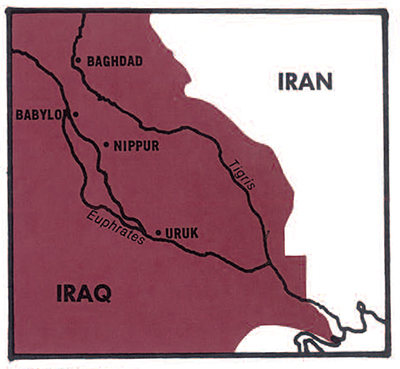

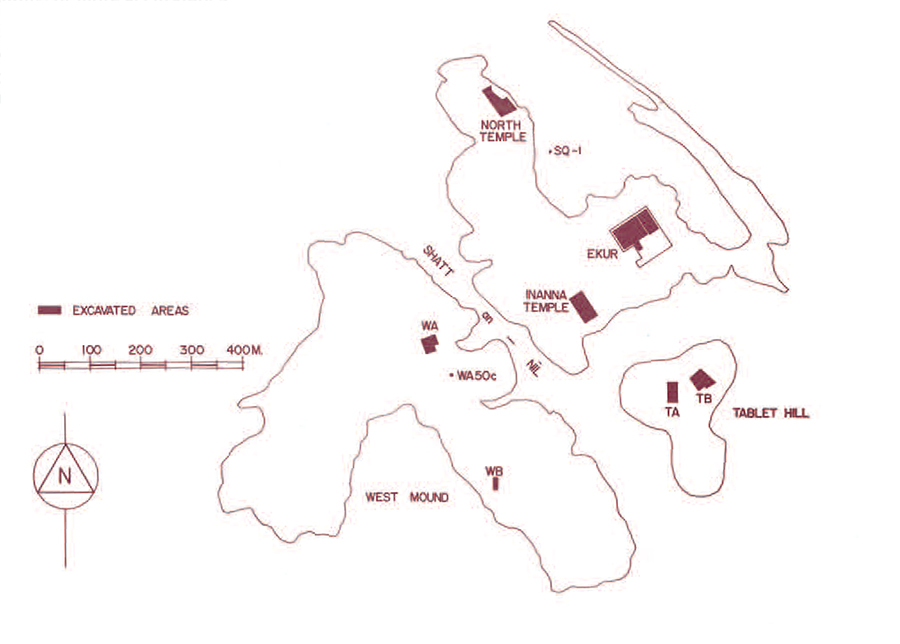

About the time a report on the eleventh season of the Oriental Institute’s expedition to Nippur was appearing in Expedition (Fall, 1973, pp. 9-14), the twelfth campaign was beginning. In the current seasons we are concentrating on the West Mound, a part of the city that has not been investigated since the University of Pennsylvania ceased digging here in 1900. During the eleventh season we began to expose in area WA a large nichedand-buttressed building, or more accurately a series of buildings superimposed on one another. In WB we exposed Old Babylonian houses, where there were many artifacts on a floor along with tablets dated to the reigns of Hammurabi and (18th century B.C.).

About the time a report on the eleventh season of the Oriental Institute’s expedition to Nippur was appearing in Expedition (Fall, 1973, pp. 9-14), the twelfth campaign was beginning. In the current seasons we are concentrating on the West Mound, a part of the city that has not been investigated since the University of Pennsylvania ceased digging here in 1900. During the eleventh season we began to expose in area WA a large nichedand-buttressed building, or more accurately a series of buildings superimposed on one another. In WB we exposed Old Babylonian houses, where there were many artifacts on a floor along with tablets dated to the reigns of Hammurabi and (18th century B.C.).

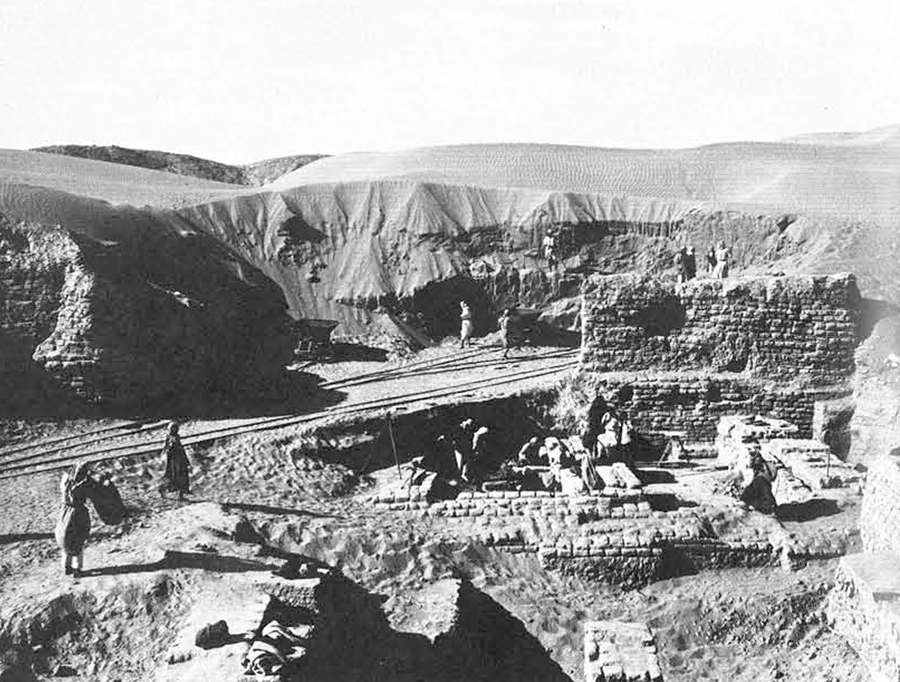

On resuming work in September, 1973, our first problem was the removal of the large sand dune that lay over most of the niched-and-buttressed buildings in WA. Road-building in the Nippur area made it difficult to find a machine to rent for this task, so we attacked the sand with shovels and hand-pushed railroad cars. As we proceeded we found that we were following a large trench made by Pennsylvania in the 1890’s, and that the meters of post-Neo-Babylonian material we expected to find had been cut away. The old excavations had come in right over the Neo-Babylonian building, but had hardly touched it. Builders in the Seleucid Period (c. 200 B.C.), however, had done much damage to the Neo-Babylonian level. In order to lay the foundation for their high wall shown at the right in the photograph, a large pit had been dug through part of the Neo-Babylonian structure. In the Seleucid fill we found several bits of iron pins that seem to have been from foundation deposits of the older level.

During our three months of work we were able to expose all or part of eight rooms in the Neo-Babylonian building. There had been two fires in the history of the structure, and we found remains of charred roof beams in the debris. Scorched plaster from the first fire was discovered behind a newer plaster that was in turn burned. Given the fires, we expected many artifacts from this level, but there were only a few beads, some copper crescents, and a few potsherds.

Below the Neo-Babylonian level we encountered a meter of mud-brick fragments which had resulted from the knocking down of the Kassite (c. 1300 B.C.) building below. This earlier construction, as far as we have been able to expose it, is different in plan from the Neo-Babylonian building, and is somewhat similar to the Kassite Ningal temple at Ur. In this level we again found few objects, due to an unfinished attempt at reconstruction. The floors of the building had been cleared and a platform of mud bricks laid down in the rooms. Then the inner faces of all the walls were cut back about thirty centimeters in order to leave enough room for the insertion of a new veneer one brick wide. But the veneer was never added. On the outside of the building a new face was constructed following the lines of the older face. We can date the original by potsherds and by an unusual seal impression that shows characteristic Kassite elements such as stars and lozenges, along with foxes, which are not common on seals. Under the Kassite building we encountered extensive pits with many layers of ash. Among the ash layers were found several whole pottery vessels and dozens of tablet fragments. The pottery seems to be a mixture of Kassite and Old Babylonian shapes, but the tablets are all round school texts, the product of schoolboy exercises datable to the Kassite Period.

The ash pits covered, and partially cut into, an earlier building of Old Babylonian date (c. 1800). The Old Babylonian building is rather poorly constructed and is, in fact, a renovation of an Isin-Larsa (perhaps about 2000 B.C.) building. For this report we will treat these two constructions as one building. It was from this level that we recovered, in the eleventh season, four cylinder seals and a broken stone axe with an inscription that led us to propose that the building and its successors were temples. This season, working in a limited area, we exposed parts of four rooms and a courtyard that yielded many objects. All the rooms showed signs of heavy burning. In the northern room, in a doorsocket, was a cache of bronze ornaments and two stone cylinder seals.

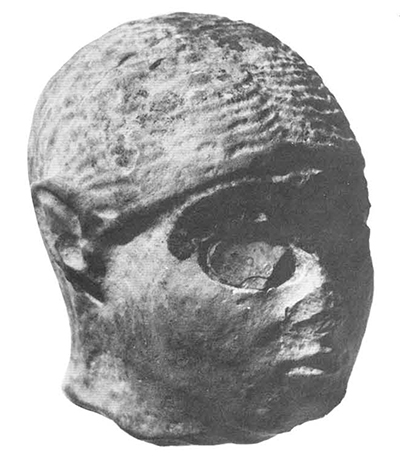

The rectangular room to the southeast is the one in which we discovered the seals and the axe in the eleventh season. This season five more cylinder seals were discovered here, along with four bronze crescents, a bronze star covered with gold foil, a bronze dog, a baked clay figurine of a tambourine player, beads of various sorts, and the head from a stone statue. The richness of objects in this room, plus unusual features such as a stone-laid platform and the recessed entrance into the room, give weight to the term “shrine.” The baked brick pavement outside the doorway, at the edge of what must have been an open courtyard, also emphasizes the importance of this room. In the debris from the courtyard we found a piece of a large baked clay foot.

In the room to the west of the courtyard the charcoal and ash-covered floor was strewn with more than a hundred beads of carnelian, agate, lapis lazuli, shell, silver, and gold. There were also a bronze dagger blade, a cylinder seal of Akkadian date (c. 2300 B.C.), and fragments of two stone vessels. On one of these fragments was an inscription. dedicating the object to the god Nin-Shubur for the life of Ibbi-Sin, the last king of the Ur III Dynasty (c. 2200 B.C.). This find does not necessarily indicate that the building is Nin Shubur’s temple, since the stone axe found the previous season was dedicated to a deity whose name, although it does begin with Nin, cannot be Nin-Shubur. The remnants of the signs do not allow such a reading. We therefore have a building with objects dedicated to two different deities. It is possible that the temple belonged to some other god entirely, and that these objects, some of which are hundreds of years older than the building, were merely being stored here as treasure, or were to be re-cut and re-used for that god.

It is also possible that we have uncovered two minor shrines in the temple of a major god. Temples often had several shrines in them. Until we can expose much more of this level and find inscribed doorsockets or foundation deposits, or tablets, we cannot say for certain whose temple this was. In fact, until that time we cannot even rule out the possibility that the structure could have been a secular administrative building, although the possibility seems less and less likely.

Outside the temple, in an Achaemenid or early Seleucid level (c. 400-275 B.C.) there was found a frit wedjat-eye and an unbaked clay plaque that indicate contact with Egypt, just as an amulet did in the eleventh season.

In our other area of work, WB, near the southern end of the West Mound, there were many pleasant surprises this season. In expanding operations both east and west we found that trenches and tunnels from the past century had not destroyed the levels above the Old Babylonian buildings as completely as we thought. In the top strata of debris were bits of wall that could not be dated precisely. Under one of these was a burial in a large pottery jar. The burial was in the baulk of the trench made in the eleventh season. A workman, seeking a shady spot to eat his lunch, brushed the baulk near the jar and tablet fragments fell out. These were the first indications of a hoard of one hundred thirty-nine letters, accounts, and lexical and literary tablets thrown around the jar as fill sometime about 700 B.C. These texts seem to be the archive of an administrator who dealt with irrigation, agriculture, the movement of troops, trade with Elam in Iran, and other matters. The tablets are in a slightly unfamiliar script, and give unusual values for certain signs. They are important not only for lexical or philological reasons, but especially because they help to fill a gap of several centuries before the Neo-Babylonian Period. We have little documentation for Babylonia during this time, and for part of the period do not even know who was the king or what relationship Babylonia had with the Assyrians, then in the ascendant. Dr. Robert D. Biggs has agreed to study and publish these tablets.

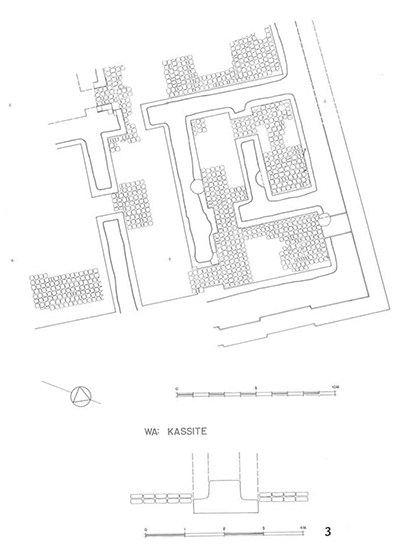

Below the level of the burial, Miss Judith A. Franke, who supervised WB, was able to discriminate enough between pits and ancient debris to establish part of the plan for a Kassite building of impressive proportions. From a courtyard paved with baked bricks a doorway led into two ranges of long rooms. A doorsocket at the south end of the exposure indicates at least one more range of rooms. If this building follows the plan of a palace known from Dur Kurigalzu, the Kassite capital near modern Bagdad, we should find a courtyard farther south. In fact, we might find several courtyards surrounded by ranges of rooms. Whether we are able to recover much more of the plan is somewhat doubtful, since natural erosion and old excavations have combined to remove much of the building. It is clearly a palace not only from its plan and size, but also from the evidence of more than a hundred fragments of Kassite administrative tablets dealing with oil, grain, and other commodities. Some of the fragments are dated to the reigns of Kudur-Enlil and ShagaraktiShuriash (mid-13th century B.C.). These tablets are similar to hundreds of texts found by Pennsylvania in the 1890’s which are being studied by Dr. J. A. Brinkman. Our work may localize the findspot of his documents.

Below the Kassite level the Old Babylonian structures found in the last season were almost completely exposed. To the north is the baked-brick building in which many artifacts and tablets of the time of Hammurabi and Samsuiluna were found in the eleventh season. This structure proved to have been somewhat later than the large mud-brick building south of it, but both houses were abandoned about the same time. The mud-brick building was well laid out and somewhat larger than the average Old Babylonian house. It was built on a foundation of almost two meters’ depth. Outside this house was a large area of ash layers four meters deep and more than twelve meters square. Among the ash layers were several bread ovens. Both the baked-brick and the mud-brick buildings are unusual, and the ash layers point to long-term accumulation from the making of bread. This area is the special province of Miss Franke, and I will not discuss further its significance other than to mention that several of the tablets found in the baked-brick house last season were concerned with the receipt of barley and the disbursement of large amounts of bread to various kinds of workmen including two hundred fifty men digging a canal.

The pottery that we are recovering from the WB buildings, along with grindstones and other tools, points to a utilitarian function. We are finding many whole and fragmentary pottery vessels and have begun to establish a sequence of Isin-Larsa through Old Babylonian types. We also have a group of pottery that is transitional to the Kassite. This transition is much needed to establish firmly the sequence in the second millennium. There are some interesting differences between the pottery from this area and that from Old Babylonian and Kassite levels in WA. In both areas we have been taking numerous soil and other samples to give indications of environment, fauna, flora, and function of rooms. These samples are being analyzed by various scientists but results are not yet in.

There was a fortuitous find from the surface this season. Our cook, Abbas Ali Dost, while walking out to visit WA, found a hoard of Islamic silver dirhems at the topmost point of the mound. These coins, originally in a cloth sheath, were from about A.D. 680 to 800 and must have been buried some time around the latter date. From the pottery at Nippur we have previously estimated that the city was abandoned sometime around A.D. 800. This find confirms our ceramic dating. There is a problem here, however, in that we know there was a Christian bishopric at Nippur until well into the tenth century A.D. It may be suggested that the name Nippur was at that time applied to one or all of a string of four low mounds northwest of the main mound, where slightly later pottery can be found. This suggestion could be verified by trenches in these outlying mounds.

- Hoard of tablets beside burial jar WB.

- Fragmentary baked clay foot from large statue. Found in courtyard of Isin-Larsa/Old Babylonian level in Wa. H. of fragment c. 12 cm.

- Fragment of stone vase with mention of Ibbi-Sin, last king of the Ur III dynasty. H. of ragment 10 cm.

- Unbaked clay plaque of Egyptian origin, found in Achaemenid/Seleucid context at WA. H. c. 5.6 cm.

- View of WB, northern end, taken from the southwest. HOgh wall abutted on left by layers of ash. Just beyond is baked-brick courtyard where tablets dating to Hammurabi were found.

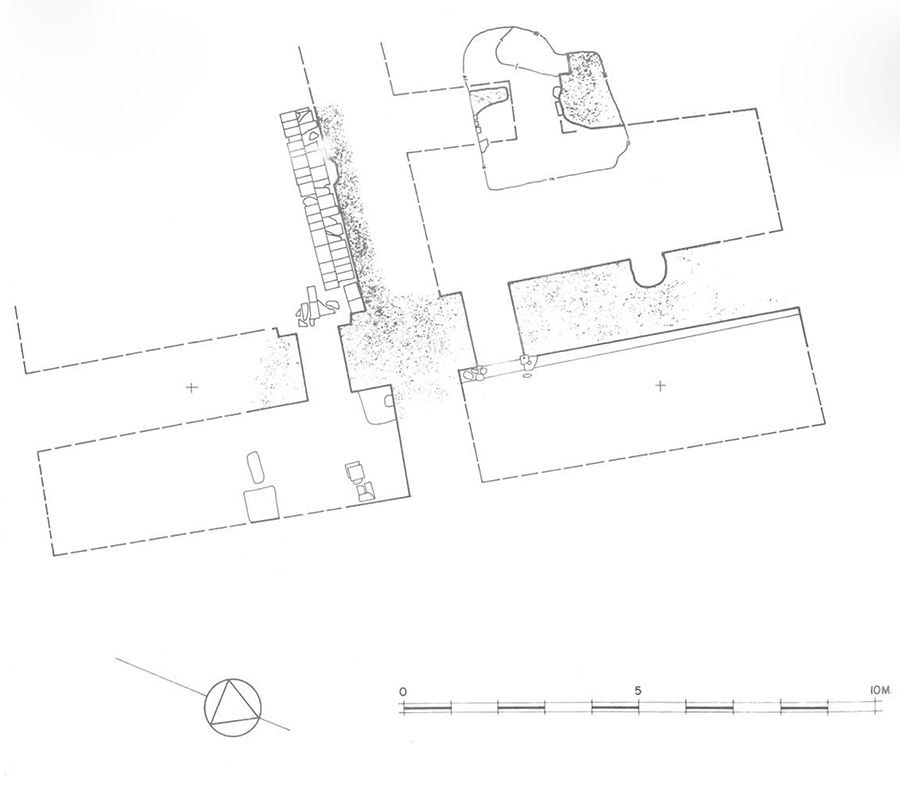

- Plan of badly disturbed Kassite palace in WB.

- Plan of Old Babylonian buildings in WB.

- Hoard of Islamic silver coins in a cloth sheath. From surface of West Mound.

We hope at some time in the future to take up such questions and elucidate the history of Nippur as a city through time mapping its largest extent, its declines, and its shifts of population or functional areas. In order to begin such investigations, we hope to make trial trenches in a low area southwest of the West Mound where air photographs indicate we may find part of the ancient city wall. We also, of course, expect to continue work in WA and WB, combining archaeology with information from the tablets and analyses of soil and other samples.

Our continued program of research depends on the generous assistance of the Iraqi Directorate General of Antiquities, especially of Dr. Isa Salman. We acknowledge our debt to him and his staff, in particular our representatives Mr. Riadh al-Qaissy and Mr. Abdul Kadir Shaykhly. We also owe a great deal to the continued support of the members of the Oriental Institute, above all a small group whose generous contributions made the season possible.