From April through August 1954, the National Geographic Society sponsored an expedition to Melville Island, Australia, led by Mr. C. P. Mountford of Australia, to study the art, myth, and ceremony of the Tiwi. Miss Goodale accompanied Mr. Mountford to gather material for her Ph.D. dissertation on the Tiwi objects for the University Museum. After the departure of the other members of the expedition, Miss Goodale remained on the island until December 1954 in order to complete her research. During the eight months she was there, she recorded four separate funeral ceremonies during which the Tiwi carved, painted, and set up around the graves the unique grave poles described in this story.

On Wednesday, September 29, 1954, I walked down the hill to the native camp and along the dirt road leading past the new school, the kitchen, “Ali’s” house, “Buffaloe’s” store, and started up the opposite slope. A small black body came running towards me and flung herself into my arms. This was “Patricia” and it was her father I had come to see. Together we approached their little iron house and “Paddy’s” Nonolu rose to relieve me of my burden and laughingly repeated his offer first made some months ago, “More better you take her along America. She no like us anymore.”

“You come to America with me, Patricia?” I asked the chubby-faced, curly-haired, two-year old, very dusty cherub. “Kwa” (yes), she replied. (This exchange was to go on until the last week of my stay on Melville Island when I got my final reply, “kalo”[no].)

“Paddy, I would love to take Patricia to America but I have come to see you today about another matter. You know I shall be leaving in a few months’ time, and that the museum in America where I work has asked me to collect spears, baskets, pandanus arm bands, dance clubs, stone axes, and all the things which the Tiwi make, so that they can put them where Americans can see them. Now I think they would also like to see some of the funeral poles, but these are only made for a funeral and are put up around the grave to stay forever. I can’t take them away from a grave. Do you think you could make me some little toy ones so that they could see what they are like?”

“You like more better big ones?” he asked.

“Of course,” I said, “proper ones would be much better.”

“Well, I get five, six boy. We make you proper big poles. You take them along America. By and by you maybe die. We make you proper Pukamani.”

“But to have a proper Pukamani, Paddy, all of you should come to America too. No one there knows how to dance and sing and make a proper Pukamani.”

“You bin teach them,” he said. “Maybe we come we get killed by Indians.”

“Oh Paddy,” I replied, “the Indians don’t make war any more. They are just like you. Some live on reservations. Some go to work in towns. Many go to school and some even go to college. The Western movies in Darwin are all stories from Palinari, the old days. You used to fight and kill white men and strangers when they first came to your country just as the Indians did, but that was all over a hundred or fifty years ago.”

“Well maybe we get too cold along America; more better you teach them how to sing and dance and we make poles for you. How many you want? How big?”

“That all depends on how big Mr. Hickey’s boat is, for he will have to take them from Snake Bay to Darwin. Then they will go on a big ship to America. We’ll ask Mr. Hickey how much room he has; then we will know how big and how many.”

A weed later the supply boat from Darwin chugged into Snake Bay on the north coast of Melville Island and landed at the Australian Government Settlement where approximately 180 members of the aboriginal inhabitants now live, go to school, run a sawmill, and have erected permanent community buildings and private dwelling shelters, where new members of the tribe are born and where the deceased members are buried. (Seven hundred more Tiwi now live at the Mission on the neighboring Bathurst Island, separated from Melville Island by a half mile of water and from Snake Bay by thirty miles of bush country.)

All normal work in the Settlement stopped as the boat tied up at the jetty and all hands turned to, to unload the bags of flour, sugar, tea, and cases of corned beef and canned milk to supplement the fish, crocodile, turtle, and wallaby meat which the Tiwi hunters manage to find in the nearby waters and bush. Also unloaded from the boat were such items as bolts of calico to be made into wrap-around skirts or bikini-like nagas, the everyday dress of men, women, and older children. Tobacco, knives, hatchets, mirrors, razor blades, white shorts, shirts and trousers and colorful print dresses, blankets and mosquito nets, were carried up to the storehouse, some to be distributed to the entire population, some to await purchase by individuals who had accumulated credit or had become lucky in cards and had won hard money.

Soon after the unloading, I received the information I needed from Mr. Hickey. My poles should not exceed fifteen feet in length nor be heavier than two men could handle. I added one more restriction when I repeated this information to Paddy Nonolu–the poles should not contain structural elements which would be likely to break in transit. Aside from these instructions, my contract was essentially the same as is made between the close relatives of a deceased Tiwi and those who are selected to carve and paint the poles to mark the grave.

I agreed to supply some of the excellent yellow ochre from the distant Imilu locality, which I had in my possession. This ochre is pure and strong and when it is oxidized in a fire becomes a deep red. The other ochres could be obtained close to the Snake Bay settlement and the artists could easily collect them themselves. I personally had no axe to give the workers, but the superintendent of the settlement acted in my behalf and lent the necessary tool. He also “undertook” my obligation to “feed” the workers, an obligation which is in fact no longer necessary in the settlement where all the natives are fed from the government stores. If we had been out in the bush, or if it had been in pre-settlement times, I would have had to hunt for the workers, who were otherwise engaged in working for me and could not hunt their own food. At times today during the preparations for the final grave-side rituals, the relatives will give their workers a token gift of food, perhaps some succulent crabs or a cup or tea. In my contract with Paddy Nonolu I also gave him to understand that I would pay each individual artist in whatever manner each wished, upon the completion of the poles. This too was in accord with the Tiwi custom.

I then selected the workers I wished to carve my poles; however, the basis for my selection was on the skill and past performance of each worker, for I wished to have exact copies of certain poles which I had seen carved during the past months. This method of selection was quite at odds with Tiwi custom and deserves some further discussion, for the selection of the pole cutters is perhaps the most significant factor in understanding the art of the poles themselves.

In the old days, the Tiwi were not congregated into heterogeneous government and mission settlements but divided into fairly autonomous communities each with a recognized boundary. Within each community there were some residents who were born there and some who had married into the community, although there was no absolute rule governing the choice of a spouse from within or without the community. But as among all Australian aboriginal tribes (and many native groups around the world), every individual is considered to be related to everyone else in the community, and indeed in the entire tribe. Some of these relatives are considered to be more “close up,” others to be “long-way,” in spite of the fact that they are called by the same term, in much the same way as we regard “cousins” in our own society. When a member of a community dies, he or she is immediately buried in the bush at some distance from the camp. All “close up” relatives in the community must attend the burial but may not actually dig the grave. This job is left to a particular group of residents who are considered to be in relationship the most “removed” from the deceased. These people are not related to the deceased through their mothers or fathers nor through marriage except in the most distant way.

The commissioning of the pole cutters takes place some months after the burial, at the conclusion of one of a series of preliminary songs and dances led by the eldest resident “close up” male relative of the deceased–the father, father’s brothers, eldest brother, or eldest son. The leader and the rest of the close kin nominate pole cutters from among that group of community residents who are most distantly related to the deceased, those who also acted as undertakers at the burial. Not all of these kin will be selected, but no one who is not of this kin group, except their wives, may cut poles for the deceased, because the grave area is strictly tabooed and out of bounds for everyone except this class of kin from the time following the burial until the final ceremony.

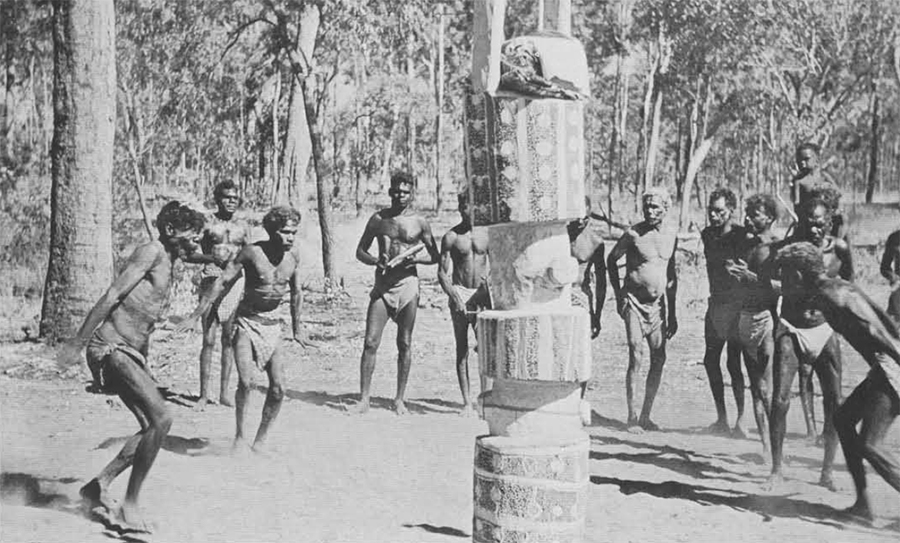

The leader commissions the workers by taking an axe and painting the handle white. He sets the axe in the center of the dance ring and the workers form a circle or semicircle around it and dance–no particular dance step, for although there are many different dance forms and steps. there is no “workers” dance. The leader then gives the workers their general instructions concerning approximately how many poles they should cut and how big they should be.

Thus we see that a Tiwi pole cutter is selected primarily because 1) he is a resident of the country i which the deceased is buried, 2)he is of a particular kinship relationship to the deceased. Only secondarily will the worker be selected on the basis of skill, and in many cases this is not taken into consideration at all. Every adult Tiwi is expected to be available for pole cutting (just as every adult American is expected to be available for jury duty). Although males are more often selected as workers, because of the physical labor involved, females may occasionally be commissioned, but usually they assist only as helpers to their commissioned husbands. The cutting and painting of poles is not the work of specialized artists, but an obligation which sooner or later everyone will expect to undertake.

Aside from the fact that each pole must end with a projection which will be planted in the ground, the ultimate shape of the pole will be limited only by the dimensions of the tree itself and by the imagination and skill of the individual artist. Likewise, the painted design is limited in the choice of color only, and that by the materials available, yellow. red and white ochre, and charcoal. There are no set styles of carving of painting, and although some individuals have developed a distinct style which will be repeated from contract to contract, each pole will often contain its own unique elements.

I have stated earlier that the selection of the workers on the basis of local residence and kin-relationship to the deceased is perhaps the most significant fact for the understanding of the art of the Tiwi funeral poles. The Tiwi themselves can identify the locality of a particular pole from the form and design alone and can sometimes even identify the individual artist. Although every pole in a particular locality is unique in itself, those of one area will exhibit elements which are lacking in another and will as a group be representative of a distinctive art style.

Since I had no contract with my workers for poles which would be set up around the grace of any deceased closer relative of mine, the area in which they chose to work was not tabooed to me as it would ordinarily be to the Tiwi employers. I often went out to sit quietly observing my employees, not because I had any desire to “oversee” their work, but to enjoy the feelings of peace and inspiration that come to anyone who watches a truly creative artist at work.

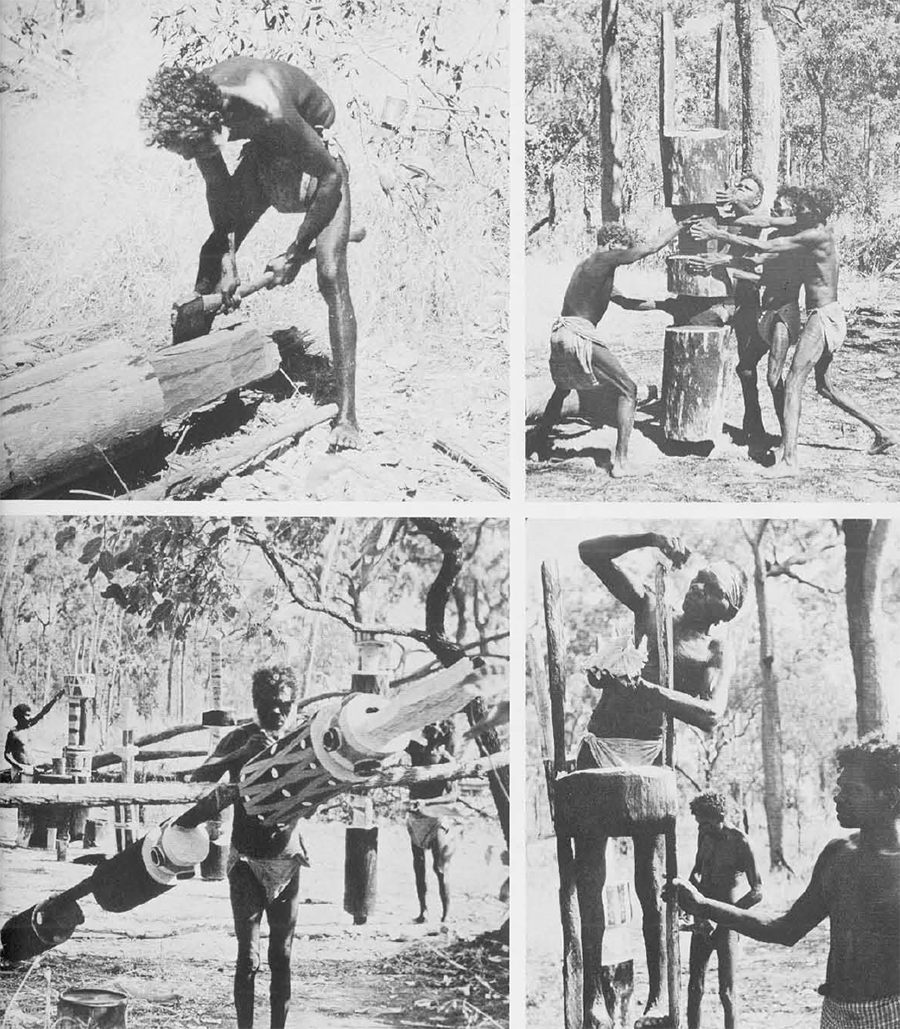

Each man selected his own bloodwood tree, the species most frequently used for a funeral pole because it is an extremely hard wood and best withstands the ravages of weather, insects, and time. The tree is felled, cut to dimension, and debarked. Then usually the pedestal is cut out at one end. By this time each man has fixed well in his mind the form which the pole will subsequently take and immediately begins shaping the wood, making hollowed-out sections (“windows”), knobby projections around the circumference (“breasts”), single or dual projections at the top (“masts” or “ears”), or other decorations which have no descriptive names.

The pole cutters worked slowly and carefully but without hesitation, knowing exactly what each blow of the axe would contribute to the form. Some worked with little relief; others paused to stretch their muscles, have a smoke, and chat, quite often voicing their next planned act of creation, but not for approval or advice either from the other workers or from their present employer. As the poles progressed, I noticed that, with one exception, they bore but faint resemblance to those each had carved before and which I had foolishly asked them to copy. Only that carved by the man who was considered by the settlement to be an expert, one who had developed a form which was quite unique in all aspects, carved for me, as he would for any Tiwi employer, a smaller copy of his usually very tall and beautiful pole. Most of the Tiwi artists appear never satisfied with a previous creation but feel that there is always room for improvement and innovation as they become increasingly skilled.

In about three days the poles were pronounced ready to be “cooked.” Cooking was a joint enterprise as, singly or in pairs, the fully carved poles were covered with dry brush and fired, and frequently turned so that the surface would be evenly smoked and blackened. This process not only dried the surface for the painting but also effectively created a black background against which the white, yellow, and red design would stand out in contrast.

The following day Paddy and the other men went hunting along the coast, collecting from the cliffs the white clay, and from the beach turtle eggs. On none of the other poles I had seen manufactured, had the Tiwi used turtle egg, but had rubbed the blackened poles before the design was laid on with the juice of orchid roots crushed in water. However, my workers said that turtle egg is the best and would hold the paint on the poles far longer and was the “proper old way.”

The painting of the poles took four days. Each artist cooked some of his own present of yellow ochre to make the deep red pigment, and crushed the charcoal and white clay and mixed them with water. Their palettes consisted of folded leaves, or paper bark, or tin cans; their brushes were small twigs chewed at one end. Dots they made with unchewed twigs, or with a piece of wood carved into a “comb” with which they could “mass produce” the dotted decoration. Some men finished one section of their pole completely before moving on to another, while others worked on their poles as a single unit, making the outlines of the design and then filling in with dots.

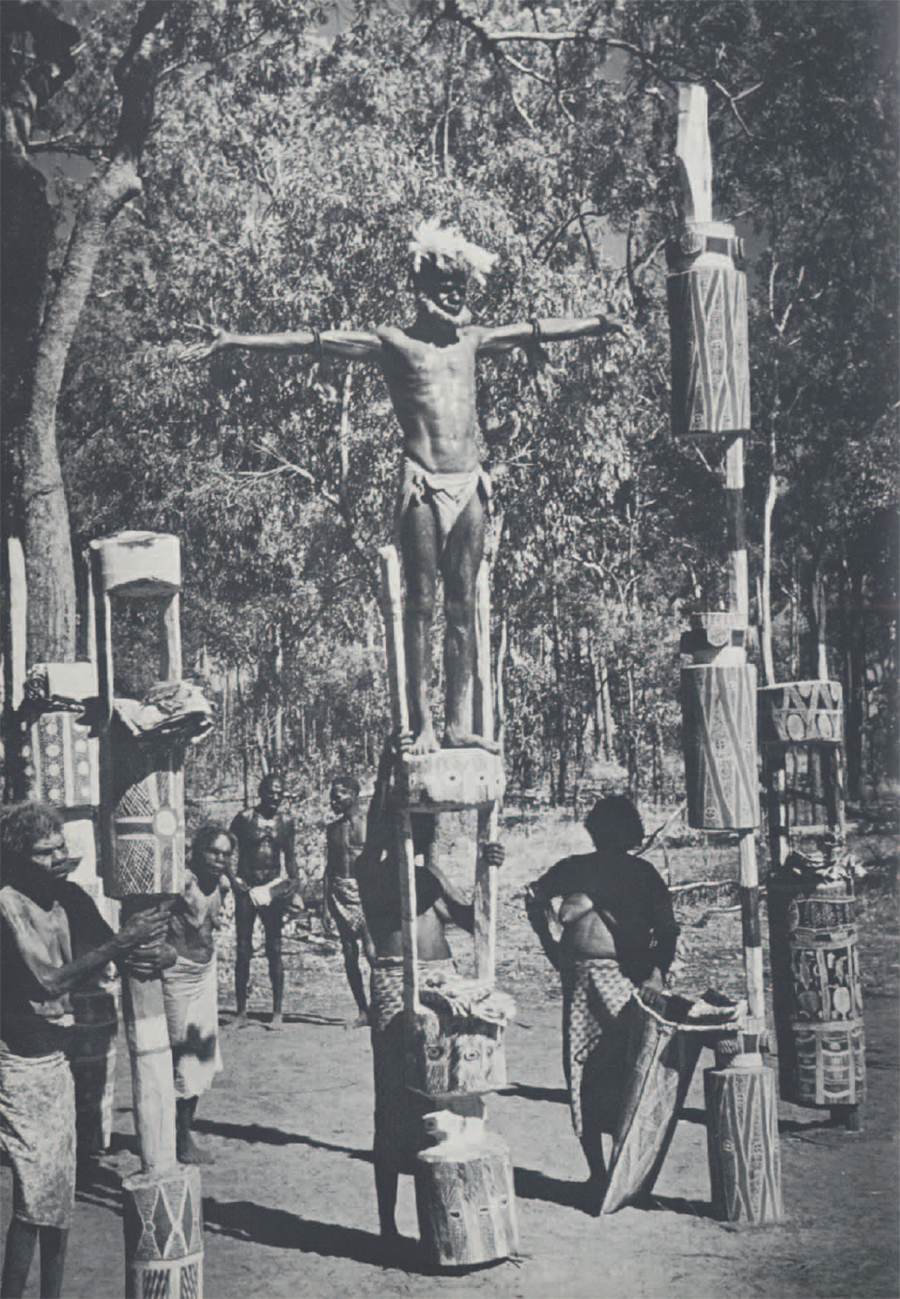

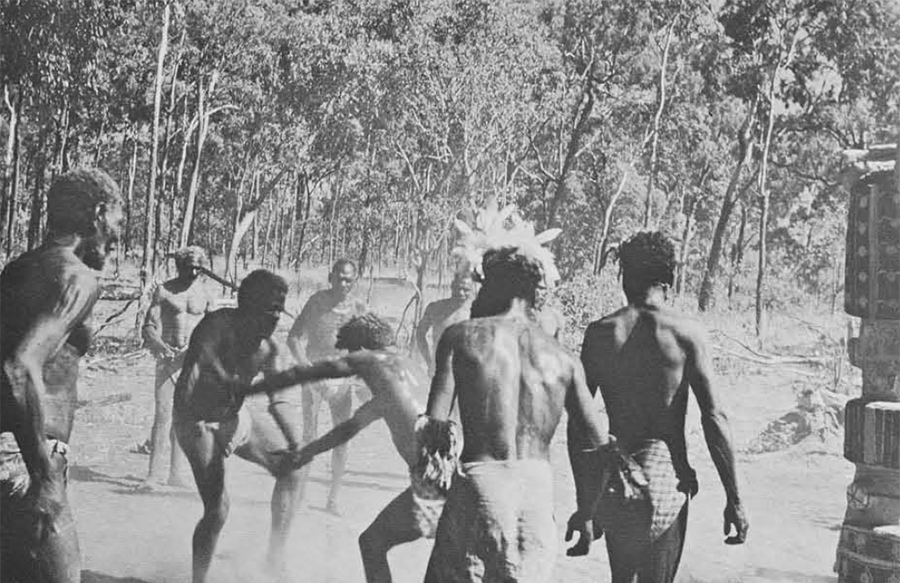

Finally my poles were finished and were moved to the settlement and set in the ground in a single row. Were I to have a proper Pukamani this would signify the beginning of the final ceremony. For such a ceremony the poles are set up in rows about fifty yards from the grave mound and the ground around the poles, and between the poles and the grave, cleared of all sticks and stones which might injure the barefooted dancers. The employers are now informed that all is ready at the grave.

Early in the morning everyone gathers and marches together to an area close to, but out of sight of, the grave and the poles. They carry with them large bark baskets elaborately painted, a number of multibarbed wooden spears, and supplies of paint, as well as blanket rolls, mosquito nets, and a certain amount of food. They also carry with them the gifts with which they will pay off the workers during the ceremony.

Stopping in the selected area, out of sight of the grave, the leader begins a short dance, lighting a smoking fire around which stand the men, who listen to the leader’s words and slowly join him in chanting his song and slapping their buttocks in time to the beat. When the chorus of men are chanting strongly, the singer and perhaps his brother or wife dance around and through the smoke of the fire while the remaining women shuffle into the dance in opposition to the singing male chorus. One or two other men initiate a song and dance at the conclusion of the first, and eventually all have passed through the smoke, which gives them strength and protects them from broken bones.

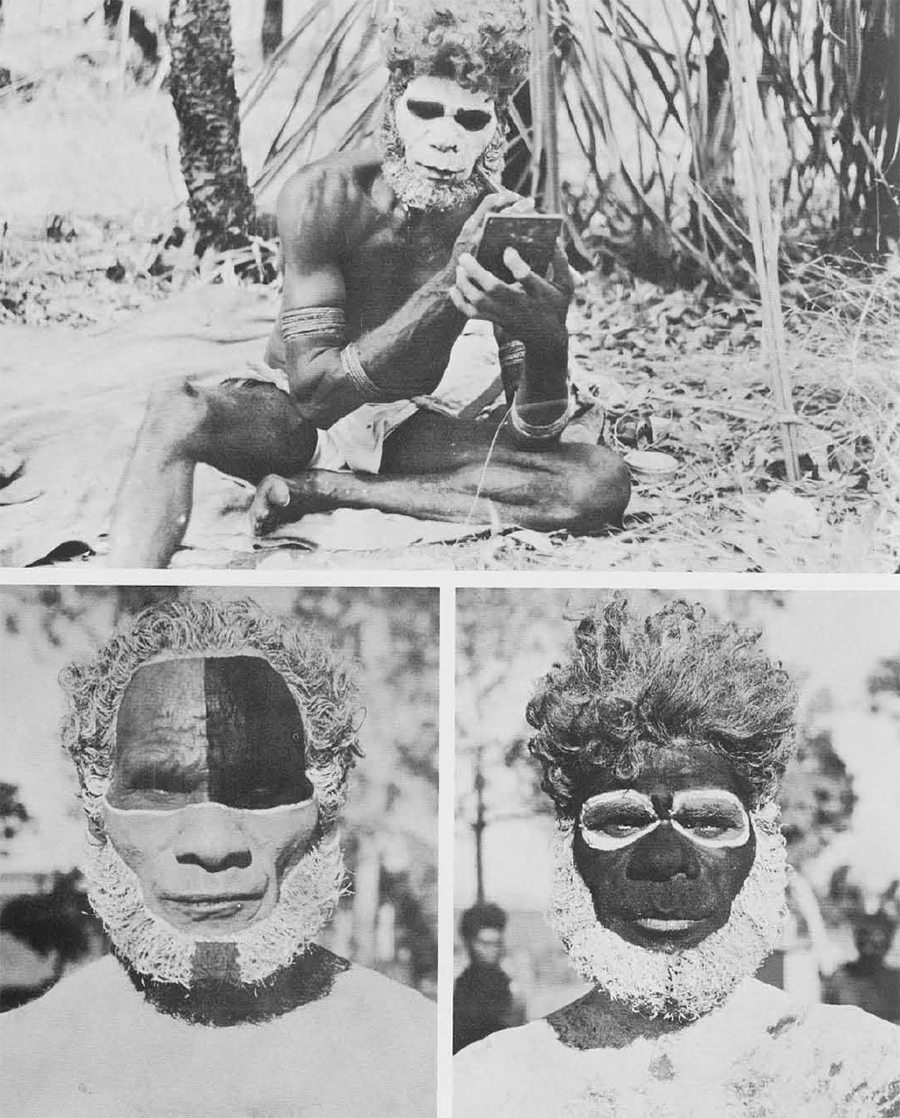

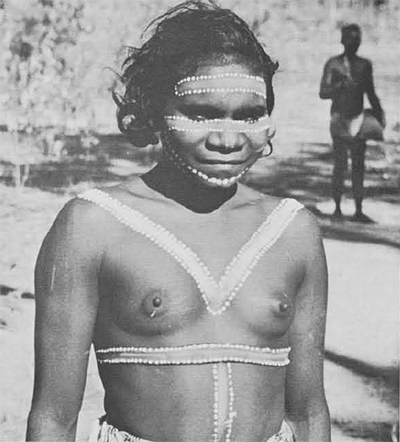

Each family now retires to its own little fire under its own shade tree and the painting of the body begins. The entire body must be painted including the hair and beard; and although much of this can be self executed, particularly if one has a mirror, help is often needed. Husbands paint their wives and are in turn painted by them. The pole cutters, however, do not paint themselves until all the close relatives are painted, for they have a duty to help anyone who needs their aid in this endeavor. Children should also be painted and they usually come last and perhaps have smeared enough paint on themselves to necessitate no additional attention.

The object of the painting is not to decorate and enhance the natural face and features of the body, but rather to obliterate them entirely, so that recognition on the part of the ghost of the deceased will be impossible. Of the various spiritual beings that share the Islands with the Tiwi, those of the deceased, the ghosts of the dead, are treated with the utmost respect at all times. Ghosts have been known to kidnap the living, carrying them off into the densest part of the bush and making them insensible and eventually killing them if they are not rescued in time. As ghosts do this mainly because of loneliness rather than for revenge, any close relative of the ghost is liable to be kidnapped, and thus all must take precautions. During the period of mourning following the death and burial until the close of the final ceremony many months later, all close relatives must paint their bodies in disguise and must never wash. They must wear braided pandanus bands around their arms. They must not touch any food with their hands nor any container of water. The many native names of the dead one, and even his English nickname, must never be mentioned by any living Tiwi for many years after the death, and sometimes forever, for the ghost remains always near the area of his grave, in the company of others who are buried in the area, hunting the animals in the bush and fishing in the rivers and sea. Nominally the land about the grave belongs to the ghost, but it may be hunted upon by his descendants for as long as his grave posts stand to mark his grave and his ownership.

During the final ceremony when the grave posts are placed around the grave and all the members of his local community and distant kin dance and sing, the ghost and his companion ghosts join the living to dance and sing, sometimes at the same time but most often when the living have finished a series, as during the night when all are camped close to the grave and again at the finish of the ceremony the following afternoon. It is because of the proximity of the ghost and his still intense loneliness that everyone must disguise himself before he approaches the grave itself.

Aside from the painting, false beards made of goose feathers and beeswax are tied around the chin, or over the head, of both men and women. Twisted human hair belts are worn around the waist or entwined into the head hair making an aboriginal “hair piece,” and cockatoo feathers set on wallaby bone pins are stuck into the hair.

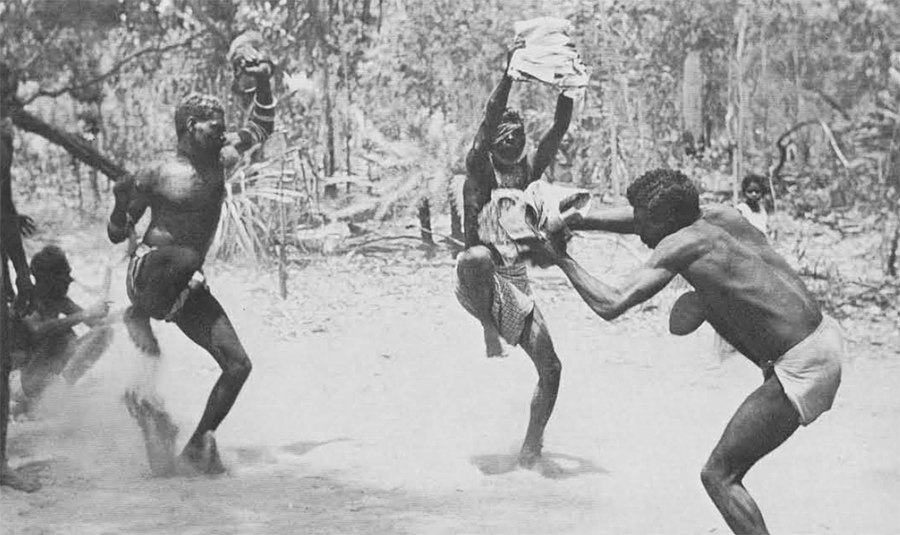

Late in the afternoon the elaborate body painting is completed and all gather from their family camps to march to the grave. One of the men starts a high shrill cry and others pick up the note, so that the sound is held for a long three or four minutes without diminishing in intensity until the grave comes in sight; then, dropping the “mosquito cry,” they rush en masse through the lines of poles and on to the brush-covered grave mound, wailing, shrieking, and crying, beating themselves on the back and head with clubs, and cutting their scalps with sharp hunting knives till the blood runs in small rivulets down the painted cheeks.

In about five minutes, the tide of grief abates, and all retire to the area close to the line of poles, and the singing and dancing begin again. As before, one man begins a song the words of which are slowly picked up by the semicircle of men as a chorus. To the chorus of clapping and chanting men, the singer steps into the circle and dances to his song, helped by his brothers, wives, and sisters. The dancing chorus of women forms the counterpart of the men’s singing chorus as they dance in unison their simple shuffling step, often accompanies by their very small daughters who learn to dance as soon as they can walk.

The songs which are sung are composed by the singer; most of them are new songs, but some old ones composed for other funerals. The tune is constant line, a plainsong-like chant, to which the words must be made to fit, often necessitating critical choice of words and license in the pronunciation and syllabification. The Tiwi singers are poets and composition of songs is one of the most important personal attributes that one can acquire. There are no song specialists, for every adult Tiwi is expected to compose at least one song for every funeral, and those who are in charge of the ceremony must compose as many as a dozen or more. A woman too composes special songs when her husband lies within the grave; there she sings during the final ceremonies as well as during the preceding months even when there is no audience.

The songs concern the past history of the tribe or of the individual who is now dead, current events in the settlement or recent news, mythological and fictional narratives concerning the animal, vegetable, and mineral environment of the island, or even movie-inspires stories concerning cowboys and Indians. Many of the dances serve to act out the action of the song. In many cases there are traditional dance steps which have been developed to mark certain subjects, such as crocodiles, sharks, birds, aeroplanes, buffaloes, turtles, boats, rain, frogs, bees, mythological spirits, radio, telephones, and flags and canoes, and many others. These steps are owned by their inventor and his descendants and when a song calls for a certain subject for which there is a dance, those who own the dance will enter the ring and illustrate the song, often helped by others who may not own the dance but have learned the intricate step. New dances are constantly being tried out on these occasions when a new song is introduced, and some may well become popular and traditional in the future. So, in the singing and dancing as well as in the carving and painting of the poles, we see the imagination and creativity of the Tiwi being held as an ideal.

Aside from the creative and illustrative dances there are those which certain groups of kin must dance. There is a mother’s dance, a father’s dance, a sibling dance, and a widower’s dance. These last two are far more frequently performed at an adult’s funeral, for brothers and sisters and husbands or wives are more important to an adult than are his mother or father and their sisters and brothers. The siblings of the dead one dance with an “injured” or “broken leg” because a muscle twitch in one’s leg means that some absent brother or sister is talking about you. The surviving spouses always dance with a fighting club, often throwing them at the finish of the dance into the bushes covering the grave, for they of all the relatives of the dead one must fight the hardest against the ghost.

Long past the setting of the sun, the dances continue in the flickering light of many small campfires burning in the surrounding bush. But as the night continues, the exhausted dancers drift away to their family campfires, finally leaving only the widows or widowers to sing their mournful wailing songs intermittently throughout the long night, as they walk slowly around between the poled and the grave keeping their vigil.

At daybreak the following morning the rested dancers begin again their rounds of songs and dances.

Along about mid-morning there is a change of pace. The gifts for the workers are brought into the dance area and the group of employers portion out the calico, knives, razors, shirts, shorts, tobacco, and so forth, to each pole according to its size. When all is ready they begin the “payoff.” This may take many forms. The leader of the ceremony may have thought out a special narrative dance which he now presents, or he may merely call each worker up and dance with the payment in his hands, handing it over to the worker at the conclusion of the dance. The worker must now dance with his payment in his hands to signify that he is satisfied with the amount and will allow his pole to be moved to the grave. (Should he not be satisfied, he will reuse to move his pole and it will remain forever apart, to rot alone on the dance ground.)

When each pole has been paid for and all the workers satisfied, they more the poles to the grave mound and set them up completely encircling the grave, and the bushes are removed from the mound exposing the bare reddish earth.

When all is set, the grave with its colorful and impressive markers is again rushed by the mass of mourners, wailing, shrieking, and beating themselves with knives and clubs. Some rush the poles headlong and are grabbed by others just before they crack their skulls against the hard wood. Then for the final time the Tiwi dance before the grave. During this dance the close relatives are washed and shaved for the first time since the burial, and their armbands are removed and placed on the mound. The large bark baskets are turned over the tops of several poles or left leaning against them, and the multibarbed spears are set upright between the poles. For the last time the mourners wail over the grave, hiding their heads among the poles before they drift off, turning back only to call out nimbangi, goodby, to the ghost of their kin.

The grave is now deserted. Soon the grass will creep in where the dancers’ feet churned the earth into fine dust. When the rains come they will wash the paint off the poles, and through the years the termites will make tunnels in the wood. But it will take many years for the wood to rot completely and for all trace of the grave to be obliterated by the forest. Anyone may now visit the grave, but one must always when leaving call out nimbangi to the ever-present ghost so that he will have no cause to follow.

When I left Melville Island in December I said nimbangi to all the ghosts as well as to the living Tiwi, but I cannot look at the poles which now rest in the Museum without feeling that I was followed by the Tiwi, who will always dance and sing for me beside the painted poles.