Tells el-Husn, ancient Beth Shari, was the first site to be excavated by The University Museum in what is today Israel. During a tour through British Mandate Palestine in the spring of 1919, Museum Director George Byron Gordon and Clarence Fisher, Curator of the Egyptian Section, chose Beth Shan partly because of its marvelous setting (Figs. 2, 3) at the eastern end of the Jezreel Valley, where it merges with the Jordan Valley. Set in the midst of fertile fields and shallow ponds teeming with fish and birds, Beth Shan had a perennial supply of water provided by the Wadi Jalud, the biblical Harod River.

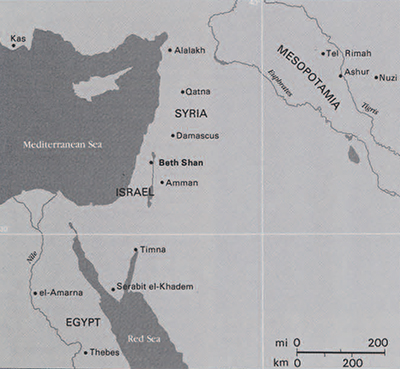

The site was clearly an artificial mound or “tell,” which had been built up over many millennia, and excavation there would not be impeded by any modern structures. Another reason for choosing Beth Shan was that the main land route between Egypt and Mesopotamia, two major centers of ancient civilization, passed by Beth Shan, with roads branching off north and south to ancient Damascus and Amman.

The excavations, which continued yearly through 1933, yielded rich remains of the Islamic, Roman, and Greek periods from the upper four levels of the tell. The most dramatic and unexpected discoveries, however, were found in the succeeding four lower levels (V through VIII). Numerous artifacts, Egyptian in style, began to be uncovered. Beth Shan is 250 km from the borders of Egypt and very far inland, over 50 km from the coast. Yet, the sheer quantity of Egyptian finds from the site has never been equalled at any other site in the region, even from extensively excavated locations closer to Egypt, along the southeastern Mediterranean coast.

The high point of Egyptian activity at Beth Shan occurred during the 13th century B.C. The largest collection of glass and faience jewelry from Late Bronze Age Palestine thus far found came from Levels VII and VIII. This hoard, including more than 1500 beads and 300 pendants from necklaces, and 40 vessels, had been deposited under a stairway of an Egyptian temple. Scientific and stylistic analyses of this collection, as detailed below, provide a rare glimpse of cultural, religious, and craft interaction between two diverse peoples.

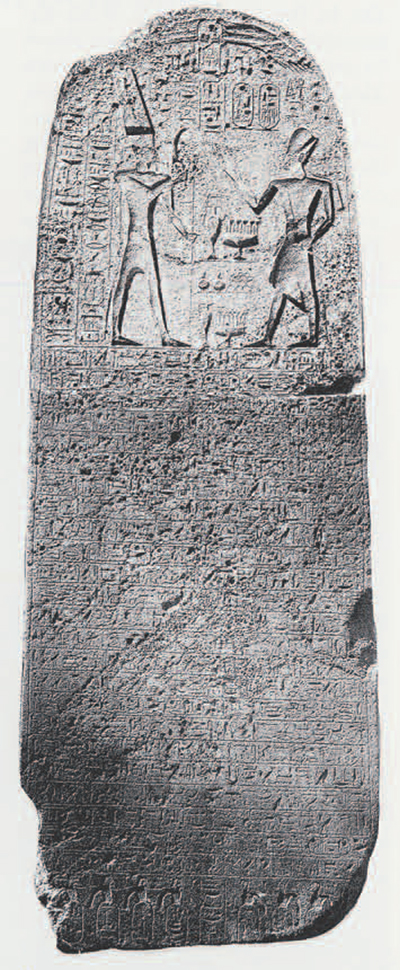

Two unique, complete monumental stelae of the New Kingdom Egyptian pharaoh Sety I and one of Ramesses II (Fig. 4) of the 19th Dynasty describe Egyptian activities in the area in the 13th century B.C., at the end of the Late Bronze Age. The Sely I stela, dedicated to the Egyptian high god Ra-Hamarchis, gives a detailed accounting of the military defense of Beth Shan and Rehob against the nearby belligerent city-states of Pella and Hamath, and against groups of marauding `apifu. This Egyptian word has been etymologically related to “Hebrew” by some scholars, who propose that the Israelite invasion is referred to here. Beth Shan is indeed described in the Bible as a stronghold of the Canaanites, the indigenous Semitic speaking people, that was taken by the Israelites only with great difficulty; the bodies of Saul, first king of Israel, and of his three sons were hung from the walls of the town after the Israelite defeat at nearby Mount Gilboa (see Joshua 17:11, Judges 1:27, and I Samuel 31:10-12). But the etymology of ‘apiru is debatable. Although the term could have included the early Hebrews, it is most likely a general appellation for any dispossessed people, who often took to banditry.

As part of the Egyptian expansion into western Asia in the 13th and 12th centuries B.C., Sety I converted the Canaanite city of Beth Shan into a military garrison, which was later refurbished by Ramesses II and the 20th Dynasty ruler Ramesses III. A strong defensive bastion, the so-called Migdol (Fig. 5), was constructed on the southwestern side of the tell, and a structure known as the Commandant’s House was built to the north. The latter may well have been the local residence of the Egyptian garrison commander. The residential sector to the southeast was built according to standard Egyptian plan, with central hall residences along a perpendicular grid of north-south streets.

Cult and Temple

the pharaoh and his god, Amun-Ra.

Museum Object Number: 29-107-958

The most prominent feature of the new town was a temple precinct near the center of the settlement, which was in use over a period of 200 years (Rowe 1940 First constructed in Level VIII during the reign of Sety I, the temple proper (Fig. 6) comprises a lotus-columned inner courtyard and a stairway leading up to a back altar room. It is almost identical to mortuary chapels and sanctuaries at el-Amarna, the capital of the monotheistic pharaoh Akhenaten, and to temples at the workmen’s village of Deir el-Medineh near the southern capital of Thebes (Peet and Woolley 1923; Bruyère 1930, 1948).

Even though the Beth Shan temple was Egyptian in style, the artifacts recovered point to a merging of Egyptian and Canaanite cultic traditions. Dedicatory stelae of the principal Canaanite deities—Mekal, “the god, the lord of Beth Shan,” and Antit, the local equivalent of ‘Asbtarte-combine Egyptian and Canaanite motifs (Rowe 1930). Hathor, the Egyptian goddess of foreign countries and the “Lady of Turquoise,” also figured prominently in the cult, as she did at other Palestinian sites controlled by Egypt: Timna, the copper mining area in the Wadi Arabah, and Serabit el-Khadem, the turquoise mining center in the Sinai (Rothenberg 1972; Petrie 1906). Hathor is shown on a “clapper” or wand (Fig. 7), made from a hippopotamus tusk, that was found in the inner courtyard of the Beth Shan temple. She appears full-faced and cow-eared, wearing a spiraling wig, fluted crown, and multistringed collar or choker. The exact function of such wands is uncertain, but it is conjectured that a pair of them were clapped by priests above their heads in a dance festival to Hatbor (Davies and Gardiner 1915 Many other Egyptian artifacts were found in the temple, including pottery vessels described as “flower pots,” and “beer bottles” that were possibly employed in a bread and beer ritual (Holthoer 1977).

If the local Canaanites and resident Egyptians had no inherent difficulty in combining religious iconography and practice, then it should come as no surprise that their respective ceramic technologies might be merged together in various ways. For example, rather than importing Egyptian pottery, vessels were more expeditiously made of local clays, very likely by Canaanite craftworkers under Egyptian tutelage (and compulsion). The same workshops probably also continued to produce a large quantity of standard Palestinian vessels, but quality suffered as heavily tempered, low-fired wares characteristic of New Kingdom Egypt became the norm.

Jewelry for the Gods

The impact of Egyptian stylistic and technological traditions on local Canaanite practice is especially evident in the large hoard of glass and faience objects. The silicate jewelry and vessels (Figs. 1, 8-10) were buried below or in the vicinity of the stairway of the temple, leading up to the back altar room. The practice of burying special objects as ex voto or foundation deposits under walls, floors, and under the steps leading up to the sanctuary was a common Canaanite and Egyptian practice (Cerny 1954). Some of the objects probably played a direct role in the cult. For example, chalices and jars with lotus motifs (see Fig. 9), which are very prevalent in the Beth Shan group, were used to present food offerings to deities in New Kingdom Egypt (Nagel 1938). The masses of beads and pendants (Fig. 8) had most likely been strung together originally to form pectorals or necklaces. Jewelry donations to the gods, who were now all under Egyptian suzerainty, constituted a subtle form of Egyptian political control at Beth Shan.

The Egyptian pendant types found at Beth Shan fall into three categories: (1) mythologically significant fauna and flora (lotus, mandrake, cobra, and cat); (2) Egyptian deities, such as the bandy-legged dwarf Bes, the god of merri merit and dance; and (3) hieroglyphic signs representing important religious concepts—”life” (ankh), “stability” (dd), and “heart” (ib; Fig. 1). Pendants of Syro-Palestinian type, including a ram’s head (Fig. 10), seven-rayed star disk, and crescent with horns, were symbolic of Canaanite deities and religious ideas. Thus, beyond serving ornamental, economic, or political functions, the Beth Shan jewelry is religiously significant. It was the “ultimate attire,” whose symbolic import enjoined divine favor and protection for both the gods and humans.

Since both Canaanite and Egyptian deities are depicted wearing necklaces (see Fig. 7), perhaps the jewelry from under the Beth Shan temple steps once adorned a cult statue or a temple official. In Syria, the Qatna temple inventories for the moon goddess, Nikkal, catalogue an incredibly rich collection of jewelry that beautified her cult statue. Other temples in northern Mesopotamia—at Assur, Nuzi, Alalakh, and Tell al-Rimah —have also yielded large jewelry collections, as have many sites in Palestine. None of these sites, however, has produced an intact cult ‘statue. Since such statues were probably made of wood or other organic material, very likely they have totally disintegrated.

A Merging of Egyptian and Canaanite Technological Traditions

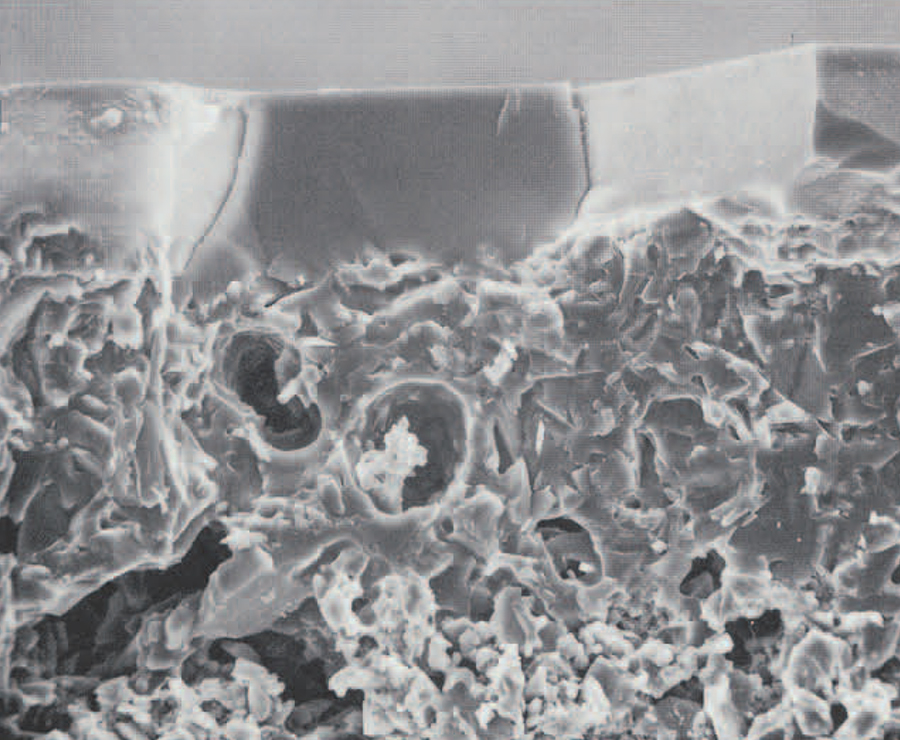

The glass and faience industry at Beth Shan had its roots in the early Middle Bronze Age, when glass was invented. But the Egyptian presence in Syria-Palestine in the late 2nd millennium B.C. brought changes to the industry. Just as we have seen for pottery manufacture, the Egyptians probably controlled the silicate industry at its most basic level: the preparation and supply of raw materials. Specifically, faience of standard New Kingdom type became very prevalent during the period of Egyptian occupation at Beth Shan (see Vandiver 1983). Egyptian faience was fired at lower temperatures than Syro-Palestinian faience, resulting in less glossy fusion of interior quartz particles (Fig. 11).

Compositional analysis has shown that colored glazes (e.g., lead antimonate yellow and cobalt blue; Fig. 1) were sometimes overlaid onto the low-fired surfaces of Beth Shan small faience artifacts (Fig. 11). These glazes had originated in the Syro-Palestinian glass industry. At the same time, the relative percentage of glass, which was less commonly used in Egypt, especially at sites in the Delta where many Canaanites lived, including craftworkers who were very likely responsible for the innovations (McGovern 1989).

Statistical evaluation of the compositional data reveals another important detail: the minor and trace elemental amounts associated with the glaze and glass corroborates of the small objects (beads and pendants) were significantly different from those large vessels made of these materials (McGovern 1989; Swann, McGovern, and Flemming 1989; Flemming et al. 1990). The minor elements associated with the vessels— elevated levels of lead and tin for calcium antimonate white cupric blue-green, and maganese-iron brown—are characteristic of silicate artifacts made in New Kingdom Egypt. Since the vessels are clearly Egyptian in style, the chemical data corrobates their manufacture in Egypt and importation into Beth Shan. Egytptian industries, such as that el-Amarna, excelled in the production of faience and core-formed glass vessels, which demanded considerable technical expertise.

On the other hand, the different chemical profile of the Beth Shan small silicate objects, whether of Canaanite of Egyptian type, points to local production of these objects. Silicate manufacture at Beth Shan would have been encouraged by the already established Canaanite industry, as well as by the probable arrival of Egyptian craftworkers at the site based on inscriptions (Cerny 1973:116; see McGovern 1989). The emergence of a synchretistic Egypto-Canaanite cult, with an increased demand for religious artifacts, would have further spurred the local industry.

Evidence of a local silicate industry was found in the southeastern residential sector (Fig. 5): a fragment of an Egyptian Blue frit colorant cake (Fig. 1) and rejected pieces of misshapen and overtired refuse glass and faience. The complete Egyptian Blue cake originally formed a flat disk about 8 cm in diameter, quite comparable in size and shape to contemporaneous examples from Egypt and, most recently, from the Kai shipwreck off the southern coast of Turkey (see Saleh et al. 1974; Bass 1986, 1987; Pulak 1988). Colorant cakes were transported throughout the ancient Near East, and local artisans could simply add specific amounts of the frit from this conveniently concentrated pigment source to glass or faience batch mixtures, or use the frit by itself, wetting and molding it to shape, and then firing.

Judging from what little is known about ancient silicate manufacturing installations, they need not have been very elaborate or complex (see Petrie 1894). A furnace capable of achieving about 900° to 1000° C, comparable to the temperature range used for well-fired Late Bronze Age pottery, is sufficient; in fact, silicate and pottery specialists might well have shared the same kiln. The necessary raw materials—silica, alkalis, lime, and many of the metals for colorants—were available in Israel and Jordan; those that were not, such as cobalt blue, which was probably processed in ancient Egypt and Iran, could have been imported (Kaczmarczyk 1986). The all-important prerequisite for local manufacture was the expertise to mix the materials in the right proportions, form the paste by hand or in a mold, possibly add a surface glaze, and then fire the artifact correctly. Molds could easily be prepared by pressing an existing pendant or other form into a ball of soft clay and hardening it. The mold for a fluted bead or inlay, shown in Figure 1, was found in the jewelry deposit under the temple steps. Possibly, it was considered an appropriate votive offering from a craftworker.

Conclusion

In attempting to understand the technological origins of the jewelry in the Beth Shan temple hoard, the paucity of written sources and archaeological data relating to Egyptian and Canaanite silicate industries per se is a serious limitation. For example, an important consideration about which little is known is whether Canaanite and Egyptian workshops were separate from one another, both in organizational control and output, with the former continuing to produce Palestinian objects as it had in the past, and the latter supplying Egyptian-style objects. In a broader sense, to what extent did Canaanites adopt or modify Egyptian culture, and Egyptians Canaanite culture? And how did this impact on the ceramic industries at the site?

The available evidence suggests that even if the two groups had separate workshops, the Egyptians were in control at the most basic level: the preparation and supply of raw materials (faience and heavily tempered clays). Given the physical and chemical properties of these materials, Canaanite ceramic specialists then appear to have adopted concomitant Egyptian techniques, including uniformly low-temperature firings of pottery and silicate artifacts.

Whether as a voluntary or forced response, change and innovation by indigenous craftworkers very likely took place for another reason. Canaanite craftworkers were situated in the middle of the civilized world and had long been exposed to different styles and technologies; as a result, they had the expertise to produce composite types. Egyptian society, by contrast, was generally insulated from foreign developments, and any Egyptian craftworkers at Beth Shan probably perpetuated the conservative technological traditions of their homeland.

Silicate production had all but ceased by the time the Egyptians withdrew from Beth Shan in the later Ramesside period (ca. 1100 B.C.). Yet, the local inhabitants maintained the outer form if not the substance of Egyptian tradition. The pharaonic monuments of Sety I, Ramesses II, and Harnesses III were prominently displayed in the courtyard of a Canaanite temple in Level V for at least another century, when the site was finally taken by Israelites and reduced to an insignificant village.

Glossary of Silicate Terms

ceramic: an inorganic nonmetallic material, which has been fired to a high temperature, including pottery, refractories, abrasives, cements, glass, ferroelectrics, etc.

Egyptian Blue: a frit (see below) that is comprised of hexagonal, platey crystals of copper calcium silicate, which give the material its distinctive coloration, and silica. Although first identified and described for Egyptian artifacts, it was made in many parts of the ancient Near East from an early period. The colorant was produced by heating (sintering) silica, lime, and a copper material (often bronze refuse) together. Small, flat circular cakes of the colorant were made and traded

faience: technically, a misnomer. The word is usually reserved for a tin-glazed earthenware potteryfrom Faenza, Italy, but has come to have a quite different, well-established meaning in the archaeological literature, where it refers to a silicate material that has a sintered or vitrified quartz body with a surface glaze. The glazing was accomplished historically in one of three ways: (1) by separately applying the glaze over the quartz body; (2) by mixing colorant and alkali (sodium and/or potassium salts) with the quartz body—the metal ions from the colorant and alkali will migrate (“effloresce”) to the surface during drying and form a glaze upon firing; or (3) by embedding the quartz body in a solid mass of colorant and alkali—upon firing, metal ions from the solid migrate (“cement”) into the quartz and form a surface glaze (see Vandiver 1983: fig. 23)

frit: a polycrystalline material, including quartz as a major constituent, that generally lacks a surface glaze. According to modern scientific usage, frits are silicate materials that are prepared separately from a glaze or glass batch mixture, and added to the latter. Egyptian Blue (above) exemplifies the ancient practice, which is quite comparable to modern processing

glass: a totally vitrified, amorphous silicate material, which is composed of a random network of silicate chains with interspersed metal ions (alkalis, alkaline earths, and/or colorants). Although composed of the same basic constituents (silica, alkalis, lime, and colorant) as faience, the higher relative percentage of alkalis in soda-lime glass enables the silica to fuse at lower firing temperatures

glaze: a glassy layer covering another ceramic material (e.g., faience or clay, an aluminosili-eate)

silicate: any ceramic material—e.g., faience, glass, or frit—that has silica or quartz as its principal constituent