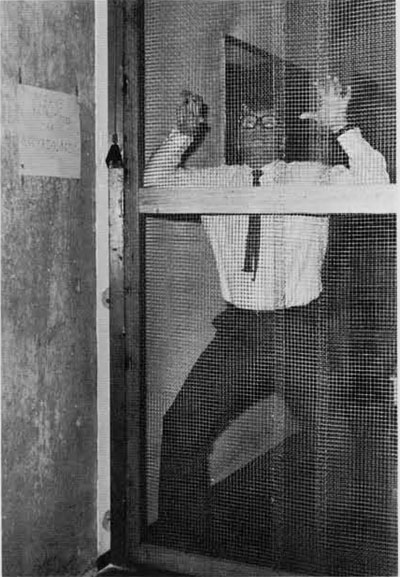

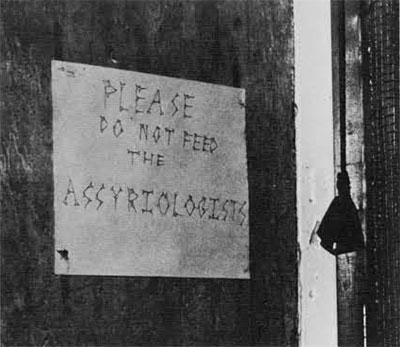

Just above the Kress gallery in the northeast corner of The University Museum lies a little frequented area of the building. Despite the constant flow of traffic to and from the business office across the hall, few strangers find their way behind the cage with its polite warning: “Please do not feed the Assyriologists.” If one rang the cow-bell hanging on the cage and if it could be heard above the squeal of the constantly running photo typesetter in the hall, one might be admitted to the inner sanctum of the Tablet Collections by the boss himself, Ake W. Sjoberg. This genial and occasionally irreverent Swede rules over the dusty kingdom of The University Museum’s cuneiform tablet collection, the second largest collection in the United States.

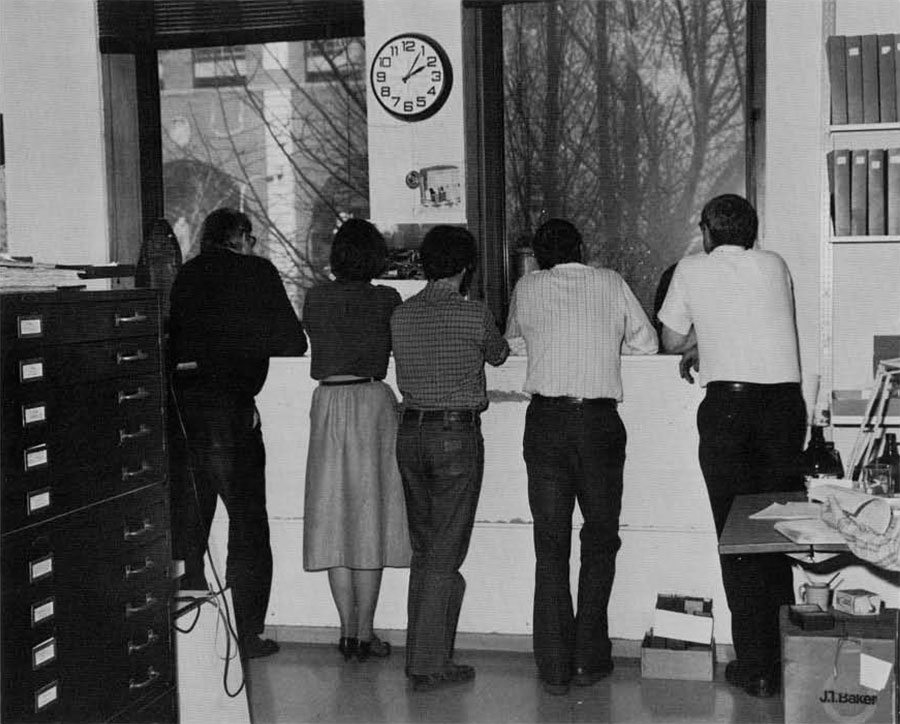

Sjöberg became Curator of Tablet Collections in 1968 upon the retirement of the revered Samuel Noah Kramer. As we all know, Professor Kramer is a tough act to follow. But follow it Sjoberg did: his tenure as Curator has been marked by a contagious enthusiasm and exuberance unrivaled in the field of Sumerology. As many as ten young scholars each day wedge themselves in between the tablet cases in order to enjoy and participate in the excitement and electric atmosphere of the Tablet Room. The thrill of discovery permeates the room as new findings are heralded and discussed.

It was his love of research and his gregariousness that led Sjöberg to undertake one of the world’s great team projects: the compilation of the first Sumerian Dictionary.

The University Museum and the Sumerians are old acquaintances. The very first overseas expedition from the University of Pennsylvania went to Iraq in 1889 and began excavations at the most important of the Sumerian cities, Nippur. The finds at Nippur were one of the first major collections of The University Museum, then known as the Free Museum of Science and Art. Among them were thousands of cuneiform tablets, the majority of which were written in the Sumerian language. Sumerian is a unique language, unrelated to any other known language, living or dead. It was the first language to be written by man. It was extremely difficult to decipher Sumerian, but over a period of time the pioneer Sumerologists, aided by bilingual texts and ancient lexicons, achieved the decipherment.

Since the first study of Sumerian, progress has been very slow. It has been hampered by the difficulty of the writing system, the understanding of Sumerian grammar, and the fact that the language itself is unique. In addition, Sumerologists like Kramer and Sjöberg have had to labor tediously to piece together the broken fragments of tablets to establish a corpus of texts from which a tool like a dictionary could be constructed.

By 1975 a combination of factors coalesced to make the Sumerian Dictionary Project both feasible and attractive. Sjoberg, with his deep interest in philology, seized the opportunity offered by the Tools Division of the National Endowment for the Humanities and applied for a major grant to write the Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary. To the delight of everyone in the Tablet Room, NEH responded with generous funding. To our further delight, the William Penn Foundation gave us a most generous gift of matching funds to supplement the grant.

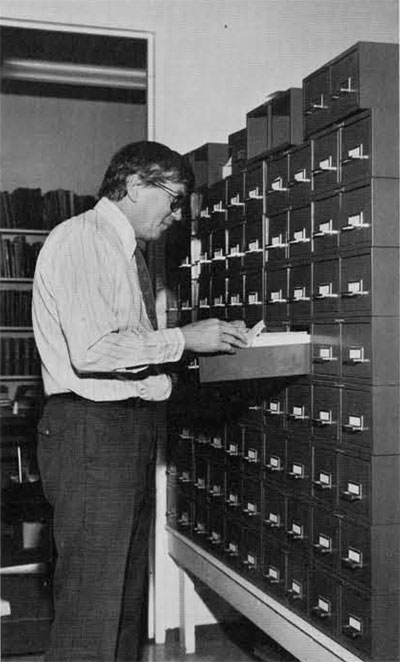

In September 1976, work on the project began in earnest, Sjoberg and a small staff consisting of Dr. Darlene Loding and Dr. Stephen Lieberman began collecting occurrences of words from all types of Sumerian texts. It did not take long to accumulate a small mountain of fife cards. From that time until 1981 the dictionary staff was primarily occupied with data gathering. In the meantime, the NEH showed tremendous support by renewing the dictionary grant twice. Workers came and went. Lieberman left the project in 1979 to take up a Guggenheim grant. He was replaced by Dr. Piotr Michalowski who subsequently accepted an endowed chair at the University of Michigan. The current staff consists of Dr. Sjoberg, Dr. Lading, and Dr. Hermann Behrens. Dr. Margaret Green is expected to join us shortly.

The Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary is not just another dictionary. Words are defined, but in addition the definitions are supported by quoting usages of the words in full context, in much the same way as the large Oxford English Dictionary. This gives the reader an opportunity to feel the niceties and nuances of the word discussed, Such presentation is extremely important when working with a dead language since one can hardly ask a native informant for help!

Today the dictionary dominates the work of the Tablet Room. That is not to say that our other duties are neglected. After all, we will finish the conservation of all 30,000 tablets next year. But, the focus of research lies in the dictionary. Students and staff have had to prepare new manuscripts of the Sumerian literary compositions. In many cases these have served as the basis for dissertations or books.

The Sumerian dictionary is currently in the writing stage. Articles are written and edited by Sjoberg and the rest of the staff. They are then typeset on a computerized photo typesetter. The electronic storage of each article allows extensive editing and revision at any stage of the preparation of the volume. Changes can be entered easily right up to the time a volume is sent to the printer.

We have every expectation that the publication of the Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary will radically alter the field of Sumerology, Because there is no dictionary at this time, the primary thrust of virtually all Sumerological research is philological. Up until now there have been few attempts to branch out, to ask broader questions, or to apply the methodology of other disciplines to Sumerology.

A similar situation pertained in the field of Assyriology in 1956 when the Chicago Assyrian Dictionary first began to appear. Since then the field has been revolutionized. Linguistic analyses and literary analyses are being tried. Computer projects abound. Anthropological theory is being applied. Synthetic works on religion and history appear regularly, and philological work, far from being neglecter has become considerably more sophisticated. The field is progressing at breaknecl speed. Students of Assyriology now learn more rapidly and more thoroughly. Questions are now being asked of texts which could not be posed before the advent of the dictionary.

It is almost certain that a similar knowledge explosion will take place with the publication of the Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary.

The Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary project is one of the world’s greatest projects in the Humanities and it serves to keep The University Museum and the University of Pennsylvania in the forefront of Assyriological studies. Ake W. Sjoberg has given us an enviable example of armchair archaeology!