The story of the Pennsylvania-Yale Project at Giza takes us back to the beginning of American archaeological work in Egypt. In December 1902 the Egyptian Government granted concessions for archaeological work at Giza to three universities, one of which was the University of California (the other two were German and Italian). The University of California was represented in the negotiations by Dr. George Andrew Reisner, and he obtained for it the Third Pyramid and part of the area east of the First Pyramid; he would be the field director. Originally the University Museum was to cosponsor the project, but withdrew. In 1904 Dr. Reisner transferred sponsorship of the Giza work to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston although the University Museum continued its interest, and Reisner always maintained friendly relations with the University Museum until his death in Cairo in 1942.

In 1915 part of Giza was excavated by the Eckley B. Coxe, Jr. expedition from the University Museum, of which Clarence S. Fisher was field director. Also, from 1923 to 1925, Alan Rowe, later to be the University Museum field director at Meydum, excavated at Giza under Reisner (see p. 28).

In 1969, David O’Connor and I started the third season of the Pennsylvania-Yale expedition at Abydos (see Abydos article). However, the political situation in Egypt soon resulted in a suspension of work at Abydos and all other sites, except for those in the four major cities of Alexandria, Cairo, Luxor and Aswan. This situation led directly to the resumption of work at Giza, for it coincided, in 1970, with my new position in Boston and the assumption of the responsibilities of my predecessors, including of course the continuation of the publication of the expedition results from Giza. Considerations of funding also played a part, for the records of the Giza excavations, with extensive drafts of chapters by Reisner, were in Boston and the Museum there had established a fund for their publication. On the other hand, the Pennsylvania-Yale grant from the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs of the U.S. Department of State was only half spent on the work in Nubia and Abydos, and this grant would come to an end without continuing projects. With the concurrence of the Directors of the Peabody Museum at Yale and the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania, Dr. O’Connor and I decided that he would excavate at Malkata at Thebes (see pp. 52-53), funded by Smithsonian Institution PL480 grants, and I would conduct field-work at Giza to record the reliefs of the offering chapels of the Old Kingdom, using the Pennsylvania-Yale grant.

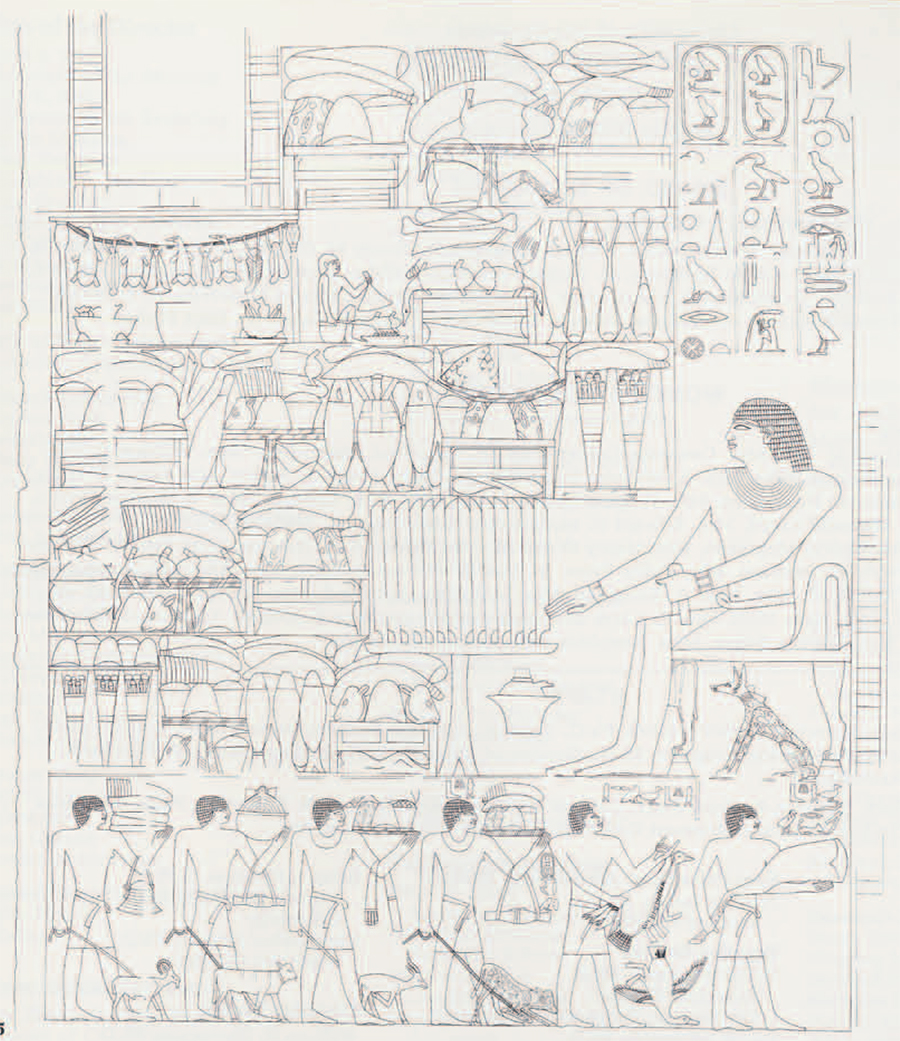

Reisner was a pioneer in this country of statistical analysis, typology and horizontal stratigraphy. At the Giza necropolis his chief concern was the relation of the mastaba tombs to the overall plan, the relative importance of each as determined by the cubic content of its chambers and burial arrangements, and the typology of its construction and burial equipment. For the reliefs of the chapels themselves, his concern was mainly in the type of scenes represented, their distribution over the available wall surfaces, and the identification of the status and family relationships of the owner. Accurate tracings of the scenes were not always attempted or completely represented in the expedition files, and this determined our chief task: the tracing of the wall surfaces for inclusion in a series envisioned by Reisner, to be entitled “Giza Mastabas.” Three such monographs have now been produced, in 1974, 1976, and 1978, and the work of the Pennsylvania-Yale team to date has provided material for at least two or three more volumes. Each mastaba is presented through the Boston photographs, plans, and sections; the objects recorded in the field notes, whether in Boston, the Peabody Museum of Harvard, or the Egyptian Museum in Cairo; and the Pennsylvania-Yale tracings of the reliefs.

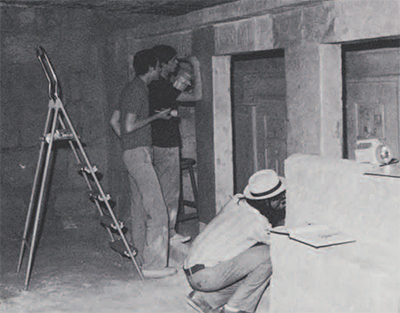

There are several methods of accomplishing this tracing. Our system, while not ideal, is in fairly common use. Sheets of a photographic-type paper with one dull surface are spread over the wall surface and the artist traces the scenes directly on this dull surface using flashlights or other artificial light to see the surface. When the surface is perfectly smooth the paper is transparent, but this is rarely the case. The tracings thus obtained are later, generally in Boston or New Haven, placed on a drawing table and finer pencil retracings made on regular tracing paper, checking the drawing against photographs made by the Reisner expedition. This final tracing is then carefully inked and the final step reduced photographically to one-fifth the original size for publication. There are several disadvantages. The system cannot be used when the wall surface is fragile and flaking; the artist has some difficulty seeing the surface through the dull surface; and the wind and cramped spaces often make it difficult to keep the tracing material against the wall.

Other systems used by archaeologists have their own advantages. The Egypt Exploration Society now uses completely clear heavy plastic sheets of tracing material on which the lines are drawn with a fine flair pen and then recopied on tracing paper. The tracing material can then be wiped clean and reused several times. This requires both the skill of an accomplished draftsman accustomed to the system and retracing at the site, but it eliminates the difficulty of seeing through the dull coated sheets. The best known system is used at the Oriental Institute of Chicago’s project at Thebes. Here photographs are taken and printed with a matt surface on which the artist traces. The sheets are then bleached to show only the traced lines; these are then revised several times by an Egyptologist and redrawn by the artist. This system is useful for large temple walls where tracing directly would involve an incredible amount of paper. It also requires elaborate camera equipment and scaffolding as well as one’s own photographic studio, with precision in the reducing of the photos to scale. It is ideal for a permanent headquarters. Still another method, used by Professor Caminos of Brown University, consists of rubbing with carbon paper on a special type of tissue paper, which is then placed on the drawing board directly in front of the scene and traced on regular tracing paper for subsequent inking. As with our own system the method cannot be used when the wall surface is fragile.

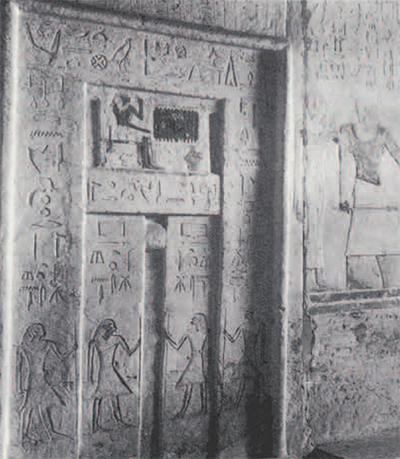

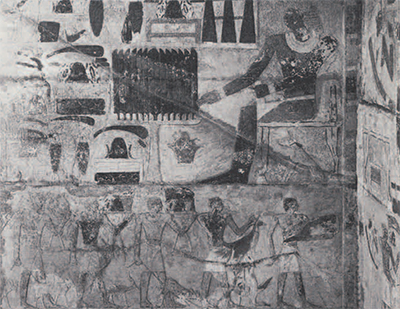

Our drawing of the south wall of the portico mastaba chapel of Tjetu (G 2001) is based on an actual tracing made by the Pennsylvania-Yale project in 1975 with the aid of early photographs and watercolor renderings by the original expedition artist, Norman de Garis Davies. The chapel was cleared in 1905 by Lythgoe, a former student and associate of Reisner, with the aid of A. C. Mace. We hope to include it in the projected Giza Mastabas Vol. 4, scheduled for publication in 1980 or 1981, three-quarters of a century from its discovery! With a backlog such as this it is no wonder that we must give priority to the publication of material already excavated (and rapidly deteriorating) rather than new excavation. The names and titles of Tjetu’s son and lector priest in the lowest register of the wall, visible in part in the photograph, have now completely vanished, as they were not cut in relief and only lightly painted. Similarly, the elaborate spotting of the hair of the dog under his chair and the calf of the offering bearer have vanished without a trace since the time of the discovery of the portico.

Tjetu lived at the very end of the Old Kingdom, probably even after the end of Dynasty VI, and bore the titles of Overseer of the Giza Necropolis, “the Horizon of Cheops,” as well as Inspector of the Purifying Priests of Cheops, King’s Liegeman of the Palace, and the frequently attested office of Overseer of the Tenant Farmers. Standing in the shade of his portico, he could view the great pyramid and most of the great western cemetery. The portico and its court to the east reflected the architecture of his own house, although the three “false” doors of the portico represent the real doors of his own dwelling. Tjetu’s mastaba seems diminutive in juxtaposition to the huge mastaba G 2000 just behind it. The latter is by far the largest in the entire Giza cemetery. Although it has been completely excavated, no fragment of relief or statuary preserving the name of its builder has been found. It is ironic that we should know the names and activities of Tjetu and his family while the very important official of the great mastaba is now anonymous.