Archaeologists may have done their work just a little too well. They have sung the praises of ancient man so long and so well that the message ultimately sank in. So it is not wholly surprising that the public and the museums now want a piece of the action. Their demand and buying power have created a bull market for ancient art and a flourishing worldwide traffic in antiquities, much of it clandestine. To supply this market looters are rapidly destroying much of the evidence from which archaeologists hope to piece together a record of the human past.

No part of the world has been immune from the ravages of the tomb robbers. In Peru, Italy, Turkey, Africa, Southeast Asia, even deep underwater on the floor of the Mediterranean and Caribbean Seas, amateur and professional looters are systematically hunting the pots, vases, sculpture, figurines and other objects once considered little more than “specimens” of interest mainly to scholars in musty attics.

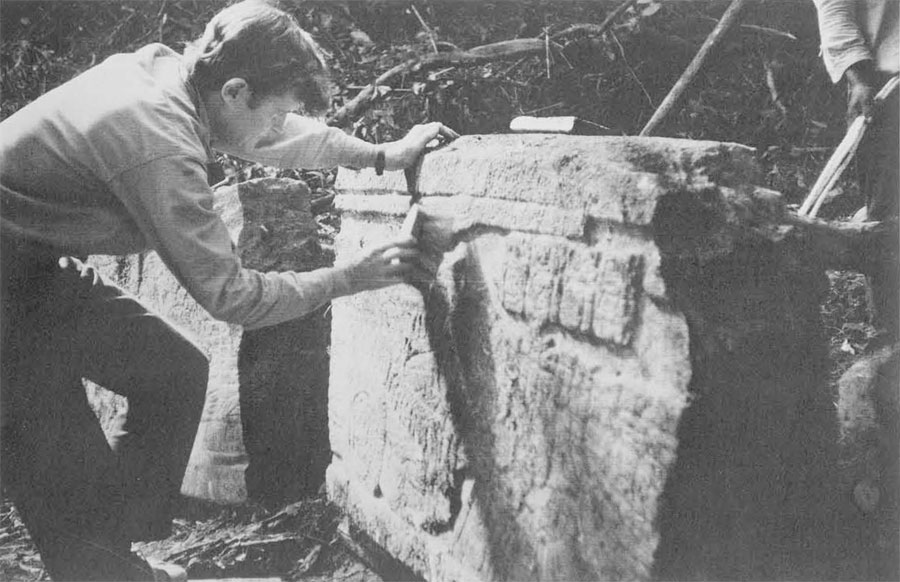

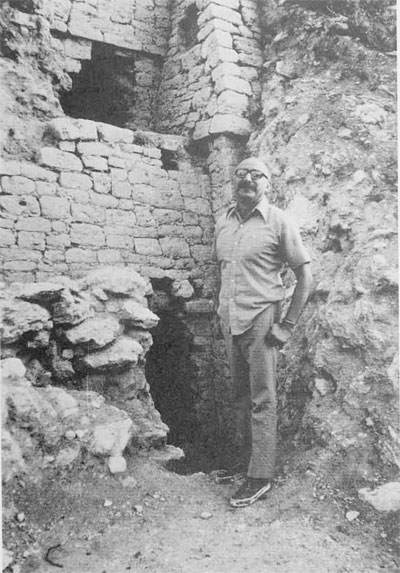

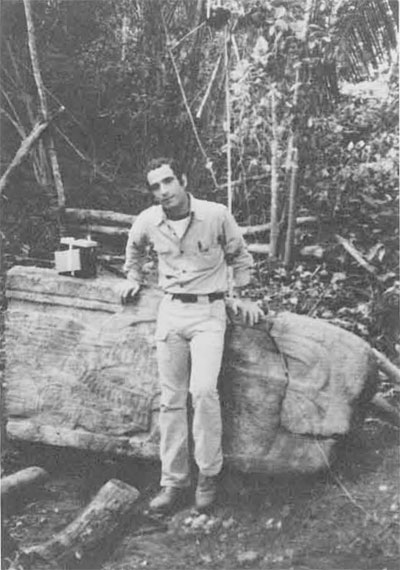

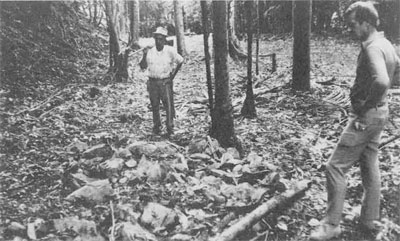

Perhaps the worst depredations are to be found closer to home, in Mexico and Guatemala, where thieves have swept through the ruins of the great Maya and other pre-Columbian Indian civilizations. What the thieves have not yet taken is rapidly being paved over by real estate developers and road builders. Armed with chain saws and sledgehammers, the looters have wrought tremendous damage to extract mutilated objects that are to be found today on pedestals in some of the most respected art museums in the United States and Europe. Probably few in the Sunday museum throngs are aware that the objects may have been “exported” under a truckload of bananas or under the imprimatur of phony exit permits.

All of this has been amply documented in both the lay and professional press, most recently by this reporter during a five-week visit to Central America on assignment for The New York Times. It would perhaps not be fruitful to attempt in this brief article to recite again the long litany of destruction carried out in the name of art. More to the point is the knotty question of what to do about the problem.

There are no easy answers, for the situation is a complex one with few clear-cut villians and heroes—even the archaeologists are not without fault. The solution is likely to require international cooperation, always elusive, and the resolution of many conflicting and possibly irreconcilable forces—the legitimate needs of both scholars and museum curators, the inflationary economy, economic realities in poorer countries, and official corruption.

Of course, the destruction and looting of antiquities is not entirely new. What is new is the dimensions the depredations have reached in the last few years as prices for “primitive art” have soared. This pattern has attracted many a collector who was perhaps not so much interested in the fine points of Olmec sculpture as in the fact that prices were likely to double or triple in short order. At the same time, many affluent new museums in the United States and Europe have fueled the spiralling market attempting to establish their reputations with major acquisitions.

In the view of many specialists, mostly university-based “digging” archaeologists, the solution to the looting problem is to cut off this market. Therefore a number of museums have adopted strict new policies forbidding the acquisition or display of any object whose pedigree does not establish unequivocally that it was removed legally from its country of origin. Such policies have been embraced by the University Museum at Pennsylvania, all Harvard University museums, the Field Museum in Chicago, the Smithsonian Institution, and a handful of smaller institutions.

But none of the major general museums have followed suit, and this fact underscores the gulf that has opened between the research scholars and the museum curators, two groups that would seem to have a commonality of interests. Archaeology was once in large part concerned with filling museum shelves back home and many of the early digs were probably little more than pillaging. In recent decades, of course, the profession has become much more sophisticated and the emphasis is now on “problem solving,“ on reconstructing the social, economic and political forces that prevailed in ancient times. Therefore, the archaeologist tends to view relics as clues to a puzzle and not primarily as art objects. Once a piece is removed from its original setting, where its relationship to surrounding objects can be scrutinized, it loses almost all scientific value. Of course, the looted objects that pass through the New York and Paris galleries are without provenance. Without question, the looting is damaging archaeological work, and tragically the damage is probably the worst in areas, such as the Maya region, that remain largely mysterious.

Although many general museums are taking a second look at their acquisition policies—as a result of much adverse publicity and new legislation—the museum curator is basically committed to collecting and displaying art. As such they have come into conflict with archaeology, which many of them believe has assumed a selfish self-serving stance that would deny the public access to great art. When a museum does not have art, it dies, it becomes stagnant,” says Gilett Griffin, curator of pre-Columbian art at the Princeton Art Museum.

“Many of these museums that are raising all this hell have enormous collections almost all of which is looted,”

said another curator, referring to the pre-Columbian objects owned by the Peabody Museum at Harvard and the University Museum. “They do not want the have nots to have any.” The Peabody and University Museum collections were gathered many years ago with permission of the governments involved.

Another cynic is Prof. Michael Coe of Yale, one of a minority of professional archaeologists who criticizes his own profession as hyprocritical, saying that much of the worst destruction is done by archaeologists themselves. “Many archaeological excavations are never written up—that is pure destruction, even worse than the looters do,” he says. “It’s a lot more fun to dig than to write—the glamor is all in the expeditions.”

Many curators and art dealers argue that the heritage of ancient culture is often better protected in the well-maintained museums of Europe and the United States than in the countries of origin. Samuel Sachs, acting director of the Minneapolis Institute of Art, said his museum has been considering the return of a Maya stela it bought a few years ago, only to discover later that the object had been stolen from the remote Guatemalan site of Piedras Negras, which was once excavated by Pennsylvania. “But I don’t know if Guatemala can take care of it,” he says. “I am not sure we would be doing Guatemalan heritage any good at all—their heritage is better protected in European and American museums.”

While such assertions are not without self-serving purposes, there is perhaps something to them. Travels in Central America suggest a widespread lack of concern for the magnificent heritage left by the ancient Indians. Given the desperate economic and social problems afflicting Latin America, this is perhaps not surprising, but the impact on the past is nonetheless devastating. Roads throughout Yucatan, for example, are paved with the rubble of ancient pyramids, fed into rock-crushing machines because it was cheaper than buying gravel. At one Mexican site, vandals recently smashed a magnificent stucco mask, apparently out of spite for the caretaker of the ruins because he has steady work. One art dealer says he has witnessed chicle, gatherers and lumbermen using stunning murals for rifle target practice. With some 11,000 archaeological sites in Mexico alone, it would clearly take many lifetimes for trained archaeologists to excavate them all properly. By that time, some argue, the ravages of the jungle and the developers will have destroyed much of what is left.

In Guatemala several sites considered national treasures, such as the ancient site of Kaminaljuyu, have been largely paved over by real estate developers. And in both countries, important government officials have occasionally been implicated in the illicit traffic. Most recently, a Guatemalan customs administrator was named as the head of a smuggling ring.

In an effort to stem the rising tide of illegal antiquities, the governments of Mexico and Guatemala have passed stringent laws forbidding the export of all ancient objects. But many believe the laws, which make no provision for the sale even of minor or duplicate material, are only fueling the black market. One Mexican official, who disagrees with the Government policy, claims that since the crackdown on dealing within Mexico began, the traffic has simply shifted to New York, Los Angeles and Paris. “It is obvious the results have not been very happy,” he asserts. “They have more antiquities from Mexico in Los Angeles and Paris than ever before. It means they are still looting.”

American art dealers and museum curators trade dark stories of intrigue and duplicity on the part of Latin American police and government officials. One American dealer, who has been arrested a number of times on charges of illegal trading in Mexico, reports that he has seen objects confiscated from him by Mexican police turn up later on the New York art market. And an American collector who gave several pieces to the fabulous new National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City when it opened a few years ago now says that some of the pieces have inexplicably disappeared from the collection. In the past, a number of Mexican museum officials have been arrested on charges of selling objects from their museums.

Moreover, the digging of artifacts constitutes no small industry in some underdeveloped countries. Prof. Dwight B. Heath, an anthropologist at Brown University, has studied the “huaquerismo” phenomenon in the tiny country of Costa Rica. He estimates that about 4,400 people, or one per cent of the labor force, derive more than half their income from “commercial archaeology,”as he calls it. Their product, he states, amounts to half a million dollar industry and since most objects are exported it also represents an important source of foreign exchange for Costa Rica. Prof. Heath concludes:

“Although I am by no means an apologist for the unfortunate depredations wrought by looting the past, I submit that we must recognize it as serving important economic and other functions for many people in areas of the world where opportunities are sharply limited. This is one reason why it is difficult to assign culpability to those who actually do the damage, with shovel in hand. This is also one reason why restrictions can probably be more effectively imposed among consumers than among producers.”

Such restrictions on “consumers“ are being raised. A recently enacted American law prohibiting the import of larger architectural and sculptural objects from pre-Columbian areas appears to have blocked the flow of such objects to the United States at least. If ratified, a new UNESCO convention on art traffic may also have some effect. But as so often happens with black market commodities, when one outlet is blocked, another is opened. Already there are indications that the traffic is shifting to Europe and Japan.

Many American museum curators fear that if they are cut off, the best objects will simply find their way to other countries and the American public will be deprived. Meanwhile a sometimes acrimonious debate has broken out among scholars over how to approach the problem. Many believe that professional anthropologists and art historians must end the old practice of authenticating and evaluating objects for dealers and collectors. “The size, destructiveness, and the money now involved in what used to be a relatively innocuous trade have turned the scholar, who would only authenticate an object, into an accomplice,“ writes Clemency Goggins, an art historian who has been in the forefront of the crusade against the looting.

But others resent this suggestion. One of the scholars who has maintained cordial relations with the dealers is Prof. Coe of Yale. While he deplores the depredations, he argues that scholars should come to grips with the reality of the situation. As long as the trade continues, he says, it is important to keep track of it lest important pieces go underground and be lost totally to scholarship. “According to the archaeologists,” he says, “we should not look even at the Rosetta stone.” And Prof. Coe expresses some sympathy for the general museums and their efforts to ease legitimate exchanges. “We need better laws. The Metropolitan cannot show just Manhattan Indian primitive art objects.”

These then are some of the complicated ramifications of the problem. They are spelled out not to justify or defend the deplorable depredations visited on the past, but to suggest that the situation is far more complex and difficult than some have assumed.