With this issue of Expedition we are pleased to announce the establishment of a new section on Biblical Archaeology in the University Museum. Professor James B. Pritchard has been appointed Curator in charge and also Professor of Biblical Archaeology in the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Religious Thought.

Although this appointment places a new emphasis on the study of Palestinian Archaeology it continues the tradition of University Museum research in this field. In 1919, George Byron Gordon, then Director of the Museum, and Clarence Fisher, Curator of the Egyptian Section, selected the now famous site of Beisan in Palestine for one of the Museum’s major excavations in the Near East. That was an extension of the Museum’s then current research in Egypt and it was a fortunate choice of sites because Beisan (the Biblical Beth Shan) proved to contain the remains of the only Egyptian fortification of the Empire period yet discovered in Western Asia. Dr. Pritchard himself has been in charge of the University Museum’s excavations at el-Jib in Jordan (Biblical Gibeon, “where the sun stood still”) since 1956.

Palestine is not an area where one expects to find exceptional works of art to add to the impressive collections of ancient art now in the Museum’s galleries, but the historic significance of the collections from Beisan and Gibeon is great and now that the Museum has acquired from Haverford College its renowned collections from the Canaanite site of Beth Shemesh, there is assembled here the most important Palestinian collection in America. With the new emphasis on Biblical Archaeology we expect that the most important objects in these three collections will be presented to the public in a new Palestinian gallery.

Two relatively small and ethnocentric groups of people in the Near East, the Greeks and the Hebrews, early in the first millennium before Christ, assembled their religious and philosophic ideas in written works which have had a profound effect upon the development of Western civilization. The writings of Homer and the Old Testament were, until the last century, also the basis of Western theories about the ancient world. Thus it is not surprising that the original archaeological investigations of Europeans and Americans during the last century were largely concerned with Biblical and Greek history. Today, after the discovery of many other ancient civilizations and records throughout the world, these two exceptional peoples are seen with more perspective in world history. Nevertheless, because of their influence on the history of Western civilization it is natural that an institution like the University Museum should continue to concentrate some of its most important excavations in Palestine and the Hellenic world.

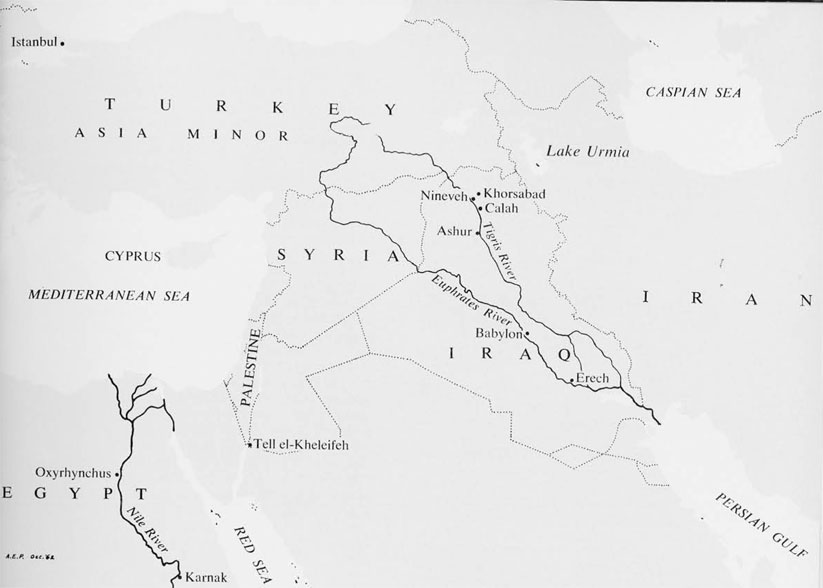

Actually the University Museum’s first excavations were directly concerned with Biblical history. Work at Nippur in southern Babylonia beginning in 1887 was inspired by the then worldwide interest in confirming history recorded in the Old Testament, since in that period Europeans and Americans were learning from excavations in the Near East that the Bible was an historic document based upon two thousand years of recorded history in the Near East, and also that the Homeric writings, once assumed to be only myth and legend, also were based upon historic fact. These writings are the earliest complete documents in the Western world from which scholars reach out to systematize the vast collection of fragmentary inscriptions and documents from the Near East discovered during more than a hundred years of research. Today we recognize the interrelation of all of the ancient peoples of the Near East. Scholars working in distinct fields such as Egypt, Anatolia, Greece, Iran, and Iraq, must be fully aware of the discoveries in each of the other fields in order to interpret discoveries in their own. The University Museum has long concentrated some of its major research in the Near East and therefore all of us welcome the establishment of a specific division on Biblical Archaeology, and the appointment of Professor Pritchard who is so eminently qualified to interpret the complex history of Palestine.

The new Palestinian section, of course, represents only a small part of the Museum’s treasures, which together comprise one of the world’s greatest collections of ancient and primitive art. The collections cover most of the major civilizations–Egypt, China, the Near East, Oceania (Australia and the Islands of the Pacific), the Classical World (Greece, Rome, Crete, Cyprus, Italy), the Americas (from the Eskimos of Alaska and Canada in the north to the Araucanian Indians of Chile), and Africa. They are constantly being added to as a result of the Museum’s current expeditions which in 1962 numbered eight in six countries–Italy, Jordan, Iran, Libya, Egypt, and Guatemala.

This wealth of material–stored and displayed in one place–raises again the question of how museums can best serve the expanding educational needs of our society. In an age of swift communication and wide dissemination of many facets of knowledge, museums have lagged behind in making use of modern techniques to insure that their benefits are more widely available. The basic concept of a museum hasn’t changed much over the centuries–it is a building or buildings to which people generally must come if they wish to view its collections. In recent decades much has been done to bring more people into museums. Exhibitions are more imaginative, the objects more attractively displayed, and they are changed more frequently; the atmosphere of stuffiness and musty scholarship formerly associated with museums largely has disappeared; special programs and workshops have been devised to interest young people and conducted group tours of pupils from nearby schools have become commonplace; gallery tours, concerts, motion pictures, lectures, and social activities have broadened the appeal to adults.

In their efforts to attract more people to their collections, most museums are doing a good job. But there are limitations–mostly geographical–on what can be accomplished by such methods of making museums more effective aids to education. Small beginnings have been made in the area of bringing their benefits to people who cannot now visit museums in person. For many years, the University Museum has sponsored a weekly television program “What in the World” which brings viewers in their own homes an opportunity to see a few of the objects in the Museum’s collections. Other small collections from its storerooms have been made available on a loan basis to institutions in the Delaware Valley area. Visiting lecturers form the Museum staff, armed with color slides, have appeared in convalescent homes and before groups of senior citizens to bring a glimpse of the collections to those who because of age or infirmity cannot visit the Museum in person.

But these are small contributions compared with the enormous possibilities. The next great advance for museums, I am convinced, will be to take a substantial part of their collections out of the galleries and make them available to a vastly larger number of persons living at much greater distances.

Fortunately, this is a problem in which the Pennsylvania General Assembly, on its own initiative, has taken an interest. This past summer, a Task Force of the Assembly, composed of six State Senators and six members of the House of Representatives, has been studying the possibilities of accomplishing just that. The legislators believe that the people of the whole state should profit from what has become a world-famous institution located in Philadelphia. One suggestion being considered is that extensive exhibitions of objects from the past should be circulated throughout the schools and museums of the state. Another, more novel, suggestion is that the University Museum equip several mobile museums to travel throughout the more rural areas. Both of these suggestions are exciting and seem to offer tremendous opportunities–but they are costly.

The Museum’s excavations and research during the past seventy-five years have been financed by provate funds, and we expect that they will continue to be so financed. But the responsibility of making available to schools and other public institutions of the state the great resources of the Museum which are waiting to be tapped for educational purposes is a public one. We welcome the interest of the legislators and pledge the cooperation of the Museum staff in helping them to accomplish their aims.