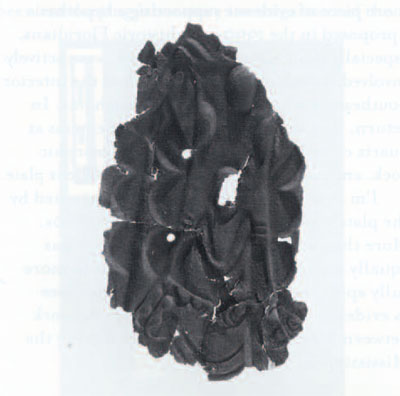

My heart raced when I first saw it. I was in the Museum’s collections area with American Section Assistant Keeper Bill Wierzbowski and South Florida Museum’s Curator of Collections Suzanne White. “It” was part of a copper plate, broken into four pieces. Green with the patina of age, the thin copper sheet had skillfully executed raised designs on it, clearly representing the lower half of a bird’s body.

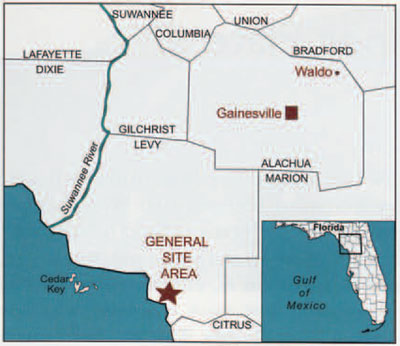

Funded by a Museum Loan Network grant, Suzanne and I were in Philadelphia to select artifacts for inclusion in a South Florida Museum exhibit celebrating the Philadelphia-Florida connection in archaeology and paleontology. The University of Pennsylvania Museum houses an impressive collection from the Mound Key site in southwest Florida, and it was during our examination of these artifacts that I noticed a flat cardboard box in one of the drawers. It contained the copper plate wrapped in tissue paper. When I pulled back the paper I immediately recognized the artifact as the lower half of a Mississippian Period repoussé copper plate, only a few of which are known from Florida. This one had been found in a mound 20 miles southeast of Cedar Key, an island town off the west coast of Florida.

The catalogue card indicated that it had been donated by Dr. George H. Ambrose and J. Willcox, and transferred from the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia in 1936 or 1937. I recognized the second name as Joseph Willcox (1829-1918), a Trustee of the Wagner Free Institute of Science who was also associated with the Academy. He traveled to Florida several times in the 1880s to collect paleontological, geological, zoological, and archaeological specimens. These were obtained through both field collection and purchase, and ended up in the collections of both the Academy and the Wagner Free Institute.

Dr. George H. Ambrose was a physician who settled in Waldo, Florida, around 1875 or 1880. In the late 19th century, Waldo was a prosperous town on the railroad that ran from Fernandina on the Atlantic coast to Cedar Key on the Gulf of Mexico. Besides practicing medicine, Ambrose was co-owner of a general store and served as Waldo’s postmaster.

A search of the Florida Site File turned up no record of a Mississippian Period mound (about AD 900-1600) on the mainland southeast of Cedar Key that might have yielded the copper plate, so we don’t know the exact site of its discovery. It is likely that Dr. Ambrose excavated or bought the plate in the area sometime in the early 1880s and sold it to Willcox on one of his trips to the region.

The copper plate portrays the lower part of a bird’s body, with portions of the legs, tail feathers, and wings. The feet have sharp talons at the end of each toe. Depictions of birds and humans with avian characteristics (or people dressed as birds) were common in Mississippian iconography throughout the Southeast and greater Mississippi Valley. The birds are typically raptors such as hawks or eagles. Because of the missing upper half, we cannot tell whether the plate depicts a bird, a bird/human hybrid, or a person dressed in bird regalia. Many archaeologists believe that some aspects of Mississippian religious beliefs and rituals were related to warriors or bird-warriors, perhaps mythical figures whose stories were widely known.

Although there were a few copper sources in Georgia and other parts of the Southeast, most of the raw material for these plates came from the Great Lakes region. Lacking smelting technology, metal workers cold-hammered copper nuggets into sheets, often skillfully riveting together several small sheets to form large gorgets or breastplates. They then embellished the plates with intricate designs, perhaps using carved wooden templates upon which the copper sheets were placed and then impressed with the design.

The hundreds of known copper plates show remarkable stylistic similarity; some found several states apart are nearly identical to one another. The design elements on the Willcox plate are the same ones found on eight copper plates found in Malden, Missouri, in 1906. Known as the Wulfing Plates, these artifacts depict raptorial birds. The lower portions of these plates include all of the elements present on the Willcox plate, suggesting they were made by a single artisan or group of artisans. Likewise, several specimens from the Spiro site in Oklahoma are also near duplicates of the Willcox plate.

The Willcox plate is one of a handful of Mississippian copper plates found along the west coast and inland area of central Florida. It is one more piece of evidence supporting a hypothesis I proposed in the 1990s: Prehistoric Floridians, especially those along the Gulf coast, were actively involved in trading marine shells into the interior Southeast, perhaps as far west as Oklahoma. In return, they were receiving such exotic items as quartz crystals, polished axes of metamorphic rock, and copper ornaments like the Willcox plate.

I’m sure that Dr. Ambrose was fascinated by the plate when he uncovered it in the 1880s. More than a century later, my discovery was equally exciting, but today we are able to more fully appreciate the significance of the piece as evidence of an extensive exchange network between Florida and the Southeast during the Mississippian Period.

Jeffrey M. Mitchem

Associate Archaeologist with the Arkansas Archeological Surveys and Associate Professor at the University of Arkansas