Wiwanyag Wacipi, the Gazing-at-the-Sun Dance is now the only public ceremony of the Lakota (Teton-Sioux) religion. It is, however, not restricted to this tribe but is also practiced in various forms among the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Crow, Blackfeet, Plains Cree, and Wind River Shoshoni. The Sun Dance is one of the seven major rites of Lakota religion of which only two other rites are known to survive—the purificatory sweat-bath lodge and the vision quest, the seeking of power from the forces which pervade and animate the universe. Besides these rites there are also private shamanistic rituals rooted in the source of power of the medicine man and directed towards healing, prediction, finding lost objects, and thanksgiving.

Origin myths of the Sun Dance account for it in a vision received by a man or as a ceremony given by the buffalo to a man for the people during a time of hunger. In the first account the revelation of the Sun Dance represents the fulfillment of the ritual cycle of the sacred pipe which was brought to the Lakota by the White Buffalo Woman. She explained to them that in time seven ceremonies in which the pipe would serve would be made known to them. The buffalo and the pipe are linked in this myth and in other variants where the pipe is seen as a gift from the buffalo to the people, the buffalo serving as a mediator between Wakan-Tanka, the Great Mystery, and the people. Wakan-Tanka is the essential concept of Lakota religion and is the life-giving force which sustains all being. Everything is seen as partaking of a sacred relationship which is born from the oneness of creation which is a manifestation of Wakan-Tanka. All things come and return to Wakan-Tanka who is all in the universe yet above all, transcending all.

The last old-time Sun Dance was held in 1883 on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota. It was then prohibited by the Bureau of Indian Affairs along with other religious ceremonies, although it is possible that some Sun Dances may have been held surreptitiously during the period when it was under proscription. Under the administration of John Collier as Commissioner of Indian Affairs during the Presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Sun Dance was revived around 1934 although without the self-torture, the piercing of the flesh, which had formerly accompanied it. It was held sporadically from this time onward until about 1958, since when it has been held every year at Pine Ridge and a number of times on the Rosebud Reservation also.

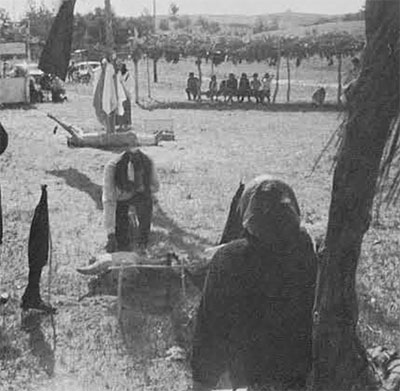

During the summer of 1969 two Sun Dances were held, one at Spring Creek on the Rosebud Reservation in July and the other at Pine Ridge in August. Both reservations are in southwestern South Dakota and adjoin each other. It is the Spring Creek Sun Dance which will be related here.

I was serving as a volunteer worker in the education center in the town of St. Francis on the Rosebud Reservation. Because of my limited knowledge of Lakota, Sun Dance songs here have been drawn from the work of other researchers, all noted in the accompanying “Suggested Reading.” The speaker or the earlier work is given after each quotation.

Several months prior to the midsummer time of the Sun Dance, people of the Spring Creek community had contacted a medicine man on the Pine Ridge Reservation in order to persuade him to lead a Sun Dance in their settlement. This man, Petaga Wakan (Holy Embers), has taken part in several Sun Dances and is a medicine man of the Eagle Pipe Ceremony. He had a son in Vietnam and this is one of the reasons why he would dance this summer. His son has returned safely.

In the beginning Wakan-Tanka gave help to us—our life upon earth and under sky, between them. May He praise the whole world and there may he bestow great help.

Whatever sufferings we have—Vietnam I want a striving for peace; I want Lakota soldiers, American soldiers to return. These things 1 want because I am here, living among these people, praying for them. Well under Wakan-Tanka I am trying. As long as I may humbly do whatever I can do, there from my heart I am trying.

(Petaga Wakan)

Another medicine man who would take part in the Sun Dance is Aopazan (Eagle Feather) from St. Francis on the Rosebud Reservation. He was instrumental in helping to revive the self-torture of the Sun Dance in 1958 and since then he has offered himself many times through the piercing of his flesh. Aopazan is a medicine man of the Yuwipi Ceremony which is prominent on both reservations although particular details of the rite and perhaps interpretation may differ.

Myself, at times I get very discouraged. Is this Sun Dance the truth? At times I reach to the point . . and is there a God? These enter my thinking . . . These are the things. There must be a God. Look at the beautiful world He has created for us. Some of my white brothers have said “You worship the sun.” No, we worship the same almighty God you worship. The sun, Wiwang wacipi, we look at the sun, we gaze at the sun, we admire His work, we thank Him for what He has done for us . . the many things that the Grandfather (WakanTanka ) has done for us.

(Aopazan)

In addition to the two medicine men Petaga Wakan’s wife and grandniece would also dance in the ceremony. Singers and drummers, another medicine man to perform the piercing, and a man to carry the buffalo skull would complete the participants of the Sun Dance.

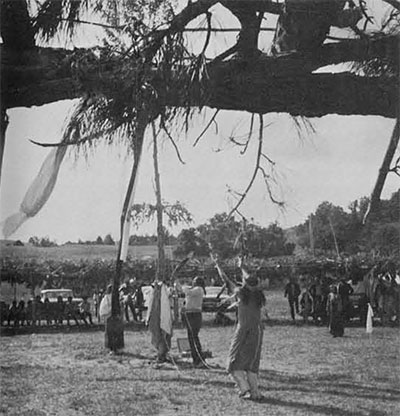

The sacred tree, the center pole, stands in the middle of the Sun Dance circle which is enclosed by pine boughs.

When a year is reached the people gather in one place .. . From there (they go) out in the country where no one lives, where a cottonwood grows and they circle and behold it. Wakan-Tanka has planted that tree, with

His hand it has grown. So the ordinary, the humble man beholds and knows this, being in awe. Wakan-Tanka wants a life like this tree—(one which stands alone; through Him nourished, planted and growing; reverenced by the people)—and the pipe is offered to Him.

(Petaga Wakan)

The cottonwood has special meaning for the Lakota: its bark is the only kind which could be fed to horses; when cut diagonally the wood shows a five-pointed star, the morning star of light and wisdom; the leaf shows the pattern of a moccasin and also, when folded, of a tipi. As waga can, “rustling tree,” it prays, singing in the wind, to Wakan-Tanka. The tree is struck at the four directions, at the places of the four winds, and is chopped down, being gently laid down and held by an opposing brace.

In the ground of Wakan-Tanka, there a tree grew that an ordinary, a humble man took and brought back to where the people live. There in the middle, at the center also, there they dug a place… (Bringing the tree), stopping four times, they placed the tree in this ground. Now over where the people live wasna and (other) food was made and inside the ground which was dug the food was placed for those who died across the previous year up to where they had now reached, for our relatives who let go of life on earth, for all of them.

(Petaga Wakan)

Chokecherry branches are tied about halfway up the tree trunk, cloths with tobacco and possibly a shaman’s medicine are tied at the top of the tree.

The tree with all the calicos and streamers up there—these streamers have a meaning —white, red, black, yellow. You will notice on the west side where the altar is, is black; the north is red; east is yellow; south is white.

(Aopazan)

The sacred tree is Wakan-Tanka joining earth and sky; as Wakan-Tanka it is the center of the universe.

Sacred I stand

Behold me

Was said to me

At the center of the earth

Stand looking around you

Recognizing the tribe

Stand looking around you

Grandfather

At the places of the four winds

May you be reverenced

You made me wear something sacred

The tribe sitting in reverence

They wish to live.

( Densmore 1918 : 119-121 )

On the first day of the dancing the participants prepared in a tipi erected outside the circle, while a fire was started to heat the rocks to be used in the purifying and vitality-giving rites of the sweat lodge. Petaga Wakan went with his pipe to pray at the tree.

Grandfather

A voice I am going to send

Hear me

All over the universe

A voice I am going to send

Hear me Grandfather

I will live

I have said it.

(Densmore 1918:131)

He returned to the tipi and with Aopazan entered the sweat lodge, where both men prayed and smoked the sacred pipe with which one prays for and with all things. Songs were chanted to Wakan-Tanka.

The Sun, the Light of the world,

I hear Him coming

I see His face as He comes

He makes the beings on earth happy,

And they rejoice

0 Wakan-Tanka I offer to You this world

of Light.

(Brown 1967 : 83 )

Emerging into the light the men dressed and joined the women, with all forming a line before the tipi. An elderly man carried the buffalo skull on a bed of sage while the pipes of the men were carried by the women. Holy, soft green sage circled their foreheads, wrists, and ankles. Purifying, cleansing sage, also used in the sweat lodge, joins the dancers to Wakan-Tanka in the circle, which is never ending as are the power and mystery of the Grandfather. The two men have eagle wing-bone whistles to be used in the dancing and Petaga Wakan carried an eagle feather fan. Speaking to the dancers of the holy day this was, Petaga Wakan sang a sacred song marking the holiness of the day and the offering of the pipe to the Grandfather, Wakan-Tanka.

The dancers walked in single file to the opening at the east, making four stops on the way and pausing before entering the Sun Dance ground.

Wakan-Tanka have mercy on us, That our people may live.

(Brown 1953:70)

Making their way in sunwise fashion to the west the dancers stopped here and faced the black flags, two of which marked this direction. (Two flags on sticks about a foot and a half high marked each of the four directions with red at the north, yellow for the east, and white at the south). Petaga Wakan now took the buffalo skull on the bed of sage and placed it before the flags while the man who had carried it left the circle. A little rack was set up to receive the pipes of the dancers and this completed the altar.

Four times to the earth I prayed

A place I will prepare

0 tribe behold!

(Densmore 1918:123)

Off to the northeast the singers and drummers sat outside of the shade and they began singing and drumming after the altar had been constructed. The men blowing upon the eagle-bone whistles, Petaga Wakan led the dancers with his feet moving rhythmically and in harmony with the beat of the drum, his wife, Wanblie Galeshka Pejuta Winyan (Spotted Eagle Medicine Woman) upraising the hoop of sage which she carried, all of the dancers would alternately lift their right, left, then both hands skyward in prayer.

Where holy you behold

In the place where the sun rises Holy may you behold

Where holy you behold

In the place where the sun passes us on his course Holy you behold

Where goodness you behold

At the turning back of the sun

Goodness may you behold.

( Densmore 1918 :138 )

After a cycle of songs ended, Petaga Wakan led Aopazan by his wristlet of sage, followed by the two women, to dance at the north. At times during the dancing Petaga Wakan would dance behind the others or brush them with the eagle-feather fan. The pattern of dancing followed that at the west. When the dancers reached the white south and danced before this direction Petaga Wakan danced around to the altar. Kneeling before the rack upon which his pipe rested, he took it and filled the bowl with tobacco, making offerings of grains to all of the directions, to earth, and to Wakan-Tanka. So was the pipe also offered and then bending over and holding it he prayed. Returning to the south he presented the pipe to Aopazan who now danced to the yellow east, the place where the sun comes upon the world. Here he danced up with the pipe to offer it to another medicine man who kneeled outside the yellow. Three times the pipe was refused as the outstretched hands were drawn hack but on the fourth occasion the pipe was accepted and thus the dancers were permitted to rest. If the pipe had been refused the fourth time the dancers would have had to make another round of the circle. While the dancers moved outside the circle to rest, the pipe was smoked by the musicans. When it completed their circle Petaga Wakan returned it, to the altar, again offering the pipe to the directions.

Entering at the west the women remained at the altar facing inward towards the sacred tree. Both medicine men approached the center and around the tree they wrapped little pouches of tobacco tied in a long string. Near the bottom of the tree where these offerings were placed, the tree was thickened by cloths containing tobacco tied in one of their corners and given by people who asked for the prayers of the dancers. Both men were here at the center to make flesh offerings to Wakan-Tanka. As Petaga Wakan cut little pieces from Aopazan’s left arm, his right one was raised as he called upon the Grandfather for mercy. When the cutting came to his right arm Aopazan uplifted his left arm in his plea. Petaga Wakan smeared the blood along both of Aopazan’s arms with the eagle-feather fan while Aopazan, humble and crying, stood singing to Wakan-Tanka. During the cutting, Petaga Wakan’s grandniece, who was carrying his pipe (which he had given to her when the circle was re-entered), became tired. Upon completing the flesh offerings of Aopazan, Petaga Wakan escorted her to the center where sitting and resting she was brushed with the fan, her fatigue thus being removed. Aopazan now cut from Petaga Wakan’s arms in the same manner and the flesh of both was later placed in a red cloth attached to the other cloth offerings on the tree.

Petaga Wakan addressed the observers of the Sun Dance in Lakota and returned to the west where, with the pipe replaced at the altar, the dancing at the places of the four winds began. This time the offering of the pipe to the other medicine man, Tahca Huste (Lame Deer), came at the south and with Aopazan’s pipe. It was accepted and returned to the altar. The skull and bed of sage, the little rack and the pipes, and the colored flags were removed. With the dancers circling the sacred tree, Petaga Wakan touching his fan to the places of the four winds, all left the ground and returned to the tipi. The first day of the Sun Dance was completed.

Before the sun’s dawning on the second day of the ceremony, Aopazan suffered a heart attack due to exertion in attempting to change a tire on his car. In his place his grandson Canzila, six years old, would dance. Aopazan said of his grandson’s prayers in the sweat lodge that although he was small Canzila would ask Wakan-Tanka that his prayers might be made large. Canzila also took part in the Pine Ridge Sun Dance. Probably this is the only occasion of a Sun Dancer so young. Whereas Aopazan had planned to be pierced on the last day of the Sun Dance this was now impossible. Petaga Wakan would now bear this piercing for himself and Aopazan. The dancing on the second day followed the previous day’s pattern although without any offerings of flesh. Aopazan has said of the dancing at the colored flags:

Black, when you stop (at the) first station, you will accept the black race as your brothers and sisters. Second stop, the red, you will accept the red race as your brothers and sisters. Yellow, the same and the white the same.

(Aopazan)

On the last day while the sun was still low Petaga Wakan came to the center pole where, placing a red figure of a man to the west and a black buffalo figure to the south, he put sage at the base of the sacred tree. Leaving and then returning, touching his pipe to the tree he offered it to the directions beginning with the east.

The light of Wakan-Tanka is upon

my people;

It is making the whole earth bright.

My people are now happy!

All beings that move are rejoicing!

(Brown 1967:91)

Petaga Wakan returned to the tipi where he prepared the sticks which would be used in his piercing, and a fire was kindled for the sweat lodge. Sharpening the sticks, he spoke of his wish that in the piercing they might cause him great pain and in cutting them he had this in mind. He did not want the piercing to be an easy thing.

. . the piercing is really something by it-

self. It’s hard to explain. I could sit here and pierce myself and not feel as bad as what it is at the Sun Dance. The two are different, quite different . . .

(Zimmerly 1969:57)

Medicine roots that had been previously dug up were laid at the bottom of the tree and these would be applied to the wounds made by the piercing. With the heating of the rocks and their placement in the sweat lodge, Petaga Wakan and Canzila entered and used Aopazan’s pipe for the smoking. Singing and praying in the lodge, they emerged shortly and prepared for the final day.

On the last day Petaga Wakan wore eagle feathers in the flesh of his arms. Within the ceremonial ground he represents the eagles with his feathers, their wings, and in the sound of the eagle wing-bone whistle their screaming. With his wife carrying Petaga Wakan’s pipe and Canzila Aopazan’s, the dancers formed a line with Petaga Wakan singing his opening song after speaking to the dancers. The flags had been placed at the directions by a white man. Following the same pattern as the first day the participants began dancing at the west. When this had been completed, Tahca Huste, taking sage from the base of the center pole, wrapping it around Petaga Wakan’s wrist, led him with the other dancers to the north. There he waved his eagle-feather fan around each individual during the dancing. After a complete round had been made the dancers rested. Bringing his pipe to the sacred tree Tahca Huste offered it to the four directions and Wakan-Tanka.

Returning to the circle Petaga Wakan came to the holy tree, touching his pipe to it and then attaching cloth offerings (red, white, yellow, and black) in bundles of four at the places of the four winds. Upon finishing he sat and lay in preparation for the piercing. At the points where he would be pierced red circles had been painted, the red being associated with the thunderbird. With the musicians drumming and chanting all the time, Tahca Huste escorted Canzila to the north, Petaga Wakan’s wife to the east, and his grandniece to the south. Canzila remained dancing and blowing upon an eagle-bone whistle during the piercing. First piercing Petaga Wakan’s right and then his left breast, Tahca Huste rubbed earth, sage, and then the medicine root over each wound. Also rubbed in sage was the stick which was placed through his flesh.

With the tree and Petaga Wakan joined by a rope attached to the stick, Tahca Huste helped him to rise and Petaga Wakan, placing his arms upon the north and south of the tree, leaned his forehead on it. Drum pulsating, eagle-bone whistle wailing, blood running, feet drumming, so Petaga Wakan danced, offering himself to Wakan-Tanka.

Climbing Eagle said this

“Wakan’tanka, pity me, From henceforth

For a long time I will live” He is saying this, and Stands there, enduring

Wakan’tanka

When I pray to him, heard me

Whatever is good

He grants me.

(Densmore 1918:135, 140)

Pulling away, stretching outward, Petaga Wakan broke the bond on his right side. Turning, running outward, stretching back, so the other bond was broken. Now free and dancing skyward and earthward as his hands were raised above and below, he joined the others. All returned to the altar where, dancing and praying, they moved to the holy tree and circled it.

Gathering the ritual equipment, the dancers formed a line at the east and the observers of the ceremony filed past, shaking hands with the dancers and giving thanks. The sacred tree was laid down by the frame of the sweat lodge and its cloth flags and offerings were taken by the people. Donations were made to the dancers and then they retired to rest.

Petaga Wakan has said:

. . in approaching the Sun Dance arena, I forget everything that is about me—somebody talking to me or taking pictures— . . . I feel close to the Maker in heaven what I do, I want that Maker to answer my prayers, reflect what I ask for in the hearts of my people. Each year when I Sun Dance, all through the year . . . I’ve done some good things this winter which I will thank the Maker for when I go to the Sun Dance pole.

Well, if God is good to me, I shall continue in this Sun Dance for as long as I can. If I live a long time, if I should attain to the age of 80 or somewhere, I shall still participate in it—not as a dancer, but I will be on the receiving end of it, where they receive the pipe. I will still have a part in it, working in it.

(Zimmerly 1969:64, 67).