Of all phenomena, the ability of certain individuals to walk barefoot through fire without being burned is perhaps the most spectacular and unquestionably the most puzzling.

Where and how the practice originated can only be a matter of conjecture. According to some firewalkers, it had its beginning in Central Asia, the ancient birthplace of mankind. Although this claim may very well be true, it is impossible of substantiation. In Europe the practice can be traced back to an ancient Roman family, the Hirpi, who, so Pliny the Elder (A.D. 23-79) tells us, “at the yearly sacrifice to Apollo, performed on Mount Soracte, walk over a charred pile of logs without being scorched and who consequently, under a perpetual decree of the Senate, enjoy exemption from military service and all other burdens.” This event has been described also by the geographer Strabo (63 B.C.-A.D. 21), Virgil (70-19 B.C.), and other early writers.

Whatever the facts of its provenience, the virtually worldwide distribution of the practice of firewalking and its persistence in a period as materialistic and as science-oriented as the present are both indisputable and striking. Today, firewalking is performed in India, Greece, Spain, China, Japan, Bulgaria, Ceylon, Thailand, Fiji, Tibet, and many other parts of the world.

The motivation for firewalking is nearly always a religious one. It may be performed to honor some deceased saint or holy man, to commemorate a miracle once performed on the spot where the firewalking takes place, or in fulfillment of a vow. If performed as an honor to an individual, it takes place annually on the clay dedicated to him.

The Anastenaria of the Greeks in Thrace and Macedonia is a good example of fulfilling a vow by means of a firewalk. In 1250 in the mountain village of Kosti in northern Thrace the little church of St. Constantine one day caught on fire. Lacking any fire-fighting apparatus, the stunned villagers could only stand helplessly and watch their beloved church burn. Then, so the story goes, they heard a groaning from within and hurriedly made a check of their number to see if someone had recklessly entered. All were present. Only then did they realize that the cries were those of the sacred icons, which were calling for help. A few of the braver men rushed into the flaming building, snatched up the icons, and rejoined their fellow-villagers outside without so much as a hair of their heads having been singed. St. Constantine had performed a miracle!

By unanimous consent the icons became the private property of the rescuers, who have handed them down from one generation to the next ever since. Descendants of the rescuers vowed that on each anniversary of the fire they would honor St. Constantine and his mother Helen by walking barefoot through fire, believing firmly that they would escape being burned if they were steadfast in their faith. So, on May 21,1975, a ceremony which has had an uninterrupted history of over seven hundred years was once more performed.

The firewalkers of San Pedro Manrique, Spain perform their ceremony in honor of St. John, holding it annually on St. John’s Eve. The Kadar of Cochin (Southwestern India) walk through fire to pay honor to KundathiKali. They believe that the heat is miraculously transferred to two golden sticks standing in front of the Kali image in the temple. In Thailand, where firewalking is to be seen only in certain villages, it is performed to commemorate the deeds of a local saint. In Bang-sue, a village near Bangkok, it is the culmination of a three-day festival. Both the Lamaist and the Bonist priesthoods of Tibet regard firewalking as an essential part of their rites.

Despite the religious atmosphere surrounding most firewalking, however, the practice is often frowned upon by the orthodox. The Greek Orthodox Church, for example, prohibits its clergy from officiating at these ceremonies, and the firewalkers accordingly try to secure the services of a retired priest of Thracian origin. If they are unsuccessful, the lay leader of the group officiates. In Ceylon, to give another example, there is no connection with the Hindu religion although the firewalk has acquired a reputable status through being performed on the temple grounds.

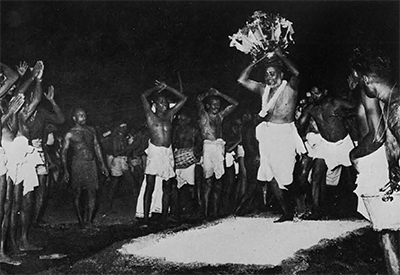

Participants prepare themselves for the firewalk by a rigorous period of purification, sometimes as long as ten days. Among the Kadar those intending to take part fast with their families, take three baths a day, and refrain from buying or borrowing anything and from speaking to a woman. Thracian fire-walkers prepare themselves by a period of silent concentration in the room in which the icons are kept and then by a ritual dance, In Ceylon, where many of the participants are South Indians, there must be no smoking, drinking, or sexual intercourse during a ten-day period. Like the Thracians they also perform a dance prior to the firewalk. During the ten days they are under the observation of the priest, who, to determine whether they are sufficiently charged with the “power,” lashes their bare prostrate bodies with a rope whip. If there is no blood or mark of the whip visible, they are adjudged ready. As a final test, however, skewers and wires are run through their cheeks and the skin of their arms, backs, and chests. The presence of blood bars them from participating.

Thracian firewalkers sacrifice a bull at the Anastenaria, giving the flesh and the skin (for the making of shoes) to the poor. In Fiji, fowls or goats are sometimes sacrificed.

The firewalking is sometimes accompanied by music. In Thrace this is furnished by a drummer, a lyre player, and a bagpiper. The San Pedranos of Spain walk to the accompaniment of the village band. In Fiji the dance which immediately precedes the fire-walk is accompanied by three drums; these represent Siva, Brahma, and Vishnu, the Hindu Trinity.

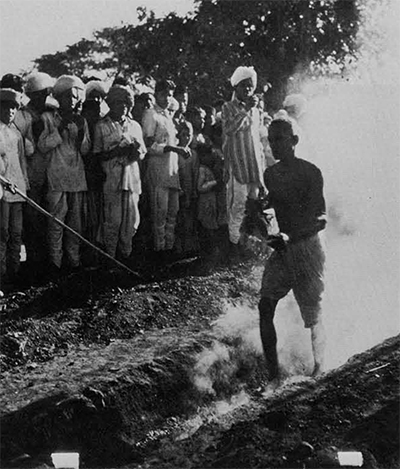

Firewalking falls into two basic types. One of these is the walking over hot stones or other objects, a form prevalent in Polynesia. The other and much more widespread form is the walking over Iive coals. The fuel employed in the latter is usually wood, preferably a kind which will produce red embers retainable for a considerable time. The walking does not begin until the fire is white-hot, with blue gaseous flames flickering an inch or two above the surface. In Ceylon any ashes which may form on the bed of coals are removed by fanning the fire from all sides with huge winnowing fans. All firewalkers agree that stones and other foreign substances must be removed from the firewalkers’ path. The size of the bed of hot embers ranges from three by seven feet in Spain to ten by fifteen feet or even more in Ceylon. The hot coals may be spread on the surface of the ground or may be shoveled into a trench through which the worshipers walk. In Thailand they climb over a mound of burning charcoal.

There is no uniformity in the manner of walking. In some instances the progress of the walkers is unhurried and deliberate, while in others it becomes a frenzied dash across the hot embers. Macedonian and Thracian fire-walkers perform a dance in the center of the bed of fire and even kneel in it. In Tibet and in the Far East the walk is slow and dignified.

Walking on fire was occasionally engaged in among some American Indian tribes, though it appears to have been an individual act and not part of a ritual. Vodun devotees in Haiti also occasionally walk on or through fire to honor certain of the Ion or spirits. And it is an important part of the stock-in-trade of the Asiatic shaman. Firewalking is performed also by the Aissaoui of Algeria but only as part of a performance which includes also the driving of nails into the head, the eating of glass and scorpions, the stabbing of the body with swords, and the avulsing of the eyeballs by means of an iron rod.

When firewalking is performed publicly, as it usually is, the crowd of spectators invariably includes a number of doctors and psychologists. They are always welcomed and permitted to examine and to question the walkers both before and after the firewalk. All confess themselves baffled at the absence of burns on the feet and the lack of any traces of scorching on the garments.

Many theories, none of them wholly plausible, have been advanced to explain the immunity of the firewalkers. It has been suggested, for example, that the speed at which participants cross the bed of hot coals prevents their being burned. As we have seen, however, the walk is often slow and, furthermore, the walkers often remain on the bed of embers for half an hour or longer. Another suggestion made is that the firewalkers are accustomed to go barefoot and hence the soles of the feet are hard and tough. This explanation might possibly be valid in some instances but would not hold good for the alpargata-wearing San Pedranos and the tsarouchia-wearing Thracians and Macedonians, the soles of whose feet are as tender as our own. To say that the feet are protected at least partially by a thin coating of fine ashes is hardly reasonable when, in Ceylon, the ashes are being fanned away during the whole of the ceremony. If, as has been suggested, the feet have been toughened by the application of certain ointments or herb juices, how is one to account for the fact that stockings worn in the fire are not scorched and that fresh flowers carried by firewalkers are not wilted by a fire hot enough to make spectators move back several feet from their assigned seats? To say that performers are in a state of ecstacy or a hypnotic trance which renders them impervious to pain would do nothing to answer the above questions nor would it account for the absence of burns or blisters on the feet.

Perhaps the best explanation yet offered, though this is not a completely satisfactory one, is that the immunity to heat is largely owing to the way in which the firewalkers place their feet upon the hot coals, the principle involved being somewhat analogous to the snuffing of a candle with the hare fingers. In other words, if the foot is placed firmly, the fire immediately under it is momentarily quenched, and before that at the sides of the foot can work in under it, that foot is no longer there. Thus, each step taken is in effect a temporary snuffing out of a small part of the bed of coals.

Can a non-initiate take part in a firewalk without being burned? The answer is an un qualified yes. Britishers in India used sometimes to join the natives in a firewalk and with no ill effects. In Tibet, observers of fire-walking there have sometimes done the same. Probably the most rigidly supervised test of firewalking ever made was that conducted some years ago by the University of London Council for Psychical Investigation. In this carefully controlled test the type of firewalking done in Spain was successfully duplicated not only by Indian firewalkers but also by Englishmen attempting the feat for the first time. There seems to be no explanation.

Despite the considerable amount of literature on firewalking, the subject has not yet been sufficiently studied from a scientific point of view and still remains a challenge to the serious investigator.