Collectors are, I am convinced, born and not made. Those who have the instinct will collect something, just as surely as birds fly south in the winter; the only question is what it will be. Here extraneous forces, such as space limitation, economic resources, and accessibility to material, unquestionably play an important role, but my guess is that nine times out of ten the field ultimately selected is pure happenstance.

Visitors to our home for the first time invariably ask: “How did you happen to start collecting oriental art?” This is frequently followed by: “Have you traveled a lot in the Orient, or was it a family interest?” The last two suggestions can be dismissed by simple negatives, but the accurate answer to the first query (“Because Dr. Adler’s office is on South Seventeenth Street”) obviously requires some amplification.

When I was a student at the University of Pennsylvania Law School, the process of having your eyes examined was much more time-consuming than it is today. You went to the oculist’s office early in the morning, had a preliminary check-up, and were then turned over to his secretary, whose duty it was to put drops in your eyes every hour for three hours, after which you had the final examination. During this period reading was impossible. Being by nature restless and impatient, I found it intolerable to sit and meditate in the doctor’s waiting room, denied even the dubious diversion of waiting-room magazines. I would therefore window-shop for an hour, return for my drops, and set off for another hour’s stroll. It was on one of these strolls that I saw the pair of turquoise birds in Johnny Mullman’s window.

I never did discover Johnny Mullman’s exact antecedents. He was a dark, wiry little man of vaguely Levantine cast who aways had a faint aroma of musky perfume. His shop consisted of a small, incredibly crowded basement room on the west side of Seventeenth Street just back of where Bonwit-Teller now stands. A Turkish drape only half concealed a day bed in the rear. Whether he actually slept there or whether he had an apartment elsewhere I never knew. He certainly had no great discernment in selecting his stock, most of which was pretty awful, but he did have a genuine, if frequently fallible, feeling for Chinese material. The turquoise phoenixes were about six inches high, of a beautiful blue, mottled with darker matrix. Their fine eighteenth century carving seemed even more elegant in contrast to the contemporary knickknacks which surrounded them. I fell for them completely, and since they were within the range even of a student’s budget, i took them back to Dr. Adler’s for those last drops, and then home. I still have them, my first purchase of oriental art.

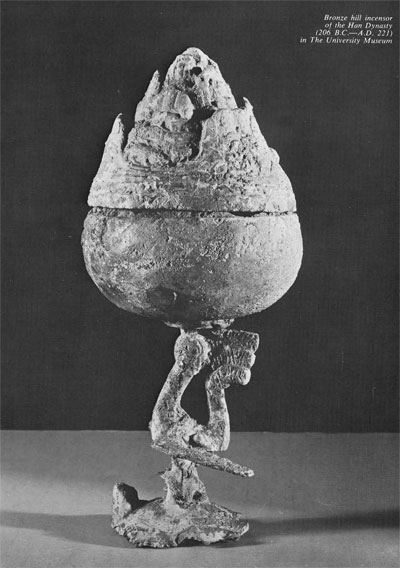

Later I got other things from Johnny–a number of good unglazed T’ang pottery figures, some less good but still respectable glazed pottery vessels, and late jade, amber, and quartz carvings. Most of these have long since gone in the weeding-out process, but a few have stood the test of time. Once Johnny acquired a fine Han bronze hill incensor with tortoise base. It was beyond my resources but I told Horace Jayne about it and it has now been for many years in the University Museum’s collection. I’m sure it was one of its greatest bargains.

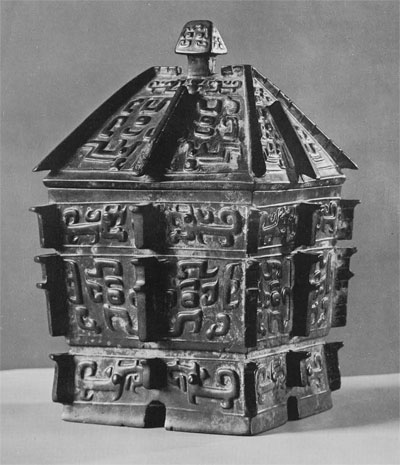

From the collection of Mr. and Mrs. Richard C. Bull.

When I acquired the turquoise birds I was already a hardened collector. I had started at an early age with butterflies and moths and World War I recruiting posters. I had flirted briefly with (among other things) first editions and vintage motion picture advertising posters, and was at the time having simultaneously rather more serious affairs with early phonograph recordings and etchings. My conversion to oriental art was gradual. One afternoon a week after classes I usually spent on lower Pine Street which had then much more to offer than it does now. I soon got to know most of the dealers, who would set aside new material for my next visit.

I can’t honestly say that I ever found any very exciting oriental material on Pine Street, or for that matter in any general antique dealer’s shop. Such material has come to this hemisphere only recently and with full knowledge of its worth. There is no possibility of a forgotten store recovered from some New England attic. I did, however, find things I liked from time to time at auctions in Philadelphia and New York, in a few shops in both cities which specialized in oriental material, and in the hands of traveling oriental students. I even acquired a few things from Gimbel’s in New York when it was disposing of the Hearst collection. When, in the summer of 1937, the Philadelphia Museum of Art held an exhibition entitled, as I recall, “Oriental Art in Private Philadelphia Collections” I was invited to and did lend a score or so of items. It was the first time I had ever been asked to lend to a museum, and I am sure the flattery prodded my interest in the field. My relationship with the Orient remained, however, meretricious; I was not yet prepared to settle down in wedlock.

If Frances Adler, unwittingly, introduced my to oriental art, it was Professor Salmony who, quite wittingly, focussed my field of interest. Dr. Alfred E. Salmony, then Professor of Oriental Art at the Institute of Fine Arts of New York University, was one of the finest, kindest, most patient and most learned men I have ever known. His office and apartment contained one of the best libraries on Asiatic art in existence, and, much rarer, endless files of personally collected photographs of Asiatic material, logically arranged and indexed for easy reference. Most important of all was his encyclopedic knowledge of public and private collections, wherever they might be. While the range of his interests was wide, his greatest love was archaic jade ( a subject on which he has fortunately left three major and many minor publications for posterity) and perhaps his next greatest interest was in the cultural interplat of the various Asian migrations.

Like other private collectors and many scholars, I spent long afternoons in his office studying photographs, texts, or objects he had temporarily for identification or study. With him I visited our major public and private collections. I could always seek his opinion on an object I was considering, knowing that it would not only be frankly given, but that the reasons would be patiently and clearly delineated. After a time, like any good teacher, he would make me express my opinion first, giving the basis for my conclusions, and would then point out where I had learned my lessons, and where I had gone astray. Since his death the extensive new archaeological projects of Communist China have taught us all a great deal for which there was no previous base, and the new material has for the most part supported, rather than refuted, theories which he was the first to admit were necessarily tentative. What little I know about Asian art and culture is due almost entirely to him.

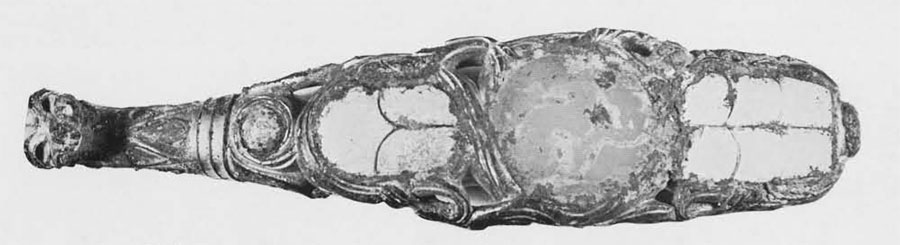

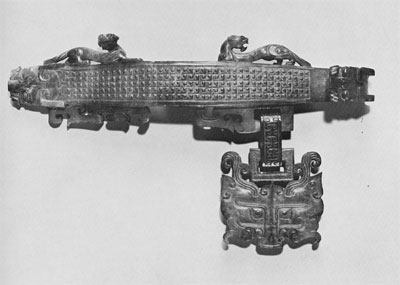

It was with Dr. Salmony’s encouragement that I made my first really major acquisition, a gilt bronze belt hook inlaid with turquoise, jade, and glass from the Late Eastern Chou site of Chin T’sun. We weighed the merits of each archaic jade which came on the market, and I honestly believe he derived as much pleasure from an acquisition as I did. Gradually I became bolder and would make purchases during his long summers abroad. I looked forward with trepidation to the “showing” on his return, but I am glad to say that my batting average, while not perfect, was acceptable. I think his greatest pleasure came from my acquisition (after a two-year courtship) of the Warring States three-piece belt hook carved from a single piece of jade. At the time its form was unique, and he considered it the epitome of Late Eastern Chou jades. Since his death the Communists have found another jade buckle of comparable three-piece form, but quite different in its decorative features.

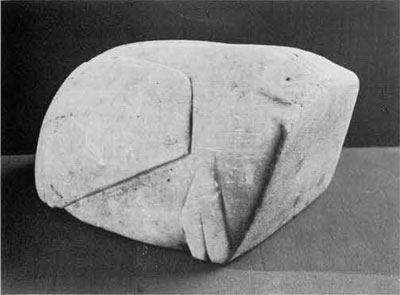

Other early purchases which were favorites of his and remain favorites of mine were an Early Western Chou bronze I of black patina which is unusual for its lack of an overall inscribed background and a pre-Anyang marble frog which would have delighted Brancusi.

Many feel that the greatest thrill in collecting is to find an unrecognized (and correspondingly cheap) treasure in incongruous surroundings. As I have already indicated, this is almost impossible in the field of early Far Eastern art. I have, over a period of 35 years, managed to find at most a dozen really fine pieces whose importance was not appreciated, and these have all been relatively late ceramics which came to the West earlier and in more abundant supply than archaic material. The only available source for good archaic material has always been a handful of leading American, French, Japanese, and English dealers. Attempts to collect in China have generally proved disastrous to the layman. There have come upon the market in recent years a number of collections of “ancient” material purchased at great price by wealthy visitors to China between the two wars– usually reputedly from the private collection of some eminent Hong Kong or Peking dealer who was willing to sell only because he realized the visitor truly appreciated ancient Chinese art. Knowing as much about early artifacts as we do today, the only wonder is how anyone could have been so naive as to have been taken in. A similar (though fortunately far less costly) experience awaited the G.I. who was stationed in the Orient during World War II or the Korean War. I have been asked many times to look at something, Tom, Dick, or Harry brought back from China, Korea, Burma, or Japan. So far I have seen only one worthwhile item–and that was a painting bought in Japan by someone who had been an assistant curator in one of our great museums before his army duty.

Just as exciting, however, as coming across a fine piece in unpromising surroundings is, to me, the rare fun of tracing the prior history of a piece or of finding something obviously interesting but not subject to classification. Except where a piece is acquired from a known collection, prior history is usually a carefully guarded secret. One interesting exception, for me, was a 15th century Balinese stone figure. This had been collected in the early nineteenth century by that romantic British civil servant and adventurer, Raffles, and presented to a provincial British museum which, in the 1950’s decided to trade it in toward a painting. I arrived in the shop of the dealer who had acquired it as it was being unpacked and could not resist it. Years later I found its mate in the Museum of the Royal Tropical Institute in Amsterdam.

The obviously interesting but not classifiable object gives rise to a delightful guessing game, rather like “What in the World?” with no one knowing the correct answer. I have, among other items, a small silver four-horned animal which unquestionably was found in Iran but which Iranian specialists universally disclaim. It bears some resemblance to animals found on Indus Valley seals, and its silver content is not inconsistent with such an origin, but no two experts will hazard the same guess as to its probably provenance or age. Another such object is a terracotta head of a man with goatee, small moustache, and a remarkable pointed, wide-brimmed hat. He has been variously identified as Thai, pre-Columbian, and Indo-Chinese. Such items are always good conversation pieces for the “visiting firemen.”

Good discussion is the collector’s greatest reward. Another thing for which I am indebted to Dr. Salmony was his introducing me to other private collectors and professionals in the Far Eastern and Central Asian fields. Many have become good friends. Sharing of possessions and knowledge is at once stimulating, enlightening, and pleasurable. Being in a large eastern city with fine museums we get many “visiting firemen” whose visits are always a great pleasure, and we in return enjoy the privilege of seeing them on their home ground when we travel. Once in a great while one of them unconsciously poses a problem. I remember entertaining for the first time an important and quite formidable out-of-town visitor. Just as we were plying her with tea and jade our pet pointer bounded in with a half-dead rabbit in his mouth, and laid it hospitably at her feet. Still firmly grasping in one hand the jade she was examining, she patted him with the other, and said, quite affectionately but very firmly: “Nice dog, go away.” He went.

Another special pleasure is relocating a lost friend. C.T. Loo had in his New York shop a pair of Shang jade animals ( a deer and a tiger) in the full round, evidently two of four figures representing the four points of the compass. When I first saw them, in the late forties, I could not afford them, as I had just made another major purchase. When I was in a position to acquire them, they had gone. Many years later, as I was leaving C.T. Loo et. Cie. in Paris, after a rather fruitless afternoon’s review of the available material, Mr. Loo’s daughter remembered that she had stuck away in the vault and forgotten a jade which might interest me. It was my old friend the deer. I do not know the present whereabouts of the tiger.

The unsettled conditions which immediately followed World War II briefly threw an important supply of Chinese art on the world market. Then the United States passed a law forbidding the importation, directly, or indirectly as through European collections, of articles of Chinese origin, regardless of their antiquity, unless it could be proben that they had been outside China prior to 1950. The customs service being unwilling to accept affidavits, regardless of the reputation of the affiant, this means in practice that only artifacts published as being, prior to 1950, in American or European collections can be brought into the United States. Since the Chinese Communist government simultaneously undertook unprecedentedly important archaeological excavations, and quite rightly forbade the exportation of any archaeological material, the practical effect of the American act has been minimal. There are rumors of caches of important material in Hong Kong and Canada awaiting the inevitable modification of the law, but I take them with a very generous grain of salt, since the level of prices in the Japanese and European markets now exceeds those in this country, and must, therefore, have smoked out any significant hoard.

With imports from China cut off, and with the floating supply in the West becoming gradually withdrawn into museum collections, it has for some time been obvious that collecting early Chinese material is essentially a thing of the past, and, like other Orientalists, I have been forced to expand into related fields. Recent acquisitions include a rare tenth or eleventh century Japanese bronze Brahma, an eleventh century Khmer palanquin pole guide, and a Kurumba antelope headdress, as well as a number of Japanese paintings of the seventeenth century or later.

To this account of my collecting, I should like to add a few generalizations on the role of the private collector, who is stronger in numbers than ever before, though necessarily less individually spectacular.

There is a tendency today to feel that it is immoral for a private individual to own an important work of art; that all such works should belong to museums, so that they are readily accessible to the public. Such a feeling is, I submit, unjustified. The assumption that material in private collections is less available to the public than material owned by museums is far from universally true. Most private collectors are extremely generous in lending to special exhibitions which are widely seen by the public, whereas much museum material cannot, because of unfortunate restrictions, be lent for such occasions. The great bulk of museum material is not on public display, but in storerooms which are accessible only upon special arrangement which the great majority of the public do not know can be made, and would hesitate to make if they did. Most private collections are easily seen by any seriously interested person.

In a number of respects the private collector’s approach usually differs from that of a museum curator.

In the first place, the private collector has only his individual taste to satisfy and his collection becomes a reflection of that highly personal characteristic. Conversely, the museum curator must consider not only his own taste, but that of his director, his board and, in many cases, a donor of funds, so that a museum acquisition reflects a composite of various tastes. Since such a composite is always to some degree a compromise, museum acquisitions tend to become relatively conservative.

This tendency is emphasized by the second major difference in approach. The museum aims to present typical examples and as complete coverage as possible in the various fields of art. The average private collector has no such aim, and on the whole tends to acquire the atypical piece which particularly appeals to his individual taste, rather than the typical piece which may better illustrate a particular phase of art.

Thirdly, the museum curator must be far more conservative than the private collector in being certain of the authenticity and, if possible, the precise dating and provenance of his acquisition. Since he is expending public funds, he must be certain that that which he is getting is what it purports to be. For this reason many important items whose authenticity is initially questioned, largely because of their uniqueness, but which are subsequently proven authentic, find their way into private collections rather than museums. Parenthetically, most private collectors today are, if anything, more open-minded than museums in questioning whether or not a particular item is genuine and at least equally anxious to settle any doubt, regardless of the direction.

Lastly, the museum curator has to consider whether a proposed acquisition will be an effective one for display purposes. Many items of great artistic value are so small that hey are ineffective in a large museum room. Others are too subtle to have an immediate impact but can be appreciated only after long and intimate acquaintance, which a museum cannot offer the visitor. In other instances the material must be handled to be appreciated–again an impossibility in a museum. Space limitations also emphasize the tendency of private collectors to concentrate on smaller objects.

There are other areas of difference between museum collecting and private collecting, but those mentioned are sufficient to indicate the fields to which the private collector is naturally drawn.

First and foremost, of course, is the field of contemporary art. Here it is the private collector rather than the museum who is in a position to encourage contemporary artists and to build up collections of their work before they have attained that degree of recognition which would justify museum purchase. Inevitably, the great majority of these artists will never achieve that degree of recognition, but the private collections of the rare few who do must form the necessary source for museum acquisitions in the future.

In the older art forms there have been, at least until recently, and may still be, areas ignored or rather poorly represented in museum collections. Relatively recently, private collectors have played an important part in awakening public and stimulating greater museum interest in such fields as pre-Columbian and African art, Oriental painting, early Japanese ceramics and folk art.

The great contribution of the private collector is his inquiring and adventuresome spirit; his willingness to explore new fields and test problem material in established ones. The world of art would be much narrower, to our great loss, without him.

As H.F.E. Visser said in his Asiatic Art (The Beechhurst Press, 1948, p.11):

“Being myself a museum man, I should rejoice in the fact that the Eumorfopolous, the Raphael and the Winthrop collections went to museums, but it must never be forgotten that private collecting is a great stimulus in all respects. In the end, most of the world’s art treasures will go to museums. We cannot prevent this and certainly do not wand to do so. If, however, on its way from the East to the museum, many an important work could linger for awhile in the house of an inspired collector…this should be encouraged by all concerned. This is the way to keep the flame burning. Museums are highly important, provided they are intelligently managed, but the mission of the private collections and the help they can give to museums should never be underrated.”

Suggested Reading

Werner Speiser, The Art of China. Crown Publishers. 1960

Alfred Salmony, Chinese Jade. Ronald Press, 1963