The production of reliable spring-temper steel in early times was a difficult and delicate process, so often attended with failure that it came to a certain extent to be associated with magic—not only of the fantastic sort recorded in the Siegfried legend, but also of a practical character where medieval swordsmiths recited charms in the form of verses, prayers, or ritual sentences that very probably served as rough timers during the appropriate tempering through the interrupted-quench method. Successful spring-tempering of steel was accomplished so late that it is reported in literature of earlier date than the oldest specimens where its presence has been established through testing.

The first plausible report is that of Philo of Byzantium, an engineer of Hellenistic times, who asserts that he examined steel sword blades from Spain that had spring temper; the second report, twelve hundred years later, comes from the late ninth century A.D., in the latter part of the life of Charlemagne written by the Monk of St. Gall.

In contradistinction to the arduous and precarious nature of this process, bronze (or brass) can be given spring temper through work-hardening by cold-hammering or other cold-working alone. The simplest, most convincing demonstration of this effect for a nonmetallographer is what happens to a bit of copper-alloy wire when it is drawn successively through smaller and smaller holes in a jeweler’s wire-drawing plate; for such drawing is in fact a very even way of hardening this metal through cold-working on a miniature scale. As the wire becomes more and more slender, it becomes springy. Such a spring is of course a weak one, but it serves to show how the metal behaves under a very simple treatment. Hardness and spring temper in such metal may be produced accidentally to an undesirable extent—in the drawing of brass cartridge shells annealing is required at intervals among draws to eliminate excessive hardness and brittleness as they develop.

Since these qualities arise so easily and indeed automatically, it is reasonable to surmise that the first time primitive man shaped native copper by hammering, he imparted some degree of hardness to it; the first time man made a fibula of bronze he not only hardened the metal, but also produced a degree of spring temper which he could turn to use; and the first time he made a saw blade of bronze by cold-hammering a sheet he produced both of these qualities, of which the first made his saw cut better and the second endowed his saw with some ability to return to its original shape after being subjected to a bending stress.

Bronze saws are recorded in the Middle East from as early as 2750 B.C. In Outils de Bronze de I’Indus au Danube, by Jean Deshayes (Guenther, Paris, with catalog and description of saws in Volume II, pages 152153), example No. 2869, from Mesopotamia and dated to the first quarter of the third millennium B.C., is 50 cm. long, which is to say that its size is already substantial, and that the presence of both hardness and spring temper upon completion of manufacture may be conjectured.

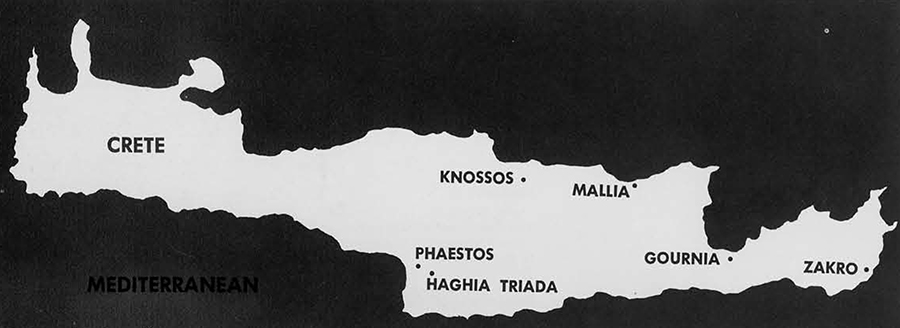

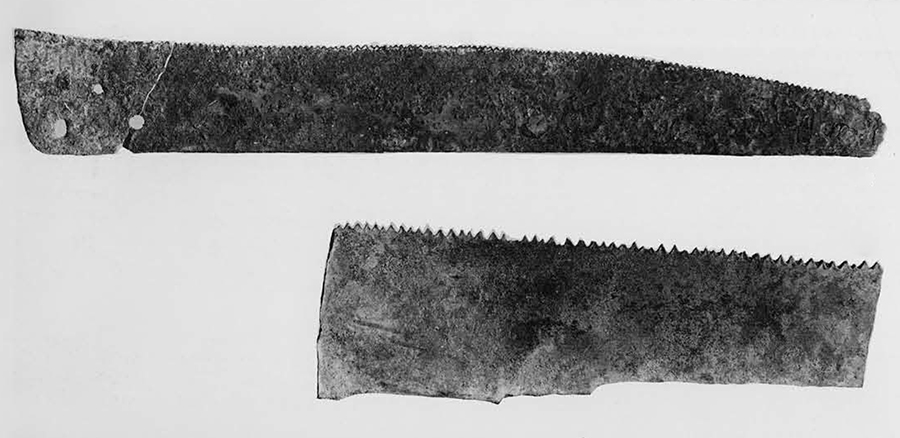

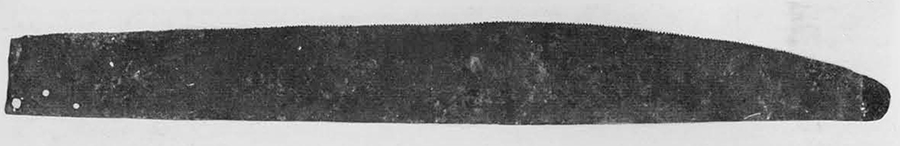

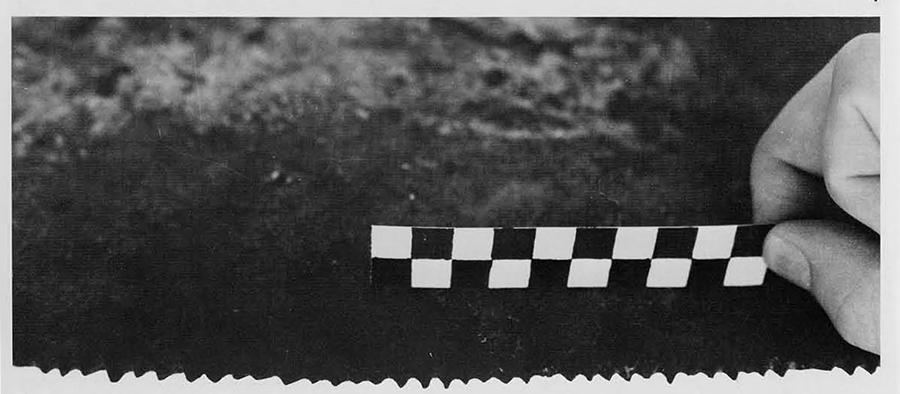

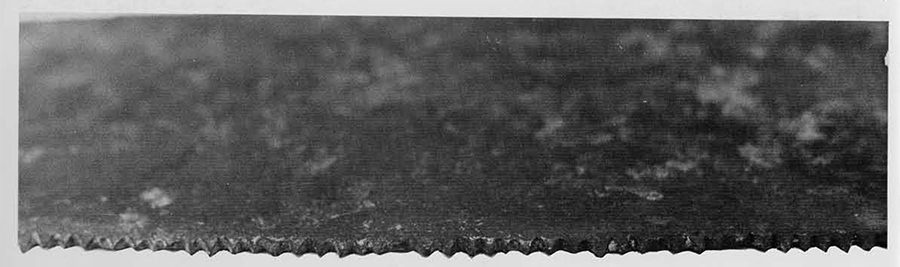

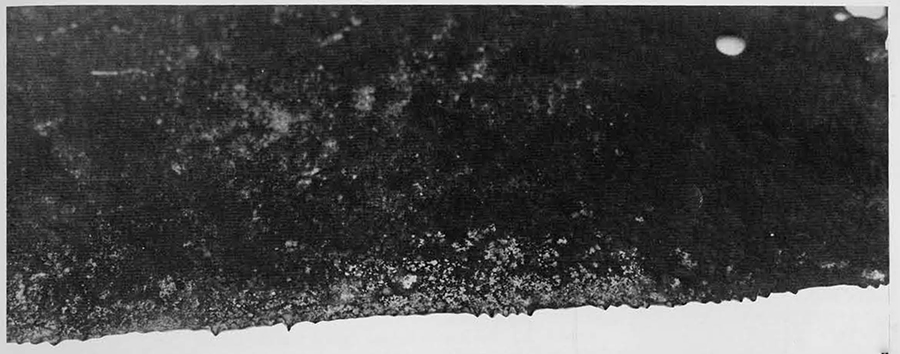

In later Minoan Crete, which is to say about 1500 B.C. or well over a thousand years after the Mesopotamia saw, some extremely large bronze.saw blades were produced, of which perhaps half a dozen have survived in more or less intact form. The principal ones of these range from 170 to 141 cm. long. Breadths run from 21 to 11 cm. The last, extremely slight breadth appears in conjunction with a length of 145 cm. in a saw found at Haghia Triada (see F. Halbherr in Monumenti Antichi, Vol. XIII, 1903, page 67). As might be expected, the Haghia Triada saw, exceptionally narrow in proportion to length, is one intended to have handles at both ends—holes for pins to fasten two handles are present. (Three others, from Zakro, are known; one is 170 x 20 cm.) Other, broader examples have holes for pins to attach the handle at one end, and may have been used by one man only.

Investigators give the thickness of these bronze strips as being about two millimeters and declare that the thickness is very even throughout. My recollection from seeing them on exhibit at the museum in Heraklion, Crete, is that they are indeed of very even thickness, but that they might be a little thicker, or perhaps three millimeters.

As regards the metallurgy of Minoan bronze:

1. At least two quantitative examinations of bronze articles from later Minoan sites have taken place.

One is reported in Gournia, Vasiliki, and other Prehistoric Sites on the Isthmus of Hierapetra, Crete, by Harriet Boyd Hawes (American Exploration Society, Free Museum of Science and Art, Philadelphia, 1908). Mrs. Hawes says “analysis teaches us that Gournia . . . tools and weapons were of bronze containing as much as ten per cent of tin.” Unfortunately, no analyses were made on any of the saws found at Gournia.

The French excavators of Mallia (see below] also refer to bronze containing a substantial percentage of tin.

It seems clear, and natural in the light of the earlier history of bronze tools and weapons, that the Cretans of Minoan times were familiar with copper-tin alloys which, were they to be treated in suitable fashion, would be capable of developing a satisfactory degree of hardness,

- It is also clear and natural that artisans of Minoan Crete were familiar with the technique of beating or hammering bronze, both to give it form for artistic purposes, and to harden it for use in tools and weapons.

Small Minoan statuettes of beaten bronze are illustrated as Plate 27 in Prehistoric Crete by R. W. Hutchinson (Penguin, London, 1962). Messrs. Dessenne and Deshayes in “Mallia: Maisons-2ieme fascicule,” Etudes Cretoises XI, 1959, speak of certain double axes which were found at Mallia just as they came from the casting mold, with their edges straight, and of certain others which had been hammered at the edges to harden them, with the result that the edges, upon spreading under the hammer Wows, had become slightly convex.

- More complete metallographic analysis seems unlikely until metallographers (who would be eager to do the work) are able to persuade the custodians of these treasures that only microscopic damage will be inflicted upon the surfaces of any objects so analyzed.

Even as things stand, we may be confident that the Cretans knew a proper bronze and a proper treatment to ensure that the large bronze saws should be hard. How shall one define their precise position in the history of technology? We have seen that we cannot assert that they had qualities, either of hardness or of springiness, which probably or even possibly had not been known before. Yet the impression they make as one comes upon them, either in exhibits or in illustrations, is powerful. Even the shortest complete specimen, among the class of large saws, is nearly three times as long and more than twice as broad—six times as much surface area—as the largest earlier saw (the Mesopotamia one) which I have found in the literature. These Minoan saws were, as one correspondent remarks, “quite obviously very large and very good.” They reflect not an invention nor a discovery, but in all probability an advance in application of the technique of manufacture, perhaps resulting from a new type of use.

I recall reading that the roofs of the upper storeys of Cretan temples were probably supported on wooden pillars consisting of the solid trunks of trees. Crete seems to have been well wooded at that time, and large pieces of lumber were perhaps more easily come by than in most parts of the civilized communities farther east which produced the earlier bronze saws. It would have been a convenience to cut and finish in a single operation both ends of a tree trunk intended to serve as a pillar. So far as I am aware, the large Minoan saws have been found only at temple sites, and they must have been very valuable.

One may advance the hypothesis that the function of these saws was such as to require (to a greater extent than had been necessary in earlier, smaller saws) that they be good springs. It is impossible to say that the earlier examples were not also good springs—in all probability they were. But the large Minoan saws are of so much greater surface area, and show so little increase in thickness, that they could much more easily be bent if they were subjected to strain in a kerf. Despite this fact, and despite their value, several of them seem to have been operated by a single worker. As might be expected at this early date, the teeth of these saws are not raked in either direction, and it cannot be claimed that the saws were intended to cut primarily on either the pulling or the pushing stroke; most likely, in view of their exceedingly great weight, they did some cutting on both strokes. But even if they were used, with one operative handling them, so as to cut almost exclusively on the pulling stroke, they did have to be returned to position so that the pulling stroke could be made. The chance of strain, with consequent deformation of the saw, must have been a major risk even with the greatest of care in use. Good spring temper in the blade would be of great help in reducing this risk, and since the Minoans made a number of these saws intended for a handle at one end only, they seem to have counted upon this quality’s being present.

There is just one tenuous clue to show us that accidents from binding in the kerf may sometimes have happened. The saw from Mallia mentioned above has been observed recently to be cracked eight or ten inches from the end farthest from its holes for the pins of a handle. The crack runs almost halfway across the breadth of the saw from the back, and a triangular piece of metal has been broken out of the back where the crack starts. Opposite this crack, on the toothed edge, a number of teeth are missing. This might be the result of the saw’s having undergone strain while in use, and since the crack is so near the end of the blade away from the holes one might deduce that the strain arose from a pushing force incautiously applied at the handle end. But of course the saw may have suffered mishap from other causes during the three thousand years that it lay buried, for this has clearly been the case with similar examples which have been found broken into a number of pieces, yet with all the pieces lying adjacent to each other in the soil of the site (this occurred with two of the three large saws from Knossos). Consequently one must not insist that the Mallia saw was cracked through strain while in use.

But it does indeed appear that the Cretan bronze-smiths may have dealt rather confidently with the hazard of buckling, trusting that the spring temper of the metal would protect their saws from remaining bent, or from snapping, if they should be subjected to pronounced stress. A technological advance had occurred which may have been not simply one of scale, but of assurance that the qualities the new scale required would in fact be present.