This article is based on a talk to the University Museum Fellows on November 6, 1975 by Sir John Pope-Hennessy, erstwhile Director of the Victoria and Albert Museum and the British Museum.

From the time that curiosities were first assembled, it has been assumed that the purpose of collecting them was to assuage curiosity. When Tradescant published the catalogue of his own and his father’s collections in 1656, it was described as ‘a benefit to such ingenious persons as would become further enquirers into the various modes of Nature’s admirable works, and the curious Imitators thereof.’ It enumerated first what were described as ‘Natural!’ materials, and then ‘Artificialls, as Utensils, Householdstuffe, Habits, rare curiosities of Art etc.’ The museum of Nicholas Chevalier which opened at Utrecht in the very early eighteenth century was arranged in the same way. There were fish in any quantity—a Zwaard-Visch, whatever that may have been, and a Piscis cornutus, two roses of Jericho, some classical vases, a figure of Vespasian, some Egyptian odds and ends, and a bronze Baptist—and to get into it one paid twopence if one was in company ‘and a single person a schilling.’ In the eighteenth century in most substantial towns, and in university towns without exception, one found private museums of the kind. So general were they that in 1727 there appeared what is, I think, the first book on museology. It was called Museographia, and was printed in Leipzig, and it contained an account of museums open to the public—’Raritaten kabinetten’ they are called—a bibliography of published guides and catalogues (of Aldrovandi’s Museum Metallicum at Bologna, the Museo Moscardo at Padua, the collection of insects at Gotha, and so on), and, most interesting of all, advice about their use. One’s hands must be clean, so that one left no dirty marks upon the specimens. One must be decently dressed (on the principle that ‘Vestis ornat virum’) (one wonders how many modern visitors to the Museum would pass that test). And one need not feel ashamed at asking questions—what objects were? Whether they were natural or artificial? And if they were works of art, by whom they were made, and for what purpose, and exactly why they were to be admired. It was useful to carry a magnifying glass, a ‘gutes Miscroscopium,’ and one should if possible make notes.

For almost a hundred and fifty years these museums continued to proliferate. Some were more specialised. Sir John Soane’s Museum, as is explained in Britton’s book of 1827, was slanted towards architecture. And some reflected a ragbag of personal convictions like Ruskin’s St. George’s Museum at Sheffield, now alas destroyed, which contained crystalline minerals, but no specimens of botany or zoology, and was ‘unencumbered by any life-size statues,’ on account of ‘the Master’s strong conviction and frequent assertion that a Yorkshire market-maid or milk-maid, is better worth looking at than any quantity of Venuses of Melos, while on the other hand a town which is doing its best to extinguish the sun itself cannot be benefited by the possession of statues of Apollo.’ It contained none the less a few works of art, some water-colour copies after Tintoretto, and a number of interesting casts of the still undamaged capitals of the Palazzo Ducale.

More significant than its contents was the conviction from which the Sheffield museum sprang, that “the founding of museums adapted for the general instruction and pleasure of the multitude, and especially the labouring multitude, seems to be in these days a further necessity, to meet which the people themselves may be frankly called upon, and to supply which their own power is perfectly adequate, without waiting the accident or caprice of private philanthropy.” Under George IV Cobbett had opposed the whole concept of public museums. “All that can be done in England,” he said “by squandering upon galleries and museums, is to excite a desire in the vain and frivolous part of the nation to hanker after such things.” But by 1880, when Ruskin wrote, public policy not private philanthropy was the dominating force. In the middle of the nineteenth century the Museum of Ornamental Art at Marlborough House came into existence, and developed into the South Kensington Museum, and between 1851 and the eighteen nineties there were established all but a few of our large regional museums. The movement spread to the United States, where the Chicago Art Institute opened in 1893, and was followed by the Metropolitan Museum in New York, and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. All these were postindustrial revolution institutions, consciously geared to the educational demands of a society that was not entirely different from our own. It was explicitly or tacitly accepted that museums were places in which artefacts or works of art were put to active use.

The British Museum is quite distinct from these late nineteenth century museums. It stems from the tradition of antiquarianism. The original collection of Sir Hans Sloane included a vast variety of artefacts, ranging from natural history at one pole to coins and drawings and objects of curiosity at the other, and on that there was superimposed the acquisition of (to take no more than a few examples) Sir William Hamilton’s collection of vases and antiquities, of Egyptian antiquities (at the very beginning of the nineteenth century), of the Elgin marbles, and of the great Assyrian sculptures. And to house the collections there was constructed what is claimed to be, and no doubt is, the largest neo-classical building in the British Isles. For the first century or more of its existence it was the only great museum that conformed to the precepts laid down by Diderot in the middle of the eighteenth century for a central museum of arts and science. Look where one might, there was no other museum which covered the whole range of knowledge, which housed a great national library, and which formed a living embodiment or recreation of the classical mouseion where works of interest or merit, and books, and scholars were all housed side by side. That did not happen in the Louvre, or in Berlin, or in Vienna, or in any other large city in the world.

A great many of our problems today arise directly from the fact that this idea, this splendid, this intractable idea was a product of its own time. Society might change, but the British Museum remained inviolate. Indeed in its whole history only two major changes have been imposed on it. The first was the separation of the natural history collections from the main museum. Ruskin discusses it in a letter of 1880 on the functions and formation of a museum or picture gallery, and I want to quote the passage here because it was written at a time when the divorce between the collections had been decided on, but was not yet implemented. He refers, you remember, to the “terrific alliance of a giraffe, a hippopotamus and a basking shark” at the top of the stairs, and then goes on: “If I venture to give instances of fault from the British Museum, it is because, on the whole, it is the best ordered and pleasantest institution in all England, and the grandest concentration of the means of human knowledge in the world. And I am heartily sorry for the break-up of it, and augur no good from any changes of arrangement likely to take place in concurrence with Kensington.”

As we all know, Ruskin was wrong. The creation of a physically separate Natural History Museum was of benefit to the natural history collections, to education and to research, and it was of benefit also to the British Museum.

The second great change was the recent administrative separation of the Museum from the Library. That as a matter of fact was something Ruskin envisaged. He believed, at the time that he wrote Modern Art, that “the British Museum ought to contain no books except those of which copies are unique or rare.” It is too early, of course, to say what the consequences of the change will be. My own belief is that they will eventually prove beneficial, and that the Museum will develop in isolation along lines which were not open to it when the Museum and the Library were linked.

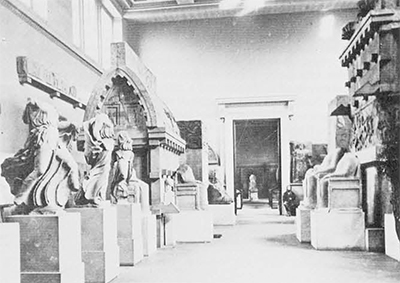

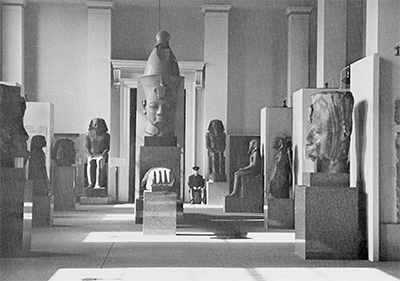

What then are we to make of this encyclopedic heritage? There, projecting on either side of the Museum, you can still see the houses in which so many distinguished scholars lived. One of them was inhabited last year, and now they are all of them turned over to warders’ quarters and offices. Is the neoclassical idea of a group of administrator-scholars living round a library and a museum still viable at the present day? I question if it is. There are places where scholars still live together in fruitful harmony. But I do not feel myself that the collegiate conception of the Museum would contribute very much if it could be revived. The structure of the building is important, not just as architecture, but for the ideas it represents. In the eighteenth century the concept of museums as temples of the muses was a not uncommon one. Those of you who visited the Council of Europe exhibition of the Age of Neoclassicism a couple of years ago will remember that in the architectural annexe there was a section dedicated to them. It showed the plans made by Simonelli in the seventeen seventies for the museum designed to house the Vatican antiquities, the Museo Pio-Clementino, and Klenze’s designs for the Glyptothek in Munich, and Schinkel’s for the Altes Museum in Berlin. The British Museum is a structure of that kind. It is said that it is not an art museum, but the fact remains that the Museum is itself a work of art. I wish that could be restated more emphatically than is at present possible. When I look at its grimy facade, and that splendid gallery where the Egyptian sculpture fights with the architecture and the architecture wins, but only on points, I wonder whether, in this century, it has been treated with quite the solicitude that it deserves. I hope that by next summer Smirke’s front hall will be repristinated, will look once more like the entrance to a great museum, not a railway station waiting room, but that is no more than a start, and a generation of continuing pressure, hopefully public pressure, will be necessary if the neglect of decades (neglect by the appropriate official bodies, not by the Trustees) is to be made good. Obviously buildings where the architecture need not be respected are more flexible. It could indeed be argued that here the architecture, the interior architecture in particular, is really of too high quality for the purpose it is intended to fulfill But I should question that. I believe that the architecture of the Museum is central to its message, and must determine our methods of display.

This thinking affected not only the containing fabric, but the whole nature of the collection. One of the most firmly held beliefs in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was that knowledge was increased by aggregation. Before the invention of photography that, as a general proposition, might have been true. There are still areas in which aggregation is justified. With inscriptions for example, papyri or clay tablets, the more you have, the more you know. On the other hand, there are classes of work, certain Etruscan artefacts for instance, which were produced mechanically, and where the pressure of twenty or thirty identical objects is almost wholly uninformative. One of the great tasks of the Museum in the future must be to determine, in each area of specialty, where aggregation is justified and where it is not. People who direct museums constantly claim that their premises are too small, but the inverse is also sometimes true, that a collection is too large. There are remedies for that, of course (remedies less open to objection than deaccessioning, which is in any case not open to us; the Trustees cannot alienate objects in the collection), the creation of subsidiary museums like the Museum of Mankind, the distribution of loan of groups of works to provincial centres where they will be publicly accessible, a reduction in acquisitions (one looks forward to a situation in which major works, works of exceptional quality and real cultural value, will absorb an even larger part of our small budget than they do now), and last, the application of hard-headed critical thinking to categories of objects which, in some misguided past, were allowed to seep into the collections. One cannot view without disquiet a situation in which so much material is virtually or wholly inaccessible.

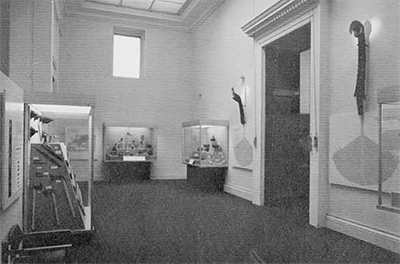

The distinction between art museums and archaeological or cultural or historical museums seems to me simply a semantic difference. I think the trouble really comes from the conviction (and it is quite a modern one) that works of art are made by artists. It is anybody’s guess whether the craftsmen who incised the Lothair crystal, or carved the Nimrud ivories, or made those marvellous Celtic shields, saw themselves in an extra-technical capacity or no. But the fact is that their products are regarded as works of art by us because, in the material culture from which they spring, they are objects so exceptional as to give us—I almost said pleasure, but I know archaeologists don’t like that word—perhaps I should simply say to elicit a strong emotional response. The fact is that there are standards of excellence in almost every field to which ordinary visitors of average perception are liable to respond. And to distinguish the better from the less good is the function of a great part of museum display. I say ‘a great part of museum display’ because archaeological display is also a task in its own right. The two principles are not mutually exclusive. In the Early Medieval galleries at Bloomsbury, you will, for example, find a bay in which the objects, the Byzantine ivories and later Roman silver, are shown as art, and beside it an area, devoted to the Dover Graves, in which the criteria, very properly, are those of archaeology. I have the feeling that where quality criteria can be applied, the public could usefully receive more help. Design is important in museum display, but much more fundamental is the matter of emphasis. There is a premium in directing attention to one object rather than another, in order to ensure that anyone visiting a room leaves it having looked at the main objects it contains, not, in a muddled fashion, at a lot of things that matter less. Going round museums is trying enough, without imposing on the visitor the duty of deciding himself what works are worth looking at and why. The principle of selectivity is already applied in the Greek and Roman and in te admirable Oriental galleries, and I should like to see it introduced more generally into the display.

I am edging here on to a matter which has received relatively little attention in Great Britain, the educational function of museums. When we talk of museum education, we think of those classes of children sitting on aluminum stools before the Grande Jatte in Chicago or walking sedately in double file through through the galleries of the Hermitage. But to my way of thinking the most important form of museum education is unconscious education, the provision of some form of experience, whether aesthetic or historical, that impresses itself on the mind of the spectator without his being fully conscious of exactly what occurs. As soon as something catches our attention, questions, often simple questions, form in our minds. And immense importance attaches to providing answers or what in museums is called labelling. This is a field in which we, in Great Britain, have an awful lot to learn. It is not enough that labels should supply the sort of information that officials think visitors should have; they must envisage the kind of questions visitors are liable to ask. It is no use curators addressing labels to people like themselves. I am a lazy reader, and I have always been a little sceptical about the value of general labels, those pages of Macaulay-like prose which describe the superstitions or the religious convictions, as one is supposed to call them, of the Yoruba, or the presumed export pattern of Dark Age pottery. The intention is all very well, but they seem to me to be based on a mis-estimate of the ordinary person’s reading habits. There is a very real sense in which the combination of minimal academic labels and elaborate wall-notices is anti-educational. What is required is a much more imaginative attitude to the whole thing. And that involves, if I may say so frankly, less cover-up. We know a lot about the material culture of the past, in a factual sense I mean, but there is a great deal we do not know, there are vast areas where speculation masquerades as fact. And the best and most useful labelling is the labelling which comes clean. One of the functions of museums is to crank up people’s minds, and the sovereign way of doing that is to ensure that where there is some serious doubt about the dating of an object, or its place of origin, or the way in which it was produced, that is explained. The legitimate didactic function of museums is, indeed, frustrated if that is not done.

I want also to pose two cognate points which have not, to my mind, been solved in the British Museum nor in any other museum in the world. The first is the need for a more general understanding of technology. There is one very good small section in our Egyptian life room about the techniques used by the Egyptian sculptors. It seems to me that a vast public, which is relatively impercipient of style and perhaps also a trifle vague about millennia, is less interested in the result than in the way in which it was achieved. And I should like to see throughout the entire building small displays in which this absolutely natural curiosity is catered for. The other is the need to make much more consistent efforts to bridge the gap between objects as they are presented in museums and objects as they were intended to be seen. The British Museum does, of course, command the fidelity of an enormous public. The attendance figures, I believe, the third biggest in any museum of art or archaeology in the world. And this means that it is not incumbent on us to take steps to attract a bigger public still, or to stage meretricious exhibitions whose sole purpose is to swell our large attendance figures. Sometimes popular exhibitions whose sole purpose is to swell our large attendance figures. Sometimes popular exhibitions are justified in their own right—the Tutankhamun exhibition was a case in point—but they are not central to our thinking as they must be to museums which depend on exhibitions to bolster up attendances. Over half the attendances at the Metropolitan Museum in New York are geared to the exhibition programme and at South Kensington an active exhibition programme has also proved to be indispensable. But it is not essential in Bloomsbury, where the emphasis must properly rest on exhibitions in relation to the work of the museum, like the recent exhibition of Grimes Graves (and very interesting it was) or the exhibition of late antique gold and silver which will take place two years from now. An exception is the Department of Prints and Drawings, which has shown successively two stupendous exhibitions devoted to Michelangelo—more than two-fifths of Michelangelo’s known drawings are in collections in Great Britain—and to Turner, and where future exhibitions will be dedicated to Claude and Rubens.

It would, I think, be generally felt that the staff of the Museum have a duty not just to their own collections, but to knowledge as a whole, and that their task is to take a wide, imaginative view of the fields for which they are responsible, and to determine how the Museum, with its incomparable physical and technical resources, can best apply itself to extending knowledge and to ascertaining fact. When I say that, it sounds as though I were resisting the claim that a museum is a place of entertainment. And so in a sense I am. For of all the traditions that are embodied in the British Museum, the most important is that the whole institution is geared to knowledge, to scholarship and to research. Nowadays the term ‘scholarship’ is very loosely used. “He is a good scholar,” we say of someone of whom there is indeed little else that can be said. “This is a scholarly book,” we say, meaning that it is stuffed with facts. Unhappily most of the pejorative terms with which the word ‘scholarship’ was hedged round have dropped into disuse. We no longer refer to ‘scholarians’ meaning pedants, nor to ‘scholarism’ meaning pedantry. And the result is that the concept of scholarship embraces a whole range of activities, some of which are useful and constructive, and some of which are eccentric, sterile, and superfluous. It is clearly vital that research should be deliberately directed into channels which seem likely either to extend the bounds of knowledge or at least to yield some positive return. The continuous contact with artefacts implicit in working conditions in museums ought to ensure that, whatever other vices it may have, museum scholarship is not theoretical.

When publication costs rise as they have risen recently, there is a very real risk that the quality and number of learned publications will decrease. To obviate that risk, British Museum Publications Company was established in 1973—an independent Company, with the task of maximising receipts from the sale of postcards and slides and facsimiles, and applying the profits to the subsidy of learned publications. Its terms of reference are very wide—early next year it will issue on the one hand a new and I hope sophisticated Guide to the collections, and on the other the first part of the long delayed report on the Sutton Hoo excavations. You will complain (and rightly) that thirty-five years is a long time to wait for such a publication, but when it does appear it will, I hope, be really definitive.

And perhaps I should say a few words on the area of direct study covered by fieldwork and excavation. At no time in the immediate future will the Museum be in a position to initiate large-scale excavations of its own. But it is involved in a participatory capacity in a quantity of excavation projects, and is responsible for a number of small independent excavations both in France and England. There was a time when excavations in the Near and Middle East could be expected to yield objects for the collections, and they were therefore subsidised from the Museum purchase grant. Now that the export of antiquities is so widely prohibited, that is no longer feasible. But it would be quite wrong if the moral and financial support we give to excavations were curtailed on that account, and they are now supported from other funds since we believe that the Museum’s duty to knowledge exceeds its obligations to its own collections.

I have been speaking for too long, and in summing up I shall say only this. The central problem of people who run museums is to extract the maximum benefit in every area from their collections. No-one today can be unconscious of what museums have to teach, the lessons of compelling relevance that they contain. But it would be altogether wrong if exploitation in this area were to prejudice the status of the museum as a place of learning or to invalidate it as an instrument for original research. My firm conviction is that a compromise between the competing claims of child education, higher education, and original research, between the interests of specialists and of the general public can be achieved, and just because its resources are so great it seems to me that the British Museum should be the forum in which these issues are fought out and a broad pattern which will command the respect of specialists and nonspecialists alike is set.