which is so apparent in our Fig. 6.

In any case, in the interpretation of this portrait, archaeologists would be shortsighted to ignore the keen observations of Dr. Fay, who has specialized in studying the structure, and particularly pathological conditions, of the human head. At the very least, he has added a new factor to the problem, requiring a renewed observation of “The Head” from a viewpoint hitherto unexplored.

A Clinical Analysis

“The Head” aroused my interest and curiosity many years ago, because of the obvious disproportions between the two sides of the head, face, and neck. As an occasional visitor to the Museum, while a member of the Medical Faculty of the University of Pennsylvania, and as Assistant to the Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery (1923-1929), I became impressed with the abnormality of this portrait and its similarity ti certain types of neurological patients frequently seen in our clinics and wards today. These patients had suffered a paralysis on one side of the body in early life (cerebral palsy), and survived to grow up with certain characteristic deficiencies in bone and body development localized to the side of the paralysis.

I called attention to the underdevelopment of the features on the right side of the face of this portrait to a number of friends in those days, but more than thirty years passed before I was reminded of these observations and it was suggested that I consult Professor Arnold Post of Haverford College, a widely recognized authority on Menander, the famous Greek poet and writer, to determine whether history records a physical handicap in the poet’s appearance.

This arousal of interest in an old and unsolved question prompted my return to the Museum for a review of the famous head, and there I met Dr. Jack L. Benson whose warm interest and immediate encouragement led to a more detailed study of this fascinating problem.

The characteristic asymmetry in bone development of the head and face, if correctly portrayed, might not only lead to closer identification of the true subject should the historical records reveal a recognized handicap in speech, or in hand or leg function, of Menander, but the portrait itself would then become the careful artistic portrayal of the facial portion of a well known clinical type of spastic paralysis.

During the thirty years that had elapsed between my first observations as to the probably existence of a hemiplegic type of face on the right side of this excellent portrayal, I had come to know in my neurological and neurosurgical practice, large numbers of those who had suffered paralysis by “stroke, tumor, hemorrhage, and in particular, infantile forms of brain injury, with their eventual consequences. At the present time, “cerebral palsy victim” is the term that has been generally used to designate those individuals who have suffered brain injury early in life, later developing characteristic abnormalities with various types and degrees of handicaps or structural inadequacies.

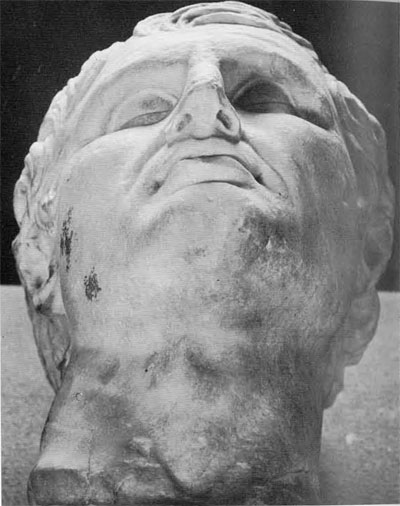

From my examination of “The Head” during these more recent visits to the Museum, it appeared quite obvious that the facial asymmetry originally noted was characteristic of the structural changes noted in patients today who have suffered a localized brain injury early in life. The subject of this portrait probably was a man in his late thirties, manifesting evidence in the bone development and proportions on the right side that he had suffered a form of “cerebral palsy” at least before his tenth year of life. This diagnosis was confirmed when, in the Museum’s photographic studio, we viewed “The Head” from various angles.

From a clinical point of view, the most apparent disproportions and abnormalities are:

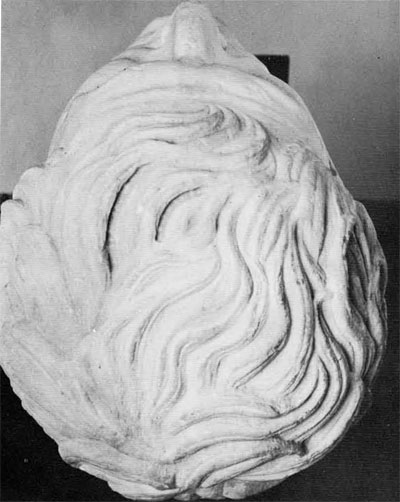

- The frontal bone (forehead) on the right is definitely smaller than on the left (Figs. 2 and 3).

- The right orbit is smaller and the right eyeball recessed (Figs. 3 and 4).

- The right malar bone (cheek) is definitely less prominent than the left (Figs. 2 and 3).

- The right ear is lower than the left, and the external auditory canal level below that of the left (Figs. 1, 4, and 5).

- The expressional fold is drawn outward on the right, and the right halves of the upper and lower lips are smaller and do not match those of the left (Fig. 4).

- The entire conformity of the right face is smaller than the left (Figs. 1 and 4).

- The right side of the neck and tissues of the shoulder are drawn up as seen in the posture of a mild hemiplegic (Figs. 1 and 5).

- The sterno-mastoid muscle is clear-cut on the left, but not revealed, or “lost” in what appears to be contraction of the neck and shoulder tissues on the right (Fig. 1).

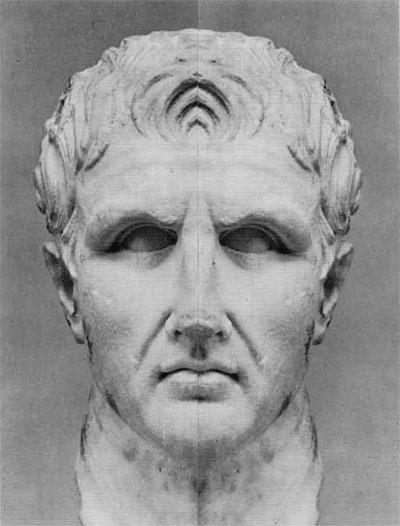

These features are commonly associated with delayed bone development from brain injury or defect arising at birth or in early childhood, affecting the fronto-parieto-motor area of the opposite hemisphere. Structural changes of cranial bones are easily detected by palpation and certain basic measurements, by X-ray studies of the skull, and by composite photographic pictures of the face, comparing the features of one half of the face with those of the other, then duplicating each half and matching them to create two separate reproductions or a full face study (mirrored halves).

Although many normal individuals do not have exactly symmetrical features, the disproportions displayed by the head exceed these limits. In my opinion, they represent the developmental disturbance of the “sensory” type of hemiplegia (parietal area) with a mild motor component. The slightly spastic appearance of the lips and face on the right suggests that some frontal lobe involvement close to the conventional “motor speech” areas was also present. If the person was “right-handed” it might have also affected speech development.

Here then, if we are to read the clinical features of “The Head,” is an ancient portrait of some famed individual who appears to have suffered a brain injury early in life, which influenced the developmental structural characteristics of the right side of the face and neck (and presumable the extremities as well, because selective disturbance of face and neck development alone would be extremely rare) and yet, if fame sufficient to warrant immortalization was responsible for this portrait, intellectual impairment could scarcely have been present. This would suggest the lesion was probably circumscribed and not diffuse, occurred very early in life before the intellectual process became developed, was focal to the parietal area, and not too large. (Porencephalic cyst?)

The frequency of convulsive seizures from lesions of this area would warrant the question as to whether such a person suffered from “spells” or epilepsy. It was Hippocrates (460-400 B.C.) who first accurately described this so-called “Sacred Disease” and gave it the name of epilepsy (seizure). A search, therefore, of contemporary records for a deformity, a limp, or a prominent victim of the “Sacred Disease” epilepsy, might shed further light on the identity of this portrait.

The foregoing considerations pose three questions:

- Is the asymmetry of the face due to some poor or careless quality of the artist’s effort in reproduction? This seems unlikely, as even a novice would be able to create a symmetrical pair of lips, if nothing else.

- Is the disproportion of the face and skull an exact portrayal of a man who had suffered an early form of “cerebral palsy” and later became publicly identified with these obvious characteristic structural deficiencies? The analysis of the entire disproportion of the features would strongly suggest, in my opinion, that not only was the artist excellent in detail portrayal, but also exact in the reproduction of an adult type of developmental deficiency arising from an early parietal type of hemiplegia.

- If the subject of the portrait was famous enough in the third or fourth century B.C. to warrant a marble likeness, and had suffered a right hemiplegia or revealed an obvious developmental handicap throughout life, the natural question would arise as to what historical figure might be identified with certain physical or speech characteristics of moderate right-sided paralysis. A search for such clues or references in the literature and records related to this period could aid in a more definite identification. Conversely, famous characters of the period under consideration who were known to be free of physical handicap might thus be eliminated as potential subjects of “The Head.” Supporting the identification with Menander (343-291 B.C.) is the fact that he is said to have had a peculiarity of gait and possessed a squint.

Appendix

As a kind of appendix to this study, certain information is given here to provide a fuller publication of the Philadelphia copy than has hitherto existed. In addition, a few comments on general problems posed by an interpretation of “The Head” are offered. It is slightly over life size, with a height of fourteen inches. The material is a very fine-grained, dead-white marble with golden and dark brown stains. It appears to have a uniform distribution of fine mica particles. There is a slight chip on the lower lip (which does not alter the case for disproportion presented by Dr. Fay). Other chips exist on the lower part of the nose, over the left eye (increasing the prominence of the eye corner), on both ears, and in the coiffure on the left side. There are several spots in the coiffure which suggest the use of the drill. A golden stain down the face from the forehead to the chin appears to be weathering; there are other traces of this in the coiffure. Dark brown stains characterize the right side; the left side is more weathered, with several small gouge marks which look modern. Discounting external defects, one observes that the sculptor succeeded in portraying the features by means of soft transitions and with a blend of realism and idealism which characterized later fourth century and Early Hellenistic portraiture. There is no compulsion on the basis of technique to assume that the piece is Roman; it would, apart from the contested identification, pass well enough as an original Hellenistic product. It is true that Augustan neo-classicism also idealized portraits; one might, however, refer to the result as a blend of verism and idealism. Furthermore, the stylistic tradition of Hellenistic princely portraiture–particularly observable in the profile view–is so fresh and so strong in the Philadelphia head that I find it difficult to disassociate it from the corresponding period.

The call for extensive and serious study of facial asymmetry and its implications for art history, made some years ago by E. Boehringer, has not, to my knowledge, had any response. Within the framework of such a study, “The Head” would necessarily remain a special problem in view of the underdeveloped right side noticed by Dr. Fay. The general psychic qualities, attributed by Boehringer to the right and left sides of the face, obviously do not apply to “The Head,” nor are they exactly reversed. The mirror view of the right side (Fig. 6) reveals an underdeveloped bony structure of the face (see especially Fig. 2) over which the lips and chin seem tautly drawn, sunken brooding eyes, narrow forehead, and smallish ears. This might well be the material picture of the results of an early illness. These features–taken by themselves–suggest an intense individual with a somewhat choleric temperament. The polar tendency to this seems to appear in the mirror picture of the left side (Fig. 7): the chin is broad, the lips full and relaxed; the eyes appear small and composed; the forehead is broad and culminates in spreading, markedly horizontal locks. The impression given is that of a cold, dispassionate, possibly sensual individual of phlegmatic temperament. In effect, we have before us in this mirrored likeness, an imperturbable mask.

A description like the foregoing, in the absence of easily controlled comparisons, is necessarily to a great extent subjective. Still, to me, the rather contradictory traits revealed in the two mirror views suggest an intense inner life which might well have been artistically creative. And in spite of the underdevelopment of the right half of the face, the adult represented by the portrait is a handsome, sensitive man, one who might well have been at home in a world of wealth, with, and culture.

The existence of polar psychological differences can hardly be denied when one studies Figs. 6 and 7; and a recognition of these may make the observer aware of the personality in control, which somehow kept opposing tendencies working together. It is doubtful if much can be gained by dealing in the rather sweeping generalizations put forward by J. Schwabe. What we see in the mirror pictures of the Philadelphia portrait head, are not male and female halves of an individual, but a range of potential character traits which were welded together dynamically in a unity transcending the sum of the parts (Fig.1).

“Photographic Studies” By: Reuben Goldberg