As tourism has steadily increased in the Pacific, the sale of local handicrafts has become a profitable source of income for islanders. Among the handicrafts to be found in airport shops throughout Micronesia is the storyboard, Palau’s unique contribution to what has been termed “airport art.” Although the tourist may recognize that the board tells a traditional story in pictographic and representational form, he is unlikely to realize that it is a modern descendant of a traditional architectural form. Its architectural parents were the carved beams and gables of the bai, a men’s club house which traditionally formed the social nucleus for males in a Palauan community.

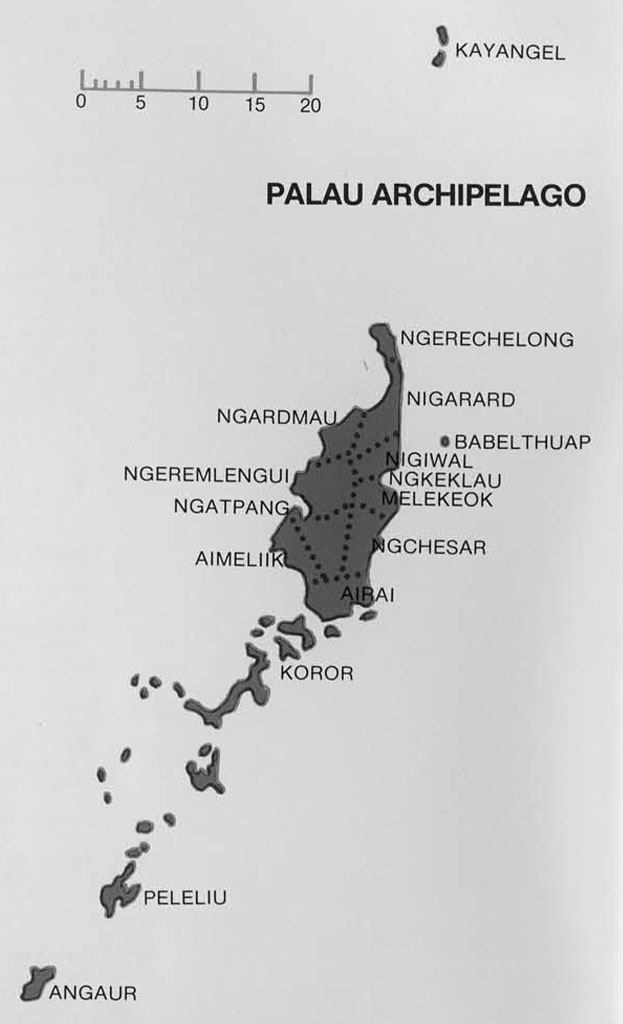

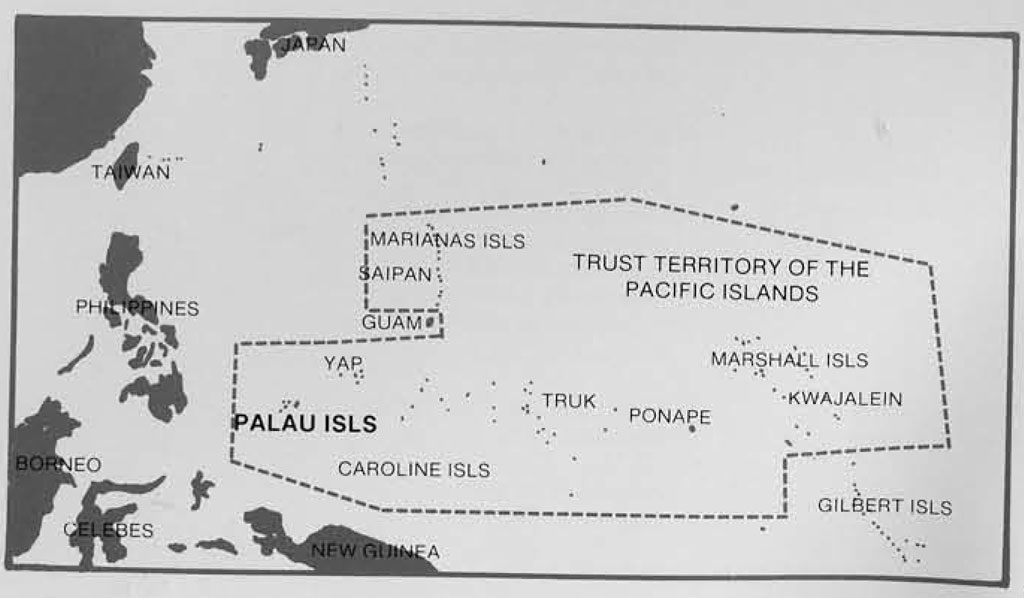

The Palau Archipelago is the westernmost group of islands in the Western Carolines (Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands), just north of the equator and 500 miles east of Mindanao. Archaeological data suggest that Palau’s location, tropical climate and rich sea life may have attracted settlement as early as 1800-1500 B.C. Since that time, Palau has been augmented by people, ideas or artifacts from Melanesia, Indonesia, Malaysia and the southern Philippines. By the time of initial Western contact (1783), Palau was described as a highly stratified society divided into competing, warring confederacies of shifting alliances.

From the time of recorded contact until the present, Palauan currency (udoud) has been an important economic and social aspect of Palauan life. This currency, consisting of a limited amount of small beads and bars of glass and minerals, was introduced at some unknown time into Palau, possibly coming from the Philippines. It is not “money” in our sense of the word. Large pieces were highly prized valuables, each piece having its own history of previous owners and possessed only by high chiefs. Small pieces functioned as currency and could be used as units of exchange for other items of manufacture or for food. Today, all types of pieces are classed as valuables, necessary for ceremonial exchanges which take place at marriage, the birth of a first child and death, while American money (also called udoud) is used for purchases of commodities.

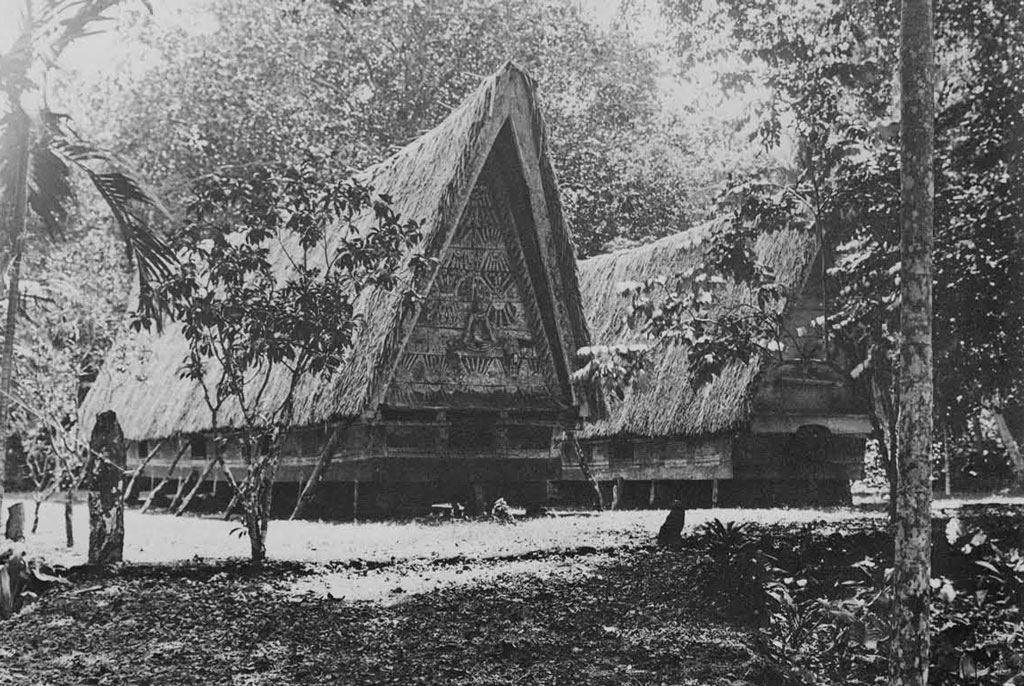

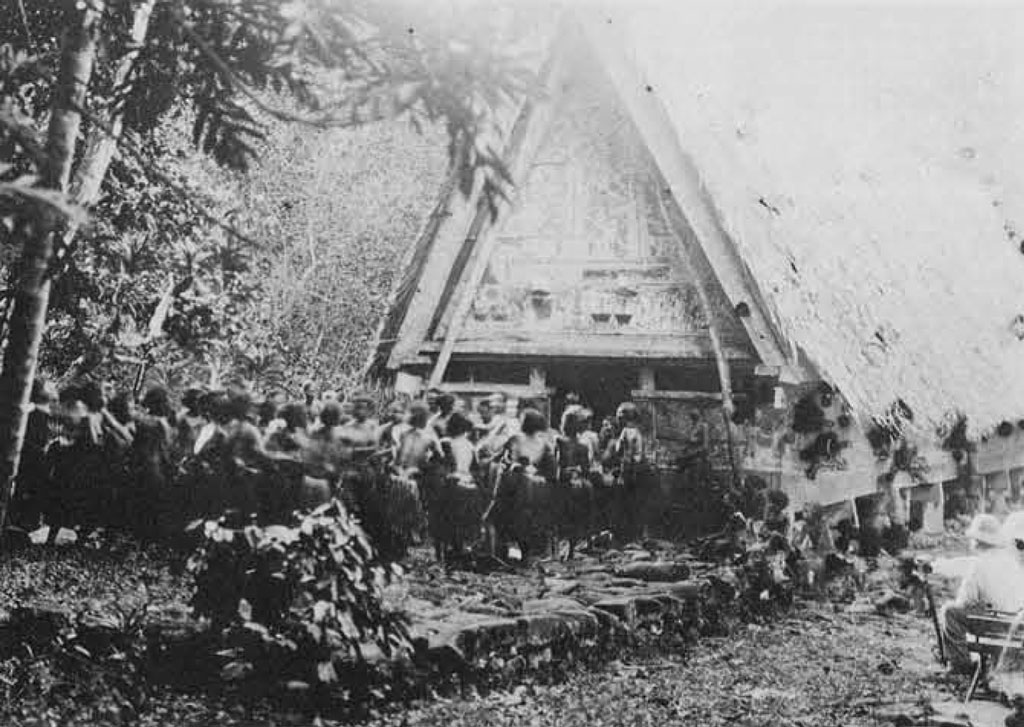

The desire to obtain Palauan currency was a major motivating reason for warfare, and this currency was the source of prestige for an individual, his clan and his community. Men’s clubs, housed in the bai, formed a ready source of labor upon which a high chief could call for both warfare and community construction projects. The number of bai in a village reflected its power, prestige and wealth since a bai was purchased and not constructed by its own members. A bai was usually prefabricated by the builders and then moved to the site of the purchasing village. Being able to afford to pay for the construction of an elaborate bai showed the club was successful in warfare and in amassing Palauan currency, the two major preoccupations of men. An important village would have from three to six bai.

Clubs were ranked within a village, and seating within a bai was also by rank. Males were recruited into a club in early childhood, and the bai was the center for a man’s activities throughout his lifetime.

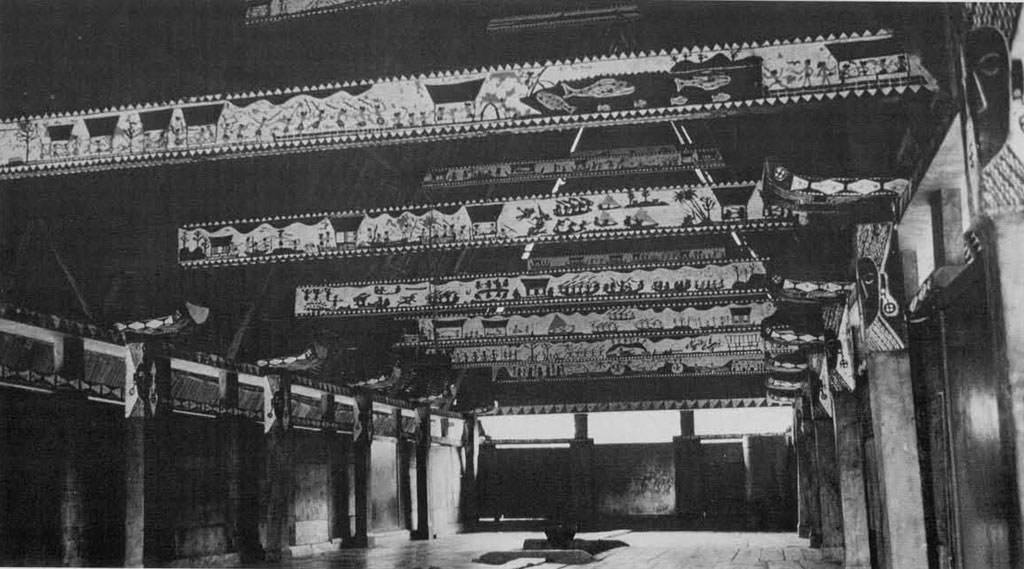

While men’s club houses are common throughout Micronesia, the Palauan bai is distinct in that architecturally it is the most elaborate. The way in which interior tie beams and exterior gables combine decorative and symbolic art with functional architecture so that the whole bai structure is to be viewed as a single entity in perspective, with no one decorative element standing apart, is unique to Palau. The complex series of joints which hold the bai together without nails, pegs or screws is a technique utilized in Indonesia. However, builders in Malaysia-Indonesia have long had iron tools while the Palau bai was accomplished with only stone and shell tools. One of the standing bai, the Bai ra Ngesechal ar Cherchar of the Palau Museum, is 54′ long and 15′ wide, with six doors and partial walls to permit light and air to enter. The interior is one large expanse of wood, broken only by two center fireplaces. Such a large expanse of uncluttered floor is also typical of the Palauan house.

Paints used in decorating the bai were made by mixing lime, soot and ochre with oil from the parinarium nut, producing soft earth shades of white, black, red and yellow. Decorative elements fall into two categories: (1) designs, both symbolic and stylized, found on both the exterior and interior of the bai, and (2) the pictographic art on the exterior gables and interior tie beams which are mnemonic devices to recall legends. Both decorative elements have influenced the modern storyboard, so it is necessary to discuss bai decorations before we can understand the boards.

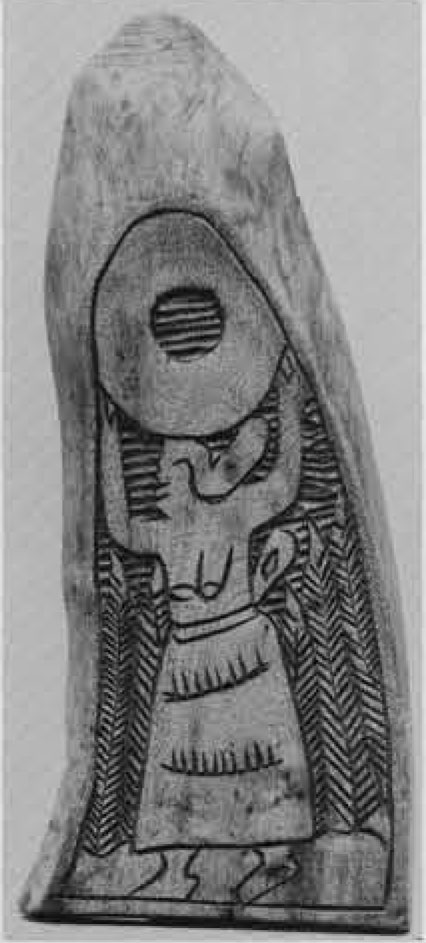

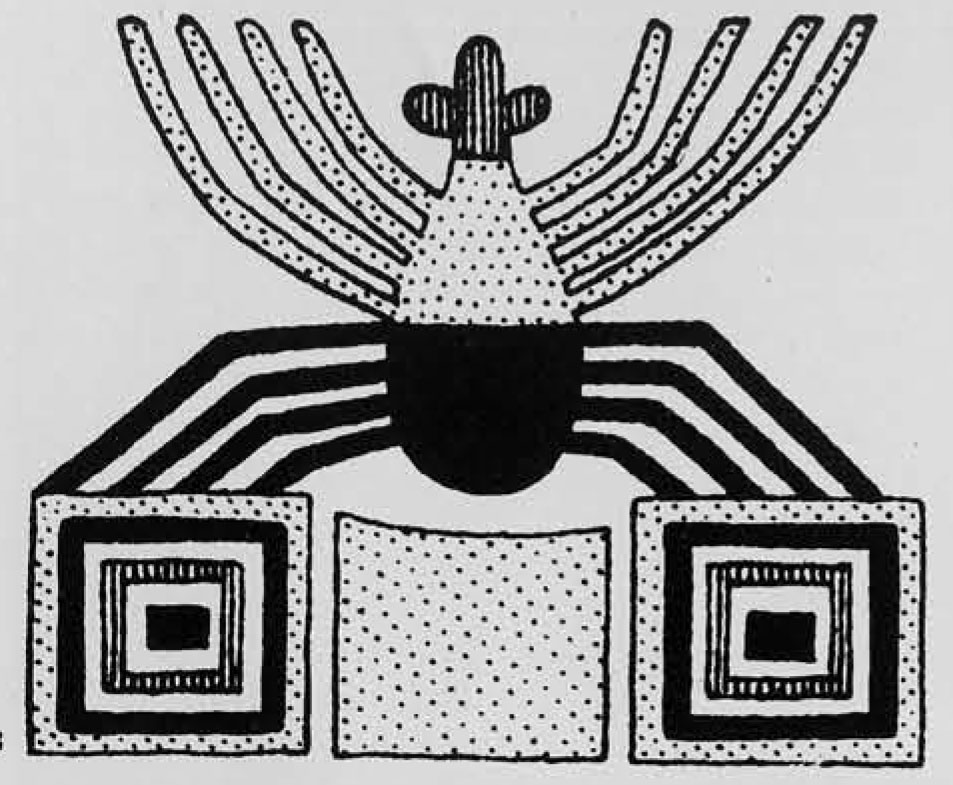

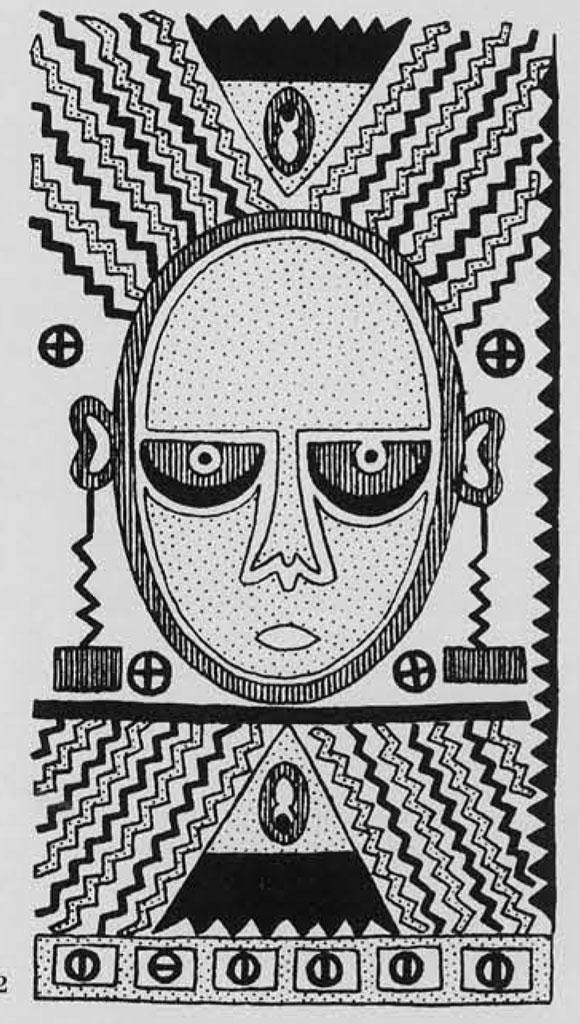

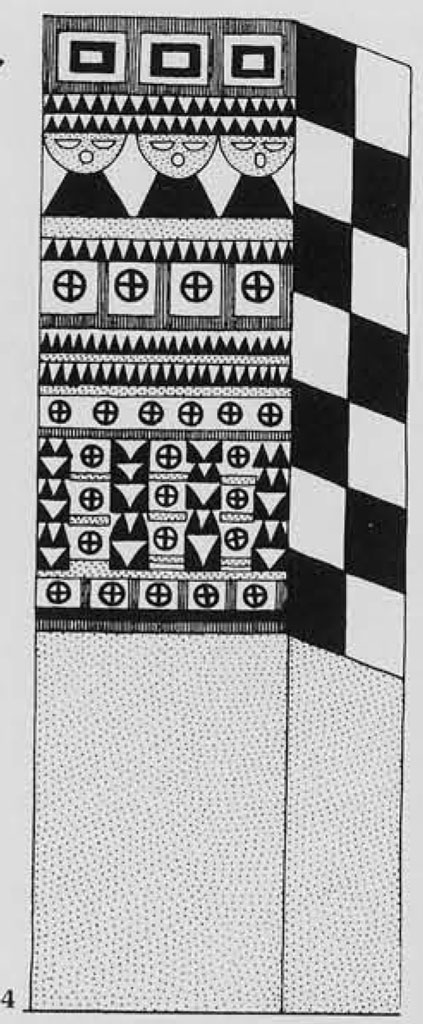

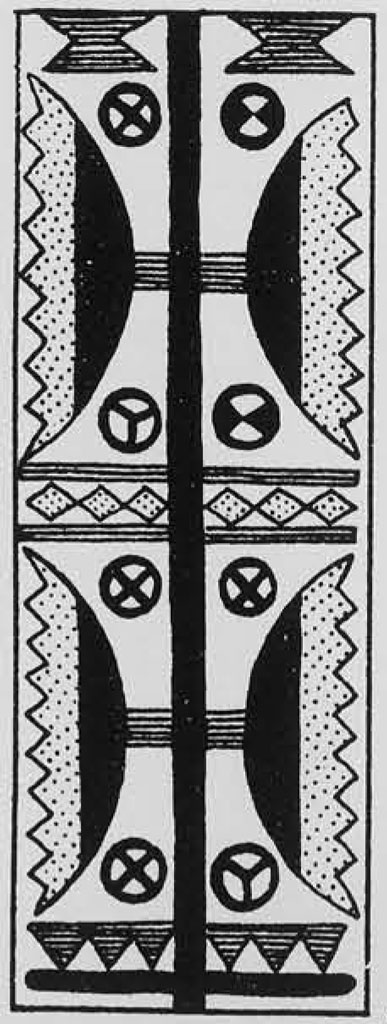

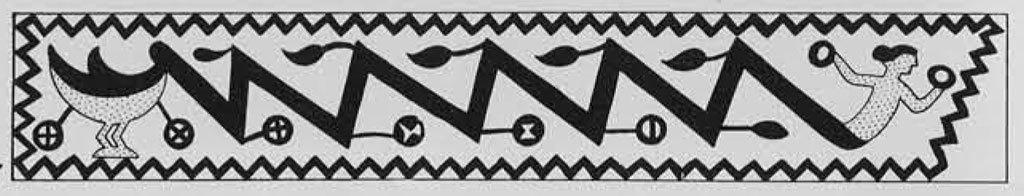

The symbols utilized on bai are limited in number, and where symbols may be used is standardized by tradition. There is some variation to be seen in which symbol was selected to be placed in a specific location. Symbols most frequently seen on bai are: (1) the rooster, a male symbol and an important figure in the legend of the building of the first bai by the gods; (2) the Palauan currency symbol (udoud); (3) the clam (Tridacna gigas,orkim)symbol, which also appears in various forms as a border design (the clam was a source of food and of materials); (4) a demigod with earrings containing the currency symbol, usually located at the top of thebai;(5) a bird (deleroch) who is credited with bringing their currency to Palau; and (6) a spider, symbol of Mingidabrutkoel, a demigod who taught Palauan women natural childbirth (before Mingidabrutkoel, infants were delivered by Caesarian section). These symbols occur on both exterior and interior posts, as border designs along the partial walls, and with less frequency on the interior rafters.

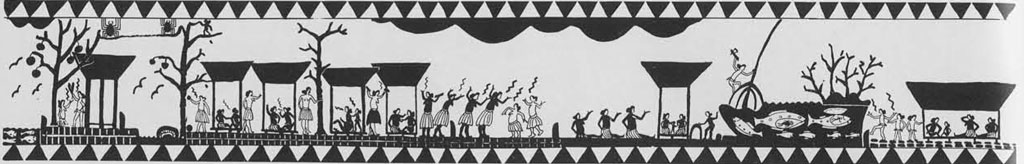

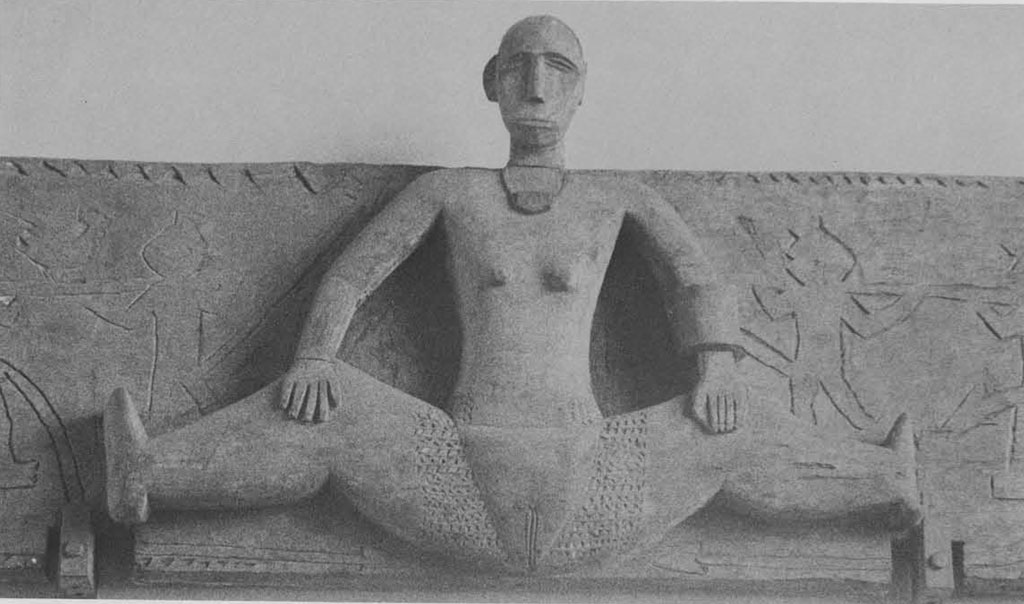

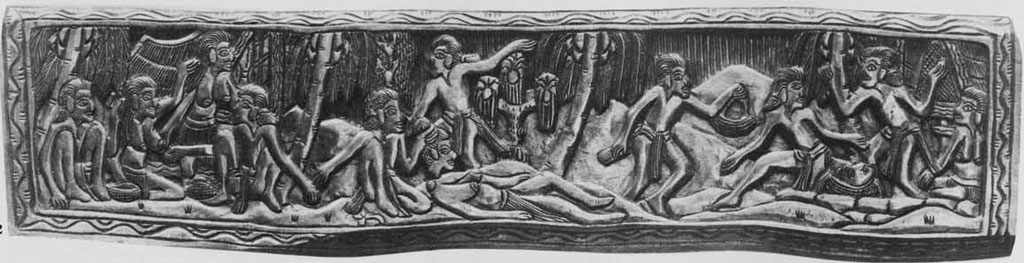

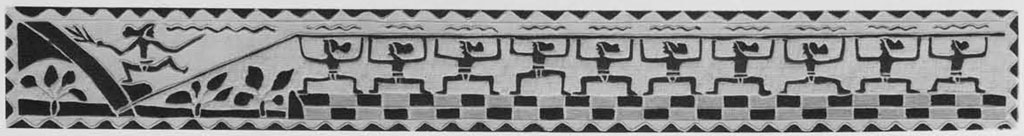

The gables and interior tie beams were artistic mnemonic devices to recall myths or events important to a local club or village. Each beam was approximately fifteen feet long and a foot wide, telling a complete story on one side. There were approximately eight beams in a bai, and many beams were decorated on both sides. From six to twenty scenes might be depicted in a composition, thus permitting a pleasing repetition of the common motifs of people, houses, canoes and trees, with zigzag lines representing speech. The length of the beam permitted the scenes to convey a strong feeling of action and movement. Stories were intended to influence behavior—some might stress punishment while others show the rewards that come from bravery or good conduct. As the legends were known only to certain chiefs and elders, they selected the stories. The selection of stories to be depicted and of symbols to be used was considered by Palauans to be the most creative aspect in bai decoration since the gables and beams were visual statements of the values, histories, exploits and virtues of a particular club or village. The stories having been selected, boards were sketched by a master artist and then delegated to other workmen to be incised and painted.

While the bai is Palau’s most impressive architecture, skills in producing items of wood, shell and tortoise shell were highly developed. Spirit shrines were built as miniature bai, complete with thatch. Houses were of the same sturdy plank construction as the bai. While somewhat plain in appearance and frequently using woven pandanus walls rather than wood, the houses of important people had their exterior gable boards carved and decorated with shapes of the diamond, sun, clam shell (kim) or the currency bird (deleroch). The size of the house and the number of doors a house could have were determined by the owner’s wealth and rank. Elaborately carved and inlaid tables to protect taro (another form of wealth) from rats, carved wooden dishes and containers, tortoise, wood or shell objects of adornment, pottery lamps with figurines, and carved currency jars, all could be purchased from skilled craftsmen. In fact, one never built his own house or canoe, because that would result in a loss of prestige; rather, all manufactured items were bought, and their possession reflected the owner’s wealth and rank. People from low clans did not have the right to own such items or to have a house with many doors.

Within the past century, Palau has completely emerged from isolation into full participation in the modern world. Since 1885, Palau has been administered, in turn, by the Spanish, Germans, Japanese and Americans. Warfare and club life were weakened with each change in administration. Spanish and German missionaries eliminated the practice of women serving as sexual companions (in exchange for Palauan currency) in the bai. Germany sent scientific expeditions to Palau, but in their zest for collecting and with the intention of destroying club life, they cut beams from bai, or dismantled entire bai, to be sent to museums. The Japanese administration (1914-44) had the most lasting effect on Palauan life, remolding every aspect of Palauan culture for participation in a modern world and economy. In an effort to increase exports to Japan, their administration sought ways of developing “authentic” Palauan handicrafts which could be sold to Japanese tourists and as exportable art.

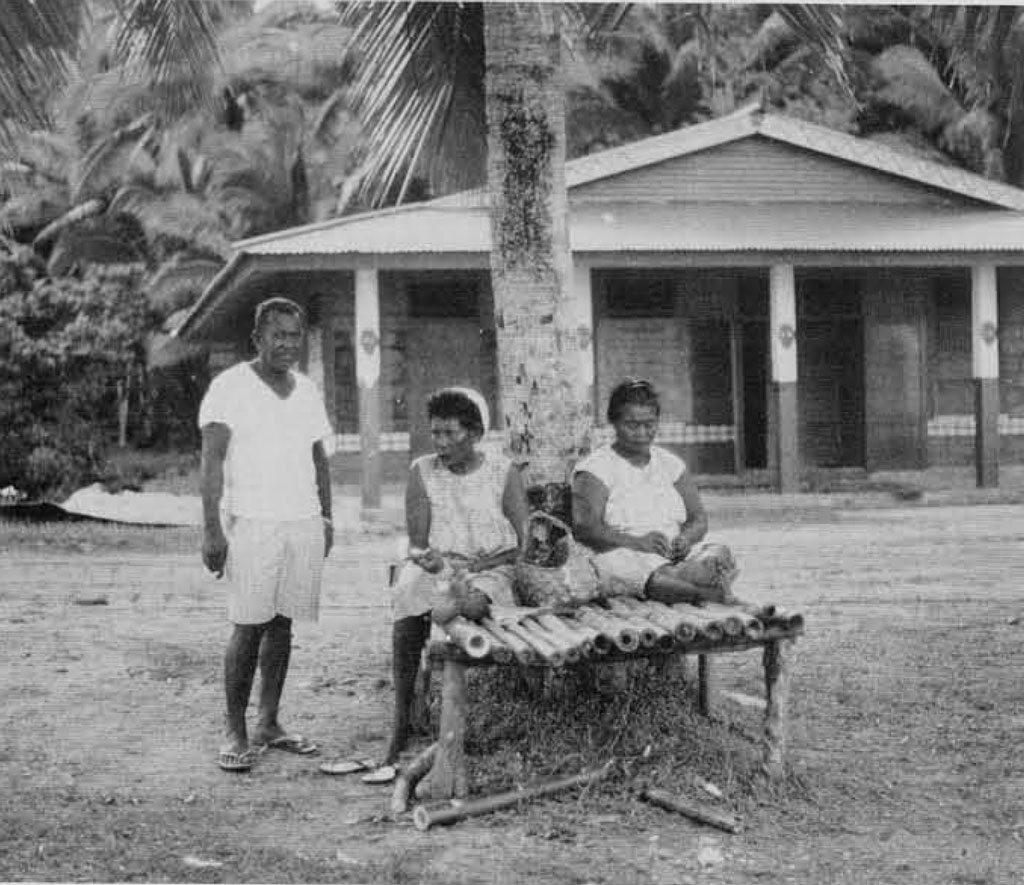

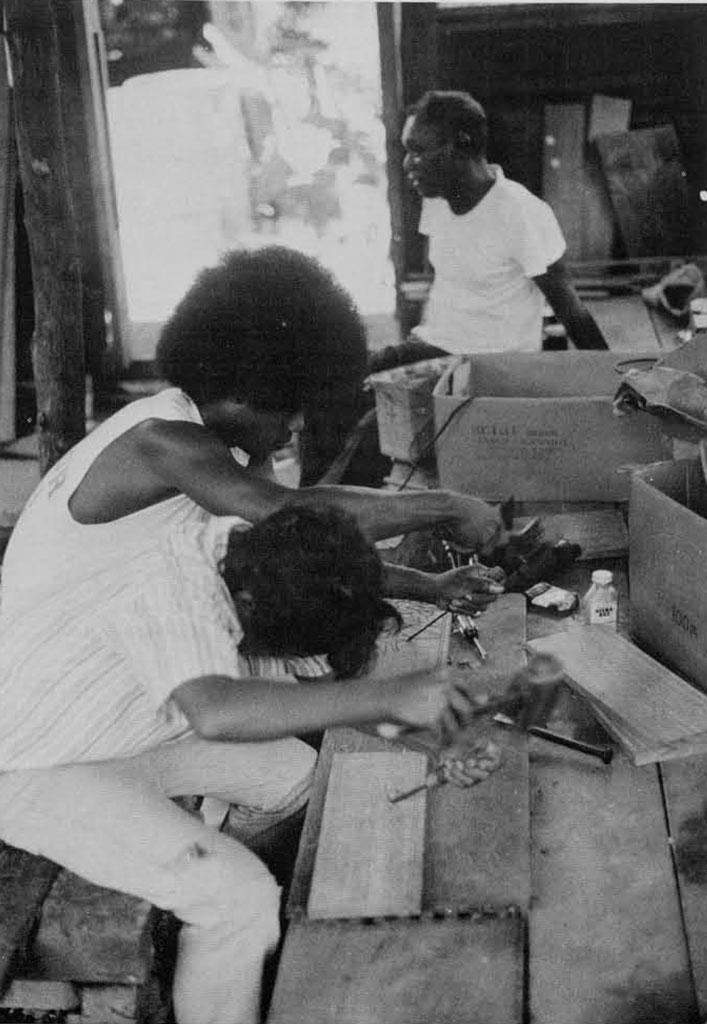

The transition from a story depicted on a bai beam or gable to a small portable board for export came about during this period. This innovation can be traced to one individual, Hisataku Hijikata, a Japanese artist and folklorist who came to Palau in the 1930’s to study art and culture. Older carvers still remember Hijikata and credit him with “teaching us how to make the board small.” One student of Hijikata recalled how his teacher held classes in villages on Babelthuap Island and in the district center of Koror. Hijikata, well accepted by Palauans, requested the elders to sketch stories. He then took these sketches to his students and told them to copy them on wood, making one copy per day until they had mastered their technique. Legends and myths were thereby moved from the realm of private knowledge into the public marketplace. This master artist was regarded as a purist, insisting that his students adhere strictly to the simple lines and colors of the beams and gables. It is reported that boards produced under his direction were difficult to distinguish from the original beams. Hijikata taught his students only approximately twenty of the several hundred stories depicted on beams, and many carvers are still reluctant to do boards other than those they learned from him.

The greatest changes in style and quality of storyboards came in the period following World War II. The American administration recognized the commercial potential of storyboards and encouraged their production. Then, as now, demand exceeded supply, and there was a proliferation of carvers of varying abilities.

The Japanese are said to have preferred painted storyboards. After the war, painted boards began to be done in glossy commercial paints (with the addition of blue and green to the traditional colors). When it was observed that Americans preferred deeply carved unpainted boards, this type of board became the major type to be produced. To add visual interest to the unpainted boards, backgrounds became more pronounced. Carvers experimented with various styles of depicting stories, settling on those styles which sold the best. In interviews with carvers, I learned that the motivating reasons for the changes that have come about since the war were always to accommodate style and content to the market, to make whatever sells best.

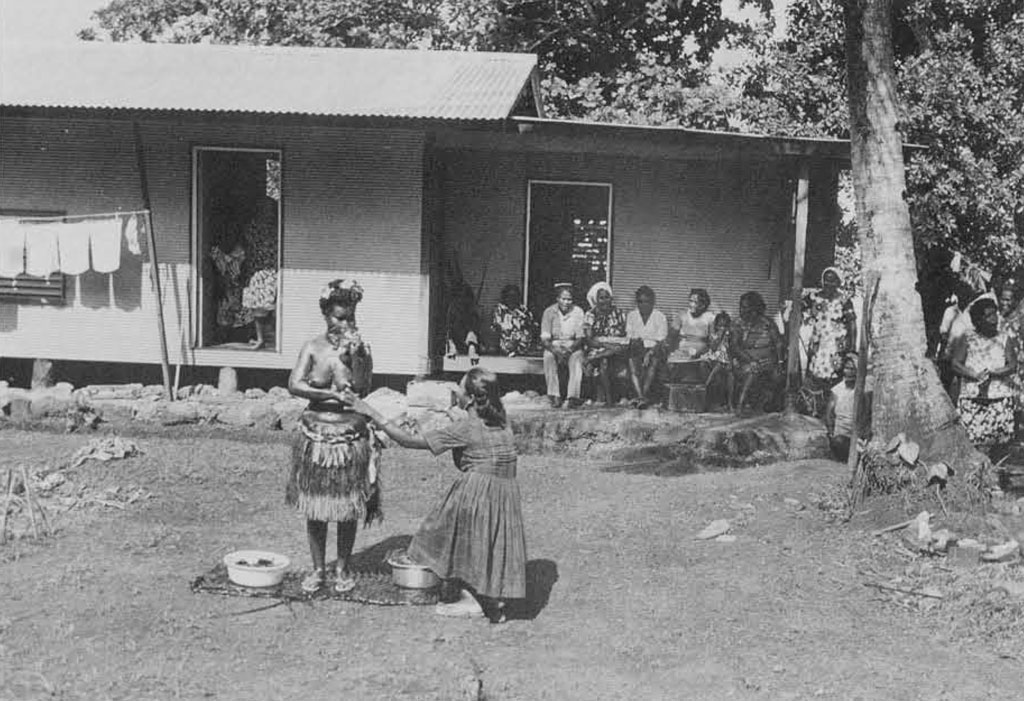

The district center of Koror today is “urban Oceania,” a jumble of iron and wooden houses and shops built in “Japanese style” or “American style,” crowded together in a town that continues to grow too rapidly as people leave the more traditional outer islands for the city. While all communities still have a public building called a bai, these are generally a simple rectangular structure of sheet iron or concrete, used for meetings or public gatherings. In 1969, the Palau Museum constructed a bai on its grounds because it was feared knowledge of this traditional architecture would soon disappear. However, Palau is changing rapidly, as it has over the past century, and there is now a growing interest among Palauans in their traditions and history. By the summer of 1974, a community on southern Babelthuap had completed an old-style bai which they say is to be used in the traditional way: “rubak (elders) will sit inside and talk; young men can sit and listen outside; mechas (women) can dance inside.” More “modern” Palauans suspect the community plans to charge tourists to photograph their bai.

jets now bring visitors from Guam, and there is an air-conditioned American resort hotel to accommodate them. Japanese and American tourists come planning to buy a storyboard, and carvers are harassed by tourists who want boards on demand. When Koror is crowded with visitors, all boards are sold and people will cajole or bribe carvers to produce a board. Some carvers have instructed taxi drivers not to tell tourists where they live, preferring to leave boards at the hotel giftshop or to ship them to outlets in Guam or Kwajalein. One of the places most likely to have boards available is the jail, where inmates have turned the carving of storyboards into a profitable business. The boards at the jail frequently emphasize the sexual aspects of old beams and legends to such an extent that they are called “porno boards.”

In a situation where even bad boards can easily be sold, there is a wide range of talents among carvers, some of whom were students of Hijikata and regard themselves as “artists” in the Western sense, while others are not adept with a chisel and are simply trying to earn easy money. There is a small group of carvers who do not participate in the tourist trade but carve bowls or tables for other Palauans. While a skilled carver can produce both painted and natural boards, many young carvers say that paints are too much trouble. A board for the tourist trade can be produced in a few hours since it is axiomatic that carving for an outsider does not require the same care as for a friend or relative.

Price is determined by the square inch rather than by the space required in which to depict or represent a story. Perhaps for this reason, while carvers maintain they can carve any story, only a few themes repetitively appear on boards (although a different story might have been requested)—the breadfruit legend, the history of Yapese coming to Palau to mine limestone for their currency, the story of two ill-fated lovers (Surech and Dulei), and several versions of legends of deceived husbands. Not all legends can easily be compressed into a small board. A board made for the Museum in the “old style” by the master artist who sketched the Palau Museum bai beams depicts an upturned canoe in a taro swamp, and this can suggest two different stories.

It is interesting to note that the boards most commonly produced for the tourist trade are of stories which can be represented by a single symbol. If one sees an upturned shark (a sign of trouble at home to the fisherman], he knows it is one of the “deceived husband” stories. The doughnut-shaped disk is the requisite symbol for the Yapese currency legend, no matter what the size of the board. Fish coming through a tree trunk signify the breadfruit story. Most hoards contain a representation of their origin, the bai, usually decorated with the currency demigod or with the Palauan currency symbol. If a very small hoard is requested, only the symbol can be used to suggest the story; a large board permits the carver to depict the central action of the story and the number of scenes can be further expanded to suit the size of the board. However, none of the modern storyboards actually depict a story in the traditional manner of the bai beams.

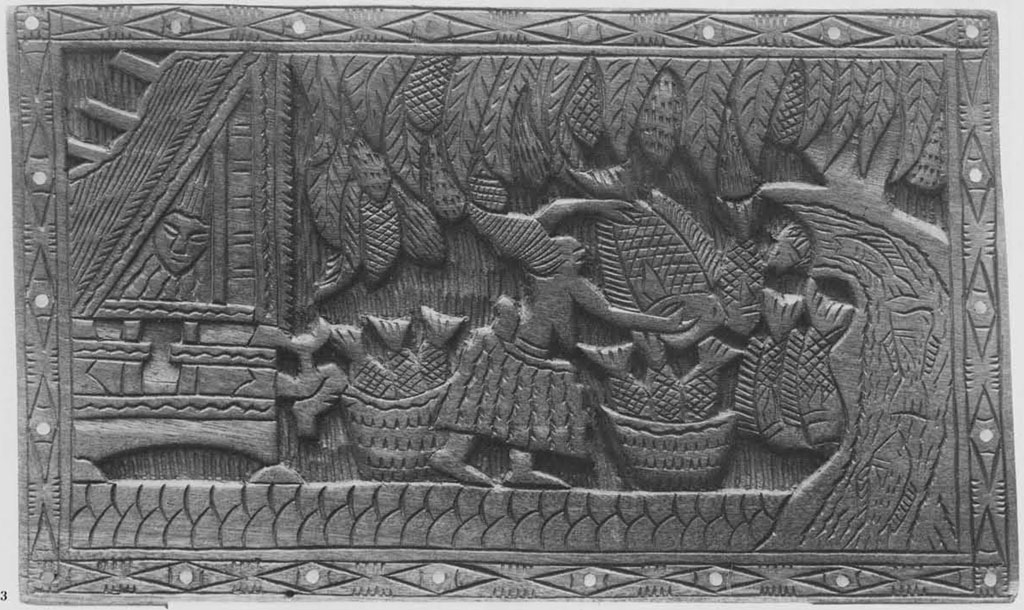

Surech and Dulei (in the old style). Dulei, a young man from Ngkeklau, fell in love with the very beautiful Surech of Ngiwal (the locations of the villages vary). Because the two villages were frequently at war, Surech and Dulei met secretly in the jungle between Ngiwal and Ngkeklau. Word of their love for each other psread throughout Palau, and Mad, high chief of Ngarard, heard of the affair and of Surech’s beauty. He summoned Dulei, and since Ngkeklau was a satellite of Ngarard, Dulei had to appear before Mad. Mad instructed Dulei to bring Surech to him, saying that he wished to look upon the face of this beautiful girl. Dulei suspected Mad’s intentions but he knew he must comply with the chief’s demand. He took his hatchet with him to meet Surech in their secret place. There he told Surech of the chief’s request and what he must do – cut off her head. Surech wove a basket which would just fit over her head, then lay down, bidding Dulei to do what he must. She first sang a song of her love for Dulei. Dulei cut off her head and took it in the basket to Mad, saying he had brought Mad what he had requested – teh face of Surech. Mad was horrified and bid the villagers to kill Dulei. Some people say Dulei misunderstood the chief’s orders and intentions while others say Dulei knew the chief would take Surech for his own. Both interpretations teach obedience to a chief’s commands.

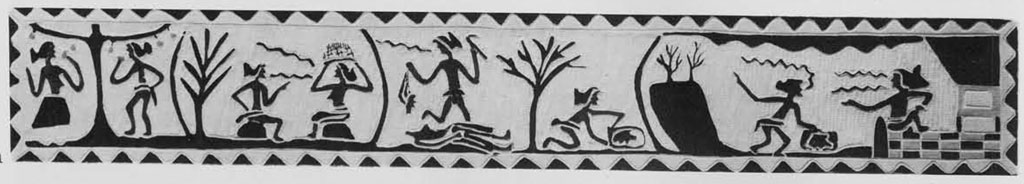

In the board, we see (1) Surech and Dulei eating in the jungle; (2) Surech fitting the basket over her head; (3) Dulei holding the decapitated head and then placing it in the basket; (4) Dulei presenting the head to Mad. This “old-style” board is painted in the traditional colors with a soft earth finish. Carving is shallow, and backgrounds are plain and painted white to permit the figures and actions to stand out.

The use of symbols on boards is an element borrowed from the design elements of the bai. While carvers are still experimenting with styles other than those taught by Hijikata, the techniques they turn to are often drawn from tradition. Inlay, a decorative element in other traditional carved objects, is now used in storyboard borders and faces. Bowls were decorated with carvings in the round, and the workers in the jail are experimenting with producing “stories in the round.” Some carvers are producing boards with the old style of shallow incising in response to the tourist demand for boards like those seen on the beams of the Palau Museum bai.

That storyboards are a link between life as depicted on bai beams and modern life can he seen in the following sequence. The beam in the foreground of the photograph of the interior of the Palau Museum bai depicts the story of Mingidabrutkoel, who taught Palauan women how to deliver children naturally rather than by Caesarean section, and it shows the ritual steamings (mesuroch) and public presentation of the new mother (ngasech) which take place at the birth of a first child. The same legend is still depicted in a modern storyboard by a student of Hijikata. The public presentation of the new mother (ngasech), seen at the left of the storyboard, is a custom which died out under the Japanese but which has been revived by young Palauans, now frequently college students, who are finding renewed pride in Palauan traditions. Ngasech are now held each weekend for young mothers who have undergone the ritual baths and steaming (mosuroch).

Because storyboards of varying workmanship are produced for the tourist trade, it has been suggested by some critics that all such items be considered merely “airport art” and not an “art form.” Such a view of the storyboard ignores the history and function of this art form in Palauan culture. It will be recalled that the board’s parent, the boi, was not intended solely as an aesthetically pleasing structure. and that the major creativity in bai decorations was in the selection of the story to he depicted. Instead, the bai served as a visual statement of the wealth and prestige of a club and community. The wealth complex is still Functioning quite strongly in Palauan social organization, and most of one’s efforts are devoted to acquiring Palauan currency and American money for one’s kinsmen. It does not seem strange to me that the profit motive should be so firmly combined with Palauan carving today. These visual statements of another way of viewing the world would not have survived without the profit motive.

The long debate whether New Guinea masks or African carvings might be considered “art” has brought into focus two different ways of viewing art—the approach of anthropologists, who examine an item’s function and place within a specific culture. and the approach of art critics, who react to the aesthetics of an isolated item stripped from its context and symbolic meaning within that culture. Palauan storyboards—popular items created simply for profit but based upon a traditional art form—again raise the questions of “what is art?” and “who decides what is ‘art,’ ‘primitive art’ or ‘airport art’?”

The Breadfruit Tree (Ngibtal). The female demigoddess, Milad, taught Palauans how to grow taro. In return, when she settled on Ngibtal Island (between Melekeok and Ngiwal), she was rewarded by the gods with a breadfruit tree which yielded fish through its branches, thus assuring the old woman of a steady supply of food. The villagers grew jealous of the woman and chopped down the magical tree. The ocean came up through the hollow branches and drowned all the villagers except Milad. The sunken island can still be seen below the water.

This story is part of a much longer epic. The modern storyboard always shows the fish passing up through the trunk of the tree, a technique attributed by carvers to Hijikata. However, this same story utilizing the cut-away technique on the breadfruit tree is depicted on the exterior gables of a bai now in the Berlin Museum.

The carver of this board has used shell-inlay to deocrate the borders, a decoration traditionally used in other types of carved objects but not bai beams or gables.

Board in the style of the Bai. Not all stories can be successfully reduced to a single symbol or a moderate sized obard. The upturned canoe is the usual symbol for the story of Tebang, a son who rebelled against the control of his parents and left home. In a neighboring village club Tebang gained enough prestige and wealth to have a canoe made. The canoe was built in the mountains and in moving it down to the ocean, it became stuck in a taro swamp. Tebang had to call upon his father, an expert in magic, to say magical pronouncements to dislodge the canoe. Tebang relaized the value of parental love and, with his apology, was welcomed back to his family.

The same symbol can also suggest Ngeleket Budel and Ngeleket Chelsel (“outside child” and “inside child”). An adopted child was given poorer food than the natural child of the adoptive parents. The adopted child remained with them until he was grown. He then asked his father to build him a canoe. The fatehr did, and in move the canoe from the mountains to the ocean, it became stuck in a taro swamp. The adopted son said the magical words which made the canoe fly into the water. The boy then left, ending the parent-child relationship with a curse that the adoptive family will have beautiful women but they will be plagued by misfortune and greedy for food. This story teaches woman not to mistreat adopted children.

Yap Currency Theme (Balang ra Rebeluulechab). The Yapese came to Palau to mine the limestone for their currency and transported the huge disks a distance of some 250 miles by canoe to Yap. Several thousand pieces of the currency, some as large as 12 feet in diameter, remain in Yap, and pieces of incompletely mined limestone can be seen today in caves near Koror. Most mining occured during the middle of the late 19th century, after European contact.

Storyboards use the doughnut-shaped disk as the requiste symbol, and some show decapitated heads to suggest the bloody era in Palauan history during which mining took place. There are two popular storyboard versions of this theme, one showing the canoes en route between Palau (represented by a bai) and Yap (represented by Yapese men’s house); the second type of board depicts a group of Yapese pointing to a full moon, the inspiration for the shape of their currency.