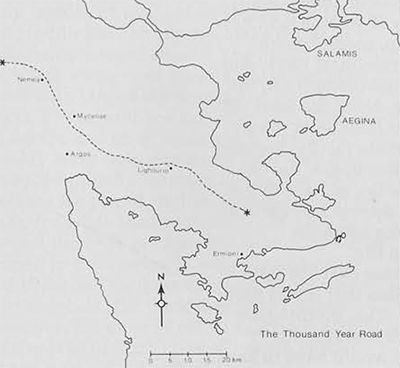

As the parched and brittle wheat fields flashed by the window and familiar smells of rock rose, thyme and pine blended with the diesel of our bus, my mind turned to Nikos and his family, It had been a had winter. Now, just after Easter, when the grain fields should stilt have been a rich green and delicate wild flowers should have touched the land with a variety of subtle colors, the fields wore a mixture of yellows and browns. The life-bearing winter rains had been late and inadequate. Many fields had not even been planted. Why bother when the reward was sure to be a few bare and stunted stalks? There would be no joy this year when Nikos would make the day’s walk down from his winter home on the slopes of Ortholithi to settle his account with Kapetanos Andonis, his cheese merchant. There had been little milk to sell this winter. Nikos’ only hope would now lie in the possibility of late spring rains. Two days later these came. Perhaps the dark rain clouds were also massing one hundred kilometers to the west on the steep slopes of Ziria and Aroania. If so, the summer pastures on these mountains might offer the rich natural grazing necessary both to extend milk production and to ensure that the ewes and does would be in good condition and bred when the flocks returned to the Argolid next November.

As the parched and brittle wheat fields flashed by the window and familiar smells of rock rose, thyme and pine blended with the diesel of our bus, my mind turned to Nikos and his family, It had been a had winter. Now, just after Easter, when the grain fields should stilt have been a rich green and delicate wild flowers should have touched the land with a variety of subtle colors, the fields wore a mixture of yellows and browns. The life-bearing winter rains had been late and inadequate. Many fields had not even been planted. Why bother when the reward was sure to be a few bare and stunted stalks? There would be no joy this year when Nikos would make the day’s walk down from his winter home on the slopes of Ortholithi to settle his account with Kapetanos Andonis, his cheese merchant. There had been little milk to sell this winter. Nikos’ only hope would now lie in the possibility of late spring rains. Two days later these came. Perhaps the dark rain clouds were also massing one hundred kilometers to the west on the steep slopes of Ziria and Aroania. If so, the summer pastures on these mountains might offer the rich natural grazing necessary both to extend milk production and to ensure that the ewes and does would be in good condition and bred when the flocks returned to the Argolid next November.

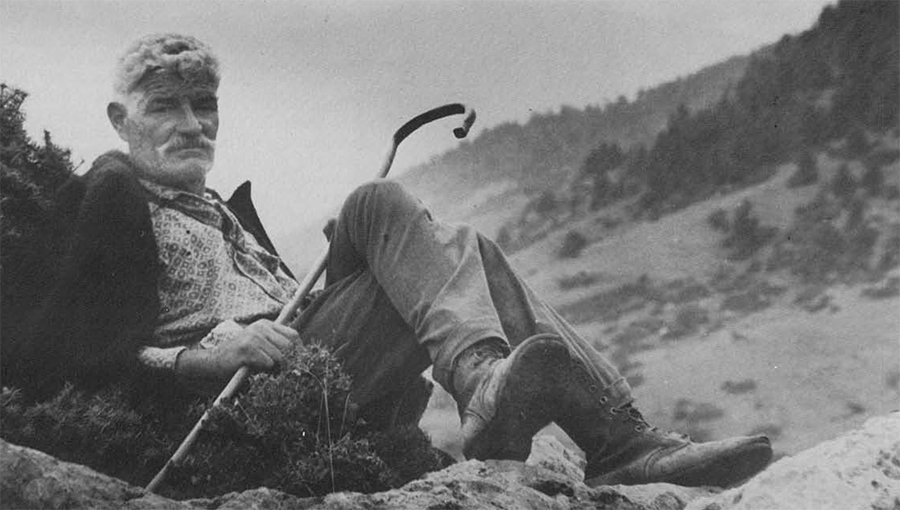

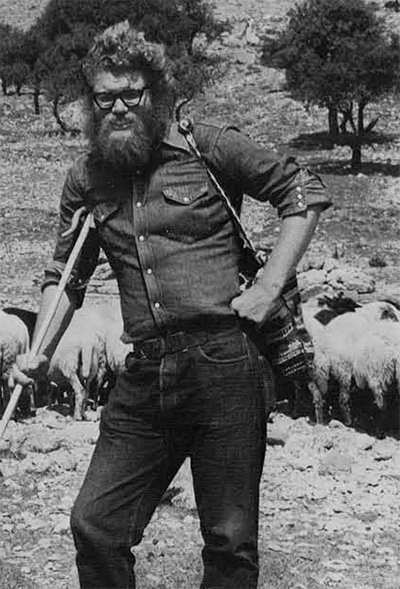

I had first met Nikos in the spring of 1972 when my wife and I conducted extensive research on both contemporary and historical systems of herding in the Argolid. When we first walked out of the mountains into the open yard of his winter home with an introduction from his brother-in-law, Nikos had been naturally skeptical of two young Americans who were genuinely interested in learning from him. He finally agreed to my accompanying his family and flock of six hundred sheep and goats on their return trek to the summer pastures high on the shoulders of Ziria, the greatest mountain in the northern Peloponnesos. It was during this six days’ walk that our friendship was forged in the dust and heat of the road.

The moon had not yet risen when at midnight we were gently shaken from our sleep by Nikos’ wife, Eleni. Everything was ready. The sheep and goats had been milked in the evening and were now locked in the fold after they had been counted and had had their bells checked. For three days we had rushed about in a constant effort to complete the necessary preparations for the road. The stable had been cleaned and the manure hastily spread around the base of many of the family olive trees. Plow and harness, ropes and other working gear were gathered and stored for use next winter. Nikos had returned from settling his accounts with the storekeepers in the villages below, and with his cheese merchant. A goat had been slaughtered to provide a feast for friends and relatives who had come the previous evening to wish us a safe journey and a good summer. The remainder of the boiled meat had been packed by Eleni and her daughter Ioanna for the trip. Milking pans, cheesemaking pots, blankets, capes and clothes necessary for the road had been set aside. The household belongings needed when we reached the home village in the mountains of western Korinthia had been collected, and together with the winter’s production of olive oil, the spring wool clip, the chickens and several sick sheep, had been loaded into a large truck. Finally, Ioanna and her brother Panos climbed into the truck and the driver began his five-hour ascent to the high mountains. After five nights we would join Ioanna in the mountain home, empty for six months, which she would clean and prepare for our arrival.

The older ewes had sensed the excitement and activity in the cluster of small stone houses which lodged the descendants of Nikos’ grandfather. A century earlier, this patriarch had purchased the large, mountainous pasture area which still supports the flocks of six householders who reckon him as their most important ancestor. In those less-secure times, many shepherd families attached themselves to the households of wealthier and more powerful shepherds who could offer both physical and economic protection. By pooling labor, capital and animals, these small shepherd corporations, or tselingdta, could effectively compete for the larger, seasonally available pastures of monasteries, communes, and wealthy landowners. The leader of such a group was called a tselingas—Nikos’ grandfather was such a man. He led a group controlling over two thousand goats and sheep.

As we filed out of the protective warmth of the stone house, which was piled high with stores to be left for the summer, each man reached for his crook hung by the door. Nikos and his sons Panos and Kostas had passed the long days on winter pasture cutting wild olive and briar, and had carefully seasoned and carved these light and pliant crooks decorated with fanciful serpents. These staffs were to be our constant companions for the coming week.

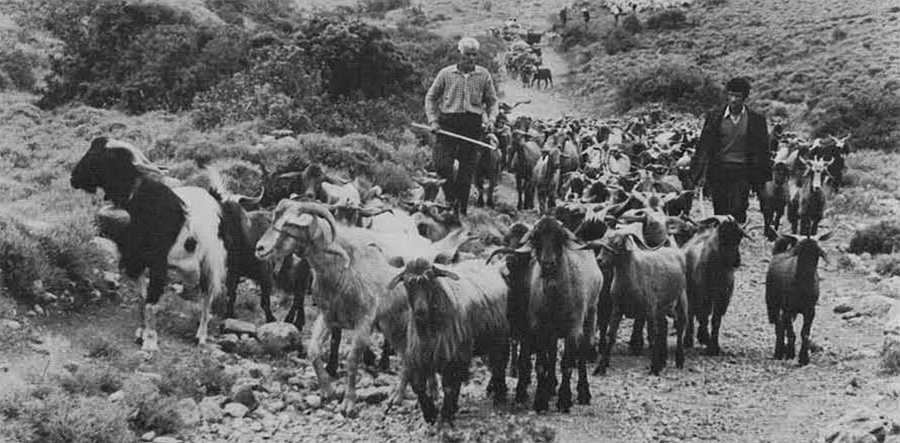

When I reached the stone-lined threshing floor where Nikos waited, smoking another in an endless chain of cigarettes, I could hear the calls and sharp whistles of Kostas moving the sheep out of the fold. In the black of the night, these mixed with the shouts of Spyros Kalives, his son Giorgos and daughter Dimitra, urging the goats out of the security of their nearby fold. Spyros’ wife, Marina, is Nikos’ first cousin, and in the past they had herded with Nikos and several of his brothers in a tselingata. Five years ago, the brothers disbanded their herd, and only Nikos continued on the road of his ancestors, arguing, “If I can no longer follow the goats I will die.” One brother sold his share of the flock and went to work as a welder in the great shipyard of Skaramangas, near Athens. Another married a woman who inherited a rich lemon orchard on the well-watered coast below the rocky slopes of Ortholithi. Although Spyros still has his flock of two hundred and fifty goats, the advantages of the tselingata no longer apply, because most large tracts of grazing land have long since been broken up, credit can be extended through the Agricultural Bank, and the modern state has brought security to the remote mountain hamlets. Now, the most efficient system for shepherd families is to rely on the labor of the immediate family, keeping smaller but more productive flocks. For the week required to push the flocks back to the high pastures, Nikos and Spyros had agreed to travel together, and once again the tselingata would flicker to life.

Kostas started the sheep past the threshing floor and Nikos signalled that it was time for me to rouse the goats. This morning we would have our hands full, because for at least a day the three of us would have to herd the flock without Panos’ help. He had accompanied Ioanna in the truck so that her honor would not be compromised by arriving alone in her home village with a strange truck driver. Two days before we left, Panos’ leg had become severely swollen from an infected tick bite which made walking for him both difficult and painful. It was uncertain if Panos would return with the truck and be able to join us on the road.

Nikos had delayed the date of our departure to take advantage of a moon approaching the full; but, since it had not yet risen, only soft starlight penetrated the dark mountainside over which our flock grazed. Slowly guiding the edgy animals across dark fields and open ground, we finally reached the rough, cross-country track. I stumbled, and asked Nikos how we located the track when I was unable to avoid tripping over a small rock in the dark. He answered simply, “It seems as if I have been on this road for a thousand years.” In many ways he had. Kostas led the sheep out first, with the bell wethers at their head, and Nikos followed leading the goats. I was responsible for pushing the flock from behind and hastening the constant groups of stragglers. Spyros, Giorgos and Dimitra followed at some distance with their goats.

Walking behind the goats I felt the soft brush of a dog’s tail. It was Tsopana, “Shep,” a good-sized dog Kostas had raised from a pup, who felt it was her sole duty in life to protect him, his family and their flock. In Greece, although shepherds keep dogs, they do not use them for herding the sheep or goats as in western Europe. Dogs are kept for protection. Until recently, the depredations of wolves were a real danger, and jackals and foxes still present a threat to the lambs. Large mountain dogs like Tsopana offer very real protection against these predators as well as against packs of wild dogs which often roam in the vicinity of villages. They also serve as watchdogs. But the tasks of herding are left entirely to the shepherds.

The sheep and goats are controlled by a combination of well aimed stones and sticks, the prodding of the crooks, and a series of calls, whistles and shouts. The flocks also have bell wethers as leaders, castrated buck goats with large bells suspended from their necks. These wethers, raised as pets, fed family scraps and given names to which they quickly learn to respond, are kept with the sheep, eventually learning their place. Bell wethers are prized, and shepherds pay up to $300 for a fine lead goat. They are used to control the flock because they are more easily trained in the system of whistles and calls, and if the bell wethers respond to the shepherd’s signals, the flock generally follows. However, the most effective and frequently used means of flock control remain curses, stones, and a good pair of legs.

We had been walking for three hours and the moon had risen, when we saw the flickering gleam of the oil lamp in a roadside shrine marking the meeting of our track with the road leading to Nafplion and the plain of Argos. By the time we reached the village of Trakhia, the sun had risen and Nikos called a halt. He strode into the roadside tavern, whose sleepy keeper was just opening for the day, and demanded a kilo of the finest wine the house could offer. We were soon engaged in conversation by several other shepherds who had come to the shop for a glass of wine before going out to their flocks to assist their sons with the morning milking. Nikos quickly directed the conversation to the subject of which flocks had passed, when, and their destinations, in an effort to form a better picture of the traffic he might expect on the narrow right of way.

As Spyros and his children came up with his goats and he joined the small circle of men, Kostas and I moved our flock down the road toward Lighourio, leaving our companions at the taverna. The sun was rising quickly now and we still had two hours’ walk before reaching the point where the motor road would suddenly swing in a wide circle to avoid the hills enclosing the Sanctuary of Asklepios at Epidauros. Traveling to the northwest, we would follow the ancient trail, which concerned itself less with the grade than with direction and distance. We wanted to push our flock along the asphalt as quickly as possible because later in the morning motor traffic would increase, making our job more difficult and risky.

Three hours later, when we reached our pre-arranged camp in the hills southeast of Epidauros, both Kostas and I were on edge. It had taken much of our strength to herd the flock by ourselves, constantly pushing the animals, shielding them from oncoming trucks and cars with our crooks and bodies, chasing the lambs and kids from the few gardens we passed, and the hungry sheep and goats from olive trees along our route. Relief finally came when they were able to graze freely near our camp made under two large, wild pear trees on the margin of several fallow fields. The goats could graze the mountain slopes belonging to the villagers of the local commune, while the sheep grazed both mountain and fallow. Under Greek law, shepherds are accorded the free use of such common lands for a period of twenty-four hours, before they must move beyond the commune boundaries. This law was promulgated in an effort to minimize conflict between pastoralists whose flocks are on the move, and farmers who jealously guard their ripening grain, vineyards and orchards. Customarily, shepherds are also free to graze fallow fields close to the right of way which are not fenced or marked by whitewashed piles of stones.

Soon after Giorgos and Dimitra, without their father Spyros, brought up their goats and joined us, I looked back down the trail and saw the welcome sight of Eleni and Marina leading their heavily laden mules and donkeys. They had rested until sunrise from the exertions of preparation for the road, and had then set out with the pack animals to meet us by midday at this camp. When they reached us it was obvious that they were angry—their men were not here. Little was said, but from the few sharp comments which were dropped as we constructed the make-shift milking pen or strunga from the pack saddles covered with blankets, the baggage, and some cut branches, we could all sense trouble brewing.

While we urged his goats into the stranga, Spyros showed up with a sheepish grin. Marina immediately upbraided him for drinking, but Kostas broke in saying there was milking to do. In May, the sheep and goats must still be milked twice a day if the milk flow is to be sustained, and this task is one of the most troublesome aspects of the journey from the lowlands. In early November, when the flocks once again move down, they are not in milk, thereby easing the descent for the shepherds. Conversely, at that time the ewes and does are in the later stages of gestation, and the shepherds must constantly be alert for an animal which may leave the flock to birth or may require assistance.

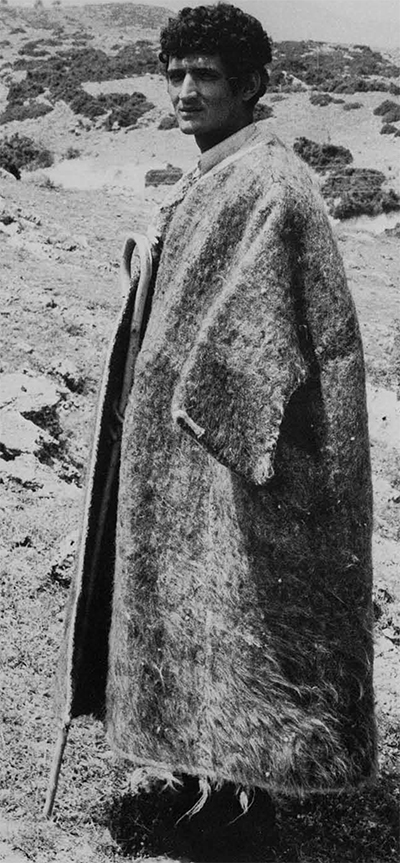

After both flocks had been milked, we spread thick goat hair capes under the trees and ate the meat, cheese, bread and tomatoes and drank the wine the women had brought with them. While we were eating, Eleni and Marina heated the milk to make the morning cheese. Having talked for some time, we took turns herding the animals while the others slept. After our four-hour stop, the extreme heat of the noonday sun had moderated and we were ready to move on, leaving the women behind to finish the cheese and to catch what sleep they could.

The sun was in our eyes as we passed above the theater of Epidauros. Slowly we threaded our way among tour buses on their pilgrimage to the Sanctuary. Here we had hoped to slake the animals’ thirst, but the dry weather and the shepherds who had preceded us had drawn most of the water from the old public wells. Panos, back from the mission of escorting his sister by truck, was waiting for us with the news that Nikos was at the next camp. just south of Lighourio. His leg still swollen, Panos had made the effort because he was aware how important it was to have enough hands to work the flock safely. His return cheered us, but Kostas’ anger with his father could still be sensed.

Twilight found us at the next camp where Nikos rejoined us. Eleni and Marina had set up the strunga. Two other flocks were sharing the ground, both having left Trakhia before us that morning. For Eleni, it provided an occasion of reunion with one of her brothers, who was leading these flocks. He was heading for his home pastures above the village of Limni in Arkadia. Not having seen one another for over a year, they rapidly exchanged news of kin and friends.

This happy meeting partly diffused the tensions of the day, but as we turned to the evening milking, Kostas and the women reproached Nikos for failing to overtake us earlier, Harsh words were traded, Kostas swearing that he was through with shepherding and that he would join his older brother in the merchant marine. The combined tensions of such a disappointing winter had been brought to a head by the hard conditions of the road. Kostas and his father reflected the pressure felt by the entire family to earn cash to provide a suitable dowry for Ioanna, who, at eighteen, should soon marry. None of the sons felt free to marry until they had seen their sister provided with a good husband, and the winter had represented a set-back in their plans. Finally, Eleni’s brother and his wife intervened and smoothed feelings as best they could.

Wrapping ourselves in goat hair capes, we lay back in the prickly bushes dotting the campsite and shared a warming cup of coffee.

Kostas’ godfather arrived and sat in the glow of the fire under the large cheese pot. A shepherd who had settled on the outskirts of Lighourio, he frequently offers Nikos hospitality. Tonight we had not stopped for a meal and talk because of Eleni’s and Nikos’ visit with her brother. The godfather and his wife came to share news and collect the day’s cheeses, which were offered him as a gift.

At midnight we set out to reach our next camp on the lower slopes of Arakhneo, above the Argive Plain. Nikos moved his flock according to a careful plan. Rich agricultural areas and population centers present major obstacles to the moving flocks. It is best to pass these potential sources of conflict in the cool darkness when the flocks can make faster time. All night we travelled through the deep olive groves in the vicinity of Lighouria.

By midday, gathered on a steep ridge overlooking the storied plain of Argos, we could see, rising through the haze, the deep green citrus orchards merge to the west with the silver green of olives to the north, Two years earlier we had camped below on the verge of the plain in an olive grove which offered shade from the intense heat of the sun, but that camp, now fenced, was denied us. Only this bleached limestone ridge remained available as a staging point from which to cross the Argos Plain into Korinthia. Eleni’s brother had camped several hundred meters below and was joined by another flock moving west from its winter pasture beyond Arakhneo. Flocks headed for the mountains of Arkadia and Korinthia were funnelled to this bottleneck—the most direct and least difficult path across the plain.

Anxiety and ambivalence once again filled the oppressive noon air. “Where are my cigarettes? Who will go with the goats? No, I didn’t ask for my cigarettes! When are we going to eat? What, the same old food?” The two words on everybody’s lips—agonia and drama—need no translation. Young Dimitra insisted on staying with her father’s goats to give both Spyros and Giorgos a needed rest. She was as good as any boy,” and would hear no talk of sleep. Nikos took up his station perched on a crag from which he could survey his goats. The rest of us searched the bare ridge for shade, but were reduced to throwing down our capes and thrusting our heads as far as possible into the thorny evergreen shrubs to gain what little shade they could offer.

Dust rose from the closely spaced flocks as we descended to the plain. The sight of several thousand head on migration, trailed by the women and pack animals, brought to mind ancient descriptions of Spartan armies on the march, led by flocks of sheep and goats which they would sacrifice to the gods. Throughout the night the sounds of bells and shouts could be heard, occasionally accented by the frightened yelps of some unfortunate village dog that had snapped at the flock, incurring Tsopana’s ire. For an hour at midnight we were forced to halt and allow the animals a rest in the middle of the pavement between the high fences protecting the orchards lining both sides of the road, Bundled in our capes, we lay on the still warm asphalt, placing ourselves between the flocks and the few cars that might be travelling the roads at that hour.

After this short respite we were soon on our way—hoping to be out of the plain by sunup. Passing in the moonlight below the citadel of Mycenae, it was hard to avoid the image of a brooding Agamemnon, and at that hour it seemed as if little had changed since he gazed from its massive walls.

Dawn found us tired but relieved that we had traversed the plain without incident, and by late morning we arrived at our next camp. Here, in a small valley which supplies water from a large spring to the village of Fikti, we camped in the shelter offered by several large olive trees. The tension and unrest which had marked our earlier camps were replaced by joking and a sense of expectation as our thoughts turned mare to the high mountains whose first swell we had felt in our ascent from the plain. It was May 21st, the feast day of Saint Konstantine, and both Kostas and his maternal uncle celebrated their nameday as we slaughtered two young lambs and roasted them over the open fire. After the heat had subsided it was still necessary to graze the sheep and goats. Although the valley is over two hours’ walk from the nearest village and provides a regular resting ground for flocks on migration, this year a farmer had planted a small plot of vines on the southern face of the valley. Nikos raged against the foolishness of such a man. In fact, that vineyard symbolized an increasing problem for families specializing in herding, To avoid damage to the vineyard it was necessary for us to employ two shepherds in that valley rather than the single herder used in earlier years, Several ill-placed olive trees or vines can effectively ruin a very large expanse of pasture by requiring smaller flocks that can be controlled by the labor on hand. With the increasing use of the bulldozer in rural Greece, the days of work necessary to clear and terrace a favorable location on a mountain slope have been drastically reduced, leading to a significant problem for the future of pastoralism in Greece.

That evening we reached the plain of Nemea. Our camp was located under the steep cliffs which lodge the Monastery of the Virgin of the Rock. Under these sheer walls, for centuries, flocks on migration have found a resting place. When we arrived, seven flocks were crowded in the shadow of the cliffs, and the smoke of the women’s cheesemaking fires had begun to fill the air. From here the flocks would disperse to the north and west, following the worn paths to their individual summer pastures. That evening we visited Eleni’s brother’s camp, exchanging farewells and hopes for a prosperous summer.

By midnight we were moving through the endless rows of vines which make the plain of Nemea one of the richest vineyards of Greece. It was on this road the previous November that the driver of a heavy truck had failed to heed a shepherd’s faint warning light, and had run down a flock, killing over eighty sheep and leaving the pavement thick in the dried blood which served every shepherd passing later as a harsh reminder of the hazards of the road. Nikos had approved when 1 brought with me a strong flashlight that could be focused in the eyes of oncoming drivers. Seeing the effect of this powerful light, he remarked that “the drivers slow down because they think that you might be a truck with just one light—they do not fear ‘meat’ as they do steel!”

Our next camp on the ridge separating Nemea from the upland basin of Psari gave us our first sight of the towering, snow-covered peaks of Ziria in the distance. Here our camp lay close to the gravel road linking the Nemea and Stymphalia basins, Several times in the course of the day an old truck would labor past us on the ridge and, accompanied by shouts of recognition and the honking of its horn, continue its journey. These trucks were loaded with sheep also headed for the moun tains. More than half of the flocks in Greece which seasonally migrate from highland to plain are now moved by truck. Although he recognizes the advantages of shipping his oil, wool and household goods, Nikos refuses to move his flock by truck. He argues that, although the sheep travel well by truck, goats confined in such a small, jolting space do damage to one another with their horns. But every year, as the road becomes more difficult to traverse, fewer flocks make the journey afoot.

By evening we were working our way down the precipitous cliffs enclosing the basin of Slymphalia, when suddenly an old man shouted up to us from a field below that it was impossible for us to camp there. Upon our reaching the base of the cliff, the man continued to harangue Nikos, who fixed him with a stony glare. A moment later, the local agricultural policeman strode up, greeting Nikos with a smile and a welcome. Telling the old man to calm himself, he ordered Nikos to keep his flock as close to the cliff face as possible. Nikos complied and we began milking. After the old man had left on his donkey, the agricultural guard joined us in our meal. He shared the news of other flocks that had passed and, rising to leave, told Nikos he could safely graze the old man’s field. As he left, Nikos handed him the fresh cheese Eleni had just made, and wished him a good summer. Tomorow evening, the guard would once again take up his station in this field, the old man would return, and the charade would be repeated, with the next flock owner delivering his tribute of white cheese. Shepherds pay these bribes along the route of their migration because they are powerless to oppose the agricultural police and the bureaucracy they represent.

Hurrying through the damp night air, we began to climb the eastern shoulder of Ziria by morning. Our tired and hungry animals moved along a narrow track between fields of beans and vetches, and crazed by their hunger tried to break for the green of these crops. With great effort we herded them on—racing along the column as animals broke rank, hurling stones, crooks and curses as loud as our hoarse throats would allow. Finally, we reached a stretch of fallow ground where we permitted the flock to graze slowly as we herded them along.

As we made the tortuous climb along a torrent which held the flow of melting snows, the tension returned. Nikos surveyed every rock, tree and bush with a careful eye. Along our route we had asked for information, but Nikos remained anxious concerning the condition of the pasture. As we neared the high valley where Nikos and Spyros keep their flocks for much of the summer, a faint smile crossed Nikos’ face, and when finally we looked down on the lush green of fresh grass, spotted with the soft whites of slow moving flocks of sheep, a weight was lifted from our hearts. Soon we would be below with all the friends and relatives who had not been seen for six months. On the far side of the valley we could see the but or konaki of Barba Iannis, an eighty-six year old grandfather who still herds his flock of one hundred and fifty sheep with the help of his eight orphaned grandchildren. It was good to know that Barba Iannis, dressed in his traditional kilt and turned up, hob-nailed shoes. was still here to entertain us with his stories of the “old days.”

Tonight we would sleep again beneath the stars, but tomorrow the konaki would be prepared by cutting fir boughs and laying them over the pole frame of the hut, with a covering of woven goat hair. The grass was good, and with luck the milk would be plentiful, and Eleni would be able to make enough cheese to offset some of the winter losses. Salt and other supplies would be brought up from the village, and we could take turns visiting the recently built house which Joanna had readied for us below. Eleni smiled and said of this house with its modern kitchen and bath, “That’s not my house. It belongs to Ioanna, she understands it. These mountains are my home.” It would be a good summer until November, when the chill of the coming snows would touch the taIl firs with frost, and Nikos and his flock, responding to the rhythms of their lives, would once again take to the thousand year road.