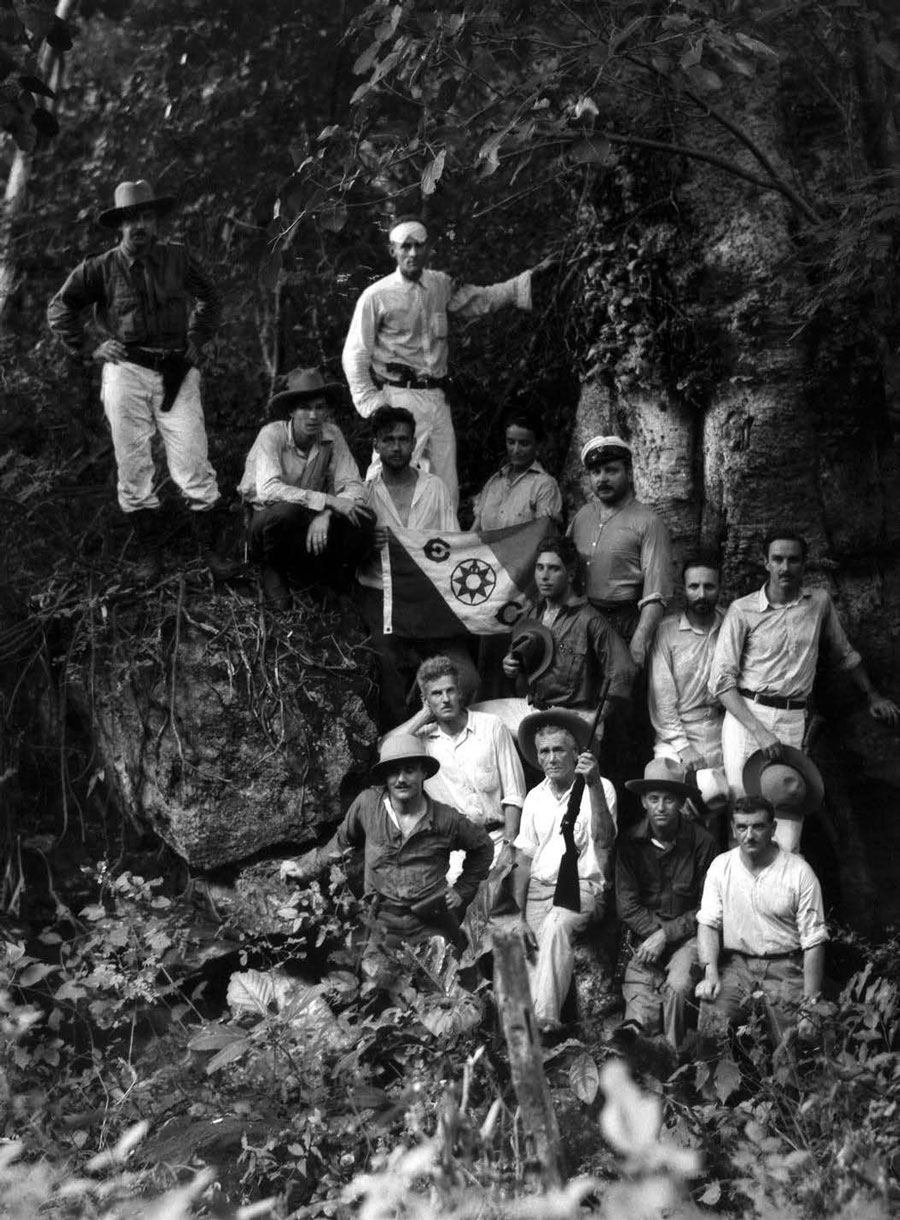

Few expeditions of the Penn Museum have been as colorful as the Matto Grosso Expedition of 1931. Organized by Captain Vladimir Perfilieff, a Russian-born artist and world traveler, and Alexander (Sasha) Siemel, a Latvian who had worked for many years in Brazil as a guide and hunter, this was no ordinary academic venture.

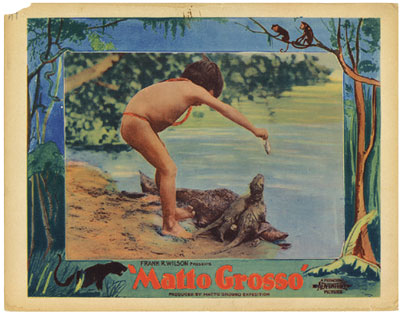

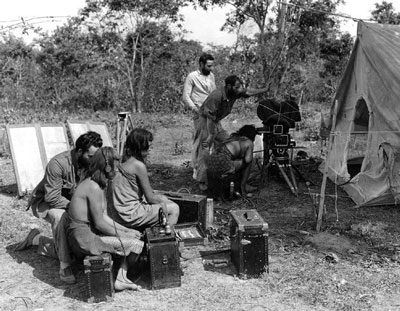

The stated purpose of the expedition was to create a popular and scientific record of the human, animal, and plant life as well as of the geographical features of the Mato Grosso (the region is spelled differently than the expedition) and Xingu regions of Brazil. Thanks to E. R. Fenimore Johnson, son of Eldridge Reeves Johnson, the founder of the Victor Talking Machine Company of Camden, NJ, it was to make pioneering use of modern film and sound equipment to record native life, customs, languages, and music. The documentary produced by the expedition (Matto Grosso: The Great Brazilian Wilder-ness, 1931) was to become the first use of synchronized sound-on-film in a field documentary, and the first such recording of aboriginal languages. It was also the Penn Museum’s one and only Hollywood production.

In the course of his travels, Sasha Siemel had learned the art of spearing a jaguar from the Guató Indians of Brazil, earning him the nickname Tiger Man. It was this skill that Perfilieff wanted to capture on film. Fenimore Johnson, however, envisioned a more comprehensive eth-nological and natural history expedition. He obtained the cooperation of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia and selected Vincenzo Petrullo, a young Italian-born anthropologist who had been trained by Frank G. Speck at the University of Pennsylvania, to di-rect the expedition.

Other members of the expedition included James A. G. Rehn of the Academy of Natural Sciences; George Rawls, actor and hunter; David Newell, reporter for Field and Stream magazine; Floyd D. Crosby, cameraman and director (who had won an Academy Award in cinematog-raphy for the film Tabu, 1931); John S. Clarke, camera-man and manager; Arthur P. Rossi, photographer; and many others.

Fenimore Johnson also contracted with Pan Am to supply the expedition with a Sikorsky S-38 amphibian airplane, to carry supplies to the interior of the Xingu re-gion. The plane was piloted by Charles Lorber (who had previously flown with Charles Lindbergh) and José M. Sauceda, with Hans Frederick Due as the radio operator.

The expedition set sail by steamer from New York on the day after Christmas, 1930. The long trip took the party first to Montevideo, Uruguay, and then upstream to Rancho Descalvados located at the headwaters of the Paraguay River in the heart of the Mato Grosso region, which was to serve as expedition headquarters.

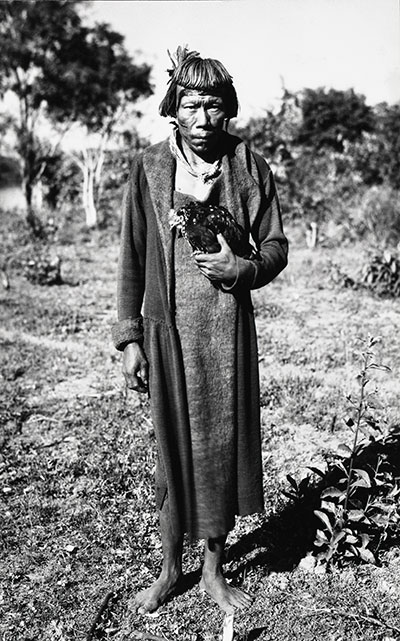

Near the ranch lived members of the Bororo da Campanha, Indians who had long been acculturated by contact with the Western world. Petrullo, according to the prevailing notions of the time, felt that they had forgotten too many of their traditional customs to be of ethnographic value. In June 1931 he therefore resolved to travel farther to the interior, northward to the headwa-ters of the Xingu River, to study groups that had mostly never even met outsiders.

With Lorber piloting the plane and Arthur Rossi as photographer, he made two reconnaissance flights over the area, but the vegetation was too dense to locate native settlements. They finally spotted a village while flying directly overhead, only to be met by a hail of flying arrows. Petrullo, Rossi, and a crew of Brazilians then undertook an overland journey to the same region, with plans to meet up with Johnson and the airplane at the junction of two nearby rivers. They mistook their coordinates, however, and ended up at another river junction 50 miles away.

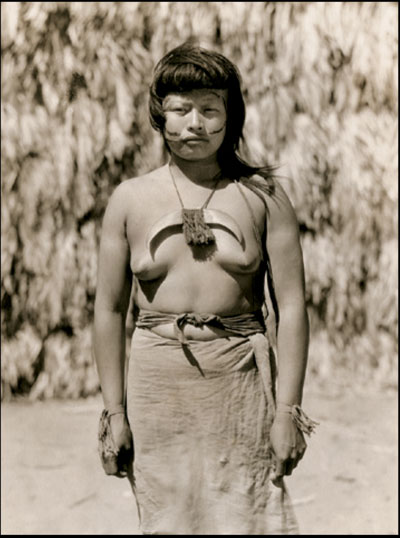

When they finally found their way to the correct meeting spot, a number of native groups, curiosity over-coming their fear, had gathered around the plane. Petrullo was able to make quick comparative ethnological studies by observing the members of the different groups. He and Rossi then traveled to a Yawalapiti village to make further observations. Rossi’s photographs were the first ever taken in this area. Petrullo’s work was hampered by lack of time as well as a lack of interpreters. He hoped that this reconnaissance would allow him to plan a future trip for in-depth study.

Back at Descalvados, the film crew had managed to get pictures of the Bororo in various staged scenes, as well as some of the wildlife. Objects were collected that were brought back to the Museum. Filming Siemel spearing a jaguar, however, had proven elusive. The action was simply too fast. The crew even built a corral with a caged jaguar at one end and placed the camera on an elevated platform, but the jaguar would not come out to face the hunter.

The Matto Grosso film was completed by the end

of the year and released by Principal Adventures Pictures. Though it received some favorable reviews, and is now recognized as an important landmark in film technology, it was not a box-office hit. The film is now available on DVD from the Penn Museum Shop.

Filming & Recording

Aside from the lofty scientific goal of document-ing a threatened culture and way of life, shooting a film in the wild would push the boundaries of movie-making technology that was available in the early 1930s. According to Johnson, this was the first time that talking motion picture equip-ment was brought out of the studio and into the field. The dual aims of authenticity and entertain-ment had to be balanced in the process of filming and, of course, staging events.

Hollywood Goes to Brazil

Bororo Adornment

The American Section at the Penn Museum holds many vibrant examples of personal adornment from the Bororo culture in Brazil, collected during the Matto Grosso Expedition, 1931. Seen here is a pendant (left) made from giant armadillo claws, fiber, shell, and resin (PM object 38-34-193). A headdress dating to about 1920 (right) is made from macaw feathers, harpy eagle feathers, and plant fibers, and is about 19 inches in height (PM object 90-24-3).

ALESSANDRO PEZZATI is the Senior Archivist at the Penn Museum.