The Body Worlds exhibitions of plastinated human bodies and anatomical specimens by German anatomist Gunther von Hagens are in many ways a distinctly modern phenomenon and yet also closely tied to the past in both the treatment of mummies as showpieces and sources of fascination (see Mitchell article in this issue), and the tradition of artistically rendered anatomical drawings dating back to the Renaissance and continuing into the 19th century. This article traces the aspects of Body Worlds that align with current bioethical discussions about the ownership of bodily tissues (HeLa cells) and control of genomic data (personal genomic testing), while also connecting it to the broader themes running through the various articles in this special issue on mummy studies: immortality and preservation; ritual and ceremony; the control of anatomical knowledge; and sensationalism and voyeurism.

A Modern Enterprise

Body Worlds is a massive international endeavor that, since 1995, has mounted exhibitions covering venues on four continents and drawing over 40 million visitors. Regardless of whether you have personally seen one of the many Body Worlds exhibitions, you most likely have an opinion about them. The commercialization of full body plastinates as realized by von Hagens is a polarizing topic that has generated scores of articles, commentaries, critiques, and accolades. Body Worlds has even made the leap into pop-culture with a scene from Casino Royale (2006) filmed inside one of their exhibitions, and a passing reference made to an exhibition of plastinated human cadavers in The Big Bang Theory (Season 2, Episode 1).

Before launching into a discussion of the meaning and method behind Body Worlds, I must explain my own personal connection to the show. I saw it here in Philadelphia in 2006 at the Franklin Institute. Several features of the show were notable in my memory. First, this exhibition marked a change in tone from the European version, based more on entertainment, to one firmly grounded in science education. Second, I attended the exhibition with a group of fellow anthropologists and scientists. Third, I was visibly pregnant with my first child at the time which, given some of the content, was probably pretty odd! In Europe, the (in)famous pregnant woman plastinate and fetal specimens were part of the main display. In the U.S., these pieces were separated behind a curtained area that you had to go out of your way to see. I found the Body Worlds show to be thoroughly engrossing, tastefully done, and utterly wonderful. My companions bailed on the show long before I did. As a biological anthropologist with training in human anatomy, I am predisposed to appreciate the elegance and skill involved in von Hagens’ dissections. However, I would argue that the exhibition holds meaning on many levels even for those outside the biological sciences, and that seeing a Body Worlds exhibition is very much like seeing any other collection of mummified or preserved remains.

Searching for Immortality

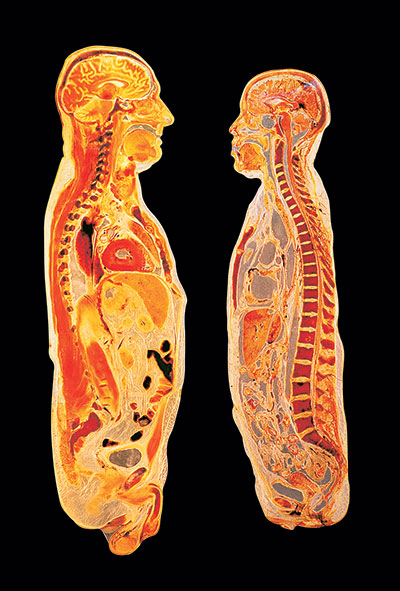

Mummification traditions exist in many cultures using a variety of methods. Preserving our loved ones and making their presence felt after death or preparing them to continue on in the afterlife has been an important part of human tradition. The plastinates of Body Worlds offer a similar if anonymized immortality. Plastinated bodies are even more enduring than either natural or human-made mummies. They can seemingly last forever as 70% of the organic fluid in them has been replaced by plastic, making them simultaneously both natural and synthetic. Here at the Penn Museum, mummies are considered to be cultural artifacts because they have been specially modified by humans during mortuary rituals. The plastination process used by von Hagens sanitizes the messy business of biology, especially decomposition, helping to make death palpable but without offending the senses. Each whole body plastinate represents a significant chunk of time and effort requiring between 1,000 and 1,500 hours of work. As of March 2015, von Hagens has 13,843 still living donors, indicating that there is broad appeal for this sort of postmortem preservation. Essentially, humans are drawn to the notion that they can cheat death by living on in mummified form, including von Hagens, himself, who wants to be plastinated after his death.

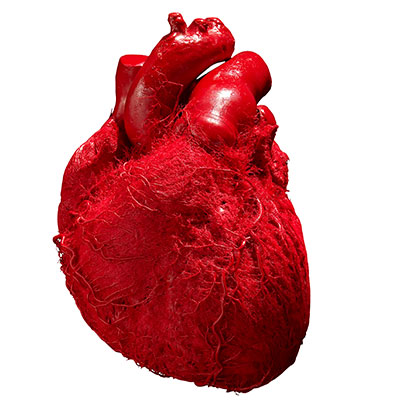

Some of the primary critique of von Hagens’ work has been that it is disrespectful to the dead, especially as his posed plastinates are often rather whimsical, even if they have roots in historical anatomical illustrations or can be argued as displaying functional morphology. He has also had issues with having obtained informed consent from the donors. In the case of the whole body plastinates, full consent has arguably been received. However, this is not true for the fetal or pathological samples that come from older anatomical collections before the days when consent was required. The area of who controls such specimens is tricky as we face issues concerning cell lines such as HeLa (described in the book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks), which was started from a sample taken without consent and has spawned billions of dollars of research. Plastinates that include only part of the body are also not subject to the same rigorous consent process. Under current U.S. law, once part of your body is removed during a medical procedure, such as blood work, biopsy, or surgery, it is no longer yours and what is done to it is not up to you. It is unclear if objections to Body Worlds are based solely on the issue of informed consent or, if by carving the bodies up, von Hagens violates some aspect of understood ritual or ceremony associated with treatment of the deceased. Preferring to keep the bodies intact is reminiscent of the Egyptian belief that the body must be whole to move successfully into the afterlife.

Leading the Charge

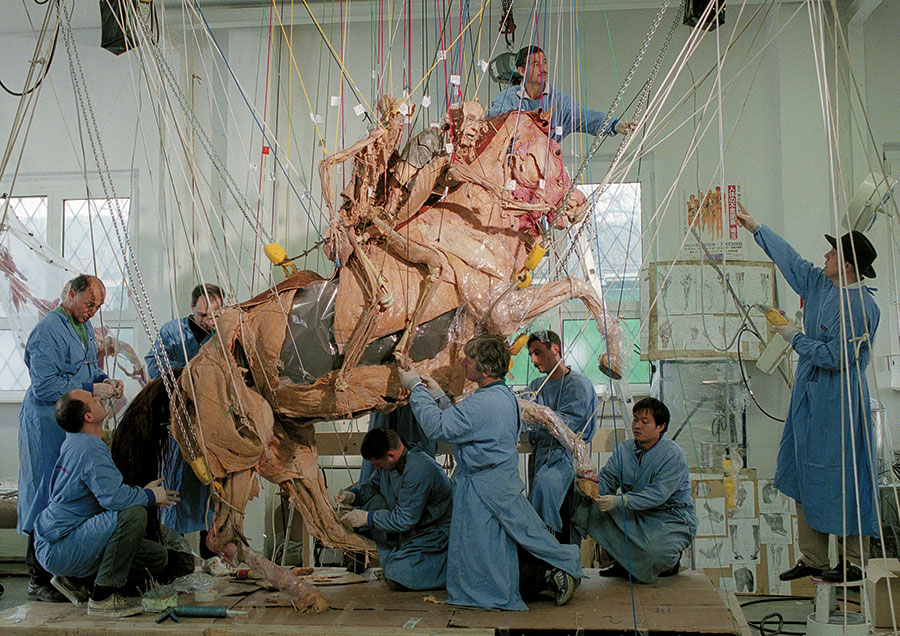

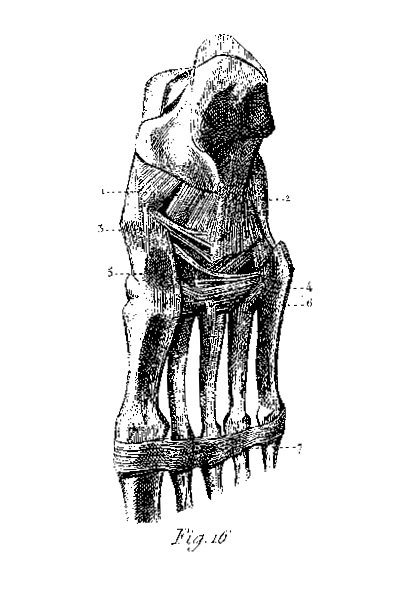

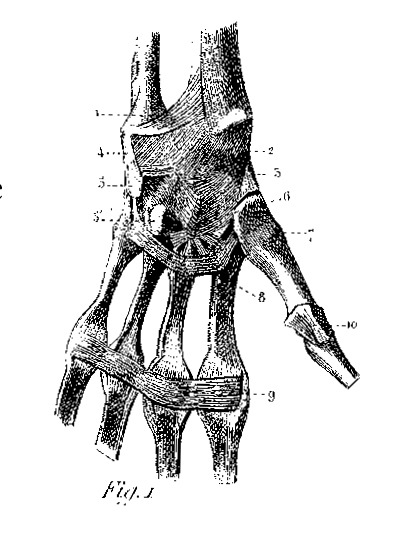

Gunther von Hagens and his team position the mega plastinate “The Rearing Horse with Rider.” Completion of this plastinate took three years.

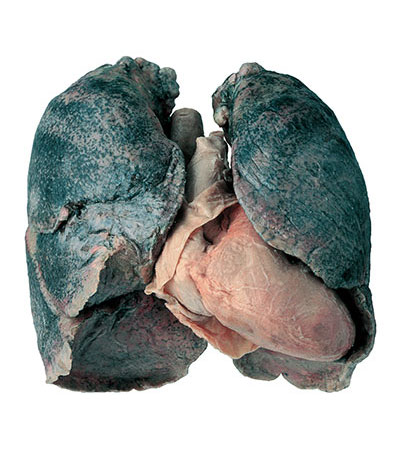

Through time, people have always been keenly interested in the workings of the human body even if their conclusions were sometimes misinformed (the Egyptians removed the brains from mummies partly to prevent rot, but also because they did not think the brain served any important function!). The visual tour of human anatomy and physiology provided by Body Worlds is part of von Hagens’ larger mission to educate and empower people through intimate bodily knowledge. His displays not only show normal human musculature and physiology, but also highlight some of the chronic health issues and evolutionary problems associated with the human body such as obesity, osteoarthritis, and smoker’s lungs.

Just what people are or are not allowed to know about their biology and who controls access to such information is an issue we see cropping up currently, with companies such as 23andMe, offering personal genomic screening for health risks. There is some notion among regulators and biomedical experts that lay people lack the training to properly interpret personal information about their own bodies and that this knowledge could do more harm than good. Control of knowledge is an area under attack as data becomes more abundant, more public, and easier to obtain. As such, von Hagens, a self-proclaimed health educator and democratizer of anatomy, is at the forefront of such discussions. His Body Worlds exhibitions serve the educational aims of museums while providing entertainment value as well, a goal that cannot be said to be outside the mission of exhibitions.

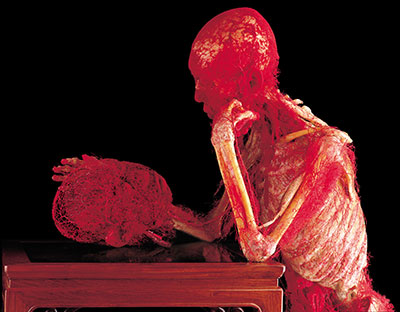

“Poker Playing Trio”

Body Worlds exhibitions include figures in positions that resemble everyday activities. Here, von Hagens injects humor as he depicts a card passed under the table.

A Fascination with Mummies

Modern American culture has an interesting dualism that drives our fascination with mummies both ancient and modern. We are simultaneously both necrophobic and morbidly fascinated by death. In a time where mortality is something which touches our lives infrequently and most often under controlled, medically mediated circumstances or indirectly through news accounts, we find an insatiable audience for movies, television, video games, and books that deal with death, for example, through exaggerated action-filled drama or true crime murder shows. Death as one of the certainties of life is something that intimately ties us to the biological world.

In effect, by highlighting our own frailty and mortality, von Hagens challenges our feeling of superiority over the rest of the animal kingdom. This, of course, also serves to connect us vividly with past humans who have lived and died on our planet. However, as the Body Worlds plastinates are not named individuals, we struggle to make a connection to them—to know their stories. This is an arena where archaeology helps very much to contextualize mummies from past cultures and allows us to understand their traditions and life. Perhaps, this clinical remove is one of the reasons people have difficulty with the Body Worlds exhibitions. They are seeing fellow humans in a most intimate way, but cannot bridge that impersonal barrier.

As an educator and biological anthropologist I feel there is immense value in what von Hagens has done by making human anatomy accessible to everyone. I also understand that he has done himself no service with his occasional outrageous and showman-like antics (e.g. staging the first public autopsy in Britain since 1830 or posing two full-body plastinates in the act of sexual intercourse). Primarily, I see the fascination with the modern mummies of Body Worlds as a similar phenomenon to what keeps people flocking to see the mummies in institutions like the Penn Museum. Whether they are rare traveling mummies like those from the 2011 Silk Road exhibition or our resident Egyptian mummies, there is no question that mummies mesmerize people. Through mummies we are given a window into our own existence, a connection with the past, and a safe vantage point from which to ponder the inevitable consequence of the end of life.

Page Selinsky, PH.D. is Editor, Penn Museum Publications, Consulting Scholar with the Physical Anthropology Section, and guest editor of this special issue of Expedition.