For at least eight centuries, Roman generals marched in triumphal celebrations through the forum Romanum, the central town square of ancient Rome, to display to their fellow citizens booty and prisoners captured in military campaigns. The Roman Empire was a system built on the pursuit of plunder. The irony, of course, is that at no time in human history, with the exception of the modern age, was there such a degree of capital investment in urban infrastructure throughout the cities of the Mediterranean as there was during the time of the Roman Empire, especially in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. This was due, in large part, to Julius Caesar, who initiated an unprecedented colonization program across the Mediterranean. As part of that plan, Caesar organized settlers from Rome to colonize the city of Buthrotum (later Butrint) against the wishes of Cicero and his intimate friend Atticus, who lived at this prosperous seaport on the Ionian Sea. The colonists ultimately arrived at Buthrotum in July 44 BC, two months after Caesar’s assassination. Two thousand years later, in June 2011, an archaeological research expedition in the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Butrint in southern Albania unearthed massive pavement slabs and structures belonging to the city’s ancient Roman forum, which the colonists had built to replicate the town square of their imperial capital.

Funded by the University of Notre Dame and the American Philosophical Society, the excavations are redefining the urban history of Butrint. Unlike Pompeii in Italy, where sterile volcanic deposits rest directly above the ruins of the Roman city of AD 79, the ancient urban center of Butrint is buried deep beneath a multitude of deposits rich in cultural material, the remnants of thousands of years of human settlement. Excavation trenches, dug as deep as 5 m (about 16 ft), allowed us to peer, as if through a window, into the city’s historical transformation from the 5th century BC to modern times. The sequence of buildings and the sections of earth running from the bottom to the top of the trench tell a story of human and environmental actions which have buried the ancient city in tens of thousands of tons of earth and debris. The sheer quantity and array of material evidence generated by the excavations required a team of 40 individuals from eight countries, who worked together on site to help piece together the story of the city’s complex urban development.

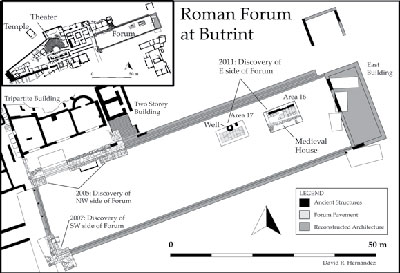

My project co-directors, Richard Hodges (Penn Museum) and Dhimitër Çondi (Albanian Institute of Archaeology), and I had been mulling over a topographical issue since 2005 when we discovered the Roman forum at Butrint. After exposing the western and northern edges of the forum, we spent years speculating what dimensions the forum might have had and whether the eastern side of the forum preserved the same pavement slabs as the western side. Now, six years after its discovery, we had assembled a team to locate the eastern extent of the forum and thereby reveal its complete topographical layout in the city. In an instant, after a month of intense excavation, this long-standing topographical problem was resolved when Tori Osmani, one of the most skilled Albanian workmen, pushed his hand through thick mud and touched the cold surface of the stone pavement, shouting out “dysheme!” (doo-shuh-may), the word for “pavement” in Albanian.

The forum’s dimensions turned out to be 20 x 70 m (65 x 236 ft), much larger than anyone had imagined. The fact that almost all the stone slabs of the paved space remain in place after 2,000 years is remarkable. It is one of the best preserved forums in the provinces of the Roman Empire. Its excellent state of preservation is due to its violent end. An earthquake in the 4th century AD severely damaged the buildings around its perimeter and more significantly led to the inundation of the forum. In an attempt to reoccupy the space, the forum was backfilled after the earthquake in order to raise the level of the ground above the water table. The discovery of a public building of the 5th century AD and later of other buildings and a well from the 6th century show that the area continued in active use until the late 6th century, when burials begin to appear in what was formerly an urban environment. The dramatic downward shift of the city might have been the result of the Bubonic plague, a pandemic which spread across Europe during the reign of Justinian shortly after the mid-6th century.

The urban center of Butrint was later reoccupied in Medieval times. One of the most exciting discoveries from the Late Medieval period was that of a large house, the first of its kind to be excavated at Butrint. We unearthed the northern side of the house, which measured more than 8.5 m (28 ft) across the trench. Built on a foundation of large boulders, the earth-bonded walls were made of small limestone blocks, which were reused masonry fragments from ancient Roman buildings. Patrick Conry, one of four students from the University of Notre Dame who participated in the excavation, found a Late Antique column fragment imbedded in the walls of the building. When we removed the debris of fallen walls, we found that the entire roof of the building had collapsed within the house.

Beneath the layer of large yellow ceramic roof tiles, the ground was burned and it was clear that the timber roof came crashing down while the house was in use. Complete ceramic vessels were recovered from the earthen floor of the house. Large amounts of wheat were recovered from the burned deposits of the earthen floor, using an archaeobotanical system of water floatation. In addition to wheat, we found barley, peas, legumes, and olives. These botanical remains constitute the first physical evidence for the dietary staples of the Butrint region in this period. The presence of food, especially in such quantities, shows that the house was in use when it became engulfed in flames. A masonry hearth paved with thick rectangular tiles built into the northwestern corner of the house indicated that we were excavating the kitchen area.

Three silver coins minted in Venice were discovered on the floor of the house. One was a soldino of doge Andrea Contarini—the elected leader of the Venetian Empire—dating to AD 1368–1382. Coin and pottery evidence dates the building to the late 14th or 15th century, which coincides with the acquisition of Butrint by the Republic of Venice in 1386. The house was destroyed in the 16th century, during a time of intense conflict at Butrint between the Venetians and Ottomans. The exact context of the destruction of the house remains unclear. However, it is significant that the house was never rebuilt and that the destruction debris was never cleared. The destruction of this grand house which stood in the town’s historic center might be linked to the capture of Butrint in 1537 by Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, who used Butrint as a base to attack the Venetians at Corfu.

The most fascinating discovery occurred on the very last day of the excavation. Three Albanian workmen—brothers Petrit, Alfred, and Preni from the Tanushi family—descended barefoot and covered in mud into the very bottom of Trench 16, 1.5 m (5 ft) below the forum pavement. As Catholic minorities in a predominantly Muslim country, these workmen live in Shën Deli, one of the poorest villages in southern Albania. Carrying pick axes and shovels, they were ready to excavate deposits not seen since the remotest times of classical antiquity. Having worked with me on the excavations at Butrint for years, they are skilled and experienced workers who regularly tackle the most difficult work on site.

On this occasion, they were digging through thick dark mud 2.4 m (8 ft) below the water table when they encountered an unexpected deposit. It consisted predominantly of stones and was brimming with cultural material, particularly pottery sherds and animal bones. Some of the pottery sherds were from wine amphorae imported from Corinth (Greece) in the 5th century BC. Many of the animal bones were found burned and broken. Murex shells and remains of marine life soon appeared in quantity amidst the stones. Although we were digging below the center of the Roman city, we had actually encountered the rocky coastline of the Classical Greek city of the 5th and 4th centuries BC.

It occurred to me that the pottery and animal bones were the remains of ancient trash which had been heaped on the coast by the inhabitants of the ancient city. Almost instantly, my mind raced back to an experience I had when I first excavated in Albania nearly a decade ago. I remembered when I set out on a trail to get away from the smell of burning trash in the village only to come upon a gigantic pile of trash on the beach, which to my astonishment had been used by the villagers as a dump site. The beauty of archaeology is that it forces one to see new dimensions of human history, in this case that trash is perhaps a better measure of urbanism than monumental buildings or statues. Under a gray sky and intermittent claps of thunder, we sifted through this ancient trash and rocky rubble. Shortly before dusk, we discovered the numinous face of a goddess figurine from the 4th century BC.

David R. Hernandez is the director of the Butrint Archaeological Research Project and Assistant Professor in the Department of Classics at the University of Notre Dame.

- The Medieval house with a masonry-built hearth and burials dating to the late 6th century AD were found in Trench 16.

- Wesley Wood, a student from the University of Notre Dame, touches the forum pavement after its discovery in Trench 17.

- The silver coin of doge Andrea Contarini dates to AD 1368–1382.

- The silver coin of doge Andrea Contarini dates to AD 1368–1382.

- Preni Tanushi excavates the rocky coast full of ancient trash below the forum pavement in Trench 16.

- The face of a goddess figurine, discovered on the last day of excavation, dates to the 4th century BC.