The Shoshone, like many other nomadic peoples of the Plains and the Rockies, are scarcely known to archaeology. Their ways of life left scant traces on our landscape. When we do find their scattered archaeological record in many areas, it becomes apparent that they had been newcomers with little relationship to older complexes. The Ute and Shoshone hunted over many parts of Colorado, Utah, and Nevada that had earlier supported sedentary farming peoples of the Promontory, Fremont, and other non-nomadic cultures. The sedentary peoples withdrew to the south about A.D. 1300, probably to become the Navaho, and to be replaced by Shoshoneans. The Shoshone, guardians of the Rockies, are among the most elusive folk in American Indian prehistory.

We selected the Bridger Basin in southwestern Wyoming to survey and search out traces of the Shoshone for three reasons. Our museum collections include stone tools and flint-tipped arrows collected there from Shoshone a century ago, when the Indians were still carrying on their Stone Age arts. We wanted to find the same tool types in the ground. The Bridger is so high and cold that horticulture is impossible today. Thus we felt that sedentary cultures of earlier times had never occupied the area, and that it lay within the original territory of the Shoshone. Finally, no one had studied the archaeology of this basin, so that it stood out as a completely unknown region closely tied to Shoshone history.

We spent two weeks in the Bridger in 1967, scouting out the landscape, meeting local collectors, making collections from twenty sites, and defining problems in the field. We found a semiarid land eaten up by sheep and blown away by the wind, where excavatable sites scarcely survived. We returned for the summer of 1968 to test our ideas by further site survey methods and to collect better samples. We are now working at description of late prehistoric stages in Shoshone and Ute archaeology and at problems of earlier culture stages in the Basin.

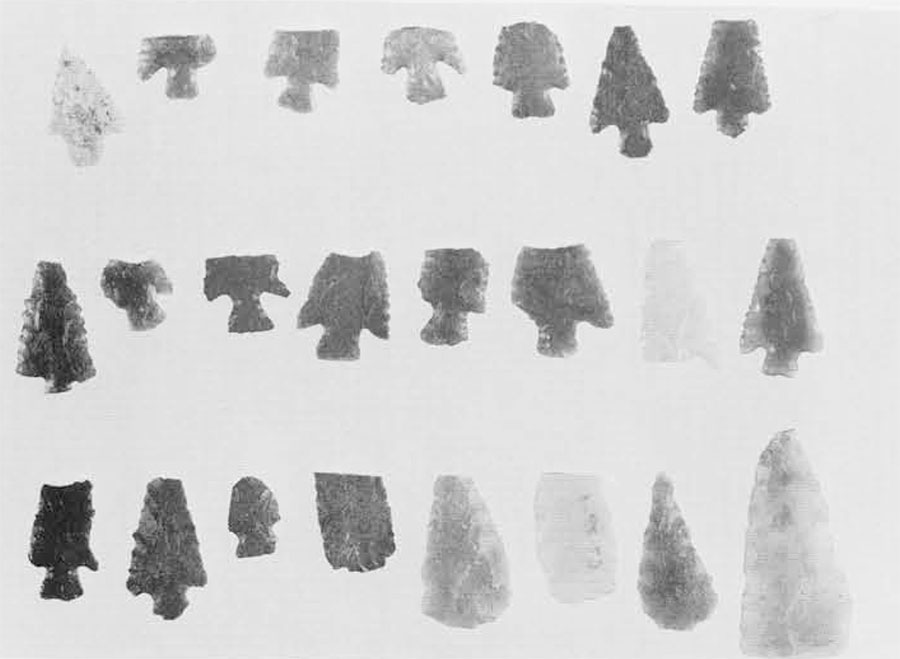

We stressed late sites in our sampling, attempting to get an adequate series of tiny arrowpoints, of the roughouts for them, and of associated tools and lithic debris. We also made latex molds of critical specimens from key sites in local collections. We now have samples adequate to the definition of three technologies of very late date, one of them Shoshone and the other two probably Ute. We also worked back into time, building a chronology for earlier industries. We found no traces of the pottery or other tools of the sedentary farming cultures, but we have good samples from the nomadic occupations.

Earlier students of Wyoming archaeology have focused their attention upon problems of early man in the area. We felt that such concentration was one-sided, and that the greatest gaps in knowledge pertained to recent times. We did little survey on the highlands around the Basin where early material might be expected, aiming our efforts at the least-known and most recent periods. We partially failed in this effort; we could not avoid finding industries which have been described as Lower Paleolithic complexes. We found them upon very recent land forms and as part of post-Pleistocene soils. By attacking problems of the recent past we had stumbled upon new information which suggests practically no human occupation in the Basin more than nine thousand years ago.

No Clovis (eleven to twelve thousand years ago) nor Folsom (ten to eleven thousand years ago) tools of any type have been found within or near the Bridger. Tools of the Eden Valley Complex or Cody Complex are scant, and are found only on the high rims of the Basin on Pleistocene terraces by stream heads within the Basin. Our studies of the landscape and of its glacial geology suggest that the area was not fit for human occupation during Paleo-Indian times, was subject to great diurnal floods from the mountain glaciers of the Uinta Range. Man can scarcely live upon a glacial outwash plain. The Bridger, like much of the Interior Basin to the west, appears to have been a frequently flooded wasteland during glacial times, its buttes standing as islands above the flood.

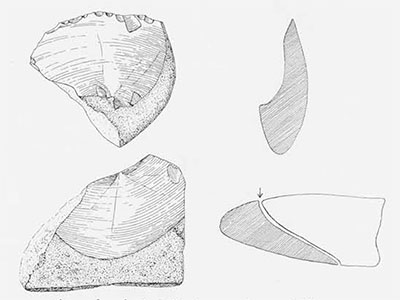

The Black’s Fork Culture, defined by Renaud in the 1930’s from sites farther down the valley, is thus a controversial complex. Great antiquity has been claimed for it. It consists of crude massive tools of quartzite and flint, notable for their primitive character and large size. They have been compared with the most ancient stone tools from Eurasia and Africa.

As a result of our survey data, we can now divide the Black’s Fork Culture into at least three different technologies of different ages. The most recent of them, in Clactonian style, is part of the material culture of the Shoshone which persisted into the last century. The most ancient Black’s Fork types which we found are less than eight thousand years old on geological evidence.

The earliest material in the area is anything but crude. It is identical with specimens from the nine thousand year old Finley Site in the Eden Valley north of the city of Green River, Wyoming, which was excavated by Linton Satterthwaite for the University Museum on earlier expeditions.

Catalouging and analysis, drawing and graphing of our half-ton sample are in process. Defining and dating the various technologies of the Bridger Basin is the immediate objective. Back of that lies a still-undefined story of the evolution of the culture of a nomadic tribe, the Shoshone.