No matter how far the town, there is another beyond it.”

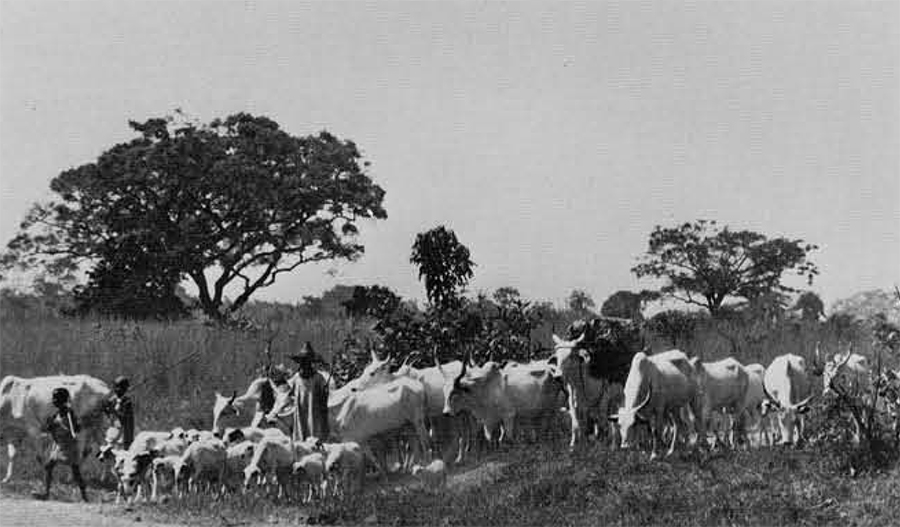

Little affected by western ideas and technology that are fast changing the traditional life of most African ethnic groups, the Nigerian cattle people of the north have stubbornly kept to their seasonal migrations as they have done for untold centuries. Pastoral nomads known under the general name of Fulani are found in a narrow belt that stretches south of the Sahel, from Senegal to the Sudan. At the onset of the dry season, they drive their cattle from the arid pastures up north to wetter areas farther south where grassland, fallow fields and surface water provide suitable grazing for their stock. Although a minority group, the nomad Fulani integrated neither socially nor politically with other ethnic groups. Other Fulani, however, settled permanently in the cities where they attained a position of great influence and of such importance that they became the accepted rulers of several emirates previously under the jurisdiction of Hausa families.

Not only can the Fulani be distinguished from other Nigerian people by their way of life but also by striking physical differences. Although dark-skinned, their anatomy is clearly not negroid. They are usually tall and slender, their oval-shaped face shows a straight, narrow nose quite distinctive from the broad Bantu nose. The way they dress is also very unlike other Nigerian groups.

The origin of the Fulani people is shrouded in mystery. Theories about their relationship to other people are numerous and wide-ranging. They are generally described as “Hamites” of nilotic origin, which would explain the possession of longhorned cattle. Their language, however, is related to that of people from coastal Senegal, the land of the Wolof and the Serer, a thousand miles away from the Nile. East or West? Several romantic suggestions have been put forward: for instance, their relationship to Phoenician crews left behind in coastal settlements during Pharaoh Necho’s expedition that sailed around Africa in the 7th century B.C. Another fanciful hypothesis claims their relation to the Malaysian seafarers who landed along the eastern shores of Africa before settling in the island of Madagascar. Generally well accepted is the suggestion that they migrated from the Nilo-Sudanese areas at a time coinciding with the expulsion from Egypt in 1570 B.C. of the Hyksos, pastoral kings of Asiatic origin. Those who support the theory of western origin postulate that the Fulani lived in the region of the Tekrur where they are still known under the name of “Tukuror,” and that at one time they lived in close association with Berber pastoralists who visited the Senegal Valley seasonally with their cattle herds. The intermarriage between Phoenician colonists from Syria and Sudanese Uragara of Berber origin in the region of Fezzan has also been suggested. Tradition has it that the Fulani “speak the maternal language but not the language of their father.”

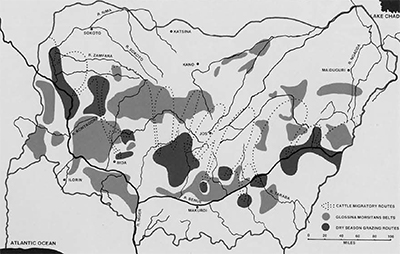

At present, an estimated seven million Fulani are dispersed over a distance of some 4,500 km., from the Atlantic Ocean to Lake Chad, within the grassland savannahs south of the Sahel and north of the main tsetse fly belts, half their numbers located in northern Nigeria. The occupation by the Fulani of this vast territory was not only of great historical importance but also acted as a catalyst to the rapid diffusion of the Muslim faith in western Africa during the 18th century. At that time, the “city Fulani” attained strong positions in most Hausa towns of northern Nigeria. Their prestige and leadership became firmly established when their chief, Usman dan Fodio, organized and waged a religious war (jidah) which, while definitely implanting the Islamic religion in that part of Africa, at the same time brought several emirates of Sokoto, Kano, Zaria and Katsina within a single Fulani empire that also included large areas previously occupied by the Nupe people, and extensions reaching the Cameroun border. This empire governed by the Sultan of Sokoto, Usman dan Fodio, was to remain unchallenged until the end of the 19th century when it became part of the British Crown Colony of Nigeria. Thanks to the proposals of Sir Frederick Lugard (considered the “founder” of Nigeria) of government through indirect rule, individual emirates were maintained if not with their previous independent power, at least within the bounds of traditional functions. But the introduction during colonial times of western ideas, techniques and religion was to have a profound effect on the traditional life of most Nigerian people. The later rapid development of the country, however, was to make far less change in the way of life of the Fulani who kept to their pastoral traditions ruled by the eternal rhythm of the seasons and care of the herd.

The onset of the dry season in Nigeria, due during the second half of October, is usually sudden, often well marked and mostly on time, It is then that the nomadic Fulani gather their livestock to start their slow migration south, leaving the care of the village to the elders. The seasonal journey to the south in response to shortage of water and good pasture on the home range is possible only because during the dry season tsetse flies have abandoned most of the open wood-and grassland to concentrate in restricted wetter habitats. The return of the Fulani to their northern “base camps” during the wet season is imperative, firstly to avoid exposure of the herds to trypanosome-disease-carrying tsetse flies which re-occupy during that season most of the savannah land, secondly because of the start of the planting season in the fields that would restrict cattle movement and pasture.

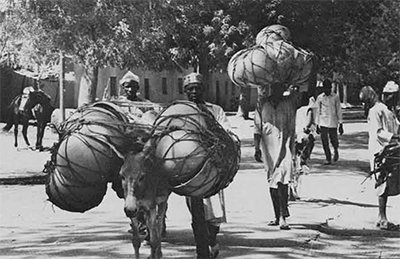

Migratory groups are usually composed of 10 to 20 families each possessing 20 to 40 head of cattle; they travel an average distance from base camp of about 180 miles. If the pace of travel southwards is usually a leisurely one with stops at favorable places, the return to the north at the start of the rains is often more precipitate so as to avoid the crossing of swollen rivers and waterlogged swamps. In the course of the five to six months’ journey, temporary camps are established usually near a pagan village. Provisional shelters are built by the women from a frame of bamboo or other lightweight wood that is carried on the back of one of the bulls, together with some basic kitchen utensils. Arriving at a suitable campsite, the frame is set up covered with grasses or leaves except for a small door opening on the west side, where the herd is traditionally kept in a fallow field with waste vegetation from the last harvest. It is customary to light a fire from twigs of “geloki” (Guiero senegolensis) which helps to keep the flies away. The occupation of such pasture is usually with the assent of the owner who values the manure that accumulates on his field and who sometimes pays with money or barter for the privilege of keeping the cattle on his land. A major problem for the Fulani herder is to find reasonably tsetse-free water courses—daily care of the herd may last well into the evening.

While in camp, the Fulani women are responsible for the milking of the cows and for the processing of various dairy products. Profits from the sale of these products at the local market are used by the women to run the household. The care of the livestock, all belonging to the husband except for a few cattle owned by the wife and derived from an original gift from her father at the birth of her first child, is the responsibility of the men who also pay the per head government tax. The number of cattle owned by each taxpayer is established during a yearly census carried out by a government official. The evasion of taxation is one of the major concerns of the Fulani husband. Great dexterity and imagination are exerted to achieve this goal, the whole matter being accepted by both sides as a test of wits displayed with great determination and ingenuity. One of the methods is to add a number of one’s cattle to the herd of a friend-conspirator that has already been counted; another, to hide part of the herd in a dense, little visited patch of forest. Although he may not know the exact number of animals in his herd, the Fulani recognizes each individual by a given name that describes external characteristics of hide color and pattern, shape and size of horns and the animal’s pedigree. His knowledge often extends to that of the herd of his neighbors.

The non-nomadic or city Fulani also possess cattle but these are herded by hired hands at pastures in the vicinity of the town. While cows of the nomadic Fulani are milked exclusively by women, those owned by the city-dwelling Fulani are milked by men.

Besides a yearly migration, certain Fulani groups are known to have undertaken long-distance and permanent moves. These may take several years to accomplish. One such permanent migration started in 1932 from Jos and ended in Adamawa near the Cameroun border, 600 km. away, where it arrived in 1935. The reason for such a break-away migration must be sought in the independent character of the Fulani who do not accept intervention in their affairs or tolerate directives from local authorities. Another reason is the search for better pastures and conditions for their livestock.

The Fulani family depends for its subsistence upon its herd, whose health and effective increase is subject to the care and pastoral skill of the family. Cattle are a prized possession and capital investment, sold only to meet the need for cash on occasions of extraordinary expenses and payment of taxes. Slaughter for meat is done only on ceremonial and ritual occasions.

Fulani families are grouped into agnatic lineage clans established as a result of a system of preferred cousin marriages. The clan has a leader selected by acclamation based upon patrilineal descent, age and prosperity. Marriage between nomadic and settled Fulani is rare, even more rare between Fulani and non-Fulani. An exception is that in northeast Nigeria the long co-existence of Fulani with Kanuri has fostered intermarriage between Fulani men and Kanuri women but very seldom between Fulani women and Kanuri men.

Betrothal arrangements between children when still young are customary. At marriage age, as early as 17 for the boy, 14 for the girl, the arrangement, if confirmed by both parties, is sealed by the gift of a bull from the boy’s father to the girl’s father, the animal being slaughtered and eaten. Other gifts follow at the occasion of festivals. The marriage is concluded by simple request of the boy’s parents, sometimes made more official through the reading from the “fatika” by a learned man or by the camp leader.

To show their strength, self-control and maturity of character, young men participate in a game of “Sara” during which they submit without showing pain to a flogging inflicted by another boy with a specially prepared strong, supple stick. Dances are held at special occasions such as the Muslim Id el Fitr and Id el Kabir, often followed by sexual laxity at night when boys chase girls.

A married couple begin their really independent life when after two years of marriage or at the occasion of the birth of the first child they are given some cattle to start their own herd.

The last three months before the birth of the first child the expectant mother lives in her paternal home, If old traditions are respected, she remains there until the child is weaned, two years for a girl, 21 months for a boy, during which time she is not visited by her husband. After her return to her husband’s house, she receives extra money from him to buy fancy jewelry and clothes.

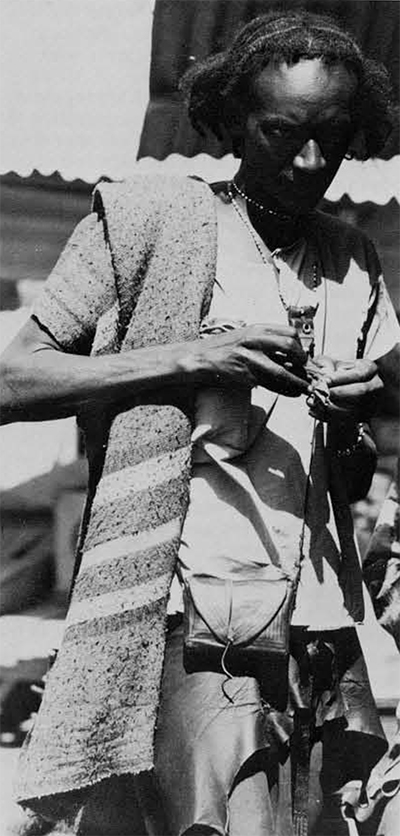

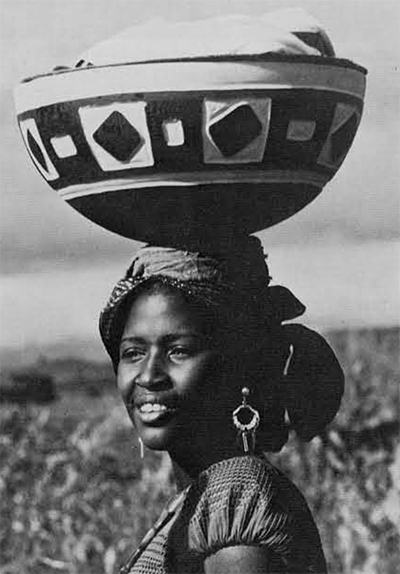

Both women and men attach great care and importance to their appearance. Both like to dress in a fanciful way: the women love bright ornaments, the men like to parade in their finery. A typical Fulani girl’s outfit consists of a short, bright-colored embroidered mid-rif blouse atop a hand-woven wrapper. The Fulani woman is immediately recognized by her plaited hairdo, two little side-tails, elaborately interwoven with brass wire or studded with cowries, projecting forward at each side of the face or bundled together in a single tail at the neck. Earrings, bracelets, bangles, necklaces, anklets and other refineries are profusely displayed. Cosmetics are lavishly used: lipstick, rouge, dark blue eye shadow, nail polish, powder and perfume. Dresses and hairstyle seem to differ between various groups along the migration routes, perhaps according to the clan. Fulani women can be spotted from a distance by the large white or cream-colored calabashes delicately balanced on their heads. Most of these calabashes are beautifully decorated with fire-blackened or carved geometrical designs and covered with a lid of woven straw showing traditional designs by means of colored patterns. Fulani migration routes can be traced by following the markets where the calabashes are for sale.

The number of calabashes, and the proficiency of their decorations, are the pride of the Fulani woman. Her collection is started with gifts from her parents at her wedding and later additions on various occasions. She has the opportunity to show her collection during a yearly festival when she will take out, clean and polish her best calabashes and display them in front of her hut. There is no official winner or prize but the whole community can judge who possesses the finest pieces, and each of the competitors is left with the impression that hers are the best.

Each type of calabash is known by a specific name—its use can sometimes be recognized by its color and decoration. The large water calabashes, for instance, are often stained red by means of an extract from the stems of a certain kind of millet mixed with soda. After the treatment, the calabash is well rubbed with butter to give it a shine and to improve water-holding capacity and crack resistance. Decorations are the work of the Hausa trader carried out according to the individual taste of the buyer at the moment of purchase. Formerly, the designs were traditionally specific for each clan but fashion and individual preferences have displaced tradition, while certain types of designs may not he so much indicative of the clan as of the markets along the migration routes.

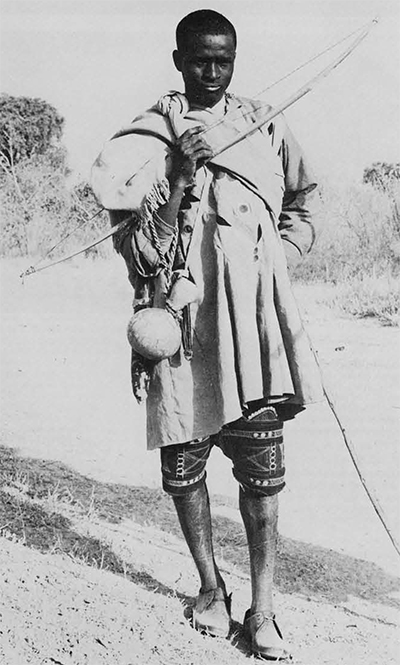

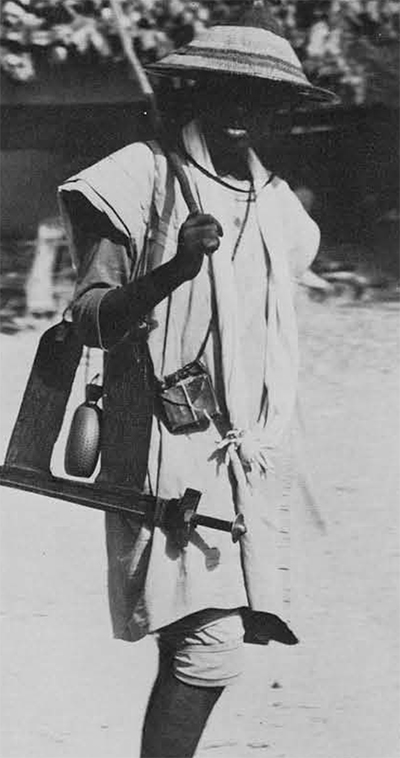

Dressed for “going out,” a Fulani man usually wears a loose, blue, embroidered tunic above applique-decorated breeches tapering to a tight fit at mid-calf, called “wando.” He often wears a conical straw hat, strangely similar to that worn by the Zulu of southern Africa. The “Sunday’s best” outfit is completed by numerous amulets, small pouches made from red-tinted leather and, above all, a dignified sword in a leather scabbard hanging from the shoulder by a broad leather strap. While herding his cattle, however, he may be clad only in ragged shorts worn underneath an apron-shaped leather garment. Identical to other pastoralists, he walks with his arms folded athwart a stick resting on the shoulders behind his neck. At rest, he leans on his stick planted in front, the sole of one foot placed on the inside of the knee of the other leg, a position remindful of the Masai.

The Fulani believe that spirits inhabit large trees such as the tamarind and the baobab, and also live in termite hills. It is said that in the Adamawa region they bury their dead close to a termite hill. To knock down a termite mound is considered a very bad thing to do. They are often associated with fertility and when salt-licks are given to the herd, usually once a month, the salt block is laid upon a low termite mound in the belief that this will increase the production of calves.

The Fulani are friendly people and seem particularly attracted to foreign travellers. The latter may feel a kind of spiritual bond not unlike that which draws together fellow wanderers roaming alien territory.

As long as the Fulani keep their stimuli for moving, and maintain their adoration for cattle, chances are that they will remain an independent ethnic group, happily aloof from a fast changing world from which they are culturally segregated. Closely knit in traditional clans, they have kept their integrity by abstaining from intermarriage with other ethnic groups and by following the nomadic life which is at the origin of their society.