The Disappearance of Colonel Percy H. Fawcett in the jungles of Mato Grosso*, Brazil in 1925 is still headline news. The Lost City of Z, by David Grann, published in 2009, has now been made into a film. At the time, the story of the fearless and obsessive explorer, looking for a lost city in one of the most remote areas on the planet, was followed by newspapers around the world.

*Today, “Mato” is spelled with one “t” in English, but it used to be spelled “Matto.” The expedition used the common spelling of the time: Matto Grosso Expedition.

Fawcett, born in 1867 in Devon, England, led seven successful expeditions to the Amazon between 1906 and 1924. Initially these were funded by the Royal Geographical Society, but later trips were sponsored by newspapers and other businesses. Fawcett’s drive, stamina, and imperviousness to sickness were legendary. Newspaper dispatches followed Fawcett’s fantastic journeys leaving readers enthralled, and later, stunned by his disappearance.

Fawcett was known for his respect for native people. He was also a Spiritualist who had come to imagine an advanced urban civilization deep in the Amazon jungle, possibly with ties to Atlantis. His last trip, made with his eldest son and his son’s best friend, was to discover such a city. However, after one last message on May 29, 1925, in which Fawcett told of preparing to enter uncharted territory, they disappeared without a trace.

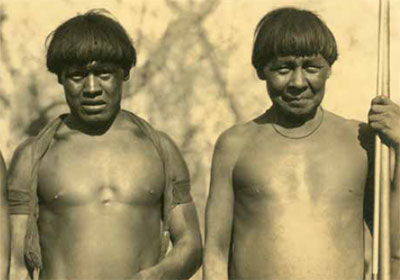

Beginning in 1928, countless rescue expeditions set out to find Fawcett. Many of these “rescuers” also died or disappeared in the jungle. One of the more prominent of these expeditions was mounted in 1928 by Commander George M. Dyott, who claimed to have met Aloike, the chief of the Anuhukua Indians, the person who had most likely killed Fawcett. There were also many sightings of Fawcett over the years, including by a Swiss trapper named Stephen Rattin, who in March 1932 revealed that he had seen Fawcett wearing animal skins and being held captive by Indians.

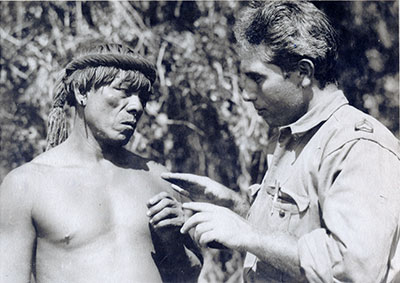

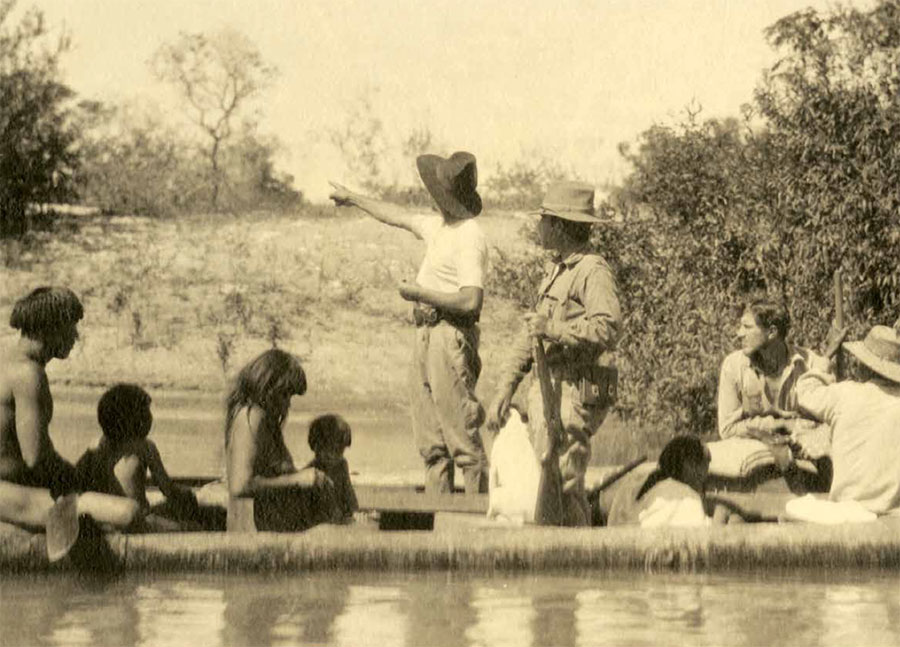

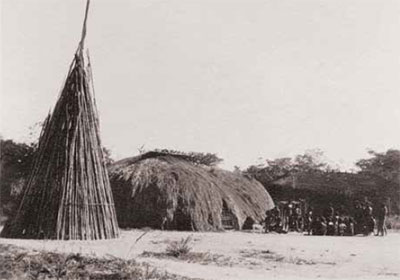

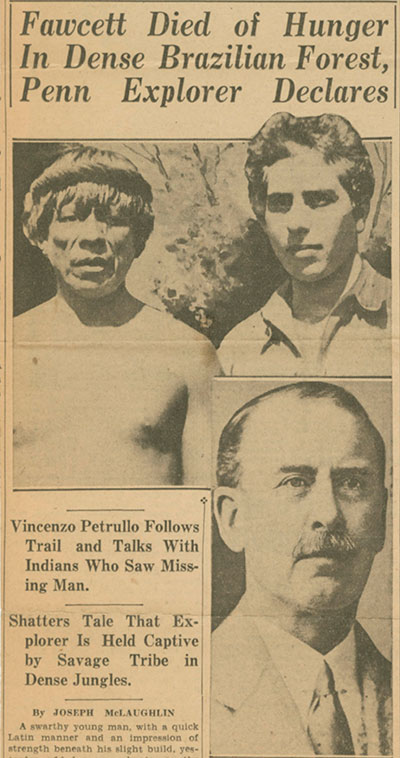

In 1931, the Penn Museum’s own Matto Grosso Expedition had an inadvertent encounter with the Fawcett mystery. Though the purpose of the expedition was to make a documentary of the region, Vincenzo Petrullo, the ethnologist of the group, explored further north toward the Xingu River. There he met Aloike and the other Indians who had last seen Fawcett six years before.

On August 13, 1931, Petrullo writes in his field diary: “At three o’clock stopped for a minute at the point on the east bank [of the Kuluene River] where Fawcet [sic] entered the mato [bush]. Art [Arthur Rossi] took pictures.”

Petrullo fleshes out his story to The Philadelphia Record, April 3, 1932, shortly after Rattin’s claimed sighting: “Current interest in the story…told by a Swiss trapper…urges me to make public this information. I collected it from Indians at the headwaters of the Xingu River, in the Matto Grosso, the point where Colonel Fawcett disappeared. I did so after I found I had unwittingly followed his trail…

“I realized I had been following his trail when I reached the village of the Kalapalus on the Kuluene river, a tributary of the Xingu. Two of the natives came to tell me of the visit and departure of three white men a number of years ago. That having been the second time outsiders had come into their country, the incident was clearly remembered…Briefly, they told how the white men arrived at Kalapalu village in the company of some Anahukua Indians who had guided them from their village on the Kuluseu, a march of four days. The white men carried packs and arms, but no presents for the Indians such as I had. The Kalapalu gave them food, biiju and fish, and in the morning, having failed to dissuade the leader, the older man, from his project, they ferried the three men across the Kuluene River…It was explained to the Indians that by going east a large river would be reached where large canoes could be found which would take the party home. The younger men were ill and were suffering from Borachudo sores [from Black Flies], and apparently were reluctant to go any farther. Subsequently for five days the Kalapalu saw the smoke of the travelers [as they lit a campfire each night]. It is presumed that on the sixth day they reached the forest to the east, for the smoke was not seen any more. Later a party of the Kalapalu…found traces of the camps made but not the white men.”

Petrullo thought that Fawcett had probably “died of thirst, or hunger, or disease. Somewhere in the dense forests to the east of the Kuluene River…I believe it would be impossible for Colonel Fawcett to be alive in that region without knowing it. News travels fast there. Especially news concerning white men, because there are so few of them.”

When asked why Dyott did not learn this story, Petrullo replied: “I don’t think he had any interpreters who could converse with the Kalapalu. Besides the Indians of that region did not like him.”

Regarding Rattin’s sighting the prior month: “Ridiculous.” Petrullo explains that the sighting took place hundreds of miles away, and adds: “And then there is the story of the animal skins. No one wears animal skins in that region. You would die from the stench if not from the heat. The Indians go absolutely naked.”

See Expedition 51.3 (Winter 2009): 6–9 for another story about the Museum’s 1931 Matto Grosso Expedition.