During the 2016 field season at La Florida, a fascinating discovery was made. A large stela with the carved image of a royal woman was revealed just inches below the surface. Who was this mystery queen and what can this monument tell us about La Florida’s political dynasty?

The Classic Maya site of La Florida (La Flo-REE-da) is located on the banks of the San Pedro River in northwestern Peten, Guatemala. First recorded by the archaeologist Edwin Shook in his 1943 field notes, the site has been visited by several archaeologists over the years, including Sylvanus Morely and Ian Graham, two giants in the field of Maya archaeology. None of these visitors stayed for more than a few days, however, and it was not until 2014 that the La Florida Archaeology Project was formed to systematically study the site. We soon discovered that La Florida was much more extensive than previously supposed, with multiple architectural complexes arranged on both shores of the San Pedro River. The administrative relationship of these complexes is uncertain, but a new stela might shed light on this question.

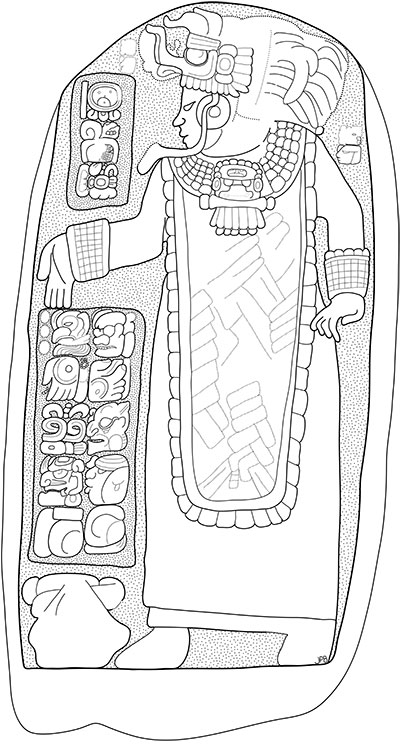

The discovery of Stela 16 extends the written history of the site by 20 years. This monument depicts a royal woman conducting a calendar ritual. While the accompanying text gives us a clear date, the woman’s identity remains enigmatic.

The Site of La Florida

From 1943 to 2014, the only area of La Florida recognized by archaeologists was a large architectural group located on the south side of the river in the modern town of El Naranjo. This part of the site contains 15 stelae and 9 altars, many with valuable information about the site’s dynastic history. The group also contains a royal palace, elite residential groups, and three ceremonial plazas. It overlooks a sheltered river inlet that may have served as a port for canoes traveling on the San Pedro River. When Shook visited this part of the site in 1943, it was occupied by a remote ranch. Today, it lies in the large and growing town of El Naranjo. For this reason, we call it the El Naranjo group.

In 2014, we realized that two additional groups had been overlooked by archaeologists. The El Niño group, located on a ranch on the north side of the river, was probably an elite residential group. The Santa Marta group, located in the village of the same name on the north side of the river, contains ceremonial structures and residential mounds. We identified three new altars, all of which appeared uncarved. Santa Marta also had its own river access—a gently sloped bank with abundant ceramics on the surface. Careful mapping of these three groups in 2015 revealed that they were placed for maximum visibility around a series of river bends. Thus, while only about 2 km apart as the crow flies, the El Naranjo and Santa Marta Groups are approximately 4 km apart by canoe. By strategically distributing settlement along the river, the area’s inhabitants would have had advanced warning of approaching merchants or armies. But how were these different parts of La Florida administered? Who lived in the royal palace in El Naranjo, and how closely did they control the goings-on in Santa Marta?

Classic Kingdoms

La Florida was located on the San Pedro River in northwestern Guatemala. It was an active player in Classic Maya politics. Here, sites in green represent probable allies, while Yaxchilan, in red, was a frequent antagonist. Sites in black represent other Classic Maya sites in the region. To the west of La Florida, the San Pedro and Usumacinta Rivers flow down onto the Tabasco Plain.

The Ancient Kingdom of Namaan

Though Maya epigraphers had long suspected it, Stanley Guenter was the first to demonstrate that La Florida was the seat of the Namaan kingdom, a polity mentioned in inscriptions across the Maya lowlands. During a visit to the site, he confirmed that La Florida Stela 7, located in the El Naranjo Group, gave the title of the local ruler as k’uhul Namaan ajaw, “god-like lord of Namaan.”

Using the inscriptions of La Florida and those of other sites, it is possible to reconstruct a dynastic history that begins sometime around 600 CE or slightly earlier and ends around 800 CE. This recorded history corresponds neatly to the archaeological record at the site. In 2016, the project conducted surface collections and opened six 1 x 1.5 m excavation units in plazas and open areas in the El Naranjo and Santa Marta Groups. We collected 1,412 ceramic sherds over the course of the season. Luckily for us, there has been extensive research at other nearby sites with which we could compare the material. For example, the Penn Museum has a large collection of ceramics from the nearby site of Piedras Negras, excavated in the 1930s, that had already been classified. We studied and photographed sherds from this collection prior to the 2016 field season. We also consulted comparative material from the nearby site of La Joyanca.

In most of the areas of the site that we excavated, the earliest use of plaza spaces began around 600 CE or slightly earlier. While the site may have had a small, earlier occupation, there appeared to be an explosion of activity at the turn of the 7th century. Not only does this match the known dynastic history of the Namaan kingdom, it corresponds to a period of increased political activity in the bordering region of Tabasco, Mexico. Between 518 and 795, the powerful kingdoms of Piedras Negras, Palenque, and Calakmul vied for control of this region.

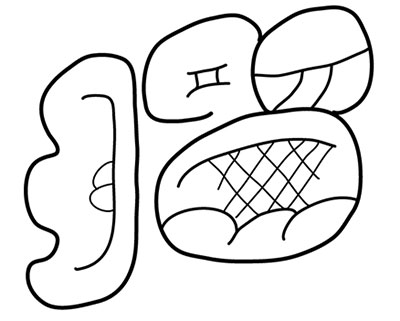

emblem glyph. The top one was found on one of the shell plaques from the tomb of Piedras Negras

ruler K’inich Yo’Nal Ahk II, PM object L-27-41/2.

La Florida shows evidence for economic exchange with Tabasco. We recovered small amounts of Fine Orange pottery from Tabasco, but interestingly, only in the Santa Marta group. However, the El Naranjo Group showed other signs of cultural interaction with Tabasco, namely the presence of Jonuta-style figurines, some of them imported, others local copies. The Tabascan site of Pomona also mentions Namaan rulers in its inscriptions, indicating a political relationship between the two sites. This pattern suggests that elite and diplomatic relations between La Florida and Tabasco were managed in El Naranjo, while trade in more pedestrian products was managed in Santa Marta.

The presence of material culture from Tabasco at La Florida, as well as the attempts of other powerful polities to control the region starting in the 6th century, point to the importance of the region in the overall Maya economy. Tabasco was well suited for growing cacao, the bean from which cocoa and chocolate is made. Colonial- era records indicate that the region produced over 11 million cacao beans in annual tribute to the Spanish authorities, not including any grown for local consumption. Chocolate was used in ancient Mesoamerica not only to make a ceremonial beverage, but as currency in market transactions and tribute arrangements. Thus, the appearance of the Namaan dynasty in the late 6th century, and the simultaneous burst of building activity at La Florida, may be part of a wider rush into a new chocolate market.

La Florida maintained other political alliances as well, as far north as Campeche—possibly the site of Calakmul; as far south as Zaculeu in the Guatemalan Highlands; and as far east as Motul de San Jose on Lake Peten Itza. The Namaan kingdom had an especially strong relationship with Piedras Negras, located on the Usumacinta River. In 706, a young woman from Namaan named Lady Winikhaab Ajaw married Piedras Negras ruler K’inich Yo’Nal Ahk II. She achieved great prominence on her husband’s monuments and inscriptions, which was unusual for Maya queens.

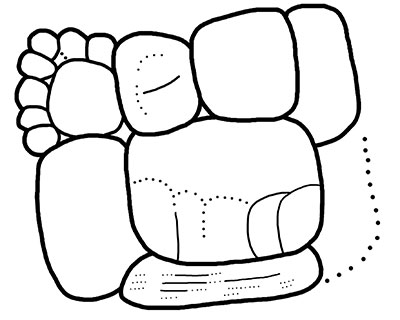

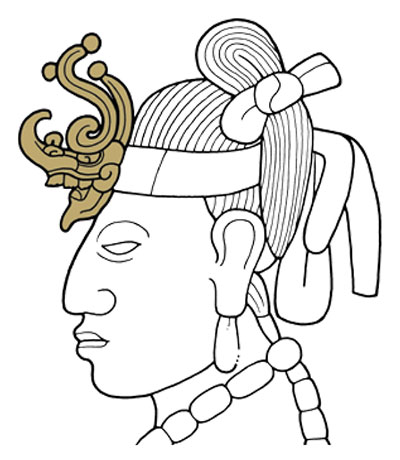

Another prominent queen appears at La Florida itself. Stela 9 depicts a woman, Lady Chak, performing a calendar ritual in 731. She is described as the mother of king K’ahk’ [?] Chan Yopaat, who ruled for at least 35 years. As Penn Museum Associate Curator Dr. Simon Martin notes, her enormous royal headdress contains unusually prominent huun jewels. These anthropomorphic adornments, usually carved from green jade, were affixed to the barkcloth headbands of royalty and symbolized the authority of the ruler.

Waterway Travel

Building La Florida

La Florida has three known architectural groups. The El Naranjo Group is the largest of these and contains the royal palace, ritual plazas, and carved monuments. The Santa Marta Group is smaller, but also contains public architecture. The El Niño Group is the smallest, and contains several elite residences.

Excavating Mounds

right: Overtaken by centuries of native plant growth, researchers excavate Maya mounds to study the architecture beneath, as seen here at La Florida (circle inset) and the neighboring site of La Joyanca.

La Florida Stela 16: A Surprising Discovery

The 2016 field season took an unexpected turn when we discovered Stela 16 while working in the Santa Marta Group. The stela was lying face-up on top of a 3-meterhigh platform, buried under a few inches of rocks and dirt. Once set into a room of the superstructure, the stela had lain undisturbed since the roof and walls had collapsed over it. We had noted the presence of the completely eroded Altar K on the same structure in 2014. But we—along with generations of farmers who plant on this part of the site—had failed to notice the top of Stela 16 peeking out from under the dirt. This year, however, we noted the large, rounded shape of the stone, and the corner of a carved glyph.

in Maya art. Drawing by Simon Martin.

When we cleared the dirt off Stela 16, we immediately noticed its similarity to Stela 9. It too depicted a woman performing a calendar ritual, striking the exact same pose and wearing a nearly identical outfit. Its text gives more detail about the event depicted: in 785 CE, or 9.17.15.0.0 in the Maya Long Count calendar, this woman scattered droplets of incense and bathed three deities. These were the two Paddler Gods, who are best known for paddling the Maize God to the underworld in their mythical canoe. Joining them in the bathing ritual was the Wind God.

The date on Stela 16 makes it the latest known inscription at the site by 20 years. We know from an inscription at Yaxchilan—La Florida’s perpetual enemy— that there was a war between the sites as late as 796, indicating that the kingdom continued on for at least 11 years after Stela 16 was carved. However, no record of La Florida’s rulers exists after this war, and it is possible that the kingdom ceased to exist after this point.

Who was the woman depicted on Stela 16? The text does not give her names or titles; perhaps the inscription originally continued onto the now erased Altar K. Though her headdress is too eroded to see whether she wore the huun jewels, her costume is otherwise identical to that of Lady Chak on Stela 9. Could they be the same woman? We know that Lady Chak was the mother of ruler K’ahk [?] Chan Yopaat. And we know that on Stela 7, carved in 766, this ruler is described as a “4 K’atun Lord,” or a ruler at least 60 years old. The latest he could have been born, therefore, was in 706. Royal Maya women sometimes married at an extremely young age—for example, Lady Winikhaab Ajaw of Namaan married the Piedras Negras ruler when she was just 12 years old. Probably the latest that Lady Chak could have been born was 13 years before her son, or 693 at the latest. Therefore, Lady Chak would be at least 92 years old when Stela 16 was carved. Such longevity is rare, but not unheard of in Maya inscriptions. Lady Pakal of Yaxchilan died in 705 after living at least 98 years.

Stela 16 gives us a new hint about the relationship between the El Naranjo Group and the Santa Marta Group. The similarity between the two stelae suggests that, if not depicting the same woman, both wear the same regalia, passed down within the royal family. The representation of this family at the Santa Marta Group points to a system of direct administration by the royal palace, not a subsidiary family of elite governors. While the two groups probably served different economic functions, therefore, the display of Stela 16 let everyone know who was in charge.

The Queen of La Florida

Stela 16, discovered in 2016, was lying face-up on top of a 3-meter-high platform, buried under a few inches of rocks and dirt. This monument depicts a royal woman conducting a calendar ritual. While the accompanying text gives us a clear date of 785 CE, the woman’s identity remains enigmatic. We have taken to informally referring to the stela as Dona Benita, in honor of the owner of the land where it was found.

Plans for the Future

There is much left to discover at La Florida-Namaan. We will continue to study Stela 16 and look for more monuments hidden at the site. In upcoming seasons, we plan to excavate the site’s residential and port areas in the hope of understanding its trade relationships. We will also investigate the site’s monumental architecture to better understand the explosion in building activity that began around 600 CE. This riverine kingdom still has more to tell us about Classic Maya trade and politics.

JOANNE BARON, PH.D., is a Consulting Scholar (Penn Cultural Heritage Center) at the Penn Museum and Director of the La Florida Archaeology Project.

Acknowledgements

The La Florida Archaeology Project is co-directed by Liliana Padilla and Christopher Martinez. Students Joshua Freedline, Walter Ochoa, Arielle Pierson, and José Subuyuj took part in the investigations described here. Our local assistants René Aguilar, Carlos E. Vargas, Carlos U. Vargas, and Francisco Tomás were also instrumental in our success. We are especially grateful to Benita Estrada, owner of the land on which Stela 16 was found, and to her family, for their enthusiasm and support. The project has been funded by the National Geographic Society, the Rust Family Foundation, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, and the Penn Museum.

For Further Reading

Jørgensen, M.S. and G. Krempel. “The Late Classic Maya Court of Namaan (La Florida, Guatemala),” in Palaces and Courtly Culture in Ancient Mesoamerica, edited by J.N. Knub, C. Helmke, and J. Nielsen, pp. 91–110. Oxford, UK: Archaeopress, 2014.

Krempel, G. “Notes on Stela 2 of La Florida, Peten, Guatemala.” Mexicon XXXIII (2011): 1, pp. 7–10.

Lopes, L. The Maan Polity in Maya Inscriptions. Unpublished manuscript, 2003, available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/2847093_The_Maan_Polity_in_Maya_Inscriptions, accessed 8/2/2013.

Martin, S., and N. Grube. Chronicle of Maya Kings and Queens, 2nd edition. New York: Thames and Hudson, 2008.

Stuart, D. “The Inscriptions on Four Shell Plaques from Piedras Negras, Guatemala,” in Fourth Palenque Round Table, 1980, edited by E.P. Benson, pp. 175–183. San Francisco: Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute. 1985.