People we had known only from old photographs and letters suddenly came to life with Edith Siemel’s visit to the Museum Archives. Edith’s husband, Sasha Siemel, a renowned hunter, had been the central member of the Matto Grosso Expedition of 1931, which, with the participation of the Penn Museum, set out to film a documentary in Brazil.

Few Penn Museum expeditions have been as colorful as the Matto (currently Mato) Grosso Expedition. Organized by Captain Vladimir Perfilieff, a Russian-born artist and world traveler affiliated with the Explorer’s Club of New York, and Alexander (Sasha) Siemel, a Latvian who had lived many years in South America as a guide, hunter, and photographer, this was no ordinary academic venture. Siemel had distinguished himself for having learned the art of spearing jaguars from the Guató Indians of Brazil, and the film was to capture him in the act of killing a jaguar.

Funded in part by Fenimore Johnson, whose father, Eldridge Reeves Johnson, was the founder of the Victor Talking Machine Company and a great supporter of the Museum, the expedition set sail by steamer from New York on the day after Christmas, 1930. The long trip took the party first to Montevideo, Uruguay, and then upstream to Rancho Descalvados, located at the headwaters of the Paraguay River in the heart of the Matto Grosso region, which was to serve as expedition headquarters.

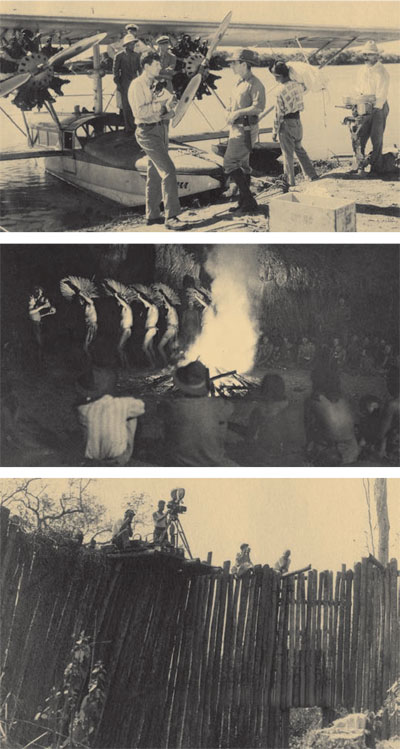

The wildlife of the region included monkeys, anteaters, tapirs, armadillos, anacondas, many types of birds, and much more, but the most prized hunting trophies were the big cats: jaguars and pumas. Expedition members spent time hunting in the countryside or preparing for camera shoots. With the help of a plane, Vincenzo Petrullo, the Museum’s ethnographer, traveled north to make contact with groups from the upper Xingu River basin.

The expedition suffered due to mismanagement of funds, lack of direction, and personal jealousies. Though the film crew managed to get pictures of the nearby Bororo in various staged scenes, as well as some of the wildlife, capturing Siemel killing a jaguar proved to be elusive. The action was simply too fast. The crew even built a corral with a caged jaguar at one end and placed the camera on an elevated platform, but the jaguar would not come out to face the hunter. The expedition ended in September of 1931.

Sasha Siemel was a legend in his own time. Sought after as a hunter to protect ranches from marauding jaguars and to lead hunting parties into the jungle, he was immortalized by Julian Duguid in Green Hell (1928) and Tigerman (1932). He himself wrote about his experiences in his autobiography, Tigrero (1953), and began to lecture extensively. He starred in a Hollywood action series, and was to be the subject of a Hollywood feature film starring John Wayne and Ava Gardner. The film fell through on account of the high cost to insure the movie stars in Brazil (this story is, in turn, the subject of the 1994 documentary Tigrero: A Film That Was Never Made).

Rossi at the camera. UPM Image #27456

Sasha met Edith, when she was 19 years old, at one of his lectures in Philadelphia. They later married and lived in Brazil for a number of years, where three of their children were born, and Edith learned how to hunt and work in the jungle. They acquired animals for the Philadelphia Zoo and others.

During her visit to the Penn Museum, Edith delighted in recounting stories of her many animals. She remembered when one of her jaguars, no longer a cub, jumped her from behind but luckily kept its claws in. She also made some observations on the personality of anacondas. “They are like people: some are nice, but some are really mean.”

The Siemels later moved to a farm in Pennsylvania. Sasha established a small museum in Perkiomenville to display his hunting trophies and weapons, but it closed in 1970, the year he died. Some of his papers are now at the Special Collections Library, Bryn Mawr College. Primitive Peoples of the Matto Grosso can be seen online at the Internet Archive (www.archive.org/details/UPMAA_films). The Hollywood-produced documentary Matto Grosso (1933) has recently been restored through a grant from the National Film Preservation Foundation and is available on DVD from the Penn Museum

It was a usual Monday lunch at the Museum café. Assistant Archivist Maureen Callahan and I were eager to catch up on each other’s weekend. I told her that my husband Albert and I had visited his 91-year-old grandmother, Edith Siemel. “She was married to a…” I hesitated before saying, “jaguar hunter. His name was Sasha Sie—”

Maureen gasped and cried out, “Sasha Siemel, the jaguar hunter?! I know exactly who he is. Archives has photos, film, correspondence, and field notes about an expedition to Brazil. What an unbelievable coincidence!”

According to archival material and family accounts, Sasha Siemel was a self- made man. In 1906, the 16-year-old Latvian stowed away on a ship and eventually wound up in Brazil. In time, he joined the diamond rush to the Brazilian interior, where an old Indian taught him how to hunt jaguar with a spear. Sasha mastered the art and became a professional, paid by ranchers to hunt the jaguars killing their cattle, and by sports men and women to take them on hunting expeditions.

When he lectured at the University of Pennsylvania in 1938, he met Edith Louise Bray, a young Philadelphia socialite and direct descendant of Anthony Morris, the first elected mayor of Philadelphia. Edith also had a connection to the University of Pennsylvania; among her ancestors were brother and sister John and Lydia Morris, who donated the property that is now the Morris Arboretum. That year, Edith went as a paying sportswoman (chaperoned, at her mother’s insistence) to hunt in Brazil. When Edith returned to the United States, she moved to New York City to take a photography course, learn Portuguese, and get to know Sasha better. The following year, the two of them returned to Brazil.

Sasha and Edith married and spent six years in the Matto Grosso jungle rearing two daughters, Alexandra and Dora, and a son Sashino. Edith became a skilled hunter in her own right, even felling jaguars with a bow and arrow. After their adventurous stint in the jungle, the family returned to Green Lane, PA, where Sasha established a museum in Perkiomenville displaying his weapons, Indian artifacts, animal skins, rocks and minerals, sea shells, and other curios. He also continued to lecture in the United States, Europe, and South America as well as take sportspeople hunting in Brazil.

Eager to learn more, the Archives invited me to bring Edith to the Museum. A few weeks later Edith, her daughter Alexandra, and her grandson Albert visited Penn. Edith did not talk much as she and Alex Pezzati, Senior Archivist, pored through old photos of the expedition. Albert reminded her of the stories she used to tell him, many she no longer recalled in much detail. I snapped photos and listened.

The visit passed quietly. Edith was not as vivacious as usual. It was clear that many of the stories behind our archival material would remain untold. But in the end, maybe the visit was not for the Museum; perhaps it was for Edith and Sasha. Seeing old pictures of Sasha in the jungle and reading his beautiful handwriting on the back of each photograph may have brought him back to life for just an hour.