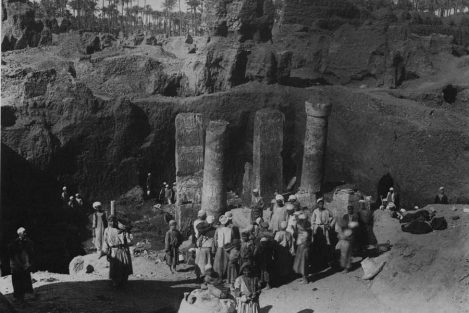

- General view showing progress of the excavations in 1915. The columns and pylon of Merenptah’s palace are in the background, while two doorjambs are visible in the foreground.

-

We have dtermined these limestone pieces to be fragments from the four columns that supported the roof in an outer vestibule in the north entrance to the palace. The pieces show Merentpah giving offerings to the god Ptah, along with lines of hieroglyphic inscriptions. There are some beautiful carvings in raised relief on some of the larger pieces.

Museum Object Number: 84-4-1

-

Hieroglyphs are carved in relief and inlaid with faience and contain the cartouches of Merenptah. We believe the doorway had an opening of 42 inches between the jambs and probably was closed with a single wooden door on bronze hinges. There are no known parts of this doorway on display in the lower Egyptian gallery.

Museum Object Number: E13551C

- The throne room of the palace, looking north from behind the dais out through the central portal (1916).

Egypt is famous for its royal tombs and pyramids, but we know surprisingly little about the ceremonial and political activities of Egypt’s ancient kings, or about their daily lives. In fact, very few royal palaces have been excavated: located on the alluvial plain of the Nile, most have disappeared — swallowed by rising mud, buried under modern towns, or simply destroyed by agricultural activity over the millennia.

The discovery of Merenptah’s palace is especially important because no other royal residence has been found in such a comparatively well preserved condition. Some other New Kingdom (ca. 1570-1070 B.C.) palaces have been excavated, but only the ground plans were recovered because the stone architectural elements and the brick walls were destroyed. For example, Akhenaton’s palace at Tell el Amarna and that of his father, Amenhotep III, at Malkata near Thebes were built on areas never used again after the buildings were abandoned, and so were subjected to extensive stripping and denudation.

The Pharaoh Merenptah, son of Harnesses II, was king of Egypt from 1224-1204 B.C., in the 19th Dynasty. Not long after his death, his palace was swept by a great fire; at the time of the fire the palace was virtually intact. The roof, columns, doorways, and other elements of the building (many gilded and inlaid with multi-colored paste) were buried in a bed of ash and mud which was never disturbed. The ruins of the palace were preserved, at a depth of 16 to 18 feet below the surface at the time of excavation. Thus survived one of the most elaborately decorated buildings that has ever been uncovered in Egypt.

Excavation of the Palace

The University Museum’s Coxe Expedition of 1915 secured a concession for a site at Mem phis, which was the capital of Egypt at the time of Merenptah’s reign and a chief city of ancient Egypt throughout its history. The choice of the site was influenced by a discovery made in 1914 by C. C. Edgar, Inspector of Antiquities for Lower Egypt. He had cleared a small room near the center of the principal mound on the site, and had found painted walls bearing the cartouches of Merenptah. The lavishness of the decoration indicated that the room was part of a royal structure of some kind. The Coxe Expedition proved the site to be that of the pharaoh’s royal palace.

Clarence Fisher excavated the site from 1915 through 1920 (see Figs. 1-3). At this time, many of the palaces stone doorways, lintels and columns were generously assigned to The University Museum by the Egyptian government authorities and were put on exhibit in the Lower Egyptian Gallery of the Museum.

The Merenptah Palace Project

Museum Object Number: E13561

In the summer of 1983, ‘new discoveries’ were made by volunteers working in the Museum basement examining stones for inventory purposes. We assembled from the random piles of stones rare and unusual windows, doorways, lintels, column fragments and bases, and fine reliefs that had never been on display and that had received little study since the early 1920s. This report will outline and explain our project and its discoveries.

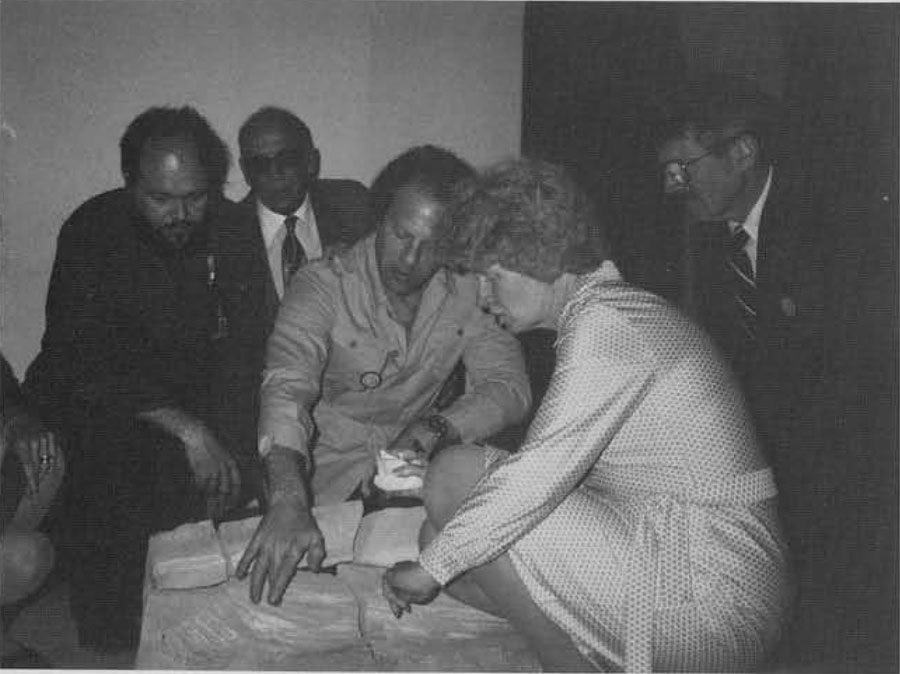

The Project began on August 8 of 1983 with two volunteers, Jay Schwartz and George Brooks, working under the direction of David O’Connor, Associate Curator of the Egyptian Section, and Charles Detwiler, Volunteer Keeper of the Egyptian collection. We started moving out of storage various pieces of stone. All we knew was that they were from Memphis and that they had for the most part not been examined since they were deposited in the Museum basement in the 1920s. To our surprise, the first stones moved appeared to be parts of a window. When we were able to fit some of the pieces together we were elated, for it turned out that this was a very fine and rare window from Merenptah’s palace. We next moved parts of what looked to be the Sun Disk from the center part of a lintel, and once again we found stones that fitted together perfectly. We were intensely excited by the prospects of our ‘find’ and by what possibly lay ahead. The third item to be brought out and assembled was a fine pierced window with the cartouches of Merenptah in rows (Figs. 5,6).

We now realized that we needed more information to enable us to piece together the remaining stones and to understand exactly what we had. On August 25, John Herrmann joined our project, and started to gather from Museum Archives the drawings and field notes made by Clarence Fisher during the 1915-1920 expedition. In this he was assisted by Charles Detwiler.

Our space in the basement was quite crowded by now On October 11, we started to move upstairs to a large classroom on the first floor of the Museum, temporarily allotted to the Project by Dr. Gregory Possehl, Associate Director for Museum Services. By October 15 we had moved tons of stones from storage into the classroom. Some of the pieces were so large and heavy that we needed the help of Museum maintenance people to assist in the moving. From October into December we assembled doorjambs, lintels, windows, relief scenes, column parts, and a column base, all from various locations in the palace. We were amazed of the quality of the carving and inlay on these pieces, and that we had so much that fitted together so well to form monumental pieces.

This work of identification and assembly went on through May of 1984. We had gathered much data from the Archives and the personal field diaries of Clarence Fisher. I spent many hours working in Archives, reading word for word, season after season, the triumphs and failures of the original expedition. I felt that I had an intimate knowledge of the pieces I was handling— almost as if I had dug them from the debris of 3200 years ago myself and was just now getting the pleasure of putting them together. This knowledge enabled me to spot in the various storage areas additional pieces that had until now been classified as of “unknown origin,” but which were without doubt in my eyes from the Merenptah palace.

From January through May, word spread around the Museum of our ‘find, and we had a constant stream of visitors to the classroom to see what was taking place. Finally, in May 1984, with our work completed, David O’Connor hosted a party for 100 Museum members and guests, highlighted by a tour of the class room and an explanation of the work which we had accomplished during the past year.

It is hoped that eventually some of this fascinating material ‘discovered’ in storage can be added to the present exhibit of monumental architecture from Merenptah’s palace already on display in the Lower Egyptian Gallery.