Archaeological digging is a good deal like prospecting– you never know when and where you are going to strike paydirt. Most discoveries are the result of careful planning but occasionally the excavator is blessed with good luck. Whichever factor is responsible, these unpredictable finds prevent archaeology from becoming routine cut-and-dried research, and serve to stimulate and hold the interest of both workmen and staff in the field.

The third University Museum expedition to the jungle-shrouded Maya ruins of Tikal in Guatemala began excavation there late in January 1958. Long, arduous preparation had preceded this stage of the Tikal Project. Camp facilities were well enough established to house and feed the large labor force and staff required on the dig. Now, we were ready to excavate– a stage we had worked so hard to reach– to uncover the long-buried remains of an aboriginal civilization which so brilliantly flowered and then died some ten centuries ago.

Week after week, we patiently removed the detritus of masonry stairs, terraces, and temple walls– the result of centuries of exposure to the tropical rains and fast-growing plant life. We mapped, photographed, and recorded in field books the observed surface features. The crumbled remains of root-disturbed plaza and terrace floors were delicately brushed by hand– these same floors which once had felt the tread of Maya priests, civilian elite, and commoners. Artifacts of stone, shell, bone, pottery, and other material which had withstood the ravages of time received meticulous attention. All these form the hard core of archaeology.They provide the evidence needed to solve the mysteries of the Lowland Maya– the people who last occupied the metropolis and whose ancestors over centuries and centuries had built Tikal from a hamlet to the greatest of all Maya cities.

These daily activities fully occupied the laborers and staff. It was slow methodical work. We were prospecting. The strike came unexpectedly one hot afternoon in early March. For three days several of our men had been clearing the debris-choked rooms of Structure 34, one of the sixteen temples on the Northern Acropolis. The men worked steadily, as I could see from the plaza below by the puffs of dust rising from each shovelful of dirt they threw out. It was time to make a routine check of the excavation. However, the heat and a series of camp problems had sapped my energy. The climb up the steep-sided pyramid to the temple was not appealing. Bill Coe and Dick Adams, who were digging nearby, kindly offered to have a look.

They climbed Structure 34 and disappeared in the rear chamber. The next moment out popped Bill frantically waving his arms and shouting, “Ed, come quick.” I didn’t know what had happened. Had one of the men been killed by a falling rock? Had Dick been bitten by a snake? I scrambled up the pyramid slope in record time. There was the strike! Paydirt! A new stela, one side partly uncovered showing magnificently carved hieroglyphs and painted a brilliant red. The clamor raised by Bill and my mad dash up the pyramid brought all the other workmen on the run from nearby jobs. They crowded into the room to find the cause of all the excitement. Our enthusiasm was contagious, flagging interest revived, and the whole camp was stimulated by the discovery.

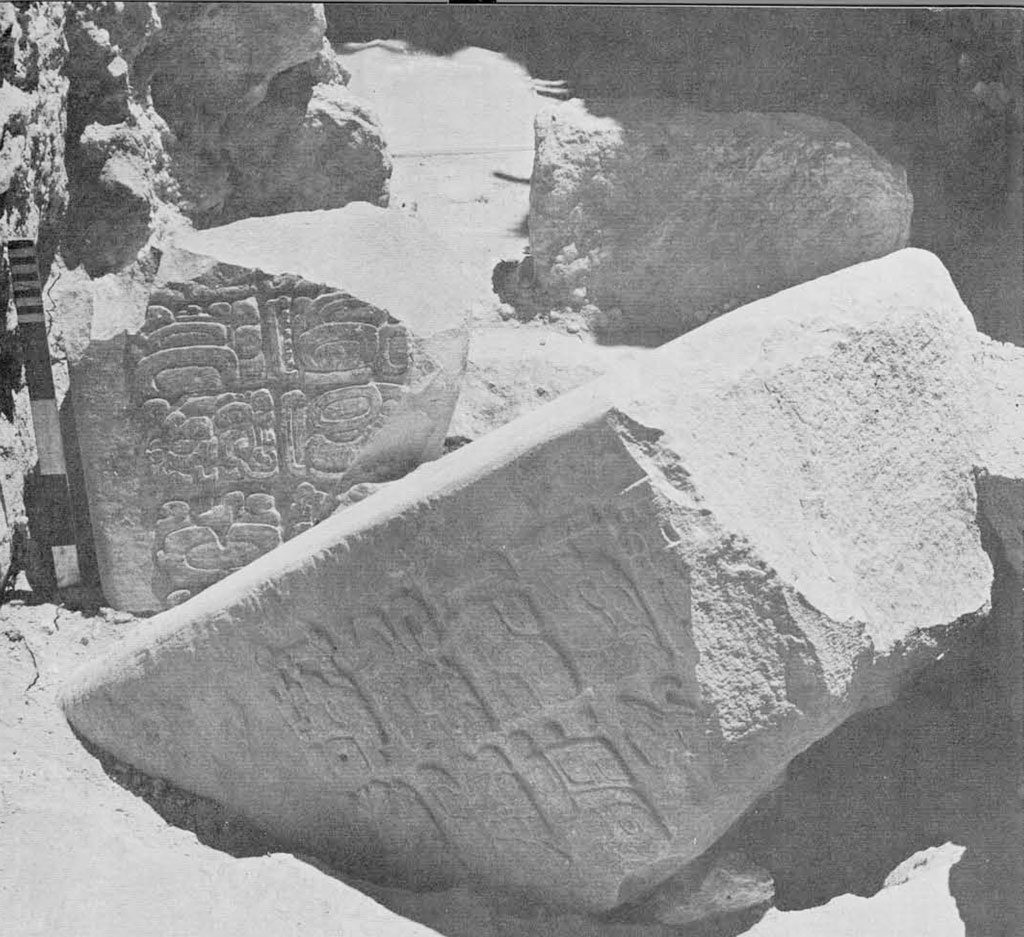

The first glimpse of the red-painted stela, the twenty-sixth sculptured one found in Tikal up to that time, clearly showed that the monument had been broken in ancient times. Stela 26 represents another important example, like Stela 23 and Stela 25 reported lat year in the University Museum Bulletin, of ancient monument breakage at Tikal.

Structure 34, now called “The Temple of the Red Stela” because of the new find, was selected for the initial excavation of the 1958 field season because it is a relatively well preserved and typical example of Early Classic Maya architecture. It is the third of four temples from east to west, which face directly southward on the Great Plaza. These four form the southern edge of the Northern Acropolis– a huge terraced sub-structure supporting a compact group of sixteen temples of different sizes and heights. They appear small, dwarfed as they are by the towering Temple of the Giant Jaguar (Great Temple I) and Temple of the Masks (Great Temple II), but range in height from approximately ten to thirty meters above the Great Plaza. They look like early models for the later great temples. The Maya obviously held this cluster of sixteen temples in high esteem. They erected a multitude of both plain and carved stone monuments and altars on the plaza at the foot of the terrace stairway, on the terrace in front of five of the sixteen temples, and in the rear chamber of the one temple so far excavated. We have, at present, knowledge of 16 carved and 27 plain stelae, together with 4 carved and 22 plain altars, associated with the Northern Acropolis. These stelae represent over 59% of the carved and 34% of the plain stelae known in Tikal.

The Temple of the Red Stela consists of three chambers, one behind the other, and each with a single, centrally placed doorway. Most of the temple’s vaulted ceiling had collapsed except a few sections in the two back rooms. The modeled stucco, painted red, probably fell from the decorated facade of the roofcomb, a small part of which still remained over the rear wall. It was while clearing the six-foot depth of debris from the back room that the workmen discovered Stela 26. Heretofore, pick, shovel, trowel and whiskbroom had been employed, but once the stela came to light only small tools and paint brushes could be used.

Weeks of exciting work followed, each scoop of dirt revealing something new, changing the picture we had postulated at the beginning. To further confuse us, as in most archaeology, we had to observe the physical evidence in reverse order of the momentous events which had taken place in the Temple of the Red Stela. The main sequence, but only tantalizing glimpses at that, could be reconstructed after completion of the meticulous excavations. Additional details must await the results of laboratory analysis of the charcoal, pottery, and various artifacts associated with Stela 26.

However, an outline of major events may be stated with a fair degree of accuracy. The three-room Temple of the Red Stela was erected during the latter half of the Early Classic Period. This is demonstrated by the type of masonry in the temple walls and the style of architecture. Also, two carved and two plain Early Period monuments stand at the base of the temple’s stairway. One of them is dated and apparently in original position. Whether the newly discovered Stela 26 was set up and carved in place at the time the temple was erected we were unable to ascertain, due to the later disturbance by the Maya.

It had originally been erected against the wall of the back room opposite the central doorway. It stood, majestic and awe-inspiring in the inner sanctuary with an elaborately costumed human figure on the front and the two sides handsomely carved with double rows of hieroglyphs. The carved surfaces, visible only to a few worshippers at a time, had been painted bright red. In front of the monument the fire-blackened temple floor provided mute evidence of the reverence paid to the person– priest, ruler, or deity– sculptured on the stela front. How long did the sanctity of this temple with its red stela last? Years, scores of years, or centuries? The answer may be forthcoming through style dating of the sculpture and from radiocarbon analysis of the charcoal recovered below the base of the monument.

The next event in the history of the Temple of the Red Stela was drastic in the extreme. The magnificent monument was ruthlessly broken. Large sections were knocked from the upper half and the delicately carved details of the principal figure hammered into hundreds of chips. These, and many larger fragments, lay around the stela base and well down in a crater-like hole cut through the temple floor, though others were missing. Also, the stela butt had been pulled or pushed forward and its highest fractured edge chipped off.

Subsequently, the Maya seem to have attempted appeasement of the gods for this desecration. they heaped some of the larger monument fragments as well as the many small chips around the toppled stela base. Within this stone pile, and in three separate cache pits dug through the temple floor, they placed rich offerings of highly valued material. Perhaps the deposition of these exotic objects was the culmination of some important ceremony relating to the desecrated red stela. Workmen then sealed the three floor pits containing offerings and built a rectangular masonry altar directly over them, thus burying the stela butt and the heap of fragments and offerings around it. The masonry altar, faced with re-used cut stone and roughly plastered, lay against and centered on the back wall opposite the temple doorway.

The building of the altar marked another phase in the life of the Temple of the Red Stela. We recognize it from the evidence recovered and can separate the earlier from the later events. The temple continued to be the scene of much activity. Smoke from ceremonial fires blackened the plaster on the altar. We discovered a sealed cache of pure charcoal in the temple floor before the masonry altar. How long the temple served as a place of worship, we do not know, but the amount of burning concentrated in front and around the altar does suggest that it functioned normally for some time. We think it a sufficient number of years for the people and priests to forget that the masonry altar concealed a mutilated treasure– the red stela of their ancestors.

Finally, another action took place here which we find most difficult to understand. More desecration! The smoke-blackened masonry altar was partly torn down, thus revealing to the wreckers (or were they looters?) broken fragments of the beautifully carved and red-painted monument with offerings of marine material and fine stone objects. This discovery, still in ancient times we believe, may have startled the finders. They only ripped off a part of the altar. Their wreckage lay scattered around the back room on or just above the temple floor. We also found one fitting fragment of the stela in the debris of the front room. Even more puzzling was their next action. Upon the ruined altar and around the exposed stela, they apparently heaped wood and set the pile on fire. The residue of ash and charcoal from the fire or fires covered the area around and over the altar. Mingled with the ash, charcoal, and debris scattered by the wreckers, we recovered incomplete pottery censers, polychrome vessels and drums, and objects of bone, shell, and stone.

We could detect no further evidence of human activity in the Temple of the Red Stela following the destruction and burning. Seemingly the temple, and perhaps even the whole city of Tikal, was abandoned. Slow destruction by the elements was followed. The wooden lintels over the temple doorways rotted. Most of the masonry vault and the roofcomb fell, deeply burying here for a thousand years the strange, almost incredible story of human behavior. In 1958 men and tools of another age revealed again some of the successes, falterings, and strivings of the Maya.

Once we had cleared the temple rooms, we observed a number of circular cuts in the original floors. Several of these cuts were unsealed, others had been refloored with lime mortar similar but not quite the same as the original floor. We investigated each disturbance. The circular cuts probed to be pits dug through the floor, some for only a few inches, others to a depth of eighteen inches. The unsealed pits contained soft, earthy material, bits of charcoal, and a few potsherds. The sealed ones, previously mentioned as containing caches placed at the time the masonry altar was built, held a surprising array of treasures.

Three pits contained an enormous amount of exotic marine material—sponges, coral, seaweed, sea shells, stingray spines, fish vertebrae, and other strange marine objects. Further emphasizing the importance of coastal products to the inland of Maya of Tikal, there were numerous imitation stingray spines fashioned in miniature from bone. Just as significant by their quantity in the pits were incised and eccentric obsidians, obsidian flake blades, and eccentric flints, some of these beautiful objects being among the finest ever discovered. Other choice items include the mosaic plaque of jade and crystalline hematite mounted on a backing of mother-of-pearl shell, minitature balls of white stone and obsidian, red paint, tiny fragments of jade, and a clay head of a Maya god. These fabulous offerings, virtually duplicated by others from next to the stela base inside the masonry altar, were associated with as yet unidentified plant fibres.

Practically all the contents of these floor and altar caches, with the possible exception of flint artifacts, represent imports from widely separated sources. Some marine material came from the farr-off Pacific Ocean, some from the less distant Atlantic coast. Jade, obsidian, crystalline hematite and red paint are products of the Highlands of Guatemala. All of these items evidently had been selected because of their rarity, beauty, and appropriateness as temple offerings.

However much we ponder human behavior in the past from the limited evidence remaining in an archaeological context, we still wonder how near the truth we really come. The excavation of Stela 26, its temple, its caches and altar, provided one surprise after another. It raised questions of man’s behavior in Tikal which the staff discussed in long sessions around the dinner table and in the laboratory while washing, cataloguing, and photographing the specimens. Why so many richly stocked caches of essentially the same material? Had this great quantity of offerings been looted by the Maya from an earlier cache or burial and redeposited where we found them? Why the emphasis on marine products, some of these never before found in ancient Maya religious offerings? What caused the outburst of violence in Tikal, one manifestation of which was the brutal smashing of a superbly carved monument?

The mutilation of Stela 26 would seem not to be the spontaneous action of a mob. It was a purposeful breakage. A considerable effort and some time were required for the vandals, working only with stone tools, to break up this shaft of limestone which weighed over a ton. Also, the limited space within the temple’s back chamber prevented more than a few violators from entering at one time. The perpetrators of this deed were not content merely to break the monument into large pieces. they intentionally flaked off most of the principal figure. No such flaking showed on the glyphs on the sides of the stela that we recovered; here, the only damage to the glyphs was that caused by the initial breakage of the stela into large fragments. Were the people venting their anger towards the individual carved on Stela 26?

This is but one example of an ancient breakage of monuments at Tikal, all dating from the early period. Often the Maya re-erected a piece of the broken stela, either the upper or lower part, sometimes backward and once upside down. These data raise a host of questions, none of which we can answer at the present time. We are just beginning to probe the rich mine of knowledge hidden so long beneath the ruins of Tikal. What will the next stroke of the excavator’s pick reveal?