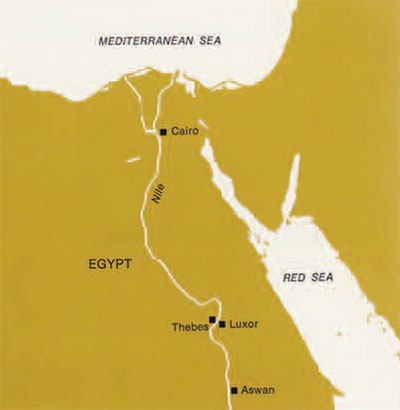

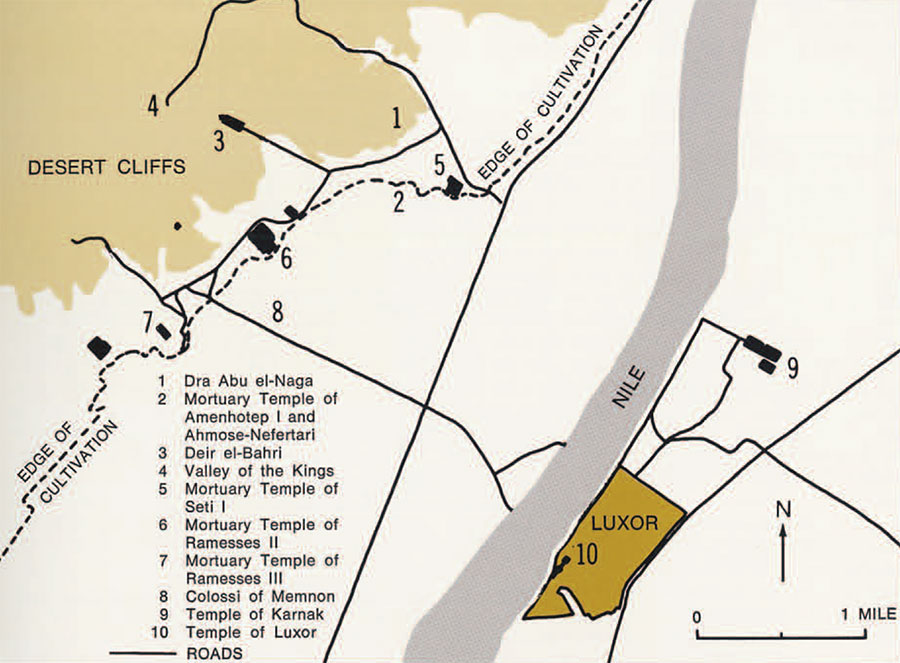

On the west bank of the Nile, across from the town of Luxor and the Great Temple of the god Amun at Karnak, lies the Theban Necropolis, stretching up from the cultivated fields into the desert cliffs which define the narrow river valley. Employed extensively by the ancient Egyptians from the New Kingdom through the Saite Period (Dynasties XVIII-XXVI, c. 1580-525 B.C.), this ground provided the burial place of Pharaohs and their Queens, and many important nobles.

On the west bank of the Nile, across from the town of Luxor and the Great Temple of the god Amun at Karnak, lies the Theban Necropolis, stretching up from the cultivated fields into the desert cliffs which define the narrow river valley. Employed extensively by the ancient Egyptians from the New Kingdom through the Saite Period (Dynasties XVIII-XXVI, c. 1580-525 B.C.), this ground provided the burial place of Pharaohs and their Queens, and many important nobles.

One of the cemeteries in this huge necropolis is known modernly by the Arabic name Dra Abu el-Naga. Located on the road between the Mortuary Temple of Queen Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri and the Valley of the Kings, this site first attracted the attention of an expedition from the University Museum during the two seasons 1921-23. Financed by the Eckley B. Coxe, Jr. Fund, and under the directorship of Clarence S. Fisher, then Curator of the Egyptian Section, the expedition undertook the excavation of twenty-two decorated tombs of officials, mostly Ramesside in date (Dynasties XIX-XX, c. 1314-1085 B.C.), as well as the ruined Mortuary Temple of Pharaoh Amenhotep I and Queen Ahmose-Nefertari (c. 1550 B.C.). Amenhotep and his mother Ahmose-Nefertari were deified after their deaths, and he became the patron saint of the workers who constructed the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings. The royal pair are also depicted in numerous private Theban tombs.

The work consisted of the clearance of the temple area and the tombs, and drawing up plans of them, recording of the decoration of their walls and ceilings, and recovery and recording of the burial goods and other objects associated with the ancient occupation of the site. The expedition returned from the field with photographs, hand-copies of the inscriptions, and drawings of the scenes in the tombs. Fisher published a preliminary account of the results in The Museum Journal, vol. 15 (1924), pp. 28-49; but the major publication was deferred. Work has continued over the years on the study and preparation of the records now stored in the Museum’s archives, but the excavation remains for the most part unpublished.

So the matter rested until the Fall of 1966, when a combination of favorable circumstances made possible the resumption of work on a more extensive basis. David O’Connor, recently appointed Assistant in the Egyptian Section, and intent on fulfilling the obligations previously undertaken by the Egyptian Section, wished to prepare existing excavation records for publication. At this same time Dr. Jaroslav Cerny was at the Museum as Visiting Curator in the Egyptian Section and Professor of Egyptology. As a philologist and epigrapher, who has long worked at Thebes and has a special concern for the Ramesside Period, Professor Cerny took an immediate interest in the proposed project at Dra Abu el-Naga. And I welcomed the opportunity to participate in the work. We expected material to emerge from the research which could be incorporated into a Ph.D. dissertation; and I would be able to do epigraphic field work and conduct philological investigations in Egypt under the best possible supervision. So the personnel of the project were organized: Professor Cerny the Adviser, David O’Connor the Principal Investigator, with me as Assistant Investigator.

The aim of the project is simple: to verify the excavation records and complete the documentation, to organize and study the evidence, and to translate and comment on the texts, so that publication can proceed as swiftly as possible.

It was decided first to concentrate on the decorated tombs. Besides representing a long-standing commitment of the Museum, the publication of the tombs would be of considerable Egyptological interest, and important results can be anticipated. Of approximately two hundred known decorated Ramesside tombs at Thebes, only about twenty have been published in detail. As major sources for the understanding of funeral and burial customs, religious beliefs, social structure, daily life, and architectural and artistic traditions, these tombs can be expected to contribute significantly to the study of the ancient Egyptians.

Moreover, considerable genealogical and historical information is to be found in the tombs. Their owners include three High Priests and several lesser officials of the god of the e Empire, Amun of Karnak, as well as two Viceroys of Kush and two of their Egyptian subordinates, military governors of the south lands, the conquered African provinces of the Empire. It is precisely in the later Ramesside Period that the power of the two offices of Viceroy of Kush and High Priest of Amun grew to rival that of the Pharaoh himself; and we hope to be able to illuminate the earlier stages of that development. One of the Viceroys, Anhotep, is known only from his tomb at Dra Abu el-Naga (No. 300). Of the tombs of the High Priests, one (No. 157) contains the text of his appointment in year 1 of Ramesses II. Another High Priest is Bekenkhons (No. 35). Egyptologists have not yet been able to agree on even how many High Priests there were named in Bekenkhons. We hope by this study to establish their identities and individualities, and thus also to help confirm the succession of the High Priests of Amun during the early Ramesside Period. In addition, by fixing the chronology of the tombs and the identities of the owners and their families, we will try to determine the burial patterns and reconstruct the history of this part of the necropolis.

Financed jointly through the Coxe Fund and a grant of PL 830480 (Counterpart) Funds, as administered under the Foreign Currency Program of the Office of International Activities of the Smithsonian Institution, the campaign got off to a rather halting start. Because of some missing papers, my departure was delayed for over a week, every day of which friends in the Museum bid me farewell, only to see me again the following morning. In the end they seemed surprised that I actually left. But eventually all the papers were ready, and I had a reservation. On the scheduled day of the flight out of Philadelphia, however, the airline called to advise me that weather conditions were unsatisfactory, and I should therefore take a train to New York to meet the flight. Of course, weather conditions were also unsettled at Kennedy, but after a wait of some five hours there, I finally boarded at about 1:00 on the morning of January 28.

The project had the benefit of the advice of Professor Ricardo A. Caminos of Brown University, an Egyptologist much experienced at epigraphic field work. He assisted in equipping the expedition and gave the addresses of various shops in Europe where quality drafting materials can be obtained in quantity for immediate delivery. And so in a small tailor’s shop near the British Museum in London, I obtained tissue paper for making rubbings of reliefs; and in a small paper shop near Karlskirche in Vienna, tracing paper and other essentials.

Arriving in Cairo on the night of February 13, I established contact with our friends in the American Research Center there and the American Embassy. The Embassy administers our Smithsonian grant in Egypt, and the staffs of both organizations were generally helpful in giving useful advice and rendering numerous services. After having undertaken the preliminary negotiations with the Antiquities Service, I flew to Luxor to join Professor Cerny, who was already at work there with the Center of Documentation, copying ancient graffiti in the Valley of the Kings. I had sent a sixty-pound suitcase, full of supplies, by air from Philadelphia to Cairo ahead of me. This I carried with me from Cairo to Luxor. The porters and airline officials were quite surprised when I arrived with a hundred pounds of personal luggage, considerably over the maximum allowance; but I paid the excess baggage charge, and arrived without further complication.

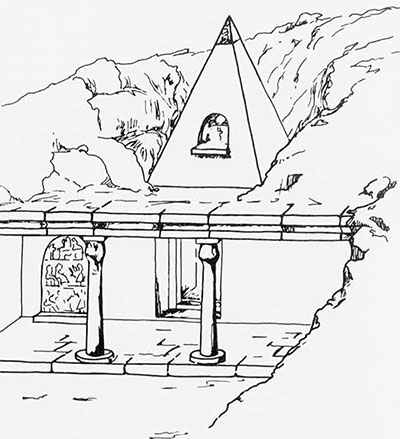

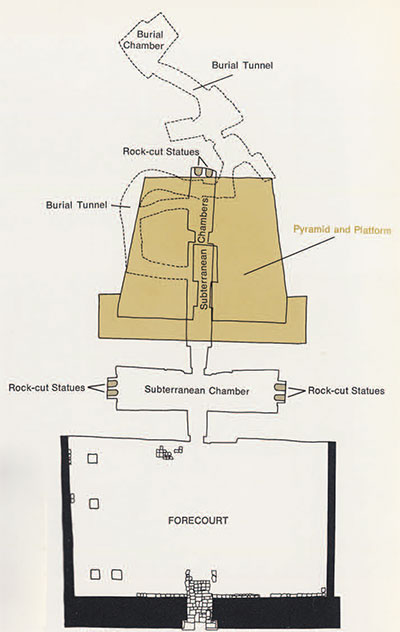

At Luxor I proceeded at once to the site. When newly furnished, the cemetery must have presented quite a spectacular appearance. One approached a tomb through the pylons placed at the front end of an enclosed forecourt, in which was erected the funerary stela, or gravestone, of the owner. The court was cut back into the face of the cliff, and the walls thus rough hewn were lined first with mud-brick, against which slabs of smoothly polished stone were later set. The floor of the court was paved with stone, and a colonnade ran around its edges. Above the court and behind it, situated on a platform built right on the rocky scarp, stood the mud-brick pyramid, capped by a stone pyramidion. Within the pyramid was a small chapel.

At the back of the court was the entrance to the tomb proper, leading into a series of rock-cut chambers, where funeral rituals were carried out and offerings were presented before the statues representing the deceased seated with his wife. These rooms were sometimes large enough to require pillars for the support of the roof, one of the largest of them being 86 feet by 20 feet. The height of the ceilings is up to about 12 feet, and the chambers may run back into the mountain as far as 100 feet. The statues are in one instance colossal ,being about 12 feet tall. Leading off from an inner room, a winding tunnel descends rather steeply down to the cavern which is the actual burial-chamber. There, in sarcophagi of red granite from the First Cataract Region at Aswan, were laid the deceased couple, in what was intended to be their mummies’ final resting place.

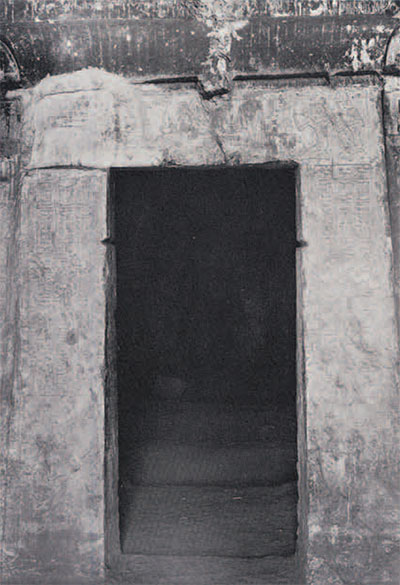

Brightly painted hieroglyphic inscriptions, scenes, and designs decorated all exposed surfaces, being drawn on the plaster of the exterior of the tomb complex as well as the walls and ceilings of the offering chambers and pyramid chapel, and incised on the stone walls of the forecourt and on the interior lintels and jambs. The hieroglyphs give the name and titles of the deceased and his family, and religious and funerary texts, accompanied by representations of offerings and depictions of the daily life of the deceased, and the funeral itself.

This was the original appearance of a tomb. Unhappily, however, the cemetery has endured much through the millennia since the Ramesside princes were buried there, in the typical pattern of burial: plunder of the tomb, human habitation of the forecourt and subterranean chambers, exploitation by antiquities hunters, excavation, and occupation of the opened tombs by bats. So the present appearance is considerably altered.

The site, lying within the Arab village of Dra Abul el-Naga, and behind the slopes above it, is not visible from along the road. One approaches it by climbing up through the village, which is built right on the ancient cemetery. Fisher believed that every house in the village marks the site of a tomb, the peasants simply building a mud-brick house in the forecourt, and incorporating the rock-cut chambers into the structure. I was shown one such dwelling during a preliminary examination of the site.

Other tombs, while not actually part of a house, are certainly located in the midst of the village. Several houses are built in the forecourt of one of them (No. 157), which is thus accessible only along a narrow alley. When we wished to visit this tomb, it was necessary for the Antiquities Service watchman to go ahead to drive away the local dogs, who always dart in and out, growling and snapping at any outsiders. When these animals had withdrawn to a safe distance, we could make our way to the entrance, past the villagers and their goats. Then the watchman would sweep back the debris which blocked the gate, so we could enter. Finally, after chasing out a stray chicken, we were ready to set to work, beset only by the small, harmless bats which inhabit the inner recesses of the tombs.

We had been warned to watch out for scorpions and the two poisonous snakes—the cobra and horned viper—and, indeed, it is necessary to exercise a certain amount of caution when entering a cool dark tomb, a likely haunt of theirs. But, fortunately, we encountered nothing more dangerous than flies, lizards, bats, and birds—any of which may constitute a considerable nuisance, but no real threat to personal safety. The flies are persistent, and rather annoying; the bats have a very unpleasant odor associated with them, and can create quite a distraction as they go fluttering about in the dark, occasionally bumping into one. And nothing is quite so unnerving as to enter a tomb cautiously, taking care not to fall into a shaft and not to tread on any cobra which might be there, and suddenly see something scurrying across the low ceiling just ahead. The heart nearly stops, until it is ascertained that this is merely a harmless lizard. Even a sparrow came regularly to one of the tombs to pick at the plaster, thereby destroying its decorated surface. It was thought best to attempt to discourage such behavior, particularly since having just heard the story—purported to be true—of a tomb whose decoration was entirely eaten by chickens searching for the lime used in its stuccoed walls.

The tombs have suffered extensive defacement and mutilation, both natural and human, unintentional and deliberate. Having been cut in stone of generally poor quality, there appeared at the time of their construction large cracks and faults, which needed to be repaired. This was done by filling them in with rocks and then plastering over the rough fill; or if possible, by squaring the holes and setting in carefully dressed limestone blocks with mortar. Walls and ceilings were plastered to cover any uneven surfaces, and, as mentioned above, the walls of the forecourt were lined with polished limestone.

In the course of time, plaster had flaked off and its decoration been smashed against the floor, patches have dropped out, and the limestone torn up from the court for re-use. Thus the construction of the tombs is revealed, but the decoration is destroyed, and surfaces are exposed which were intended to be covered. One tomb *No. 283) was hewn in such poor stone that the ceiling of one of its chambers had come crashing down, largely ruining the tomb.

As more and more tombs were constructed in an already crowded cemetery, architects’ mis-calculations occasionally resulted in part of an older tomb being destroyed, as the subterranean chambers of a new tomb were driven into a cliff. Robbers searching for treasure and, later, antiquities, did not hesitate to smash walls, looking for the hidden entrance to the burial chamber. And having thus gained entry to one tomb, these predators continued to break through to neighboring ones, ravaging and plundering as they went. There are miles of these robbers’ tunnels under the Theban Necropolis, resulting in its having been referred to as the Theban Labyrinth. It is possible to enter from one tomb and emerge from another, quite distant; or to become lost. I did not get lost, but once, in following such a tunnel for some short distance from one of our tombs, did suddenly find myself in an offering chamber of a nearby blocked-up tomb, inaccessible from the outside.

Other destruction seems to be the result of the labors of ardent iconoclasts, or wanton vandalism. Some parts of the walls were replastered, covering over the original decoration. This overlay is not normally objectionable; for it forms a protective coating, and when it has been removed, the earlier surface beneath it remains often better preserved than the surrounding wall. However, mud-dauber wasps have also built their concrete-like nests against the walls and, particularly, the ceilings; and they are very difficult to remove. In other places the paint has decayed so that the inscriptions are now illegible.

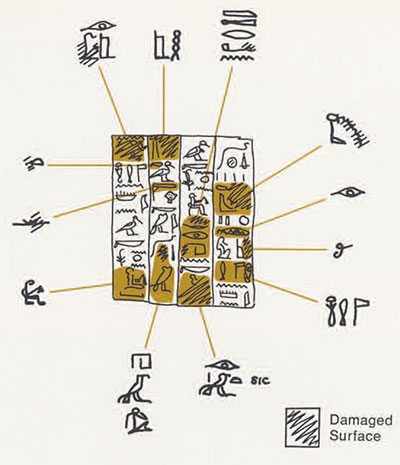

Inscriptions are incomplete and frequently end abruptly, and fragments of limestone and plaster are found with tantalizing bits of text on them. What remains is obscured by a layer of thick, dark smoke, deposited there from cooking fires when the tombs were inhabited. Thus, upon preliminary examination, the site appears largely in ruins; and, in fact, the tombs are generally poorly preserved. One might wonder why this work is being pursued. The answer lies in the fact that in spite of the difficulty of getting at it, considerable important information remains to come out of these tombs; and precisely because of the difficulties, it is inaccessible to casual observation and must be approached through thorough and systematic investigation. That is the work which has now been undertaken by the present project.

After making this brief survey, it was necessary to plan the details of the approach to the work. The entire site was inspected, and every accessible tomb in the concession entered and examined. Because of the various dangers confronting opened tombs, it is standard practice for excavators and the Antiquities Service to take certain steps to promote their protection and preservation. Chief among these measures is the closing of entrances, to prevent unauthorized entry. Most satisfactory is the installation of locked metal gates across the tombs, which are also provided with screens to keep out bats, birds, and other animals. In some cases, however, the tombs are in such poor condition, or in such an isolated location, that maintenance and inspection are difficult. These it is sometimes necessary simply to rebury, when they have been recorded, or to block up with stone and concrete. Others are blocked up for lack of funds to install proper metal gates. So not all the tombs are open to inspection.

With the information thus available, Professor Cerny and I discussed the project at Luxor, and then I journeyed to Abydos, where David O’Connor was working (cf. Expedition, vol. 10, no. 1, Fall 1967), to draw up with him a specific proposal for the commencement of the work. From among the accessible tombs we selected three which constitute a meaningful group—numbers 35, 157, and 283. These, belonging to the three High Priests of Amun, would lend themselves conveniently to publication in a single volume.

It is hoped thus to make it possible to undertake the publication of results while field work for the rest of the project is still in progress.

This proposal was outlined in an application to the Director General of the Department of Antiquities, Dr. Gamal Mukhtar. Permission was requested to copy in these tombs, and to clear tomb 157, in which up to a meter of debris on the floor conceals the ends of the lines of inscription. In addition, permission was sought to begin the preparation for work in a second group of tombs, numbers 156, 282, 289, and 300, belonging to the two Viceroys and the two governors of the south lands. Since 289 and 300 are now completely inaccessible—their entrances being entirely concreted shut, so that even the local watchman has forgotten the exact location of 289—it was proposed to demolish their blockings and replace them with metal gates.

This application was submitted to the full Committee of the Antiquities Service for approval, which was granted. Even while the application was being considered, however, temporary permission was secured for the commencement of the work of copying in the designated tombs. We of the expedition wish here to acknowledge the continued cooperation and assistance of Dr. Mukhtar, and of his staff in Cairo and at Luxor, throughout the season.

Since tomb 157 requires clearance and 283 is in a poor state of preservation, work was begun immediately in number 35, Bekenkhons. The first stage of the work consists of collating the copies of the inscriptions as made by David Greenlees, a member of the excavation of 1921-23. This is done by means of collation sheets. These present a portion of the original copy of the text, which is then to be corrected in the margins by a comparison with the text as it appears on the wall itself.

The daily routine of the work, once established, varied little from day to day—except when I occasionally abandoned the schedule in order to visit the Egyptologists at work on nearby sites, or adjusting it in order to show visiting Egyptologists around our site.

Up at 6:30 for breakfast at the Luxor Hotel, which served as expedition headquarters, I proceeded to the landing to take a ferry across the Nile, amid conversation with friendly locals and queries from curious tourists. I had originally paid the tourist price for this ride, but because I was working there and crossing daily, later convinced the manager that I was to be counted as a local in assessing my fare. It is surprisingly chilly on the river early in the morning, and a University of Pennsylvania sweatshirt comprised a regular part of my dress.

On the west bank I drank tea and chatted with the local guides and taxi drivers while waiting for my own driver. Again it had been necessary to reach an agreement with him on price, on the basis of steady employment, to avoid paying the tourist rate. This man, as I learned later, is an Abd er-Rasoul of Gurna, a member of the family famous for having located the cache of royal mummies discovered in 1881 at Deir el-Bahri. He owns his own car, and is very proud of it; and may often be seen with his head under the hood, making some adjustment or fixing the horn, which constantly troubles him. One day, just as I had gotten out to visit Deir el-Bahri and he was driving away, the steering linkage broke, and before he was able to get the car under control, it had hit a large boulder and overturned. Fortunately, neither he nor his young son was injured. The local wrecking crew came to lever the car into an upright position, removed it, and it was repaired and working again in only a few days’ time.

I had also hired the driver’s son as general assistant on the site and mirror-boy. The tombs are lighted with meter-square mirrors, one outside to reflect the sun onto a second inside, which directs the light to the particular portion of the wall we wish to see. Both must be moved to catch the sun as it crosses the sky, so that proper adjustment is maintained and the light can be held in one place for as long as necessary. This was the boy’s main job. The mirrors are custom-made and expensive, and also rather heavy. Unfortunately, one day he let one slip, and it fell and broke. So next season the expedition will have a mirror-man. Another disadvantage to using mirrors is that work is difficult on cloudy or hazy days.

Each morning we drove together from the river to the Inspector’s house to get the keys for the tombs, and then on to the village, where we were met by our one-eyed ladder-man, who conducted us up through the houses, along a path specially selected to avoid the most possible dogs, to the watchman waiting at the site. We have ladders of six and nine feet, to permit close examination of the upper reaches of the texts.

I encountered remarkably few language difficulties, one of the most striking examples being when I confused two newly-learned and similar Arabic words, and intending to determine in which direction south lay (gibil), I asked where was the gibna (“cheese”—much to the watchman’s surprise and amusement. At lunchtime I took the opportunity to explore the environs of the site, and following the afternoon’s work sometimes drank tea in village houses while waiting for the driver to return.

Once again at the hotel, I showered and changed, then made my way along the Nile to the Oriental Institute’s Chicago House. The Director, Dr. Charles F. Nims, had given me access to the excellent library facilities there. I wish here to thank Dr. Nims and the staff of Chicago House for all the kindnesses afforded me during my stay at Luxor. Some of the villagers thought I was affiliated with Chicago House, which at Luxor is simply called “Chicago.” I told them that I was from Pennsylvania, but that in America I had studied at Chicago. They were amazed to discover that there is a Chicago in America too! The inhabitants of Dra Abu el-Naga seemed not to have heard of Pennsylvania, but when I mentioned Fisher, they remembered his name, and knew where the ruins of his excavation house are.

After studying at the library, I boarded the Documentation Center’s boat to join Professor and Mrs. Cerny for tea with the Center’s staff, as the guest of Dr. Hassan el-Ashiri, Field Director of the Center’s work at Luxor. Afterwards I returned to the hotel, where I customarily had dinner with Mr. and Mrs. Ray Smith and members of the staff of the Museum’s Akhnaten Temple Project, who roomed at the same hotel when their work brought them to Luxor (cf. Expedition, vol. 10, no. 1, Fall 1967). It was then also and immediately after dinner that I talked as well to some others of the many professionals doing Egyptological work at Thebes. Then came the final preparations for the following day’s work, and early bed.

Although this was a season preliminary to full-scale operations, we have nonetheless advanced significantly toward the successful realization of some of the ultimate aims of the project. Already we have encountered among the inscriptions so far examined titles of Bekenkhons not previously attributable to him, and the names of some of his family. This evidence is useful in identifying his other monuments and reconstructing his career. But the bulk of the texts collated up to now have been identified tentatively as being from the funerary rituals known as the “Opening of the Mouth,” scenes 1-25. This text is known from approximately ninety sources, of varying extent and reliability. The differences in these versions are important for establishing the original text, as well as for interpreting its significance.

At the end of the season, on April 15, our supplies and equipment were stored at Luxor, ready for future work, in facilities generously made available at Chicago House by Dr. Nims and at the German House by Dr. Dieter Arnold, Director of the German Archaeological Institute’s wok in Egypt. We also moved, with the help of the local boys, more than thirteen hundred fragments of inscribed stone and painted mud-plaster from open areas on the site to storage in relative safety behind the locked iron gates of the tombs. Finally, just before closing down the camp, I gave the expedition’s large flashlight to the watchman to aid him in guarding these fragments and the rest of the site.

[Mr. Bell left for Thebes in January to begin the work of the second season. —Editor]