At present there are a few hundred of the popular and well-known group of objects called lion bowls, hand bowls, stoppers, or spoons scattered in museums and private collections all over the world, including Japan. Of this number approximately 120+ were excavated and have an objective provenience and authenticity. The sites from which scientifically excavated bowls occur are Boghazkoy, in Anatolia (1); Carchemish and Yunus (several), Zincirli (6), Marash (3), Chatal Huyuk (46), Tell Tainat and Tell Judaidah (29), Merdj Khanis (1), Aleppo (1), and probably Sandilieh (1), all in North Syria (we do not count the bowls said to have been found at Tanjara in North Syria because of the clandestine nature of the finds there and because we do not know what was in fact uncovered. Nor do we know how many modern creations exist in shops and collections under the dealer’s label “Tan-jam”); Ashur [1), Nimrud (13), and Khorsabad (1), in Assyria; Megiddo (4), Tell Beit Mersim (1), Hazor (2), Evron (1), Beth Shemesh (1), and En Gev [1), in Palestine; Hasanlu (3, counting the one published here), in Iran; and, in the West, from Samos (2), Crete (4 or 5), and Ithaca (1). The examples from Crete and Ithaca, four of which are made of pottery, one of ivory, and apparently a fragment of faience, are ancient copies of Near Eastern models.

The bowls occur in a large variety of types and decoration: a tube connects to a hollow lion protome that grips the bowl with its paws; sometimes a hand or floral motif exists under the bowl in addition to the lion; or a lion grips the bowl and there are birds, sphinxes, or lion cubs at the opposite end; or there is a bowl and a tube without a lion, but with a hand or floral pattern motif at the base; or a plain pottery or ivory bowl. Most are of stone except for some pottery examples in the West and one in Israel, an Egyptian Blue example from Hasanlu, the faience fragment from Crete, and the ivory ones from Nimrud (12), Megiddo (1), Samos (1), Crete (1), and the new example from Hasanlu.

The bowls were no doubt joined by the tube to another vessel or container in order to extract a limited amount of liquid, As such they functioned both as a stopper and as a receptacle for the flowing liquid. Whether the containers were pottery flasks as suggested by A. Hoerth, R. D. Barnett, and M. van Loon, or leather vessels as suggested by R. Hampe and R. Amiran, is not certain, but because the bowls are portable, they could have been inserted into any convenient storage-container.

The consensus is that most of them were made at North Syrian sites, and an unfinished example excavated at Chatal Huyuk (information from A. Hoerth) confirms this site as one of the factory centers. In addition, the strati-graphical finds in North Syria, coupled in particular with the Hasanlu finds, establish definitely that the bowls were first made in the 9th century and continued to be made in the 8th century B.C. Moreover, when the bowls are found outside of North Syria, they yield to us valuable information about trade relations between this major artistic area and other cultures.

In 1964, a large number of fragmented ivory objects were excavated at Hasanlu in the Period IV Burned Building II (BB II), which was destroyed in the late 9th century B.C., probably by Urartians. These objects, consisting of pyxides (boxes), dishes, panelling, statues, and inlays, were originally in place on the second story of BB II. When the building burned, the ivories and many other objects fell as the floors and walls collapsed. They were badly shattered and scattered over the south and east areas of BB II. There is hardly an intact ivory object; rather, there are hundreds of pieces, many too small or disfigured for us to be able to reconstruct to their original shape or to make joins. These ivories are now divided among the Iran Bastan Museum in Teheran, the University Museum in Philadelphia, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, but photographs of most of them exist in the Hasanlu Project files.

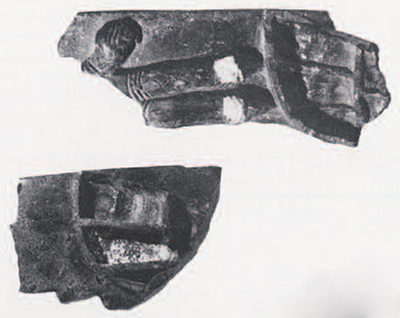

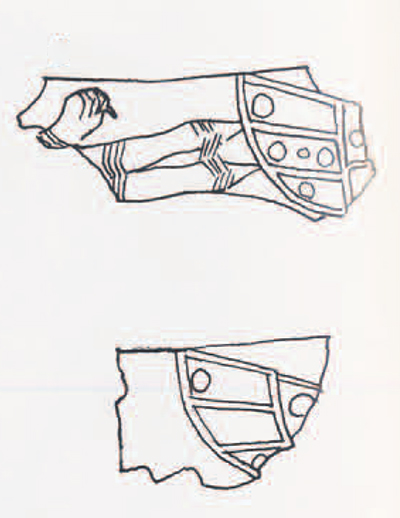

Beginning in 1966, and again in 1972, we began the formidable task of sorting the ivory fragments into categories of objects and motifs. Alas, many fragments were either amorphous pieces beyond recognition or tantalizing parts of a body, garment, or chariot, that is, pieces in need of much additional poring over before they could be assigned to a specific category. One of these fragments (#1, 2 top, and 3 on this page) was a puzzle for some time because it had part of a wing tip, easily identifiable, and a strange inexplicable motif to its left. We assumed that the fragment, and another small isolated fragment consisting only of a wing tip (#1 and 2 bottom) but which clearly was related to the first fragment, were parts of a pyxis, several of which were found at Hasanlu. Both fragments have curved sides and the wings looked similar to those on the sphinxes that decorate the sides of these pyxides. Yet we knew of no pyxis that had the strange motif to the left of the wing. One day in June, 1972, after having examined the photographs half a dozen times in the past, I suddenly realized what the strange motif was and immediately recognized the class of object to which the fragments belonged: the strange motif was part of a paw and claws, and the object was originally a lion bowl. Subsequent examination of the original two fragments in the University Museum confirmed this conclusion. Both pieces had an outer diameter of about 9 cm., providing further confirmation that the two fragments indeed came from the same object.

The length of the larger fragment is 4.1 cm.; of the smaller, 2.5 cm. Both were carefully polished on the interior and rim. The lion’s paw and claws are very stylized and neatly carved by a master artist. Extant are three claws, the uppermost placed at an angle to the others, each with two sets of wrinkles; traces of gold foil still exist, suggesting that the whole bowl originally may have been overlaid with gold. The claws are separated a bit from an a jour wing, which once held inlays; the markings of a hollow drill are visible in both wing fragments.

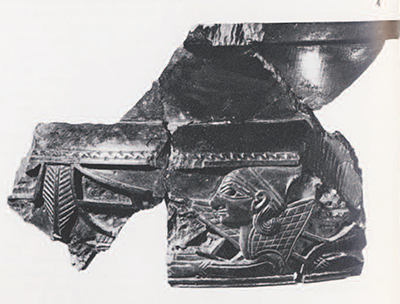

As mentioned above, two other lion bowls have been found at Hasanlu. One, the only example known in Egyptian Blue, is complete; it also came from BB II’s second story but was found fallen into the anteroom at the northern end of the building. The other, in two fragments and of stone, was found out of context in the upper fill but is also certainly from Period IV. Both have been published and are well known. Our fragment now adds another example. Thus there are now three lion bowls, each of a different material, that have been excavated from 9th-century Hasanlu. The University Museum may count itself fortunate because it has fragments of two of these bowls, the stone and ivory ones; while the most beautiful and complete example, of Egyptian Blue, is in the Iran Bastan Museum in Teheran.

Because the Egyptian Blue bowl from Hasanlu, a steatite bowl from Ashur, and an ivory bowl fragment from Samos have the same basic construction and motifs, the Hasanlu ivory fragment can easily be reconstructed. We have, then, the forepart of a lion with open mouth grasping the upper sides of a bowl; a tube behind the lion passed through its body and emptied into the polished interior. Two winged creatures, possibly sphinxes, were symmetrically placed on the side opposite the lion with their heads probably facing out, possibly to guard the contents. #1, 2 top, and 3 on page 26, illustrate the preserved right wing of one sphinx; #1 and 2 bottom, the right wing of the other. Whether the bottom of the bowl was plain, like the Samos bowl, or had a hand like the Egyptian Blue bowl, of course, cannot now be established.

To be sure, we cannot positively reconstruct the winged creatures specifically into sphinxes (cf. #5, 7), or birds (cf. #8); we assign them this identity because their wings are the same as those on the sphinxes adorning the pyxides (#4). And it is concluded that they faced out because we see that the Hasanlu Egyptian Blue and Ashur sphinxes faced out (the Samos birds, on the other hand, faced to the side; information from B. FreyerSchauenburg).

Museum Object Number: 65-31-400

The ivory bowl is definitely very close to the Egyptian Blue example even though the wings and claws are rendered differently: after all, the former was carved, the latter cast. But both bowls have a lion whose claws do not overlap the wings, and whose upper claw is set off at an angle; both have the two symmetrically placed sphinxes; and both were covered with gold foil. The ivory bowl is also quite close to the Samos example, especially in the carving of the claws with the double set of wrinkles and the offset upper claw. Here, however, the claws overlap the winged creatures, clearly birds, and the wings are solid, decorated in a conventional incised fashion. The Ashur bowl also has the lion and two sphinxes but is not so finely carved as the Hasanlu ivory bowl; the paws and claws, and the wings are cruder in execution.

Parenthetically, it is of interest to note that the prominent offset position of the upper claw of the Hasanlu and Samos lions is the same as that on a lion executed in relief on a bronze beaker from Iran, and also on lions depicted on ivories said to have been found at Ziwiye, in western Iran.

The Ashur bowl was found out of context and has no stratigraphical reference upon which to base a chronology, but a 9th- or early 8th-century date is probable. The ivory example from Samos was found associated with material dated to the first quarter of the 7th century B.C., according to H. Walter and B. Freyer-Schauenburg. But it is indeed possible, judging from the Hasanlu evidence, that this bowl may have been in use for some time, perhaps a hundred or more years, before it was deposited in the sanctuary where it was found, a situation not unique for Oriental objects found on Samos. It does not follow, of course, that the 9th-century date of the Hasanlu Egyptian Blue and ivory examples must date the similar bowls from Ashur and Samos to precisely this time, but one cannot exclude the possibility that all the bowls under discussion were manufactured within a relatively short period of time.

It should be noted that there are several other bowls with similar decoration but which are not close enough to bring in as parallels to the Hasanlu ivory example. An unpublished fragment of a stone bowl excavated at Chatal Huyuk, now in the Oriental Institute and kindly shown to me by Alfred Hoerth, has an Imdugud-type bird facing out with tucked-up legs and with carved zig-zag wings; nothing else is preserved. But on a complete lion bowl in the Rockwell Nelson Gallery of Art in Kansas City there are two of these Imdugud birds, ‘exactly the same as on the Chatal Huyuk fragment; the base is decorated with a floral motif. And on a bowl purchased by the Louvre there are two birds opposite the tube end, but no lion, and with a hand at the base. These bowls are of some interest to us here because they ave winged creatures carved on the sides.

Every archaeologist knows that a fragment of a given object may turn out to be of some importance and may be reconstructed to is original form mentally and on paper. Pot-herds become pots; fragments of ivory, pyxides; pieces of fresco, a whole wall scene. And, while the fragment often remains artistically unassuming, its archaeological and historical value can be as great as if the object were completely preserved.

Two fragmentary lion bowls have now been excavated at Hasanlu and reconstructed on paper, giving the interested scholar some idea of their original appearance. These reconstructions prove very neatly that the many hours devoted to examining and reexamining fragments are time well spent.