Any student of mythology knows that the many gods in the various religious pantheons of the world, as represented in sculptures, paintings, and manuscripts can be identified by their attributes, that is, by special symbols, articles of clothing, and objects carried in the hands. The science that concerns itself with the study of such attributes is called iconography or iconology; the knowledge (logos) of meanings to be attached to religious pictorial representations (icon). A lamb with a flag on a painting is a simple problem in Christian iconography, but many of the complicated allegories are now almost beyond interpretation.

Archaeologists and iconologists studying the remaining representations of the extremely complex pre-Columbian Mexican pantheon have even more difficulty in identifying specific Mexican gods than the iconographers working with Christian symbolism. This is true because there are few descriptions of these deities, and in many cases their attributes are missing. One of the iconographically better known gods of the pre-Columbian Mexican (Aztec and earlier) pantheons was Quetzalcoatl, the god of wind, of life, and of the morning; the god of the planet Venus, of twins, of monsters, etc. As the god of life, Quetzalcoatl appears as the constant benefactor of mankind. He discovered corn, and gave the grain to man. He taught man how to polish jade, how to weave, and how to do mosaic work with feathers. But above all he taught man science, thereby endowing him with the means to measure time and study the movements of the stars. He taught him how to arrange the calendar and devised ceremonies and fixed certain days for prayers and sacrifices. In short, Quetzalcoatl was the very essence of saintliness. His life of fasting and penitence his priestly character, and his benevolence toward his children–mankind–are evident in the material that has been preserved for us in the sixteenth century Spanish chronicles and in the picture writings of the indigenous manuscripts.

Alfonso Caso’s iconographical description of the god Quetzalcoatl, as he appears in a painting in the Codex Borbonicus–a pre-Columbian codex or picture writing book now in the library of the Chamber of Deputies in Paris–shows the complicated attire of this god, and the many attributes he carries, all of which have had to be analyzed and identified by the iconographer.

“The body and face of the god are painted black, since he was the pre-eminent priest and the originator of the self-sacrifice, which consisted of drawing blood from the ears and other parts of the body by pricking them with maguey spines and eagle or jaguar bone needles. Hence we see a bone in his headdress, from which hangs a green band terminating in a blue disk, the symbol of the chalchihiatl, the precious liquid, human blood. As further sacerdotal attributes, he carries in one hand an incense pot with a handle in the form of a serpent and in the other a bag of copal incense.”

“Covering his mouth there is a red mask in the form of a bird’s beak. This mask identifies him as the god of wind, in which form he was worshipped under the name of Ehecatl, meaning ‘wind.'”

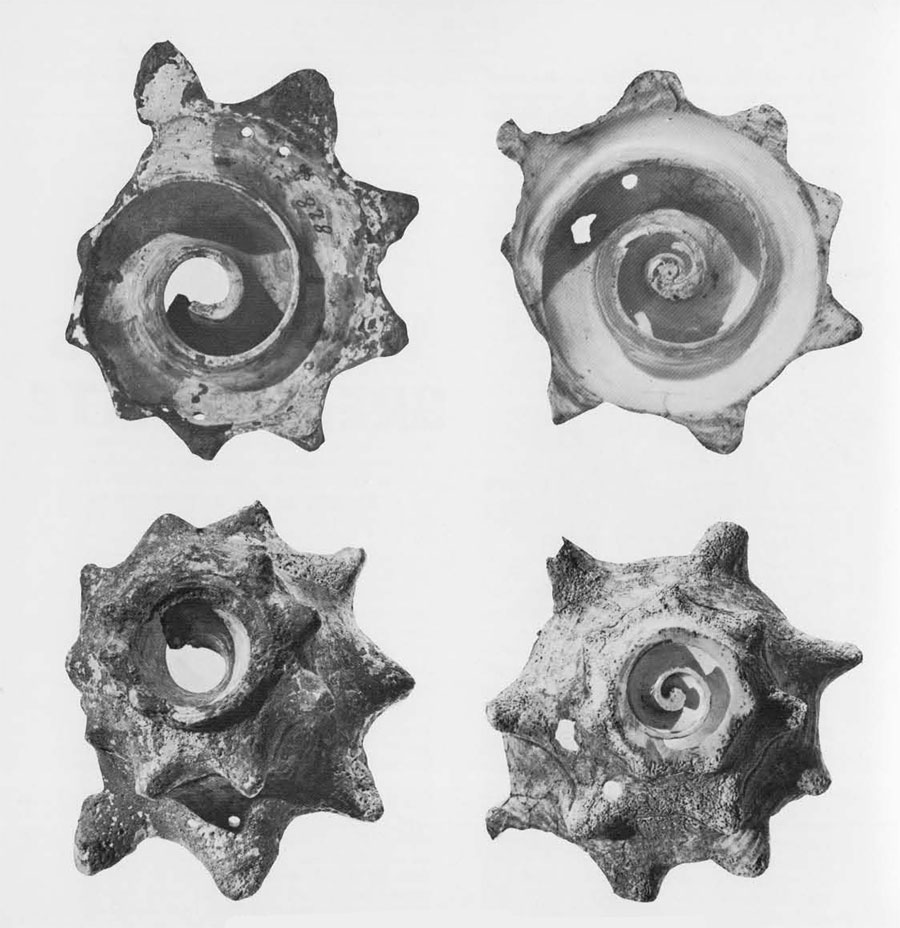

(Below) Back view of the unworked sections of the same shells.

“On his head he wears a conical cap made of ocelot (or jaguar) skin; it is tipped with a turquoise ornament and held in place by a tuft made of loops. The breastpiece edged with shells, the bracelets, and the ankle bands are likewise made of ocelot skin. His breastplate, called ehecailacacozcatl, or ‘breastplate of the wind,’ is formed by the transverse cut of a large sea shell, and his earplug is a turquoise disk from which hangs a red tassel and an object of twisted shell called epcololli, ‘twisted shell.'” (Quotations after Caso, 1958, “The Aztec: People of the Sun,” University of Oklahoma Press, pp. 21-23.)

What is of particular interest to us in this painting of Quetzalcoatl is the breastplate he is wearing. This breastplate, the insignia of the wind god, called in Nahuatl the ehecailacacozcatl, (the “spirally voluted wind jewel”) was made by cutting across the upper portion of a marine conch shell, and drilling holes for suspension by a cord. Such conch shell breastplates were either hung on the sculpture of the god himself or were worn by the high priests, the earthly representatives of this god. According to such sixteenth century Spanish authorities as Fray Bernardino de Sahagun, “the title of Quetzalcoatl was reserved for the high priests or pontiffs among the Aztecs and other inhabitants of Mexico. Only they were entitled to wear the emblem of ehecailacacozcatl, the insignia of this god. Such marine shell breastplates are therefore extremely rare. Of the few that survived the Spanish Conquest, most were destroyed by overly zealous friars; only a handful have been turned up by archaeologists. Understandably, the surviving few “spirally voluted wind jewel” breastplates are among the most highly prized possessions of the museums which house them.

The Milwaukee Public Museum is extremely fortunate in possessing one of these rare shell breastplates (Cat. No. 828), given it in 1900 by Mr. W.S. Wyman who obtained it in Mexico in the little town of Chalco. This town, located on the edge of Lake Chalco near Xochimilco, is today only a few miles southeast of the metropolis of Mexico City. When the “uncivilized” Tenochca-Aztecs arrived at nearby Lake Texococo around A.D. 1250, Chalco was already an important and flourishing Nahua city state For two hundred years the Chalcas and Xochimilcas successfully resisted the ever encroaching Aztecs. However, after various unsuccessful battles with such Aztec emperors as Itzcoatl (A.D. 1428-1440) and Moteczoma I (A.D. 1440-1469), the Chalcas finally gave up and about A.D. 1450 acknowledged Aztec supremacy. To commemorate their victory the Aztecs built a temple in Chalco and dedicated it to Quetzalcoatl. It is entirely possible that the shell “wind breastplate” now in the Milwaukee Public Museum actually hung on the breast of the high priest of Chalco during the dedication ceremonies of this temple.